Emptiness, alienation, confusion, and apathy. These are not only the responses that Philippe Garrel elicits with his silent black-and-white film Le Révélateur (1968), but also the feelings the film’s three characters (mother, father, child) are immersed in. Rather than creating a world that is immediately recognizable, Garrel shows dreamed fears, more real than those that life brings with it. Watching Le Révélateur is like a prolonged waking up from a dream that leaves us with all kinds of feelings, without any memory of the dream itself.

What is essential about a dream is that it does not allow itself to be rationalized. In Le Révélateur, the narrative emerges from the gestures of the actors’ isolated bodies rather than from a predetermined plot structure expressed through gestures. No narrative, therefore, that could mediate the spectator’s reception of the images, instead forcing them to receive the film physically. Although what we see on screen creates a very physical viewing experience, the characters in the film have virtually no affective, physical connection with each other. This discrepancy between the corporeal distance between the characters, the near denial of the body, and the fact that the film imposes a sensory reception on the spectator constructs an alienation effect. Le Révélateur is a film that generates both a bodily and non-bodily experience, sensuous and nonsensuous at the same time.

With Le Révélateur, Garrel made a noncausal and nonlinear film. He harked back to the surrealist tradition of the Avant-Garde to create a film with the structure and form of a dream: fragmentation, contradiction, interruption and repetition. Garrel achieves this through long tracking shots, high black and white contrasts, overexposure, chiaroscuro (marvelously created with the minimal resources of a torch), dark Spilliaert-like landscapes of emptiness, and the surrealist staging for which the film is so well known. The social and political context of May ’68 weighs heavy in its absence. This film is not about the grand narrative of history, but about history on a micro level: how does a young family deal with it? Although in 1968 film in colour and with synchronous sound had of course long been possible, Garrel radically reverts to primitive cinema. In the late 1960s and the beginning of the 1970s many felt that cinema had exhausted itself, and so the New Wave was followed by a Neo-Primitivist turn. Filmmakers, among which Garrel, looked back to the early days of the medium, to the essence of it, to break cinema loose from how it grew up.

Not only in structure, but also in the positioning of the actors and representation of the cultural zeitgeist of the time, Garrel deviated from the social and cultural reality of May ’68. Although the sexual revolution took place in those years, which opened up space for a free experience of love, Le Révélateur is almost its antithesis. There is virtually no affective physical contact in the film. The only image of physical rapprochement between the parents comes at the very beginning of the film, in the pre-title sequence. The father puts a cigarette in the mother’s mouth, and tries to light it, but fails, the mother doesn’t cooperate. When he then tries to light her cigarette at the same time as his, it works. The converging cigarettes allude to a form of love and affection, perhaps a metaphor for making love, which is found almost nowhere else in the film. The child gazes at his parents’ gesture from the top of a wardrobe in the corner of the room, which hints at this scene being a metaphor for the boy’s birth.

Throughout the rest of the film, affection between the parents and the child is virtually non-existent. The characters/figures/bodies seem indoctrinated, at the mercy of the invisible phantoms of the self and the other. Their facial expressions remain in a constant state of emotionlessness and apathy. There is no scream for attention, no fight for affection, nothing but a deafening silence. The characters seem to have forgotten that their being has a bodily aspect to it and they have accepted that both for themselves and for the other. Their presence seems like a kind of triangle of bodies where the points (bodies) are connected—they are a family—but never coincide. If there is no sense of the exterior, there is no need for affection. Due to the lack of love and interaction, they seem to have become ghosts. What remains for the characters and the viewer is an emotionless delirium of unrequited desires, dissatisfaction, hopeless expectations, and unsaturated passions. While watching the film in the cinema, I became aware of my neighbor’s elbow that had been resting against my arm for a while. Out of politeness I didn’t dare pull my arm away—for the sake of not disrupting his experience—and this physical connection, minuscule as it may be, contrasted greatly to what I saw in the film.

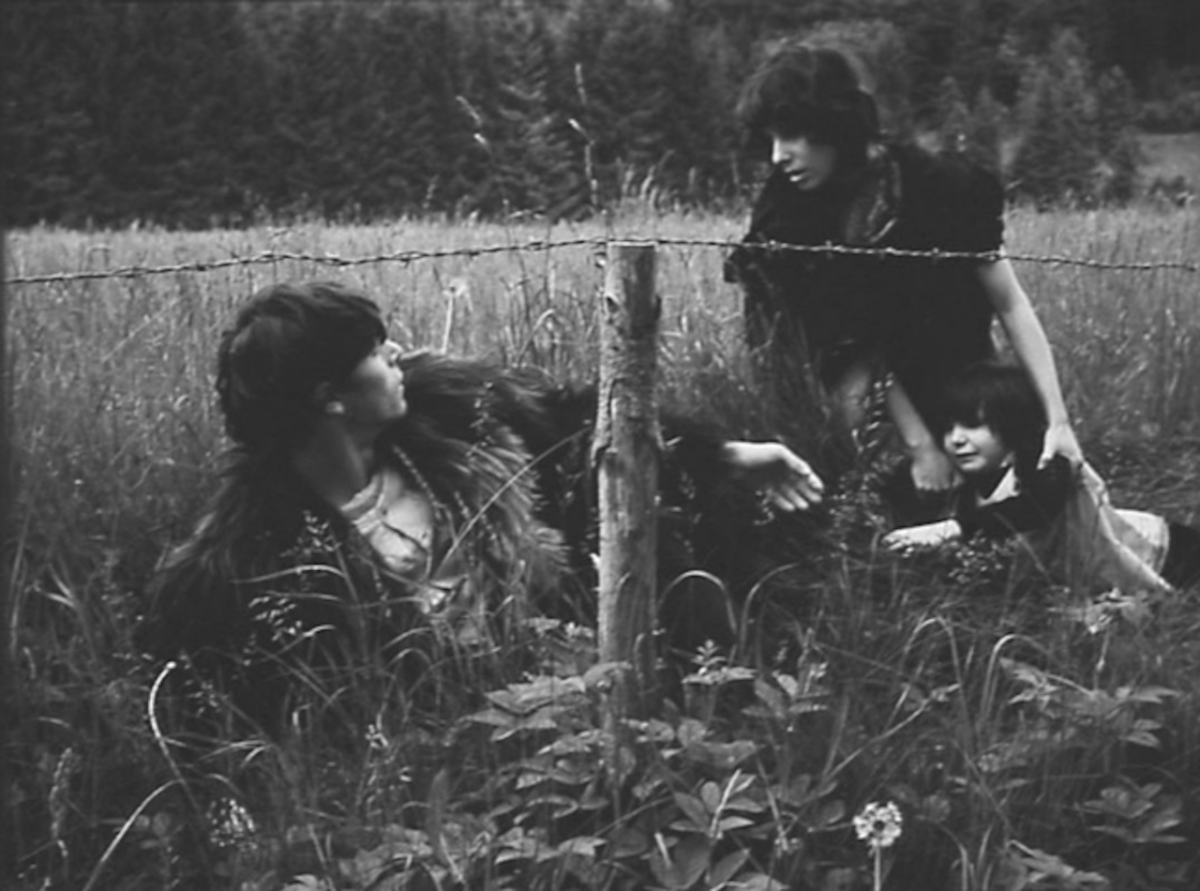

The young parents and their child are searching for how to deal with each other in times of despair and isolation. Spatially far removed from the May ’68 revolution in Paris—they are on the run and their escape is staged in German landscapes dotted with military bases—it is unclear whether the parents are fleeing from the state (the invisible enemy), or actually from the child. The trio seems to dive for cover against invisible gunshots, but actually the war is being waged both external and internal. The child seems like a great weight on the parents’ shoulders, which they are both forced to bear. Occasionally they leave him behind and occasionally they carry him on, crawling through the tall grass in which they are hidden, where nothing or no one can be seen, only the waves of the grass set in motion by their movement indicating their presence. Although the child initially seemed to have come to break the impasse of the relationship between the man and the woman, it becomes increasingly clear that his existence fails to do so and becomes a new impasse itself.

Interestingly, Garrel puts thematic and formal directorial cues in the child’s hands. The boy stands before his parents, deciding what to do with these ghosts who clearly, but apparently unwillingly, seem to be attached to him. He hands them coats, walks by the camera to give his teddy bear to someone behind the camera and directs the movements of the mother and the father by taking their hand and pulling them along the road, leading the way. The boy breaks the fourth wall not only when he gives his teddy bear to a member of the crew, but also in a different sequence when he looks piercingly into the camera and uses his hand to direct the pan movement of the camera, which it dutifully carries out.

That the little boy almost functions as a director in the film is also visualized in the scene where the parents argue about him on a stage. He gets down from the podium, takes a seat and the curtains open. On stage, his mother enters trough one door and his father through the other. The only one who is watching from the auditorium is the boy, as if the actors and the director are doing one last run-through before the play premieres. The parents start fighting and point at the child. It conjures up the feeling when, as a child, you lie in bed at night and hear your parents arguing about you. You stiffen up and can do nothing but listen compulsively, even though you don’t want to hear what they say. This scene is also a striking visualization of the child’s neglect throughout the film. The parents’ argument about the child is literally staged before his eyes; a true mise-en-scène de la solitude.

The child’s loneliness is also palpable in the moments before he goes to sleep. Just before he lays down, he runs a few laps around his parents. It seems as if he wants to tie them down and can only find peace when he is sure they will not leave him behind. (At the same time, and contradictorily, he seems to feel best when he is alone, because those are the only times we see him behaving like a normal playing child, with a colander on his head or a spray can in his hand.) The circling at bedtime does not only involve the child: the mother also circles the child and the father, and the father also circles the child and the mother. The conventional outward physical gestures between child and parents are subverted and reconsidered in Le Révélateur.

The film’s oneiric structure, its return to the primitive period of cinema, and its strong surrealistic, affective play on the viewer’s senses and nervous system, makes the viewing experience eminently physical. But during this bodily experience we are shown characters that almost deny the corporal reality of being. The blending of the alienation of Brecht’s Verfremdungseffekt and the sensory affect theory of Deleuze’s Cinema du corps, makes Le Révélateur almost psychedelic. In Cinema II, Deleuze argues that cinema can realize the inherent potential of art to act directly on the nervous system, not through depictions and representations, but through vibrations and affects; not to initiate thought but corporeal and subconscious activity. With minimal props, by breaking the fourth wall, abandoning a linear and causal logic, keeping the location of the sequences unclear and making illogical spatial changes, Garrel, in the spirit of Brecht, makes it very clear that it is cinema that the spectator is seeing and not something that pretends to mimic reality. Just as the conventional outward gestures between child and parents are subverted and reconsidered, these formal interventions break the automatism of the viewer’s perception and enables them to grasp reality in a new way.

Garrel subverts all kinds of structure with his film. In this sense, the fact that Le Révélateur is a silent film is not merely a throwback to primitive cinema. Garrel literally silences any form of language as we know it in the world outside the cinema auditorium. The film’s silence is not a symptom of the inability of speech, but of a language in which speech is absent. Its absurdity lies precisely in the complete omission of the conventional bodily and spoken language that structures the world around us, but also shapes it. Ludwig Wittgenstein said: “The limits of my language means the limits of my world.” Language is a tool to shape and structure the world and it determines what one (can) think of the world. It is impossible to speak about that which cannot be expressed. If we don’t know the words to express something we think or feel, and it only exists in your unconscious self, is it real?

Le Révélateur refers to life before it is defined by conventional language, irrevocably linked to being a child, and invents a new kind of language, one that is unfamiliar, a language that is not used for the sole goal of communicating and assemblage of the world. The language of Le Révélateur is almost like a pantomime that did not originate from a verbal perspective on reality, that isn’t determined by conventional spoken and bodily language. A new pantomime in which the whole process of defining the world has taken a completely different course. A new kind of language also means a new kind of reality.

Federico Fellini once pointed out: “A different language is a different vision of life.” With its own language, Le Révélateur unfolds a new world and a new reality. A world that resembles the world we experience when we dream; a fragmented world, a world that may exist in the same context, but one that in its execution resembles nothing we know. Watching Le Révélateur is surrendering to the images of our being, when they are not determined by seeing the reality around us. Its language sails on the cadence of sensations and affects before they are determined by words and ordered into a sentence. It is a metaphysical search for ways of being, in which the spectator becomes one with their body and their senses without being able to give a linguistic explanation as to why they feel a certain feeling. It is in the collision of images and the spectating body that Le Révélateur exists. The film accrues meaning in its bodily reception, but in the visual language Garrel invents, the body is a burden, something to be forgotten and denied, rather than an instrument. This makes Le Révélateur simultaneously sensuous and nonsensuous cinema.

Le Révélateur is a poem of bodies that are lonely within their proximity. A poem of fragmentation that returns to the essence of cinema. It nestles itself in our being. We find the rhythm; or the rhythm finds us, puts our senses under high tension and, just as when we go to sleep, takes us on an uncontrollable journey in which we leave our own consciousness behind. Le Révélateur is a temporary confluence of imagination and fragmentation that takes place somewhere between the screen and your seat in the cinema.