If he just repeats himself, how can that be sincere?

Let nothing be changed and all be different.

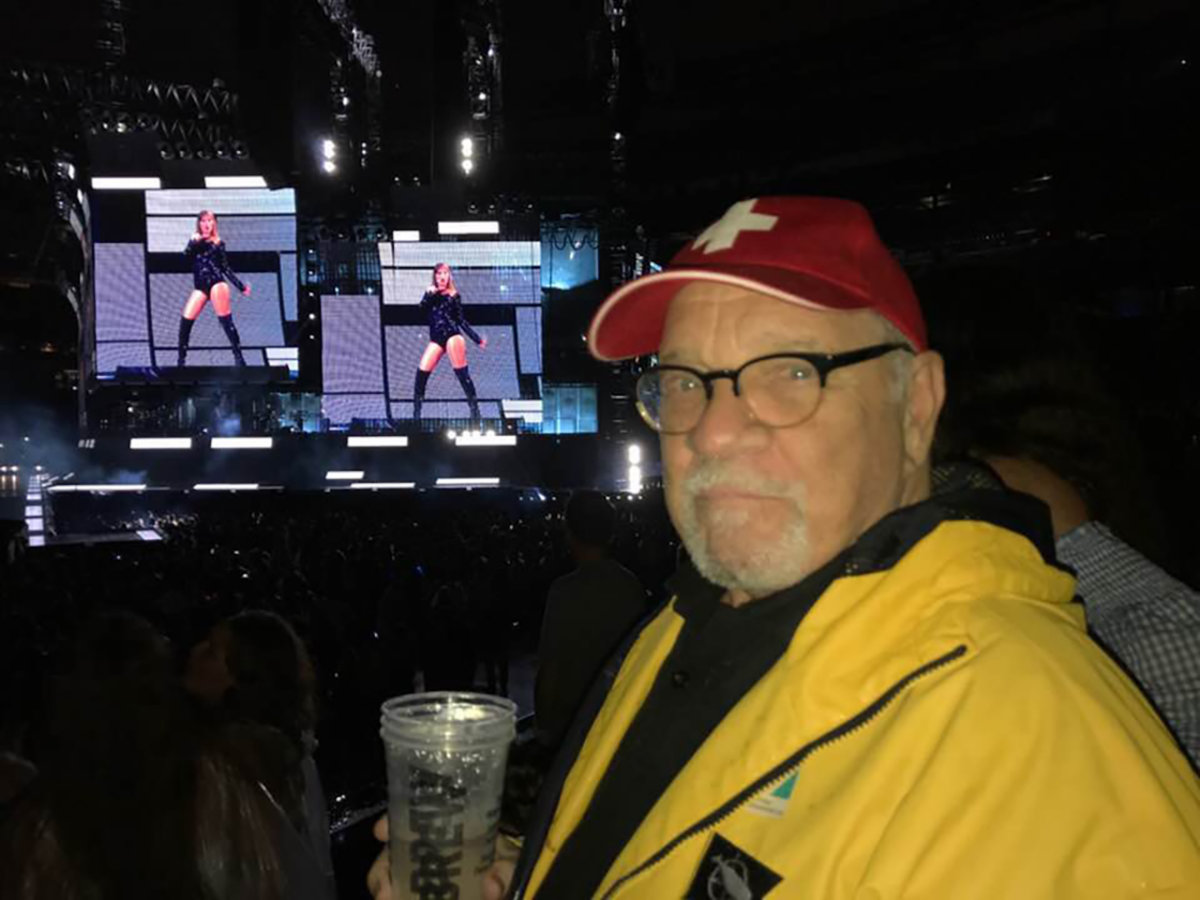

Paul Schrader and Hong Sang-soo have the privileged ability to put butts in seats across the festival circuit, and both released new films in 2022 to considerable fanfare, in a relative sense, as they have accumulated a strong enough cadre of admirers who will always venture out to see their new work. They come from different generations but have amassed a similar number of features due to Hong’s breakneck pace, Schrader only able to release two films in consecutive years in 2021 and ‘22 for the first time since speeding out of the gate in 1978, ‘79, and ‘80. These are two very divergent filmmakers with regards to their subject matter, but they share an odd quality: they’re two of the most repetitive directors cinema has ever seen. They constantly return to the same formal patterns, pet themes, plot constructions, and narrative shapes in an incredibly blunt manner. The famous Renoir maxim of “a director makes only one movie in his life, then he breaks it up and makes it again” maps itself prodigiously well onto their filmographies, but Hong and Schrader almost dull the poeticism of this idea, crafting films so headstrong in their self-citations that it creates unique effects, and reveals the distinctive quality of their personal ideas of cinema.

The most apparent repetition in Schrader and Hong’s films is a foundational feature of their filmographies. Both directors have what can be considered a trademark shot composition, essentially a signifier of whose film you’re watching. If you know you know, these shots can even prompt laughter from the informed viewer’s recognition; for Hong, the eye-level medium shot at a table decorated with bottles of beer, soju, or makgeolli where two or more people are sitting across from each other is as good an indication you are watching a Hong Sang-soo film as his name in a “Directed By” credit. For Schrader, there is almost always a man sitting at a desk, the room ascetically sparse as he writes in a diary usually alongside a glass of brown liquor, with his writing communicated in voiceover.

These shots make their way into each director’s films in different manners. Schrader weds his film entirely to his protagonist, preferring a certain classical narrative shape occurring within and around his “man in the room” as he stoically goes about his business. Hong builds repetition into the structure of his films, they are chock full of doublings, variations on an encounter, people returning to the same urges over and over again to a comic extent. His characters are always a smorgasbord of artistic or intellectual types: professors, filmmakers, painters, actors, novelists, poets, and art students making up nearly all of Hong’s universe. Hong works with the same people, there is an intrinsic “pleasure of the stock company” aspect that comes of an acquaintance with his films, the repeated visages of Kim Min-hee, Kwon Hae-hyo, Seo Young-hwa, and Ki Joo-bong, just to name a few, add to the sense of a familiar world being returned to over and over again.

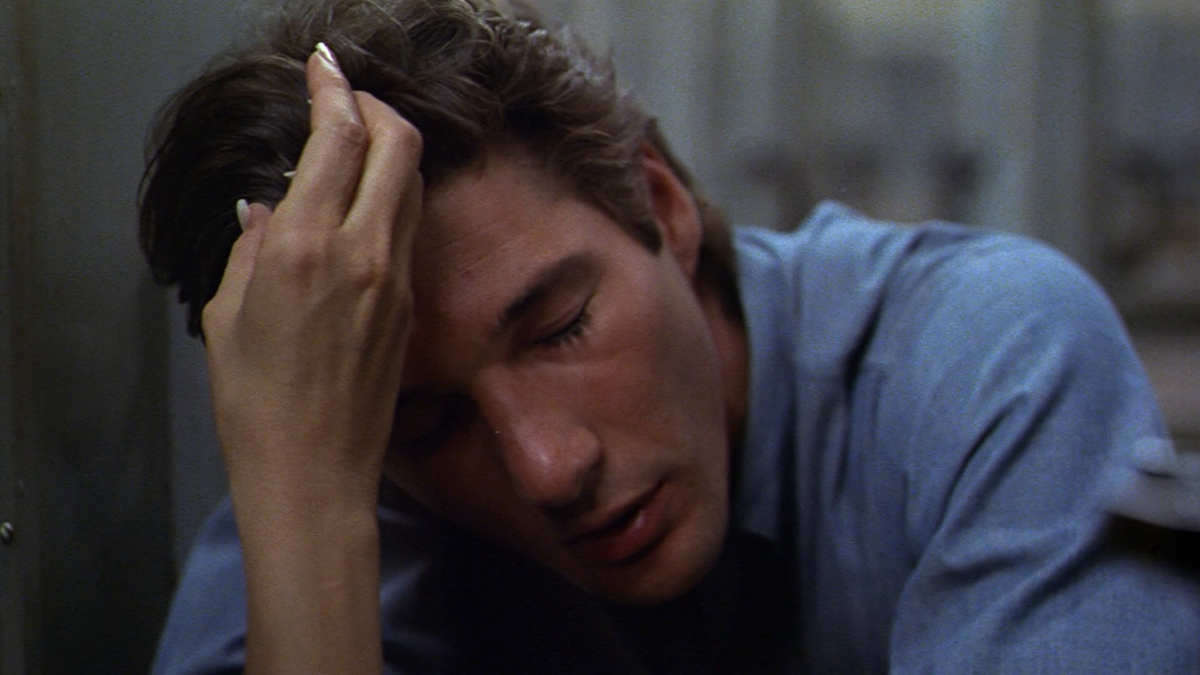

Schrader works with a myriad of genuine Hollywood stars, from Richard Gere to Oscar Issac, but always within a similar milieu; whether in a major city like the NYC of Light Sleeper (1992) and the LA of American Gigolo (1980), or the rural small towns like the Upstate New York of First Reformed (2017) or the New Hampshire of Affliction (1997), his worlds are decidedly lonely places, populated only to the extent that it reflects the protagonist’s psychology. Hong’s recurrent cafes, parks, and apartments, are similarly transitory, purgatorial spaces, but his process is like an inversion of Schrader’s. In Turning Gate (2002), Woman on the Beach (2006), Hotel by the River (2018), and Walk Up (2022), the settings exist a priori to character, yet exert an immeasurable influence on their thinkings and doings. Hong’s characters are always moving from somewhere. He loves the innate awkwardness of an encounter with an old friend, evinced in films like Woman Is the Future of Man (2004) and duplicated many times over in The Day He Arrives (2011). There is never a defined destination however, oftentimes a Hong film will end, quite literally, right back where it started, even matching the opening and closing shots like in Grass (2018).

Schrader’s lonely men, unbeknownst to themselves, are always moving to something, whether hurtling towards death in the biopic as passion play in Mishima: A Life in Four Chapters (1985), or another of his trademarks, the direct copying of the Pickpocket (1959) ending, as his protagonist ends in jail. The character, having been punished, reaches a type of transcendence, and Schrader returns many times to the final shot of Pickpocket, where Martin LaSalle and Marika Green touch hands from different sides of freedom. This compulsion began with American Gigolo, and has appeared in both of his most recent films, The Card Counter (2021) and Master Gardener (2022).

There is an innate danger to this kind of repetition, especially when it is so recognizable to anyone who has seen more than one film by each author. Hong could be criticized, for instance, in how he mulishly sticks to what he knows: his cinema is dominated by the insular world of artistic mental weather, their creative hang ups placed alongside their more fungible ideas about attachment, love, romance, and relationships in general, with Hong often inserting autofictional elements throughout. To see this as an unambitious venture is to misunderstand the breadth of Hong’s project. He is always traversing forking roads where the paths not taken remain of interest, skirting his character’s inward-looking natures by dissolving through different realities and delving into duplicating subjectivities. 2017’s On the Beach at Night Alone shares a title with a Whitman poem, where Whitman posits a world, or universe rather, in which “a vast similitude interlocks all”, and Hong’s affinity with this idea presents itself constantly in the repetitions of his structures. The diptychs in Right Now, Wrong Then (2015) or Virgin Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors (2000), the loopings of The Day He Arrives or Oki’s Movie (2010), or the elusive, scattered chronologies of Hill of Freedom (2014) or Walk Up are fractal in the most confounding ways, to the point where even describing Hong as repetitive can feel trite.

However, Hong and Whitman are not perfect artistic bedfellows, the scattered symbolic meanings of a Whitman poem always point to something of metaphorical importance to the overall design, while Hong remains more slippery in this regard. He will disperse these supposedly meaning-charged signs throughout his films, think of the thrown up octopus in Oki’s Movie or the stray cat in The Woman Who Ran (2020), but their function is more hieroglyphic, a part of the language with which Hong puts across the conception of his world. There is no lock and key meanings to be found within his films, in fact he seems to relish in being so tricky to get a hold of; even the Whitman allusion in the title of On the Beach at Night Alone feels more like an interpretive tease than anything that feels of particular function to that film. Fritz Lang created webbed network narratives stuffed with symbols and structures of variegated meanings, but his films are like doomsday clocks, obsessed with destiny where the alarm bells always ring and time runs out.

Hong constructs his films in a closer manner to one of Lang’s greatest admirers, Jacques Rivette, a director of reverberative, unsolvable games of chance with mismatching puzzle pieces. In maybe Hong’s most Rivettian sequence, a woman in Grass runs up and down the stairs for what seems to be a long time, varying her pace slightly, and as the action repeats, her expression changes. A previously stony face becomes warmer, and adorned with a smile of some unutterable recognition. The repetitive action acquires meaning in its repetition, but it is an unspoken, ineffable meaning, where the viewer is left to only try and parse it. To think one can lock down interpretation present within a Hong film brings to mind the oft-repeated quote in Tale of Cinema (2005), where an actress tells her sexual companion as they discuss a movie “I don’t think you understood the film”.

Schrader ducks the repetitive dangers of his dedication to “God’s lonely men” as he calls them, through a vigorous belief in fiction. He is Hong’s opposite in that his protagonists come from such a variety of different places and experiences, ranging from Gere’s LA sex worker, to Ken Ogata’s Yukio Mishima, to Oscar Isaac’s Iraq War Veteran turned card player, but they are united in Schrader’s view that these men all share the same ache. It is funny how Schrader as a critic was a professed Kaelite, owing the first break of his career in criticism to a chance meeting with her, and memorializing America’s foremost anti-auteurist in Film Comment by saying things like, “She dominated your thinking” and “Infected your life like a whirlwind”. He wrote wonderfully on the experimental and educational films of Paul Eames, where even with Kael’s infamous poison-penned rebuttal to Andrew Sarris, ‘Circles and Squares’, most likely swirling in his brain, he can still profess: “In all his diversity Eames is one author, and his creation is not a series of separate achievements, but a unified aesthetic with many branch-like manifestations.”

This is not all that far from Schrader’s own project, as his protagonists can be seen as branch-like manifestations of the same person, where Schrader’s “unified aesthetic” doesn’t occur formally, but in the almost naive conviction that these men can be found everywhere, and that their desired path towards salvation is of deep significance to how humans can exist in the world. The repetition is then possibly an admittance of the failure to grasp the scope of such a lofty problem, but returning again to Schrader on Eames: “….in a sense what gives a work of craft its personal style is usually where it failed to solve the problem rather than where it solved it.”

Method and Economy

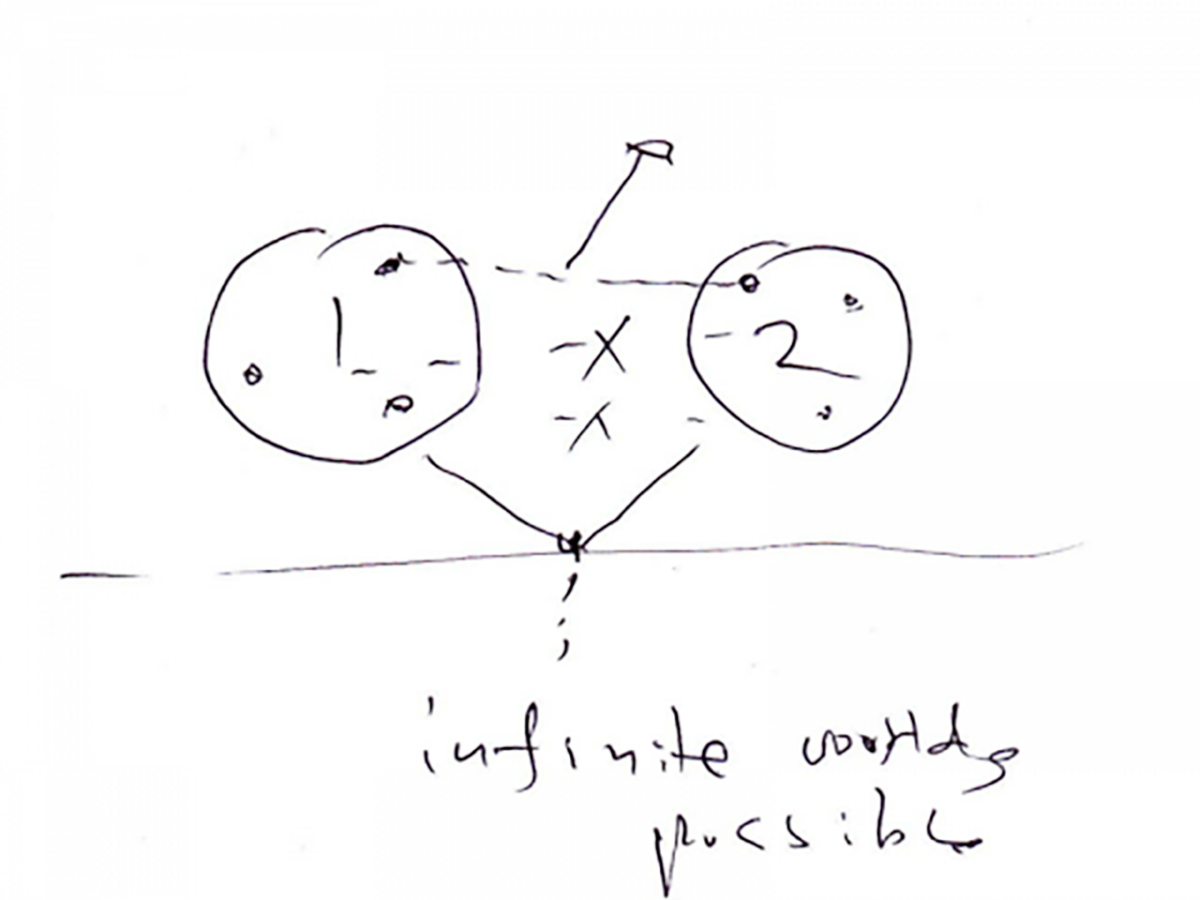

It is worth considering how these directors have been able to be so obstinate in their dedication to repeating themselves, both in the methodological and industrial/economical sense. Hong is infamously skittish about the subject of method, drawing a rather nonsensical diagram when asked about it at one festival, while Schrader is pretty open about his process, his screenwriter bonafides giving concrete answers to the questions people may have. Hong also writes all of his films, but, again rather infamously, scripts them the morning of shooting. This process of scripting would seem to invite improvisation, but Hong demands strict adherence to the words on the page when shooting, it is the performances which give the improvisatory quality that has been often labeled as “realistic” (whatever that means). He is on record as saying “People say I make films about reality. They’re wrong, I make films based on structures I have made up.” This statement, as much as it reveals, also seems to cultivate an authorial myth. Hong’s self-mythologizing functions in the same way as his diagram, which, as in the aforementioned collection of meaningful yet meaningless symbols, he seems to relish in his ability to confound.

What we know for sure about Hong is that he is rarely not in the process of working, a Fassbinderian pace to his filmography is proof enough, and his budgets are remarkably small. His films usually end up around the $100,000 mark, with all profits accumulated going into the next film, probably already in pre-production. Schrader seems to be moving increasingly towards this mode of production. He began down this path with the relative success of First Reformed on a budget of $3.5 million, miniscule in Hollywood terms, and subsequent films The Card Counter and Master Gardener falling somewhere around this number as well. In a talk at NYFF for Master Gardener, Schrader speaks about how these small budgets require a tight shooting schedule. Only three weeks of shooting was done for Master Gardener. Again these numbers are relative to the industry he works in, it is hard to imagine Hong working with a budget of seven figures, and three weeks is probably a long shooting schedule for him, but there is a mutual, cross-continental recognition here that in order for these directors to have such candidly personal work, they must pursue a different way of working.

In recent films beginning with Introduction (2021), Hong has stripped down his crew even more and become his own cinematographer, a move all the more interesting given that his crews were already small to begin with. His partner Kim Min-hee has become even more integral to the production, not just as an actor but now as a production manager, and these newer films have seen Hong evolve somewhat. Introduction, In Front of Your Face (2021), The Novelist’s Film (2022), and Walk Up all seem to have rougher edges, less locations and “bad” cinematography in the film school sense, but accordingly bear some sort of clearer mark of himself within them.

In the aforementioned NYFF talk with Schrader, interviewer Gina Telaroli brings up Max Ophüls, or rather the “Max Opuls” as credited in his Hollywood films, and how working in the dream factory forced him to speed past the things he didn’t care about in order to spend three days perfecting a tracking shot through a house, like in The Reckless Moment (1949). First Reformed sees Schrader at a level of Bressonian composure, composing the film with artful vigor and an intensity he hadn’t shown in his previous work in the 21st century. 2022’s Master Gardener has the appearance of the same glittery, clean design, but beneath it lies a pretty roughly constructed film, with multiple instances of near-amateurish continuity errors or Steadicam moves that feel like take ones. However, it is easy to see where Schrader takes off from Ophüls and spends much more time on certain aspects of the film. His concentration zeroes in when the protagonist played by Joel Edgerton strips and reveals his white supremacist tattoos in a moment during his blossoming love affair with the much younger Quintessa Swindel. In this scene all previous roughness melts away into masterful compositional control as it takes place within a hotel room lit with maximum expressive intensity. It is as if the film exists in order to film this scene.

The Future

The shared awareness both directors have of the particular qualities of the film industry provokes a similar reaction for them, and in their films they give a sense of charting their own terrain, and creating conditions that can allow for their repetitive natures to thrive. They give no indication that the compromises intrinsic within this position are restrictive in any way, instead they become an opportunity, where the margins induce creative fermentation that might not occur otherwise. The 2013 Venice Film Festival had a program of short films entitled Future Reloaded where they asked a variety of filmmakers to make shorts around 90 seconds that in some way presented their conception of the “future of cinema”. Hong’s film is, per usual, pure Hong: a man sits on a bench with someone, presumably his wife, then wanders away to share a cigarette with a younger woman. In the small talk with the other woman, the man brings up his wife’s illness, forcing him to smoke at a distance from her, and the film ends by panning away from the conversation to his wife alone on the bench, coughing. The future of cinema indeed.

Hong is not an artist who doesn’t think about his place within the industry, his many filmmaker characters always complain of constant festival appearances, lack of money, and producers who will never understand true artistic vision; but it is telling that Hong simply stages an encounter when asked to address such a gigantic question. In its brazen reticence towards addressing the requested subject, it reveals what he really believes is the future of cinema. Hong’s idea is that if things are so shitty for cinema right now, the response is to go smaller, burrow into oneself and become more stubborn, reject the bloat present in both the multiplex and film festivals, and consider your apparently “minor” films as your primary form of opposition. Manny Farber’s white elephant/termite art dichotomy is often completely misunderstood nowadays, but we live in an era of the most artless elephants ever put to movie (or phone) screens. Hong’s response is to stay in a minor key, like Flaubert said in a letter: “there is no such thing as a fine subject” and “one can write equally well about anything at all. It is the artist who elevates things.” To bring back Fassbinder, he often spoke of building a house with his filmography, and while Hong maintains his pace, therefore having enough plywood, he prefers to keep remodeling the basement.

As mentioned before, Schrader seems to be moving somewhat in this direction, even while maintaining what could be considered “elephantine” themes, and his own entry into the Future Reloaded series sheds some light on his slight divergence from Hong in this respect. His film is quite possibly his magnum opus, the ultimate “Man in the room” film, where Schrader himself dons a Doctor Octopus style apparatus, its various arms ornamented with Go-Pros, as he takes a stroll on the High Line in NYC donning a neon green helmet. “Motion pictures are again in a time of crisis” he exclaims—it is worth nothing the wonderful nasally timbre of his voice, key to the film’s effects—as he makes a distinction between the socially determined crisis of cinema resulting from the tumultuous cultural conditions around the New Hollywood era, and the technological crisis emerging in the present day, speaking of how “we don’t know quite what movies are”. Schrader’s critical writings about the noir and Yakuza genres had similar conclusions present here, where he posited that these generic forms were cinema’s way of responding to particular conditions of the time period. This implies a belief in cinema’s unique dexterity at being able to react and, in better ways that other art forms, address The Things That Are Happening.

It is forever fascinating that for directors of Schrader’s generation, the New Hollywood brats like Spielberg, Lucas, Coppola, Scorsese and so on, Schrader is the only one who continuously films the present day, and with a digital camera. Even those from the generation right after, Tarentino, James Gray, and Paul Thomas Anderson are all celluloid fetishists who cannot stop running backwards into the past, for Gray and Spielberg this year, literally into their own childhoods. Not to completely denigrate the ventures into the past by these directors, but they’re all well aware of cinema’s diminishing place within the culture at large, and to consistently retreat backwards points to a fear that Schrader doesn’t share. Instead he seems pissed off. Films like First Reformed and The Card Counter quake with existential fury about the questions most American directors skirt past, be it the impending environmental crisis or the horrific war crimes committed by America in Abu-Ghraib. Schrader diverts from Hong in this respect, Hong avoids direct socio political questions in his films, but both share the same sense of fighting for something, rather than retreating into something. Schrader has mentioned a comment he made to Scorsese when discussing the preservation of classic cinema: “Why should we preserve film if we can’t preserve the people who are gonna watch it”. His fear is more directed at the doom-laden future, his repetitions the same screams into the void of his protagonists.

The Artist and Everyone Else

Like Schrader said to Scorsese, the troubling thing about movies, about art, is that there must exist a group of people willing to dish out the cash to sit down and try to respond to them. There is an Albert Camus story called ‘The Artist at Work’, where one of the characters is lying on his deathbed, and as he dies the people around him become confused as to what his last word was, either “solitaire” (solitary) or “solidaire” (solidary). This is the bind that comes with being so bullish in your indulgent repetitions, you risk only talking to yourself, aloof from other people, and away from a viewing public. This desperate reach towards other people is a question that preoccupies the cinema of both directors. Hong’s cinema is a conversational one, always steeped in the awkwardness of speech colliding with passions, desires, or thoughts, causing the stop and start nature of his small talk that in a moment’s notice will bloom into intense, deep conversation. “Hell is other people” says the Sartre of No Exit, but even with the sense of primal misunderstanding present in Hong’s films, he most likely prefers the theorist Lauren Berlant’s formulation of Sartre’s iconic line: “Hell is other people, if you’re lucky.” Like Camus’ artist, Hong’s characters are always circling the spaces between their ears, they’re constantly lonely, adrift, tormented by nagging questions about their art, their lives; and you get the sense that without sitting down and having four bottles of soju with a group of friends, they would fall into a despair too deep to climb out of, suicide being a consistent specter in Hong’s world. It is not so trite as a hackneyed celebration of the pleasure of human interaction, but Hong knows that it is something that literally every single person shares, and it is the starting point from where he pushes the record button.

Schrader’s protagonists exist in the liminal space of waiting to be saved, and in their stoicism, their competence at their jobs, their routine exercises of control over their lives, have a kind of romantic, artist-like disposition towards their way of living. They look at the cruel world with puzzlement but enduring observational curiosity; something to be dealt with in due time, but always by themselves. At the end of Affliction, to explain Nolte’s actions, his brother played by Willem Defoe explains that he is a type of man “who’s best hope for connection with other human beings lay in detachment, as if life were over”. Nolte dies at the end of that film, burning his childhood house down with him and his father in it, as his small town eventually transforms into a chic resort ski town for yuppies from the city. It’s a vision of salvation never found, harrowing and empty in its assertions. There are often jokes made about Schrader’s continuous return to the Pickpocket ending, some calling it lazy or always unearned, but what is beautiful about it, is that it is cinema’s iconic image of salvation, and Schrader sees it as so multivalent that there are a million paths towards it. What always saves a Schrader character is human connection, and the hands touching is a complete and purified image of resistance against a world that wants to atomize its inhabitants to oblivion. Camus’ artist at work leaves the nagging “art vs. the whole world” question ambiguous, while Schrader and Hong hysterically try to make it as clear as possible, repeatedly.

The simple syrup of contemporary culture delights in drab uniformity, and a world decorated with gray laminate wood flooring has found its perfect echo in the netflixified greenish-brownish underlit slop that is thrust in front of people’s eyes when they sit down in front of a screen. While their repetitions angle themselves into their filmographies differently, and they certainly have different ideas which guide their films, Hong and Schrader are examples of artists who cannot help but throw every bit of themselves into their work. To consider their point of view is to be willing to be a bit more generous, recognize that while they will never show you certain things, they will repeatedly show you something you cannot get anywhere else.

A different type of viewing emerges, a viewer well acquainted with their work becomes more creative, even athletic, dealing with the film using a double consciousness: both in isolation and as a constantly evolving, recontextualizing whole. This is not a game of “spot the difference” but something infinitely more generous, accepting quirks and “errors” as virtuous, products of an imperfect person returning to the things which will forever nag at them. It is understandable to think as if these are artists who never progress, who will always be filming the same cafes, or the same lonely apartments, but, to use a rather capitalistic analogy, why does a company have to grow? The films made by committee that swallow up cultural, economic, and physical space flatten the human out of the art, and Hong and Schrader present two examples of artists built to resist this exact assault; a name in the credits isn’t enough.

Something special happens when engaging with multiple of Hong’s or Schrader’s films. One starts to see a physiognomy emerge, where the physical person reveals itself through the collection of images and sounds, both in their most annoying tics and most beautiful ideas. The repetitions then become exhortations to be received, a challenge to be accepted, and hopefully, to be valued.