Laid on top of an operating table, a mermaid bids farewell to her aquatic body, and does so singing. Her song, however, has less to do with the actual act of losing her tail and becoming human than with the aftermath of her choice (“I’ll be wheeled down the aisle with my surgical gown”) and depression setting in (“I cheer myself up with bitter chocolate”), until her high-pitched vocals are gradually overpowered by the buzzing of a medical saw and the mellifluous voice breaks, lost forever. A mermaid-to-human metamorphosis turns Agnieszka Smoczyńska’s horror-musical debut feature, The Lure (2015), into a body-specific rendition of Hans Christian Andersen’s infamous fairytale about a siren who gave up speech in order to attain human legs, and with them, she hopes, human love. The film’s significance within the history of film musicals hinges upon the mermaid figure, which exemplifies the philosophical stake of (silenced) female voices. Two key musical characteristics of The Lure are its distinctive use of staged performances and its opposition between singing and aphonia.

In the film, two cannibal mermaid sisters—Silver (Marta Mazurek) and Golden (Michalina Olszańska)—arrive in Warsaw, wagging their tails down the stream of the Vistula River. Temporarily transformed into female humans, they set foot on the shore to find a human world (specifically that of Poland’s 1980s communist regime), which they know nothing about. Foreigners as they are, the mermaids provide any viewer not necessarily acquainted with the particularities of Polish history a point of entry. And the film world, as they experience it, is bright, glittery, and dissipated.

The desire to metaphorize a unique personal, but no less political, past is what drove Smoczyńska to make a mermaid film. Born in 1972, the filmmaker excavated her own early teen memories of when her mother was a performer in a cabaret-style restaurant, which proffered a Janus-faced version of reality. “The world was colourful on stage, but behind the scenes everything looked different, cooler, more painful”Smoczyńska reflects on the political retelling of the past only in Polish interviews. See, for instance, ‘Agnieszka Smoczyńska: Amerykanie zakochali się w “Córkach dancingu'”‘, dziennik.pl (December 25, 2015), , she reminisces while also admitting to a certain desire to document a leaving world. The director also worked closely with the pop music duo Ballady i Romanse—comprising of sisters Barbara and Zuzanna Wrońska—and melded their own coming-of-age story with her memories, as all three of them grew up in similar circumstances. Making a cameo in the last scene, the Wrońska sisters also composed the film’s music, synth-pop renditions of older Polish tunes intertwined with original absurdist but nonetheless catchy songs. By “turning” the sisters into mermaid characters, the filmmaker and her screenwriter Robert Bolesto retell a certain private history through which the contested and fetishized figure of the marine female creature manifests the anxieties accompanying nostalgia—for fairy tales, for the communist disco era, for an artificially constructed world of a horror-musical where the cannibal sirens expose misdemeanours, labour politics, and intrigues.

According to Raymond Knapp, film musicals often present the opportunity for the song-and-dance performances to weave their artificiality (as planned, choreographed, rehearsed labour-intensive processes, they are bound to hide the aforementioned labour in light of their entertainment purpose) into a more naturalistic setting than stages can provide. As such, film musicals enable an increased level of awareness of the performers as performers, not only as characters.Raymond Knapp, The American Musical and the Performance of Personal Identity (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2009) 6. Even though The Lure capitalises on the mermaid figures as enchanting singers, the vocal and dance performance of Mazurek and Olszańska holds the camera’s attentive eye. Both are often framed as moving bodies (and tails), repeatedly fragmented by close-ups of singing heads or body parts, the gaze switching from objectifying to empowering in its subversiveness. However, Knapp’s argument relies on film musicals’ foregrounding the performers in musical numbers, which would then render the background itself irrelevant (be it a stage or a room backstage). The Lure combines the prolonged visual excitement of the musical acts with a constant reminder, through its art direction, of the film’s specific national context.

If in other film genres such an emphasised artificiality is used to achieve a Brechtian Verfremdungseffekt, in musicals (both Hollywood ones and the New European musical discussed here), emotional engagement is key, so the sense of (sought) belonging becomes vital. As an alternative, magical realist version of the past, The Lure is plainly nostalgic. Secondly, as a geopolitical product, the film is ostalgic—“Ostalgie” being the term used to describe an ambivalent relation to Eastern Europe’s communist/socialist history. Thirdly, as a musical, The Lure brings forth the nostalgic qualities associated with the Hollywood musical which, according to Richard Dyer, have more to do with feeling utopia rather than a certain utopian order of things.Richard Dyer, ‘Entertainment and Utopia’, Movie 24 (Spring 1977): 2-13. The film never truly severs the link between the “then” and “now” but only mediates it through nostalgic qualities (classical film style), characters (mythical mermaids), and setting (reconstructions of 1980s Warsaw). Similar trends resonate in the choice of diegetic music, a mixture of cover songs and original pieces, both influenced by Polish dance music, American disco, and of course, the region-specific urban folk genre “disco polo”.

Polish Mermaids

The Lure does not present its audience with a concrete time frame of events but the film’s aesthetics—props, costumes, locations—are telling of a 1980s Poland. The main setting of the film is a so-called “dancing restaurant” of the Soviet era. Typical establishments in all USSR satellite states, with their dining menu and entertainment, they resembled the American and UK supper clubs, combining underground character with urban prestige. Musical numbers are acted on stage and behind the scenes (in back rooms and canteens), which positions The Lure within the longstanding tradition of backstage Hollywood musicals from Lloyd Bacon’s 42nd Street (1933) to Steven Antin’s pop-star studded Burlesque (2010). But geopolitical specificity also comes into play: the liminal space of such restaurants pre-1989 is characterised by an obsession with Western culture—defiant covers, copies, interpretations, but never a faithful duplicate of a brand or an artefact. The distance contained within these copying mechanisms, also places the conventions of the musical at a remove, mainly the ones blending worlds of song with those of reason.

A curious spin on the siren myth takes the gift of song and places it within the economy of immigrant exploitation, when Silver and Golden become an integral part of the restaurant’s regular band. On the one hand, their angelic, enchanting voices (those of sirens, famous for luring sailors to their death) captivate the audience, but on the other, their corporeal transformation from legs to tail is the main attraction. Their metamorphosis is repeatedly staged as a show for profit and such a scheme is fairly reminiscent of early freakshows and the concomitant exploitative mechanisms of commodifying the disabled body as spectacle. However, it’s the mermaids’ hybridity that causes double trouble—their subsequent exoticisation and the fear of their monstrous side, regardless of the attempt to repress it by economic subjugation.

In spite of their sexualised appeal, the sisters are also known as vampiric cannibals: fangs, bloodthirst, and all. As a genre hybrid between horror and musical, drama and comedy, The Lure shows non-normative bodies, not-quite-human creatures, and female voices as victims of rigid, patriarchal structures ready to fetishize and assimilate them.

Who Sings?

Youthfulness, beckoning promises of eternal love, more often sung than whispered, and a fetishized hybrid corporeality make up the popular on-screen mermaid. Her physical presence is exposed as simultaneously attractive and repulsive (which many other mermaid films have done before). It’s impossible to define a mermaid musical without the glaring presence of Disney’s 1989 The Little Mermaid, with its infamous tunes written by Alan Menken that took home two Academy Awards, Best Original Score and Best Original Song (‘Under the Sea’). In opposition to Disney’s notoriously sanitised version of Hans Christian Andersen’s fairy tale, which omits the physical pain accompanying the protagonist’s becoming human, The Lure highlights not only the originary statelessness of mermaid figures, but also the agonizing loss of human voice in a setting that relies on acoustic presence.

Sirens have long been related to speech and song, and this relation was later transferred onto mermaids. In her monograph For More than One Voice, Italian philosopher Adriana Cavarero links sound and songs with a bodily presence even before articulated, well-formed words, which become secondary and more ephemeral. “Woman sings, man thinks”, she writes.Adriana Cavarero, For More Than One Voice: Toward a Philosophy of Vocal Expression (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2005) 6.

It seems more than suitable for The Lure’s sexual politics that most of the songs (especially those performed on stage) are reserved for women. Men are often banished to backing vocals and remain, whether speaking or singing, barely audible, especially when in a group. The only two men who get to form a duet are Silver’s love interest, Mietek, who also symbolically betrays her by singing their song with another woman, and Triton, the merman who’s sacrificed his non-human tail and horns to stay on land and lead a punk band. Indeed, male voices are never granted songs of their own, and the delineation of male/female spheres only furthers the pre-existing gender dynamics in a diegesis which has already done away with cinematic realism but retained the real world’s flawed order.

Such a gender delineation confirms Cavarero’s arguments on the bodily function of voices. Sonic vibrations, according to her, constitute one’s own individual presence, even more so in a way that is not necessarily bound by rationalised articulation. One’s voice, the equivalent of a lost or hidden valuable, is not an ineffable essence, but the elongated pleasure of continuously revealing oneself acoustically, not just eloquently. In Cavarero’s paradigm, the ethical significance lies with the phonic self-announcement, and in The Lure, both song and inarticulate growls mark the presence of sirens. After Silver becomes mute (and also when the sisters are hunting their male victims), the mermaid’s vocal presence is confined to snarls and screeches. Whether taking the form of a lyrical or nonhuman self-announcement, the vocal aspects of identity are brought to the fore. As the pleasure of sung self-announcement chimes with the entertainment value of musicals, the blood-curdling behaviour of the cannibal mermaids brings us into the realm of the horror film.

Loss of Voice

Following the Andersen tale, The Lure finishes on a tragic note, when Silver’s object of affection rejects her after she performs a most painful transformation to swap her tail for legs at the cost of her voice. Since the metamorphosis, as shown in the film, resembles a cosmetic or even transplant procedure, it places emphasis on physical suffering and thus draws further attention to the female economy of loss that is embedded in mermaid legends and more broadly in voicelessness throughout patriarchal history.

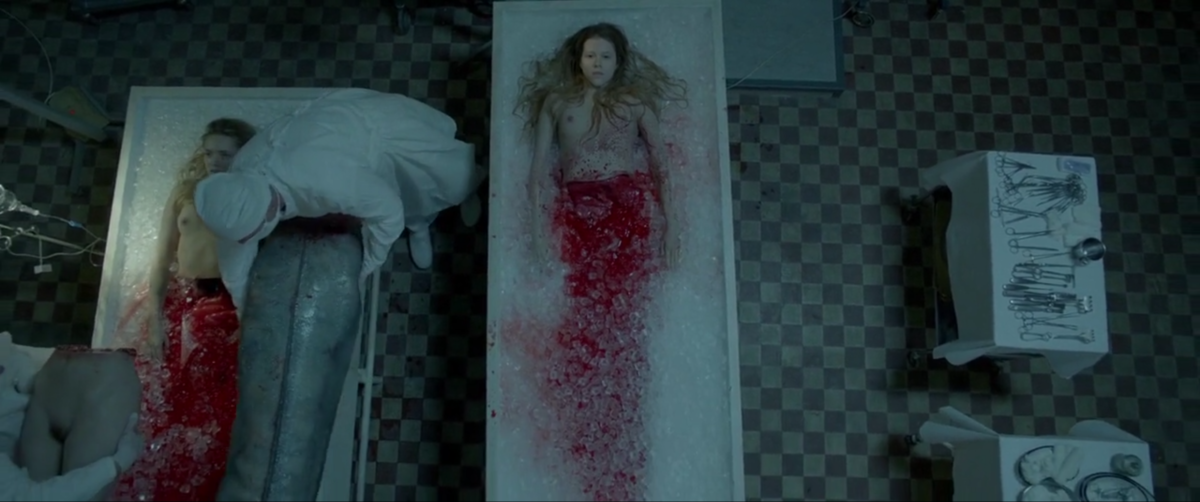

While the fairy tale relegates the pain to after the transformation, where each stride is equally painful but invisible to everyone else, The Lure thrusts its viewers into awareness of a transformation that is not only pertinent to the surface but cuts to the bone. The camera gradually descends from its bird’s eye view, then slowly twirls, freeing the composition of its stillness, rearranging the space in order to fit the mermaid’s upper body in the frame. From the lower right corner, a pair of bloody gloves emerges with an autopsy saw in hand. Monotonous and even, the mechanical sound of the surgical saw serves as an even tone upon which Silver weaves her higher notes over the minor keys of the piano. The camera zooms in, framing the saw even more tightly, ready to cut the mermaid’s body in half, while also halving the shot itself. Even though Silver is conscious throughout the procedure, her voice weakens as the surgeon’s steady hand tears the flesh. The most painful place to strike is at the very visible boundary between fish and woman, where skin meets scales. We are left to ask ourselves, “Where does a body end?”

Silver loses her voice, but unlike in Andersen’s tale, where the voice is offered in payment, here it’s wiped out with the dissection of the tail. The film makes this apparent by silencing Silver’s song mid-sentence, while the words rolling sweetly off her tongue turn to a screeching noise, her mouth gaping open in disbelief, as the camera pulls back into a bird’s eye view medium shot. However, the shot composition and the camera movement are reminiscent of a more traditional way to establish distance, characteristic of the classical Hollywood musical and its backwards dolly. Instead of holding its female subject in a rather glorifying gaze, Jakub Kijowski’s camera makes the tissue damage visible, with blood stains all over Silver’s torso and a widening gap between her upper body and her fish tail. What follows is a procedural transplant (the swap of tail for legs) which is, at first, monitored up-high from a canted angle, and the floating camera creeps up slowly until an extreme close-up of the stitching process takes over the whole frame. Trading a magical legs-for-tail metamorphosis for a pseudo-scientific procedure, The Lure in fact rejects what should feel as an objective distance gained by both camera angles and the painful nature of the transformation itself.

The centrality of voice and its loss helps establish The Lure as a musical, and the film’s delving into horror tropes (cannibalism and monstrosity) in a way reconciles the mismatch between voice and body already evident in mermaid/siren mythology. Silver’s excruciating metamorphosis not only retains both the physical pain and loss of voice present in the Andersen tale, but also suggests that hybrid identity can be transposed over the film’s hybrid form. Ultimately, The Lure’s body politics might lead the viewer to consider the bodily dimensions of European politics.

Even as a surgically-produced hybrid, Silver, post-operation, is a product of reproduced trauma, rather than simply replicated upon another body. The act of stitching together not only a precise gender identity, but also a national one, brings a possibility for release, for transcending the trauma through transformation. Instead of a magic trick, concealing the process and revealing the unquestionable aftermath, the harsh surgical realism of the transformation itself gestures towards a new possibility for Eastern Europe and European cinema as a whole. Whereas the yearning for a newfound mobility after the fall of the Berlin wall has been traditionally represented by narratives of journeying, misplacement, and migration, The Lure proposes that an actual, homogenous alternative of mobility (which entails the lack of home) can be placed in hybridity, which is the lack of unified form. While Silver’s bodily transformation also aims at bipedal mobility, her own design and consent shape what her future body would look like, which, read allegorically, can expand the meanings of “mobility”, intricate to an understanding of what European identity has come to mean after 1989. While Silver’s choice to acquire human legs legitimates her status in the world of man, she loses the potential for a fluid identity—she can no longer alternate between tail in water and legs on land. Paradoxically, her claim at human mobility strips her of actual mobility between worlds—just as Andersen’s mermaid, Silver had the opportunity to experience both sea and land, embodying the possibility of Europeans to move freely between East and West after the fall of the Berlin Wall. Therefore, by denying this particular phantasma of mobility, The Lure signals that a quarter of a century after the events of ’89, this desire has finally lost its scintillating power.

The Lure, a mix of musical numbers and slasher horror scenes, exemplifies both the enchantment and the disenchantment of Eastern Europe with its own recent history. Smoczyńska’s film demarcates a pivotal moment when Europe, post-financial crisis and still feeling the tumultuous effects of the migrant crisis, looks back at its own communist trauma by means of fantasy and mythology. The pain of having to choose a single identity (mermaid or human), and the choice of legs (mobility) over voice (articulation) echoes the traumatic rift in the whole of Europe since the consecutive crises disrupted all promised ideals of a unified European entity. With its exemplary, singing cannibal mermaids, The Lure makes its audience reconsider any solid delineations between popular film and arthouse, between beautiful and grotesque, between human and animal, between angelic and monstrous, exposing such dichotomies (some of which a post-Enlightenment aesthetics was proudly built upon) as way too rigid and way too dysfunctional to survive in a New East. The permeability of boundaries speaks to the heart of the “newness” of this denomination where the fantastic properties of a communist past meet the free marketization that took hold after the fall of the Berlin Wall. The New East, fundamentally heterogenous and fragmented, therefore has no use for permanent mythological symbolism. The mermaid becomes human, no questions asked.