I really believe there are two types of artist. One kind celebrates beautiful things, and the other type reveals what is ugly and unpleasant in the world.

—Xie JinBerry, Michael. Speaking in Images: Interviews with Contemporary Chinese Filmmakers (2005), p. 46.

There might have been a day, probably in early 1957, when Jean-Luc Godard and Paul McCartney both sat down to watch The Girl Can’t Help It (Frank Tashlin, 1956). What is sure is that it impacted each of them: the filmmaker’s early work pilfers from its garish colors and the musician used a song from it as a bid to join a young John Lennon’s band. The two artists share an unwavering faith in the modern world and an impulse to, in Xie Jin’s words, celebrate its “beautiful things”. For McCartney, this is concentrated in the reproducible electric guitar lick, corporatized romance, and the transistor radio; for Godard, color film, large vehicles, and video recordings of old movies. Proof of faith is a willingness to criticize, which they share with Tashlin, a lover of the modern world disguised as a cynic. The Girl Can’t Help It features early rock and roll performances by the likes of Little Richard, Gene Vincent, and Eddie Cochran, framed by a narrative starring Tom Ewell, Jayne Mansfield, and Edmond O’Brien, and so is, by definition, a movie musical. The movie takes seriously a teen fad—rock and roll was predicted to pass imminently—and approaches it as a natural and exciting part of life, even a reason to participate in the world. Tashlin succeeds in the rare feat of making a musical—and a comedic one at that—which takes the world seriously and accepts it as it is.

Tashlin is not often considered a director of musicals, perhaps because his more common label of “satirist” can obscure the formal features of his work. He began his career directing Looney Tunes shorts, and their insistence on song stuck with him; nearly all of Tashlin’s live-action movies feature characters performing numbers, whether they fit into an overall structure (as in the mostly-traditional musical Rock-A-Bye Baby [1958]) or not (as in Will Success Spoil Rock Hunter? [1957], whose lead sings one song halfway through and never again). The singers’ voices are often grating, like Bob Hope’s in Son of Paleface (1952) or Jerry Lewis’s in his many films with the director. When no one sings, elaborate gags are choreographed to music, such as the hospital gurney ricocheting through the streets in The Disorderly Orderly (1964).

Musicality is just the stuff of life for Tashlin. The plot of The Girl Can’t Help It is ridiculous, a descendant of the hard-edged musicals of the 1930s, like Sing and Like It (1934). Jayne Mansfield stars as Jerri Jordan, unwilling subject of gangster “Fats” Murdock’s plot to turn her into a pop star and, thus, marriage material. Murdock (O’Brien) hires press agent Tom Miller (Ewell) for help, who finds out she can’t hit a note for her life and would rather be a housewife. After he parades her around various New York nightclubs, where most of the musical acts are featured, the two fall in love on the sly; a coda reveals they go on to have five children. Murdock ends up the unlikely star, scoring a hit with his prison blues ‘Rock Around the Rock Pile’. In the final scene, Murdock watches impotently from the television screen as his two pawns make love; an ascent to stardom is the punchline. Against this plot, the musical acts are breaths of real life—committed performances that engage with their physical world. It’s a testament to Tashlin’s absolute sincerity that this near-mess of jokes and social commentary would go on to inspire works as generous to the world as McCartney’s ‘All My Loving’ and Godard’s Pierrot le fou.

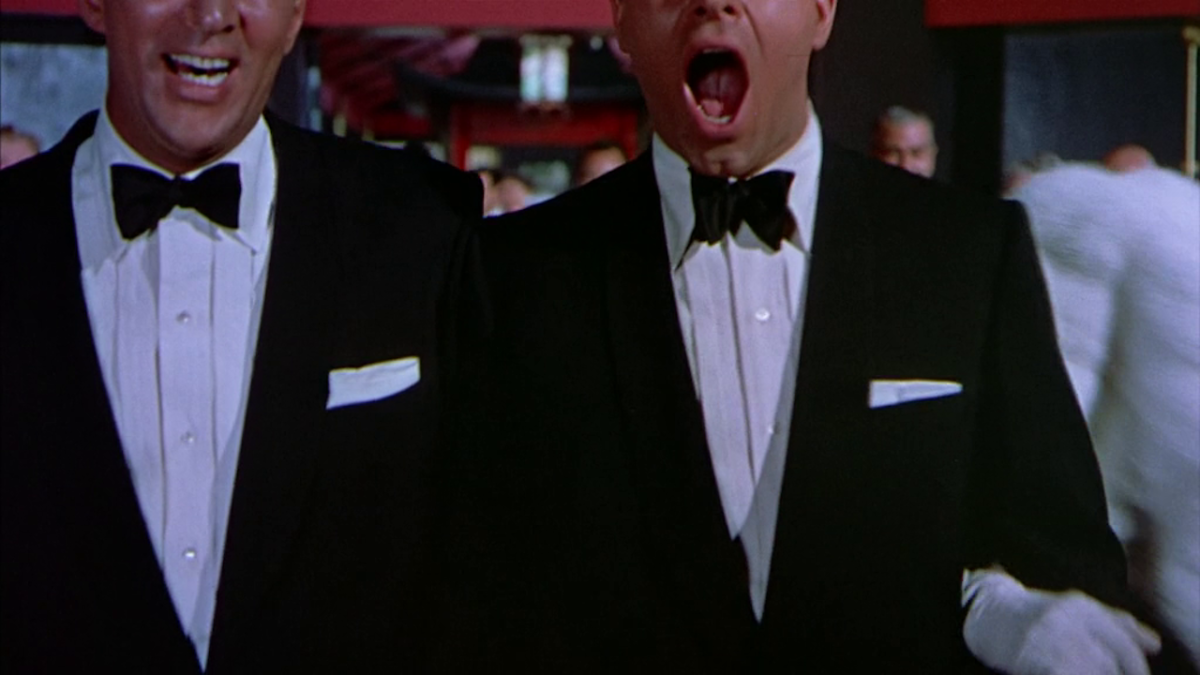

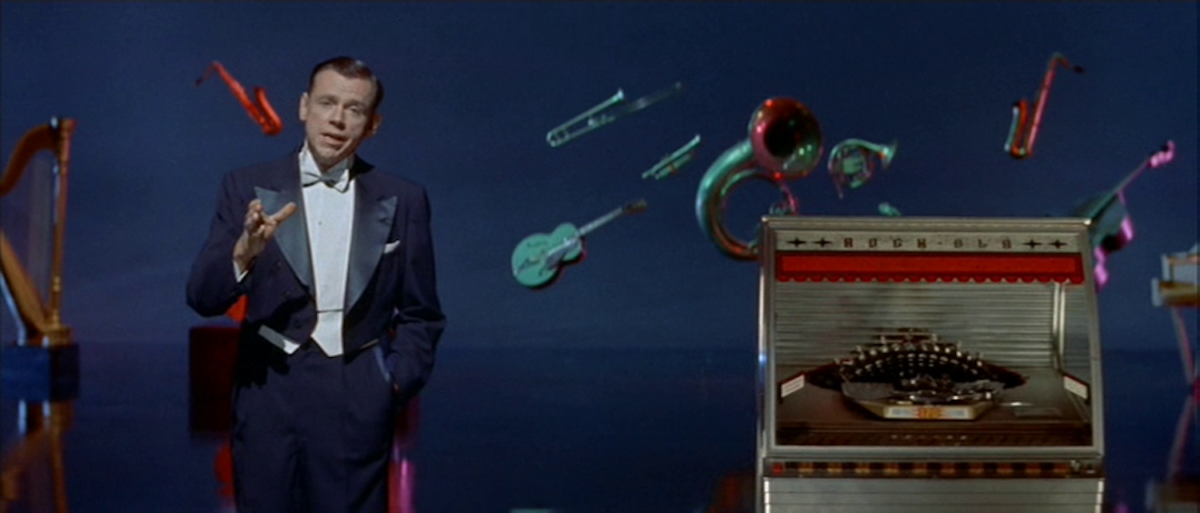

The movie opens with a direct address from Ewell. Rather than talk much about the forthcoming story, he talks about the image. It starts small, in Academy ratio, and in black-and-white, before Ewell snaps his fingers and flicks the edges; Deluxe color fades in and the image expands to fill the ultra-wide CinemaScope frame. Released after television’s first onslaught on cinema, the movie reflects how studios began to highlight the attractions that the “idiot box” at home could not provide. Ewell forgets to mention the most striking feature of the theater, perhaps because it was not in Twentieth Century Fox’s press kit of big-money innovations: the company of strangers, evidence of a real world beyond the viewer’s living room. As Ewell continues talking, a jukebox starts blasting Little Richard singing the titular tune. The music gradually drowns out Ewell’s voice, and the camera dollies towards the jukebox, like a teenager drawn to a party happening outside their window. Cut to the opening credits, adorned by dancers rocking out to Little Richard’s howl. Through this gesture, the cinema is no longer the place of aspect ratios and frame rates, but a nightclub where strangers grab onto each other and dance their hearts out. This is the first of many musical gestures which bring out The Girl Can’t Help It’s tactile world.

The Girl Can’t Help It doesn’t feel like many other musicals. All but one of its numbers were written prior to the movie’s production, and the plot chooses to avoid the jukebox musical trope of finding threads between its songs’ themes. The music, then, lacks the self-reflexivity of classical musicals like The Band Wagon (Vincente Minelli, 1953) or newer spins like The Hole (Tsai Ming-liang, 1998), with its winking incongruity between situation and song. Writing on the classical Hollywood musical, Rick Altman frames the use of a song as “the timeless interlude, the brake, indeed the break that sets up a signifying relationship between narrative flow and musical stasis.”Altman, Rick. The American Film Musical (1987), p. 102. Songs in The Girl Can’t Help It arrive at the head of a scene, prefiguring the narrative rather than interrupting it. The music is diegetic but mostly unrelated to the plot, which gives the two elements space to coexist. Lower-budget rock and roll movies from the same era, with titles like Rock Rock Rock or Don’t Knock the Rock (both 1956), would often cast musicians in the lead roles, constructing plots around a school dance or other climactic performance in order to showcase their singing.

There’s a shockingly tender moment towards the middle of the movie, during a performance by rock-and-rollers Gene Vincent and His Blue Caps. The camera cuts behind Vincent to one of the Blue Caps’ guitarists, Paul Peek, lost in violent strumming. After the cut, he composes himself and lifts his head to face Vincent and follow his downbeat. It’s tender in the masculine love reflected off the gleam in his eyes, a small moment of order amid so much noise; it’s shocking in the way it clashes with the band’s bad boy image, and for the microscopic attention paid by Tashlin, whose comedy can appear so broad. There is a comedic aspect to Peek’s monomaniacal pursuit of the beat, his hair spilling over his eyes and an unintentional smile stretching from ear to ear. But that cynical laughter is countered by the joy he expresses, of participating so fully in a moment as to lose himself. Performers in musicals often share a look in the moment before a song bursts out, both to communicate the timing and to prepare for the formal breach. Peek betrays no knowing glance; he is entirely engaged in playing music with the band. Even in its funny aspects, Tashlin’s world is actively lived in, rather than crafted specifically to land a certain joke.

Early Tashlin evangelist Ian Cameron notes this realistic impulse, contrasting the director’s movies with the more manufactured Modern Times (Charles Chaplin, 1936) and Mon Oncle (Jacques Tati, 1958). A distrust of modern technology pervades all these works, but where Chaplin and Tati focus on gadgets that have been “invented to be funny”, Tashlin sources his objects from the actual world: Cameron cites the washing machine in The First Time (1952), power-operated car windows in Marry Me Again (1953), and the punch card computer in The Man From the Diner’s Club (1963)—all new inventions at the time. Tashlin participates in the modern world, giving his critiques an ambivalence that reflects a more widespread perspective on our techno-society than that of a total ascetic. “Tashlin is not aiming to work on the unacceptably rudimentary level of rejecting society as a whole”, writes Cameron. “How can he detest automation when each new piece of apparatus opens a new range of comic possibilities?”Cameron, Ian. ‘Frank Tashlin & The New World’, in Movie, no. 7 (1963), p. 16.

Rock and roll is Tashlin’s apparatus du jour for The Girl Can’t Help It. Before its many decades spent slipping in and out of the mainstream, rock music in the 1950s was considered a passing fad, unappealing to anyone aged past its adolescent scowl. Tashlin could have commissioned a slate of tunes custom-made to highlight the laughable elements of rock and roll—untrained voices, inane rhymes—in the vein of the fictional gadgets in Modern Times and Mon Oncle. Instead, original acts perform their own material, often the Black artists whose work had been repackaged by white ones. Almost all the shots of the musicians are framed to exclude any audience members, until their final applause, so as to give them their own space as the creators of music rather than as just the object of listening. The film cuts between a few fixed points in front of the performers, resulting in striking CinemaScope compositions, but also reflecting how they would appear on television—live, capturing an electric moment. In classic Tashlin style, this parody is also a recognition of the device’s virtues, even of the device that the movie is, from its first moments, set against.

The one scene that centers around a television continues the ambivalent celebration. Murdock, in his attempt to make Jerri a star, instructs Tom to watch the television, where Eddie Cochran gives a performance of ‘Twenty Flight Rock’ on a variety show. The shots of the screen call back to the opening: the camera pointed at it is zoomed in so far that the wings of the cabinet take up the extra space that CinemaScope provides, leaving an Academy-sized square in the center for Cochran to perform in. Cochran’s is the most conspicuously sexualized performance; the song describes the disastrous effects of climbing the twenty flights to his girlfriend’s room on his ability to “rock”. The eighteen-year-old’s hips move faster than Elvis’s, jittering across the stage floor. The scene progresses through gradually more zoomed-in shots of the television set, which are matched by closer shots of Cochran himself. The closer we look at the screen, the closer Cochran looks at us, as if he and his ravenous gaze are reaching out of the television. Televisions are often used for humor throughout Tashlin’s movies, such as the goofiness of their antennae in Rock-a-Bye Baby or their ear-splitting advertising jingles in Will Success Spoil Rock Hunter?, but the joke here highlights their function as a site of community. Murdock, Tom, Jerri, and Tom’s maid all watch simultaneously from separate living rooms, and Cochran seems present in his own way. Just as he sings about scaling twenty flights of stairs, the television signal carrying his image does its own traveling through the airwaves—placing Eddie Cochran into the same physical world as the living room, rather than staying cloistered in the small screen.

A similar investigation into television cropped up in the previous year’s It’s Always Fair Weather (1955). The Stanley Donen musical climaxes in a television studio—itself shooting a musical revue—featuring many parallel CinemaScope framings of small screens to The Girl Can’t Help It. However, Fair Weather’s screens are designed to look one-dimensionally shabby: they are in black-and-white, and by situating the action in the studio, many of the cuts serve to contrast the rich film image with the limited television one. Characters smile and gesture for the cameras, a distinct performance for the viewer, as opposed to the sexual urges of Cochran that commune with the viewer. Gene Kelly coaxes an on-camera confession from his antagonist, after which the cops burst in to make a swift arrest. The one virtue of this new technology is shown to be its propensity for surveillance and policing. There is a harsh realism to this scene in Fair Weather, presaging CCTV and facial recognition, but it is born out of a description of the world within a small arena—the television studio or its other self-contained sets. The film invites us to watch its characters being watched, paralleling the self-conscious musical numbers that Kelly and company break into and establishing a level of distance entirely foreign to the music in The Girl Can’t Help It. Eddie Cochran’s performance is real not because an all-seeing eye is trained on it, but because he is considered as participant rather than spectacle. His music-making is not separate from life, but an activity that he does, as real as walking up the stairs to his girlfriend’s place.

This interplay between the fiction of the plot and the physicality of the performances recurs constantly throughout the movie, including Gene Vincent’s number. Until that point, the performances have run on a parallel track to the plot, mainly serving as background noise to Mansfield’s sashays through the nightclubs. Following this scene, however, the cast begins singing themselves, sharing the screen with real-world acts. Tashlin marks this transition through a series of rhymes. The camera starts on the exterior of the Beaux Arts Rehearsal Hall, then pans upstairs to reveal three open windows, one of which contains Vincent channeling his sexual frustration with ‘Be-Bop-A-Lula’. The film cuts back to the entrance, this time to watch the characters move upstairs. Ewell demonstrates a similar sexual undertone through his dialogue: “We need a room—to rehearse in.” When they get upstairs, Mansfield returns the innuendo with, “I’m ready”—which is also a reply to the guitarist eyeing Vincent’s downbeat. As the scene cuts between Vincent’s band and Mansfield’s rehearsal, the volume shifts up and down, emulating the experience of walking through a loud concert venue, or even a bustling city street while someone plays music on the sidewalk. There is a realism here, not necessarily of a realistic situation, but in the way that the performers inhabit this physical space. Mansfield and Ewell’s characters exist as ghosts, moving into the space of the rehearsal hall. Vincent’s singing scores the movement from fiction into reality.

Mansfield does, in fact, appear as a ghost in the scene immediately prior. Ewell’s character is an alcoholic because his wife, real-life singer Julie London, left him. Every time he hears her song emanate from a distant jukebox or, by a masochistic act, from his own record player, he sees an apparition of her. We watch her haunt his house, the two of them flanked by post-war signifiers of domesticity—stand mixer, refrigerator, ostentatious stone hearth—until she and her harsh shadow walk down the foyer stairs, a common site of sexual frustration for Tashlin. A few scenes later, we hear London’s song in a nondescript bar, though now Mansfield takes her place, appearing static and with no shadow—even less corporeal than London. From the start, Mansfield’s character appears to Ewell’s as unreal, a gift from on high designed to fill his lack. She first appears noiselessly, from behind his back, and later comes to him with a bottle of milk over each breast, showing him her promise as a housewife without speaking a word. She cooks, cleans, does anything that will stress her domestic qualities. She doesn’t walk; she glides.

Movies are no stranger to this flavor of wish fulfillment, especially not in a genre so predicated on it as the musical. The twist that Mansfield provides, however, is separating that out-of-world force from the musical interludes. Her character has no interest in singing: until the final scene, the closest she gets is imitating a police siren. Where many musicals may use song as a way to step out of the story’s surface—either into a character’s head or into utopian imagining—The Girl Can’t Help It locates that mechanism within Mansfield, freeing the songs to allow further engagement with the material world. Mansfield and the musicians are brought into close contact throughout the early scenes in nightclubs, where her ghostly strolls grant the songs their earthly power.

The first look we get of Little Richard in the nightclub is of his feet. From that grounded angle, the camera pans up and dollies back to show him singing from the center of the club, on the same level as the patrons watching. Though Little Richard was known for his eccentric performances, he barely sways from side to side here, and the camera stays close on him whenever he does move. The effect may be isolation, but the aim aligns with Tashlin’s goal of realism in his musical acts. In his live shows, Little Richard’s dancing needs no assurance of reality. It has a “He’s really doing that!” energy that the repeated takes and careful editing of a film strips away; viewers knew that he will not break a bone on camera, or they would have read about it in the papers weeks ago. The same year’s Don’t Knock the Rock, a significantly cheaper rock and roll vehicle, takes a more straightforward approach of capturing his usual live antics: a leg on the piano, his saxophone player dancing on its lid. The shots are framed to include the audience members looking on. They observe Little Richard like he is a man from outer space, and, for the purposes of a movie meant to highlight the wildness of this young music, he is. In The Girl Can’t Help It, Jayne Mansfield is the one from outer space: her form-fitting dress makes her look like a cartoon character, as does her mechanical gait, and she follows Ewell’s script of responding to any question with “Ask my agent.” Compared to the imposition of Mansfield, Little Richard is naturalistic—a living person rather than a spectacle.

Is Mansfield sacrificed, then, to humanize the men in the movie? Mansfield’s character—and Mansfield herself—is being forced into selling her body as a celebrity, and her only path out is to become the perfect domestic wife for Ewell. She is nothing short of a Mizoguchi protagonist, hemmed in by her body and aware of its most minute twirls. Removing her fur stole to walk the club floors, she echoes the line of women stripping to entice the painter in Utamaro and His Five Women (1946). Who knows if, prior to the events of The Girl Can’t Help It, she was passed between abuses as in The Life of Oharu (1952), picking up survival skills along the way?

Unlike Mizoguchi’s heroines, though, Mansfield refuses pity. A moment like the aforementioned breastmilk innuendo—symbolic, laughable, over-the-top—demonstrates the extent to which she was in on the joke, playing the part of the “ideal woman” to an all-knowing tee. That self-knowledge manifests in her flawlessly bleached hair, robotic incantations, and most of all her blank stare, which betrays not a blank mind but rather a mind beyond the film’s story. Like the traveling musician Serafin in The Pirate (Minelli, 1948), she plays the role of the outsider, only she never breaks the movie’s form to assert herself, as Serafin does through song. Instead, she does it on the fringes, with her ineffable glances to Ewell, or her varied intonations of “Ask my agent.” Tashlin would go on to direct her again in Will Success Spoil Rock Hunter?, where she plays Rita Marlowe, a character who looks like Mansfield, has acted in the same movies as Mansfield, and even has Mansfield’s real-life husband.

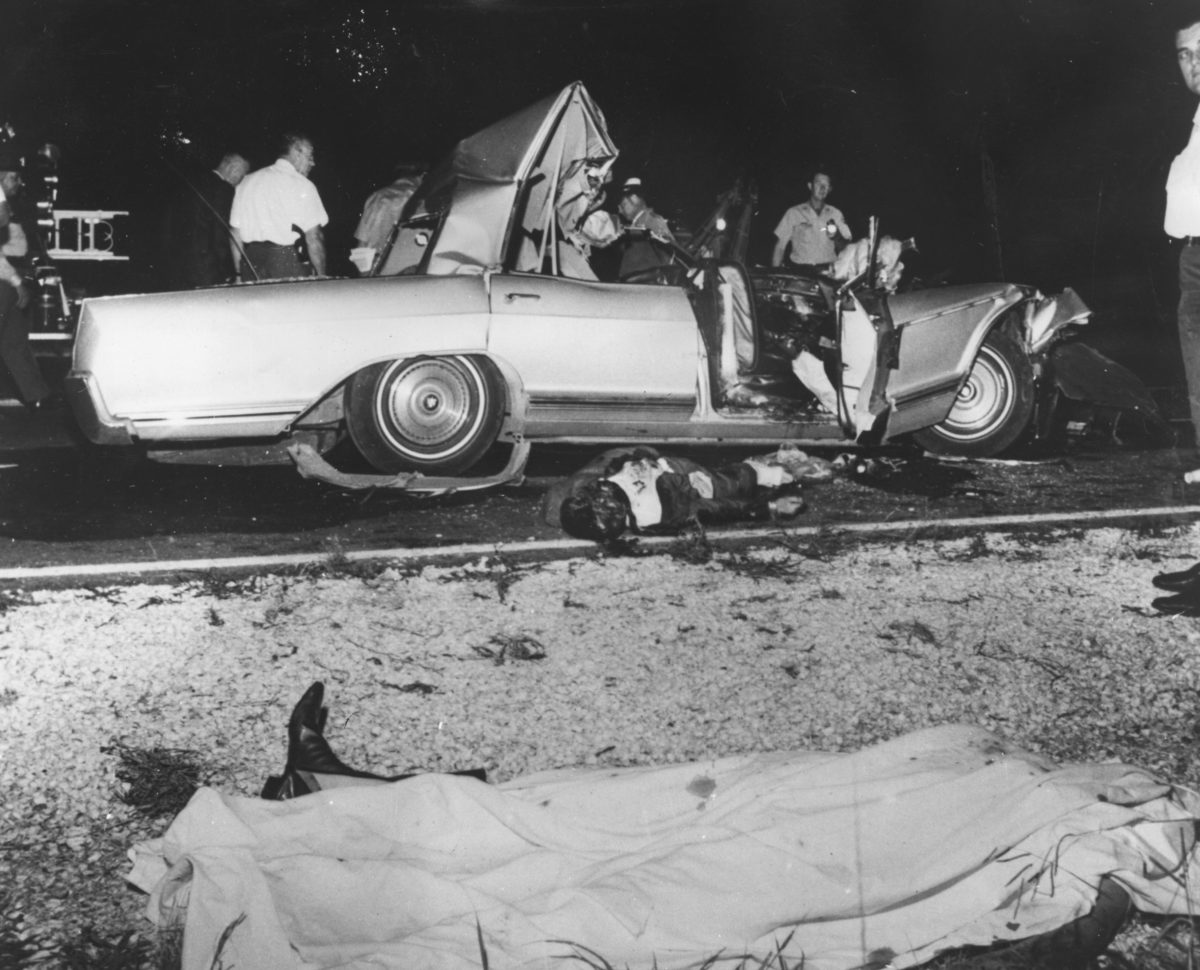

While explicit in Rock Hunter?, there is the same continuity between character and actor in The Girl Can’t Help It. At press conferences and photoshoots, Mansfield was constantly aware of her image, oscillating between performing the knockoff-Marilyn archetype and bragging about her high IQ. In one photoshoot for LIFE magazine, she poses with dozens of inflatable facsimiles of herself, the real-life one smiling amid the sea of her reproductions. Even the image of her gruesome death, immortalized in Kenneth Anger’s Hollywood Babylon, looks curated: body covered by cloth in the foreground, blonde wig caught by the windshield in the background. Though her character in the movie exists as the projection of the men’s desires, she is the force that frames the action: take, for example, the sequence in Ewell’s kitchen, where each reverse shot includes her cleavage, even when it necessitates a jump cut. Gene Kelly was often credited as director next to Stanley Donen for his ability to control the film from in front of the camera, to be both within it and without it; Mansfield should be considered the same next to Tashlin.

Mansfield’s highest moment of surreptitious acting corresponds with the movie’s most striking performance, ‘Spread the Word’ by Abbey Lincoln. This final nightclub song sounds more gospel than rock and roll—there were more porous boundaries—but Lincoln’s voice contains all the same immediacy as Gene Vincent’s or Little Richard’s. She commands the entire frame, sharing it with neither the crowd nor any bandmates, just the glittery blue curtain behind her. Despite the similar composition to the movie’s fourth-wall-breaking opening, Tashlin carefully records her so as to make her real without turning her into a stage-bound spectacle. Her dress reflects on the stage below; the camera dollies in and out and changes the lighting partway through, all to show her as a physical entity sharing the same space with the rest of the movie. When the film cuts to Mansfield in the audience, she taps in exact time with Lincoln, then gets up to do her strut. The owner approaches her and she blurts out an accidental complete sentence, “Please, I’m going to the powder room!” instead of her prescribed “Ask my agent.” She breaks her usual timing as well, talking over the man instead of taking the long pauses she had previously. “Oh, that was an ad-lib”, she whispers to the side, before giving a curt “Sorry, ask my agent.” Mansfield the actor and Mansfield’s character both say the aside, the latter bucking Ewell’s script and the former bucking the movie’s. Her delivery defies discussions of irony; she moves too fast, ending with a quick salute and a twirl into the powder room. She soars above the screen, even above the audience who is aware of her games. It’s only fitting that the film cuts back to Lincoln, who raises her arms and sings, “Speak the truth, it will be heard / Glory be, and hallelujah! / Spread the gospel, spread the word.”

The truth, if it were Tashlin speaking it, is to dance, participate—to constantly do. His movies betray a certain naivete, even traditionalism: his fascination with modern gadgets is matched only by his love for the happy family. Nearly all of his movies end with an image of a couple in love, often with children in tow. He is far from the only director to end with marriage—the Hays Code nearly mandated it—but his endings seek more to revel in the Tashlin philosophy of physical participation rather than to reify the myth of the suburban family. A case in point is Tashlin’s Hollywood or Bust (1956), which dramatizes a Jerry Lewis character’s cross-country quest to realize his love of Anita Ekberg, whom he only knows from her movies. Rather than entering his silver screen dream, however, he meets her in the flesh, even crashing violently into multiple studio shoots. Their love and joy is in the moment, the interaction of their bodies made physical and real, though it started from a filmic fantasy. The film ends with an image that could sum up Tashlin’s entire career. Lewis and Ekberg, paired with co-stars and makeshift family Dean Martin and Pat Crowley, sing the title song arm-in-arm. They walk with the audience, out of the theater and out into their lives.