Haruki Murakami has often been labelled a ‘cinematic’ writer. He observes, he lingers on images or motifs that obsess his characters, at times almost with the descriptive specificity of film scripts. There’s sometimes the casual reference to a character thinking that what they’re living through feels like the scene in a movie and from time to time we may get a name drop, like that of Jean-Luc Godard. Perhaps the trademark imagery he often employs also calls to mind a certain association with film: smoking, whiskey, sex, vinyls and jazz are all motifs that feel so intrinsically embedded into the visual language of cinema. After all, the noir and the French New Wave have done much to make the idea of a bohemian urban way of life of heavy smokers be inherently associated with cinema.

Yet, despite it all, the so-called perfect Haruki Murakami film adaptation may, in fact, never come to exist.

For one, Murakami himself may not even believe in adaptation to begin with; or at least not in the traditional sense. For a good while he has been sceptical of the idea of adaptation altogether, even if, lately, he seems to have become a bit more keen on giving away the rights for his shorter pieces, at least. Asked his opinion on Ryûsuke Hamaguchi’s Drive My Car (2021) taking inspiration from his short story of the same name, the author was particularly happy with the fact that the film departed from the original text to the point that it didn’t feel like his work anymore.Haruki Murakami quoted in ‘Haruki Murakami and the Challenge of Adapting His Tales for Film’, Nicolas Rapold, The New York Times, November 2021 https://www.nytimes.com/2021/11/25/movies/haruki-murakami-drive-my-car-ryusuke-hamaguchi.html

The Farther Away the Fountain

As far as adaptation is concerned, Murakami does not care for fidelity or accuracy, but rather seems to encourage the act of interpretation. (Translations of his books also sometimes abide by this principle; for example, in some instances, his books were not translated from the Japanese original, but from their English translation, with Murakami gleefully endorsing the endeavour.) Recreating themes, atmospheres and feelings may matter more than exact words and situations. In fact, the farther away from the source the better, as he also remarks favourably about how Lee Chang-dong’s Burning (2018) reworks his short story ‘Barn Burning’: “By changing the setting from Japan to South Korea, it felt like a new mysterious reality was born. I want to highly commend these kinds of ‘gaps’ or differences.”Ibidem. A Murakami adaptation is thus free to depart from its source as much as it can.

But these ‘gaps’ can also be understood as a (self)awareness that the author’s particular style is hard to adapt cinematographically and that, inevitably, something will escape translation to the screen. As much as he may incite cinematic imagery, Murakami’s style of writing is very much grounded in text centred devices and techniques that have difficulty in lending themselves to the screen. There’s the characteristic use of first-person narration and retellings of events rather than action in real time, there’s letters or transcripts of cassettes—the beauty of which often relies on their textual qualities as reproduced in writing, and not on the image they may incite. With Murakami, much time is also spent inside the minds of the characters, and the idea of a heavy interior life is often not thought to be easy to translate to the screen.

That is not to say that the spirit of Murakami’s first-person narration is something that cannot be adapted to the screen at all. Chungking Express (Wong Kar-Wai, 1994), is perhaps more elusive and not often remembered as a Murakami adaptation per se, despite the fact that the story of the potential lovers missing each other by the millimetre is loosely based on the author’s (very, very) short ‘On Seeing the 100% Perfect Girl One Beautiful April Morning’. Wong is, in many ways, the ideal counterpart in cinema for what Murakami does in literature, with the director having at times cited the author as an influence or a reference, particularly for the monologues in Chungking Express.

Much like Murakami’s writing, most of Wong’s films are fragmented narratives governed by memory and a (generally male) inner voice engaged in a combination of fleeting, romantic thoughts, flashbacks, and witty, sometimes endearingly questionable considerations. Within Wong’s filmography, Chungking Express and Fallen Angels (1994) exhibit the most Murakami-esque tendencies, exploring the very particular mix of bemusement, ennui and disconnection of a modern urban life shaped by late capitalism and populated by escalators, supermarkets, and fast-food chains. Both films deal with the themes of accidentality, bizarre occurrences and mundane things elevated to heightened significance (as is the famous pineapple can), all concepts that guide life and, obviously, love in Murakami stories.

There’s also a perhaps accidental (sic) resemblance between Chungking Express and the first ever Murakami adaptation on film, Hear the Song of the Wind (Kazuki Ōmori, 1982), to the point that I wonder if Wong has ever seen the film and taken inspiration from it. The story of Hear the Song of the Wind is equally pushed forward by the monologue of its vaguely distracted protagonist, recounting past loves, women disappearing mysteriously and the idiosyncrasies of the people around him, notably his slightly dubious friend Rat (to note, Murakami characters often have unusual, quirky names). Dreams, evocative jazzy bars, recurring songs and disjunct to and fros between characters and memories feel analogous to the landscape of Chungking Express, but it is the features and the mannerisms of the main character (duly named “I”) that feel eerily reminiscent of Tony Leung’s Cop 663. It’s a certain restraint and detached serenity expressed through micro-gestures and looks that reminds of Leung, giving off the impression of someone assisting at life more than actually being involved in it. The Murakami protagonist by default is an insular, potentially heart-broken man with a very vivid internal life but of very few spoken words—a type that is also honourably embodied by Hidetoshi Nishijima in Drive My Car, with the same reserved, but meaningful passive coolness. What is further to note about the leads in Drive My Car and Hear the Song of the Wind is the touch of an intellectual higher ground that Murakami regularly resorts to in terms of his male characters, with Nishijima’s character being a famous theatre director (Kafuku) and “I” being a very knowledgeable jazz enthusiast. Tied in with the long-winded nature of their self-narrated thoughts, Murakami’s male characters can often appear as unlikeable and self-assured—something which Drive My Car manages to generally bypass by blocking access to Kafuku’s inner life and going for a more enigmatic and discreet figure.

Wong and Murakami are, of course, also bound together by Nat King Cole. Music is one essential and instrumental aspect of their artistic practices, ever so present in the worlds they create, be it as simple references, as ambiances that set the era and the tone or as recurring motifs that are of seminal importance to the story. But, most crucially, their approach to music is one that is nested in internationalism and multiculturalism. Except for perhaps the emblematic Faye Wong cover of ‘Dreams’ in Chungking Express, music in Cantonese or Mandarin is very rare to feature in a Wong film. Instead, what is preferred is either a nostalgic turn to ‘Quizás, quizás, quizás’-ian tunes of the 1960s or to pop culture classics like ‘California Dreamin’’ or ‘Happy Together’. Likewise, Murakami and his characters are obsessed with jazz and pianists belonging to an American cultural landscape, with references to Japanese culture being altogether minimal. In an interview with Tony Rayns‘Poet of time: Wong Kar-Wai on Chungking Express’, Tony Rayns, Sight and Sound, September 1995, https://www2.bfi.org.uk/news-opinion/sight-sound-magazine/archives/wong-kar-wai-chungking-express, being asked about the similarities between him and Murakami, Wong observes the following: “[H]e and I are about the same age, and we had very similar formative experiences: we were both marked by what I call ‘Seventh Fleet culture’ in those years between the Korean War and Vietnam. We both bought the music, the cigarettes, the lifestyle; seeing big foreigners on the streets made a strong impression on us.” Murakami’s frame of reference has thus always been one that extends way beyond Japan and towards the universal—if his stories do not actually operate within some sort of globalised multicultural utopia governed by popular culture.

“Her voice was like a line from an old black-and-white Jean-Luc Godard movie…”Haruki Murakami, Sputnik Sweetheart.

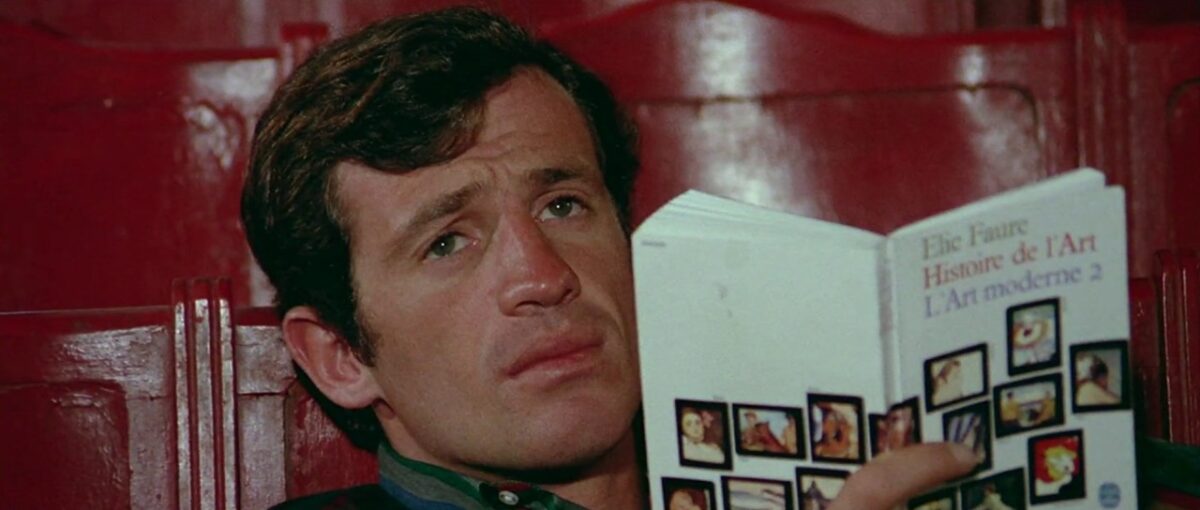

Murakami’s quirky cultured intellectuals will often make a reference to or quote from many things. Most of the time it’s world literature (Leo Tolstoy, William Faulkner, Ernest Hemingway, Thomas Mann, F. Scott Fitzgerald are some favourites), classical music and jazz. But there’s also the casual film reference, mostly to American cinema. The references to European cinema are certainly more limited, with Jean-Luc Godard and François Truffaut sneaking in only occasionally. In Kafka on the Shore, Truffaut’s The 400 Blows (1959) and Shoot the Piano Player (1960) are playing as a double feature, there’s a bit of paraphrase from Stolen Kisses (1968) in Murakami’s story ‘An Independent Organ’ and Godard gets referenced most notably in Sputnik Sweetheart and in After Dark, where one character names Alphaville as her favourite film—Alphaville also being the name of a recurring love-hotel in the story, that topically brings up ‘prohibited’ feelings of love. Also noteworthy here might be Norwegian Wood’s dig at university students who “get off listening to John Coltrane and seeing Pasolini movies”, further expanded into a commentary on young intellectuals who have become detached from the working class.

Godard and Murakami do have something in common, however. The playful techniques of pastiche and homage that Godard used in his earlier films (“the black-and-white ones”, to quote Murakami) are similar to how Murakami uses quotations himself. The Godard of the 1960s is laden with aphorisms and lines lifted from literature and spoken by cultured bohemians, never fully evident if in tribute or as parody. Breathless’s (1960) reverence toward American cinema, for example, is shared by Murakami via a constant adoration for Raymond Chandler and the occasional appreciation for Humphrey Bogart, as much as for Lauren Bacall (an extensive mention in Hard Boiled Wonderland and the End of the World). Despite being Japanese, Murakami’s characters live in an almost caricaturally American(ised) landscape—they go to Denny’s, listen to Miles Davis and debate whether to have Johnnie Walker or Chivas Regal—much like inside a less violent version of Made in U.S.A (1966).

Godard’s nexus of famous painters and classical pieces is also something that strongly resonates with Murakami. Both of them like to create compendiums of universal art, where references are mentioned only briefly, sometimes thrown in with no apparent relation to the story, left intentionally opaque or seemingly meaningless, but, eventually, adding up thematically and building a particular brand of syncretism and intertextuality. This is tied in with how both look at the 1960s as an essential moment in time that allowed cultural spaces to collide and merge together, and strongly influenced the way that the younger generation interacted with art, popular media and the world itself. To draw a final parallel between the two, it certainly helps that Godard’s pre-La Chinoise (1967) characters are often disengaged languid urban intellectuals, as is the case with Murakami’s most recurrent typologies. The greatest difference is, however, the source of this languidness, with Murakami’s early characters being the disillusioned, tired youth in the aftermath of Japan’s 1960s protests who have resigned themselves to late capitalism, while with Godard they are the internationally aware youth that will wake up to May ‘68 (and be disillusioned only later).

Aside from Truffaut and Godard, Murakami is not really concerned with any other French New Wave affinity. But, in terms of an unconscious cinematic kinship, a comparison to Jacques Rivette could provide an interesting point about how some of Murakami’s trademark practices are essentially not untranslatable to the screen and may actually benefit from much filmic potential. Hamaguchi’s Drive My Car already has a Rivettian feel to it in that it is centred on actors, theatre and performance, but what can be taken from Rivette and further applied to the idea of a Murakami adaptation are the ways in which the French director explores the tensions between various realities.

“…filtering in just beyond the frame of my consciousness.”

More than first person subjectivity, the other great challenge that Murakami poses to film adaptation are his constant shifts between parallel realities and touches of magical realism. The easy solution for it, one would think, would be to adapt through the medium of animation, as did Pierre Földes with his Blind Willow, Sleeping Woman (2022). However, in doing that, all tension with a palpable reality is lost. Animation may in this case offer slightly too much freedom, whereas the way in which Burning handles the idea of a cat that may or may not exist but is still being treated as part of reality seems like a more preferable approach, exactly because it maintains a collision between two planes of existence. There is a metaphysical sense contained within concrete reality that is put to question—as it most beautifully exemplified by Hae-mi’s pantomime routine about eating an imaginary tangerine in Burning. The key is not to imagine that there is a tangerine, but to forget that the tangerine doesn’t exist, says the character, creating a complex blur between imagination and reality, and making both exist at once. Hae-mi’s routine is a curious case where you can ‘see’ the invisible, making it a very clever moment that cements Burning’s approach to a reality that seems odd, uncanny, and, simultaneously, perfectly normal, but also incites wonder about what cinema as a medium can show and capture. Murakami’s odd realities and magical thinking may also resonate with Éric Rohmer, as they do with Wong Kar-Wai, subscribing to a heightened accidentality that results in situations (deaths, disappearances, accidental meetings of lovers) that are unlikely or unusual, but which do not essentially contradict the laws of reality.

A film like Rivette’s Celine and Julie Go Boating (1974) would perhaps resonate most with Murakamian dynamics in terms of navigating between realities, time periods and states of consciousness in which characters find themselves trapped. Rivette is evidently more concerned with a more playful, self-referential, meta-cinematic commentary on the medium, as show the repeated viewings and enterings of the pseudo-film/melodrama playing in loop at 7 bis, but the ‘down the rabbit-hole’ accumulation of magical elements that reorganise and reset reality feel congruous with the malleable matter of Murakami’s structures—as is perhaps best exemplified by Hard-Boiled Wonderland and the End of the World’s going chapter by chapter back and forth between ‘Wonderland’ and ‘the End of the World’ in two parallel stories. Julie and Celine meeting by chance and being bound together by an intuitive connection that is hard to understand rationally also feels similar to how Murakami’s characters decide to follow each other, although rarely in the same salutary and light-hearted sisterhood that the magician and librarian in Rivette’s film exemplify.

The Rivettian accumulation of unlikely conspiracies eventually turning likely that runs through Out 1 (1975) or Le Pont du Nord (1981) also bears some kinship to the odd occurrences of Murakami’s stories. Here can perhaps be named the investigative processes (or the curiously nonchalant lack of them) that happen when characters go missing or plots like the one in ‘Super-Frog Saves Tokyo’, where a frog shows up to warn a banker about an imminently disastrous earthquake in Tokyo. Rivette’s characters may bear a similarity to Murakami’s—or rather it is Murakami’s characters that bear the resemblance to Rivette’s—also in that they are often oblivious, not in a pejorative sense but in terms of their innocence, or in terms of their unawareness to realit(ies) shifting without their consent. Colin and Frédérique from Out 1 could fall under the same category as some mischievous and paranoid Murakami characters, but most particularly, it is Baptiste from Le Pont du Nord that elicits a strange, accidental akinness. There’s the detail of the unusual name—Baptiste is usually male-coded—and there’s an attitude of perpetual carefreeness guided by what she calls ‘fate’ or ‘hasard’. With Murakami, with Rivette, chance or fate governs reality, not in the sense of determinism, but rather in that of accidentality and chaos that could be as benevolent as malign. For Baptiste, another strata is her ambiguous nature—like with many other Rivettian characters, the border is a fine one between moral and immoral, or between psychotic and sympathetic, as also happens with a good part of Murakami’s characters, like the aforementioned Rat. No one is completely likeable in a Murakami novel or story, but there is still room for endearment.

Bingo

The cheeky observation made by fans and haters alike is that Murakami has a habit of rewriting the same story (see the “Murakami Bingo”), meaning that he repeats themes and situations often enough for his work to become one homogenous block of collected motifs of disappearing cats, mysterious women and insular intellectuals who have a thing for jazz. This allows for some leniency, in the sense that, ultimately, a Murakami adaptation may not even have to reference a story specifically—based on Murakami’s excitement at free adaptation, he might actually prefer this option more. However, the key to Murakami and his appeal, after all, might be the sense of familiarity that he brings. It’s a familiarity born out of his own repetitions, but also out of assimilating all the things he likes, as well as all the things ‘he’s like’. Murakami may share some accidental kinship to a lot of films that are not directly related to him in part because he’s built himself with the intent of responding to a cultural landscape where specificity (national or otherwise) is irrelevant and where culture itself has consistently become more and more mutable after the 1960s.