Nha Fala (My Voice, 2002) was Flora Gomes’s fourth film, after a trio of films set in his native Guinea-Bissau. It is dedicated to the capital city of Bissau but in fact was filmed in Paris and Cabo Verde, the nearby island nation that was also colonized by the Portuguese. It’s arguably Gomes’s least African film to date, a Portuguese-French-Luxemburgish coproduction with no shortage of European actors. On the other hand, a case could be made for it as Gomes’s most pan-African film. Made in memory of Amílcar Cabral, the revolutionary orator who led both Guinea-Bissau and Cabo Verde’s struggles for independence from Portugal and whose bust becomes the film’s defining comic motif, it exudes a Lusophone creole identity the likes of which have rarely been seen on the big screen (though Cabo Verde’s hilly seascapes themselves were on ample display in Pedro Costa’s Casa de lava). It is also as much Gomes’s film as the Cameroonian master Manu Dibango’s. Dibango, whose epochal contributions to the nebulous category of “world music” have been sampled by the likes of Michael Jackson and Rihanna, didn’t only wrote and composed the songs that serve as Nha Fala’s spine but even played sax throughout.

The majestic opening scene, following a quintet of children carrying a dead bird on a gurney along the shore at sunrise, already establishes the film as a sensuous sonic experience. The quiet humming of a girl’s voice is mixed perfectly with the sounds of the children’s footsteps. It also sets the tone that will run the film’s course: grief sitting always at the edge of exuberance. Death is treated with levity, as something to have fun with, throughout. In this case, the kids want everyone in town who has ever been a friend to their classroom parrot to be able to say goodbye.

Though, like Gomes’s previous films Mortu nega (Death Denied, 1988) and Po di Sangui (Tree of Blood, 1996)—to this viewer’s mind, among the very best of sub-Saharan African cinema—Nha Fala meditates on pain, loss, and the traumas of colonialism, it is staunchly a musical comedy, fully embracing its tropes whereas his one other earlier feature, Udji Azul di Yonta (The Blue Eyes of Yonta, 1992), merely flirted with them. It announces its comfort with frivolity during the opening musical number that engulfs our protagonist, Vita (Fatou N’Diaye, whom Belgian cinephiles will recognize from her starring role in Koen Mortier’s recent Un ange), when she sidesteps her relentless suitor Yano on her way to church. Her fellow congregants announce they need to vote for a new choir director and launch into a series of campaign speeches by song. The lyrics, in which each member lays a different claim to leadership potential (“I’m the smartest”, “I’m the richest”, “I’m the poorest”, and so on) belie a sardonic view of all political discourse.

The second musical number, ‘Os Bons Conselhos’ (‘Good Advice’), trades in the first’s melodic jazz fusion for a more propulsive calypso beat, but it serves a similar function of poking fun at social issues and concluding with a cynical outlook. Various people regale Vita with words of wisdom for her to take with her to Paris, where she has won a full-ride to university. The men in the throng lament that their degrees are useless after the postcolonial economic miracle has run its course. The children who tell her more simply to be careful. She responds with acerbic advice of her own: “Build coffins—the only sure thing in this life is death.”

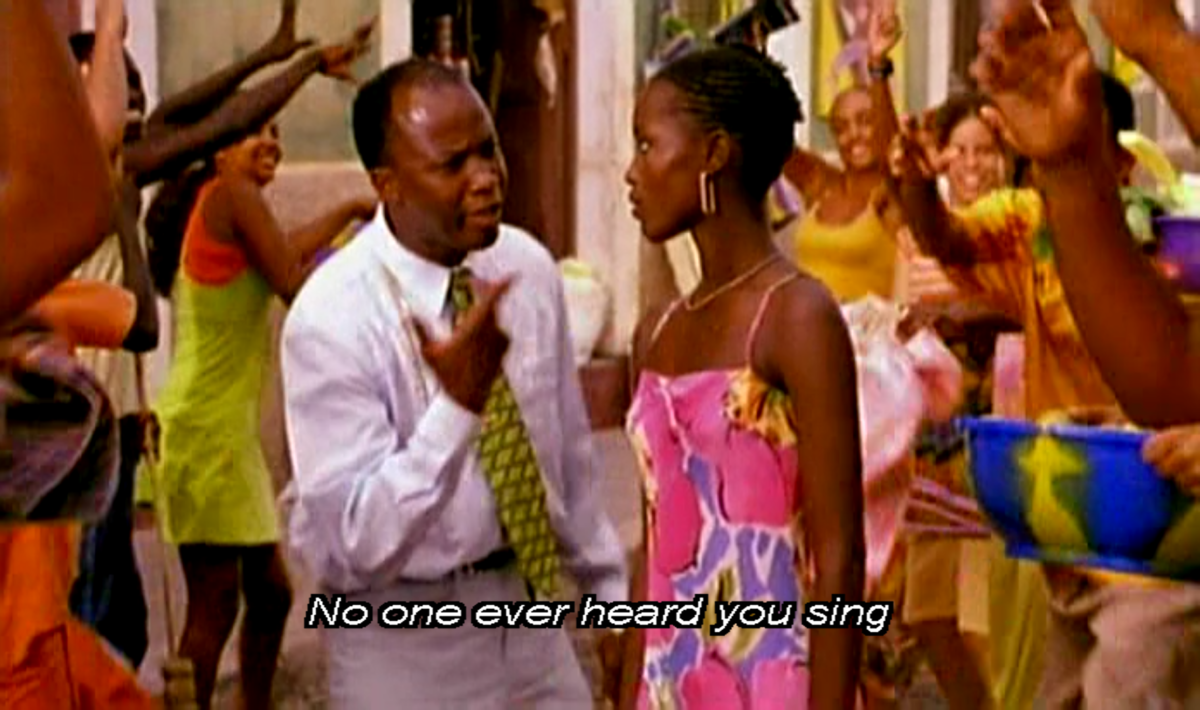

Death, we soon learn, is intimately bound up with music itself for Vita. The irony is that she only really comes to life, so to speak, in the film’s musical passages once she has acknowledged her family’s perceived curse: that, like swans, singing will kill them. In the songs that precede this admission, her pessimism about life stands in stark contrast to the vivacity of her community perpetually erupting in song around her; this is most clearly on display in a dazzlingly well-integrated third song, in which Yano tries to convince Vita not to go to Paris and to marry him. Perhaps the most musically stirring of the songs, employing counterpoint between sugary pop choruses and percussive hip-hop verses, it is also the dance centerpiece of the film, with bystanders in the street seamlessly transforming into background dancers with a whole lexicon of moves.

The gyrations of the crowd are also used to great effect in the fourth musical number, that serves as Vita’s send-off to Paris and also closes one of the film’s life-cycle loops since it ostensibly serves to praise the birth of a newborn boy. (Amongst several plot lacunae is the fact that we never really get a glimpse of this baby or his parents.) It toggles between medium shots that immerse us in the crowd that’s shown up to partake in the celebratory feast and long shots that take in the whole spectacle.

An abrupt cut to an aerial pan to the left, scanning the Eiffel Tower at a canted angle, literally flings us with Vita to Paris, though the song that begins concomitantly reveals to us that she has outpaced us to the City of Light. From the sky, we land on the rue du Faubourg du Temple, where her neighbors bop around in their shared courtyard to recount all of the wonderful things she has done and brought to their lives. If it is amusingly jarring to see these Parisians grooving to the Afrofunk beat in celebration of interracial romance (Vita has fallen in love with a nice French boy, Pierre), then the subsequent number is downright stupefying. Vita goes to meet Pierre’s parents at the brasserie they own, and the hustle-bustle as the staff gets ready for lunch service gives way to ‘Adieu XXe siècle’ (‘Goodbye 20th Century’), a boisterous lament of Europe’s colonial past. The lyrics themselves are clumsy in an In the Heights way, but the mere spectacle of seeing a group of white Europeans performing the number for their new West African friend deserves praise.

Their gift is returned to Pierre in spades, though, by Vita, who agrees to conquer her inherited fear of singing and record a song in his studio (fittingly titled ‘La Peur’) on the condition that he will then come live with her back home. (Let’s not forget that the transnational is always a step away from the transactional.) The only catch is she is convinced she will need to stage her own death in order to fulfill the prophecy with which her mother raised her, that if either of them is ever to sing, they will die, though perhaps to be reborn. This plot point made more sense to me on second viewing when I noticed several signs noting businesses were closed for “falecimento” – Portuguese for death. “Fale” is one letter away from the most important thing to Vita’s story, “fala” (“voice” in Kriolu, “speech” in Portuguese), so her passing away is already inherently linked to her concretizing her own voice (“cimento”, it turns out, is the word for cement). Indeed, as one of the two men who finally decide where to mount the bust of Amílcar Cabral that was being tossed around in the first act declares in the film’s closing moment, “He says that the end is the beginning.”

While Nha Fala is most directly about a mother and daughter conquering fears or superstitions, it also relatedly seeks to envision historical closures as in fact openings to the future. The countries that Cabral led to independence have their entire lives ahead of them. The musical may seem an odd vehicle for this type of historiographical reflection, which is a unifying thread of Gomes’s filmography. Yet, from Brazil to India to even North Korea and the People’s Republic of China, it has long been a hormone for imagining national identity. A folk art through and through, the musical addresses a people. In this case, it would seem to be necessarily the “Afropean” community. Examining the politics of immigrant life in and out of France, Nha Fala bears comparison to the late great Burkinabé filmmaker Idrissa Ouedraogo’s Le Cri du cœur (1994) and—particularly in its youthful exuberance—to Salut cousin ! (1996) by the Algerian-born Merzak Allouache. But there are at least two other audiences whose curiosities and modes of reception would be fascinating to consider: the people of Cabo Verde and Guinea-Bissau, of course, as well as dispersed fans of “world music” (unfortunate though the term may be), a market and community largely untapped by the film musical, whose relationships with record labels and studio musicians have never been easy, nor consummated as could be.