Movie theaters started to reopen this summer, and with them came not a rebirth of cinephilic delight (for that, we’ll perhaps have to wait for studios to demolish theatrical windows entirely, clearing the space for an indie renaissance, or—more likely, though no less farfetched—for 35mm repertory screenings to become the new vinyl) but at least two specimens of a once prized object of movie desire: the musical.

The chatter around these films, In the Heights (Jon M. Chu) and Annette (Leos Carax), has largely anchored itself (but what doesn’t these days?) to the politics of representation. Where are all the Black people in Hollywood’s vision of Washington Heights? And who is this saccharine, lustrous fresco of working-class urban life really for? Meanwhile, why does Henry McHenry get to live in such a nice house if he’s such an eccentric, alienating performance artist? Does Leos Carax give a rat’s ass about anyone but himself? [Leave it to the guy whose pseudonym roughly translates to “The Oscar goes to…” to make a cockamamie English-language debut that ends in “movie jail” with its protagonist turning his back to the camera, revealing a verbal link to his maker (“LLXXX” adorns his jumpsuit), and declaring, “Stop watching me.”] Where, to put it bluntly, do we the beleaguered, TV-weary masses yearning to break free from COVID-19 fit into all of this?

Both movies left me void as I stumbled out of the multiplex into the summer sun—no mean feat, as the hunger for big-screen experiences had earlier in the season nullified my critical capacities and turned even Oscar bait into holy water. Part of the problem with both was undoubtedly the music itself. If the hip-hop fusion of Lin-Manuel Miranda’s showtunes felt like an awkward relic of the ‘90s (when he originally wrote the musical), then Carax’s alt-rock opera recalled an era no one is particularly nostalgic for—the early ‘00s, when Sparks’ Lil’ Beethoven was released, Baz Luhrmann’s Moulin Rouge! inaugurated a Hollywood musical renaissance, and jukebox musicals were all the rage on Broadway.See the Wikipedia article on the jukebox musical.

It is important to remember that the history of self-reflective film musicals is contiguous with the history of film musicals, period. When The Jazz Singer (Alan Crosland, 1927) introduced synchronized song to the medium’s repertoire of magic tricks, it created a tradition of making the very miracle of sound technology the musical’s implicit subject. Rare are the musicals that do not figure musical performance or production at all into their diegetic narratives. Basically, most filmmakers want to at least partially rationalize why characters are breaking out into song.

Jane Feuer writes in a classic essay on the genre, “The heavily value-laden oppositions [ed. note—for example, between high and low art] set up in the self-reflective films promote the mode of expression of the film musical itself as spontaneous and natural rather than calculated and technological… The myth of spontaneity operates […] to make musical performance, which is actually part of culture, appear to be part of nature.”‘The Self-Reflexive Musical and the Myth of Entertainment’, in Barry Keith Grant, ed. Film Genre Reader III, 3rd. edition (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2003) 463. Originally published in Quarterly Review of Film Studies 2, no. 3 (August 1977).

A common theme in this issue is how the musical, with its wide-eyed fixation on the corporeality of performers, inherently dissolves the line between actors and characters. This captures, in miniature, the genre’s almost unwieldy power of toppling over any steady boundaries between reality and fiction. (Further reflection on these categories might lead us to contemplate the very concept of music, which is naturally occurring and yet in many ways the most nonsensical of all arts.)

Jack Seibert considers the tension between documentation and mythology in an auteurist reading of early rock n’ roll musical The Girl Can’t Help It (Frank Tashlin, 1956), examining not only Tashlin’s complicated relationship to new technologies but also to new icons of it, including Jayne Mansfield and Little Richard.

Patrick Preziosi makes an unlikely pairing of contemporary filmmakers, Tsai Ming-liang and Terence Davies, to show the complementary ways they use musical numbers in confronting the inexorable burden of history.

My own essay, on Flora Gomes’s Nha Fala (My Voice, 2002), looks at the musical as a “glocal” shamanic practice, with its healing powers and propensity for moving across cultures.

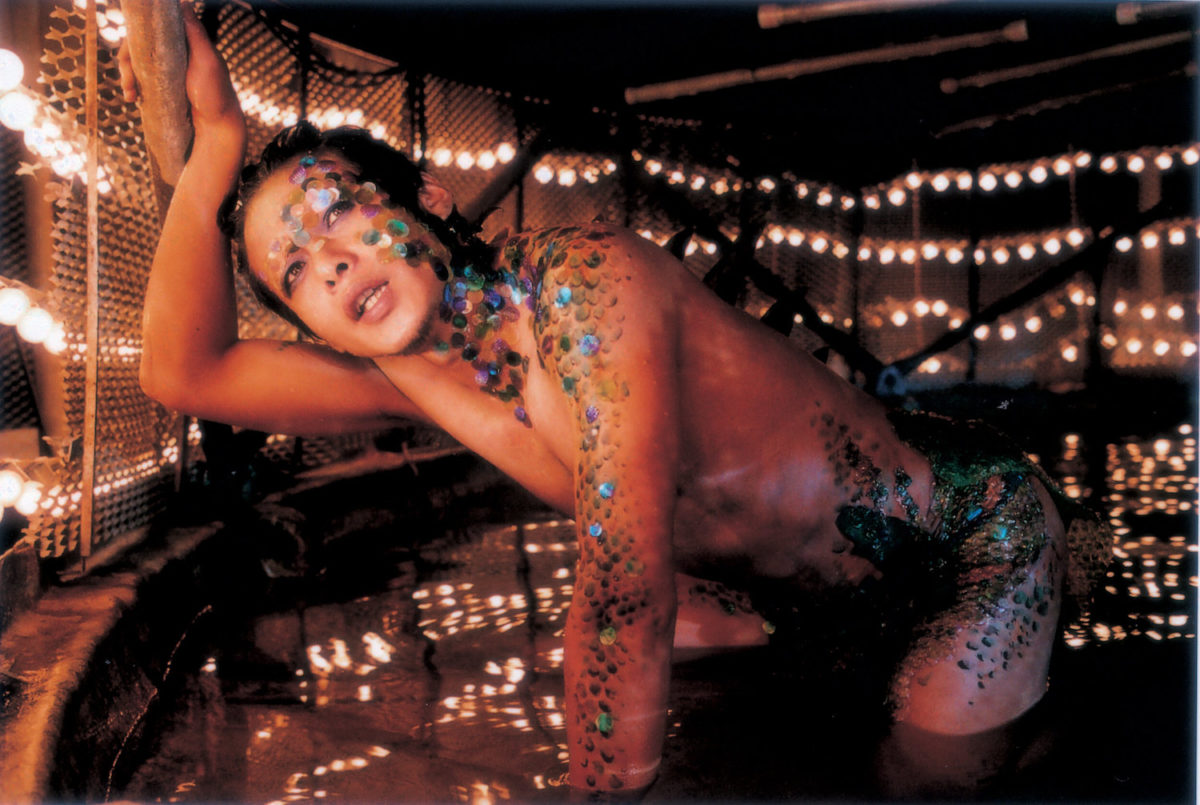

Savina Petkova’s deep-dive essay into The Lure (Agnieszka Smoczyńska, 2015) illuminates the genre’s porosity, enabling it to think through the body (in a way one would typically associate with horror), reimagine a canonical fairy tale, and engage with questions of national memory.

Cláudio Alves doubles down on the musical’s fraught relationship with realism through an analysis of Technoboss (João Nicolau, 2019) that also gives us a crash course in the history of Portuguese cinema with field trips to postwar Cinecittà and Paris in the ‘60s.

Perhaps reading through this issue will serve as a balm to those who, like me, wondered how the musical found itself in such a dire place in 2021, how the genre that took hold of the American imagination during the dark days of the Great Depression could now deliver us so little force. I would love to know what was in Spike Lee’s and his jurors’ hearts at Cannes when Annette graced the Palais. All I do know is that the final revelation of the film was a hostile antithesis to the carefree escapism that the genre was made to deliver. The only shred of hope this movie gives us is that Jeff Bezos’s evil empire could get behind such a withering assault on commodity fetishism.