The idea of pure, absolute expression is dead; it only temporarily survives in parodic form as long as our other enemies survive.

Guy Debord & Gil J. Wolman, ‘A User’s Guide to Détournement’

Film was of particular importance to the Situationists because of its potential for subversion. To steal, to borrow, to appropriate—to reclaim—pre-existing material are necessary actions that need to be taken against an art that has become stale and commodified. To rework and to remake are acts of resistance.

In the situationist practice of détournement there is an underlying nuance of proactive, revolutionary violence. You detourn an object or a work of art like you might hijack a car. Alternatively, a détournement is an act of sabotage, aiming to dismantle prestige and authority by investing ‘bad books’ and that which has slipped through the cracks of cultural history with new, potent meanings, often with the “extensive (unintended) participation of their unknown authors”Guy Debord & Gil J. Wolman, ‘A User’s Guide to Détournement’, 1956; http://library.nothingness.org/articles/SI/en/display/3. A martial arts film no one has ever heard of can easily become an impish agitprop satire. ‘A film produced by the person listed here, who naturally has no idea what happened to his film’ is the nonchalant and overt declaration in the detourned opening montage of René Viénet’s La dialectique peut-elle casser des briques? / Can Dialectics Break Bricks? (1973), setting the tone for one of the funniest and certainly the most approachable theoretical films made by the Situationists.

Alienated vs. Bureaucrat

While Viénet is often celebrated as one of the only two filmmakers in the Situationist International (the other being Debord), his films were made and released after he had parted ways with the group. By 1973 the SI had also altogether already disbanded. Nonetheless, La dialectique peut-elle casser des briques? still adheres strongly to situationist principles, qualifying, in fact, as one of the few situationist films per se that were actually ever made.

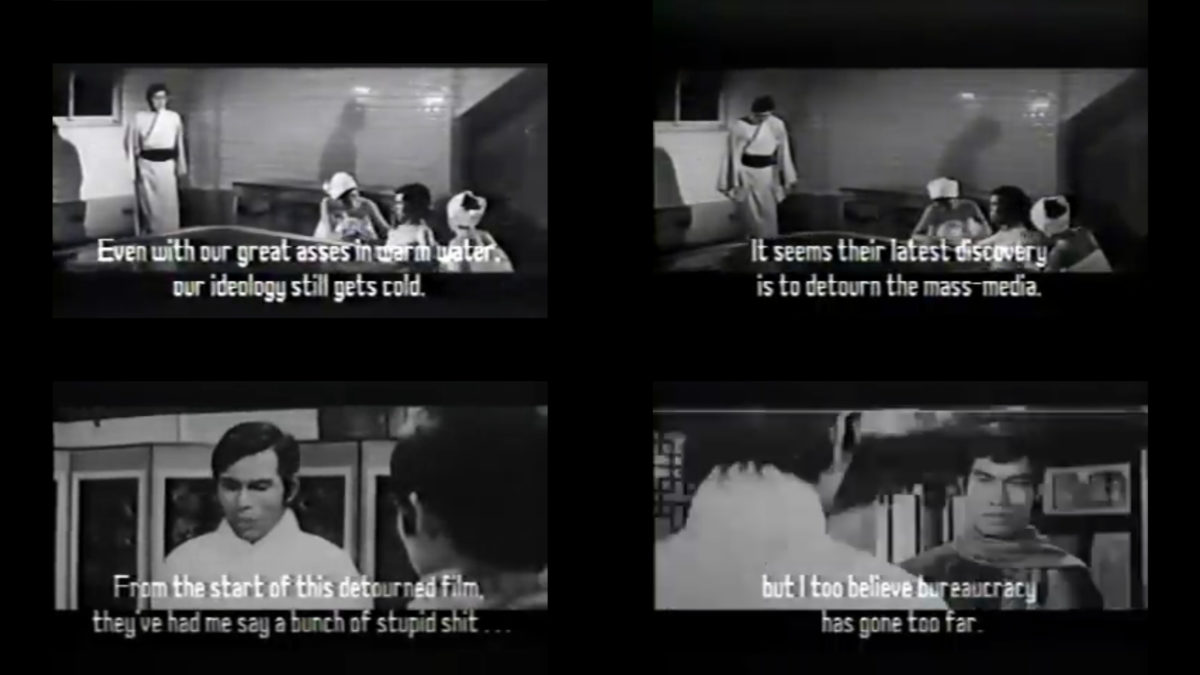

Viénet, also a sinologist and a great fan of Chinese and Hong Kong cinema, had previously bought the rights for an obscure martial arts film, a Hong Kong feature from 1972 by the name of Crush (Tang shou tai quan dao, dir. Tu Guangqi). Through a very economical but ultimately very efficient use of ironic, absurd and politically charged subtitles, which were later dubbed over the original Chinese dialogueTo note, La dialectique peut-elle casser des briques? had a previous, now-lost first version consisting only of subtitles over Chinese dialogue. Based on the subtitles, under the direction of Gérard Cohen, a dubbing specialist, the film was later dubbed into the version now most commonly known. More about the various versions of the film can be found in Keith Sanborn’s notes on his translation of the subtitles, http://www.lightindustry.org/dialectics. Also noteworthy is that the film is currently circulating in both a black-and-white version and a colour one. The colour version is, so to say, ‘truer’ to the original one., La dialectique projects a tongue-in-cheek exercise of situationist theory about spectacle and alienation onto an original story about martial artists resisting Japanese rule in Korea. The film also acts as a sum of topical debates happening within the French Left around the year 1970, from a critique of Maoism to sexual liberation or to the failures and disillusionment of Parisian intellectuals and politics in the aftermath of May ‘68. In Viénet’s détournement, the martial artists become alienated individuals that have awoken to the realisation that they are being exploited, and the Japanese officials become the bureaucrats of state capitalism trying to coerce them into the system and into a now ‘cold ideology’ of corrupted slogans (‘Work is freedom!’).

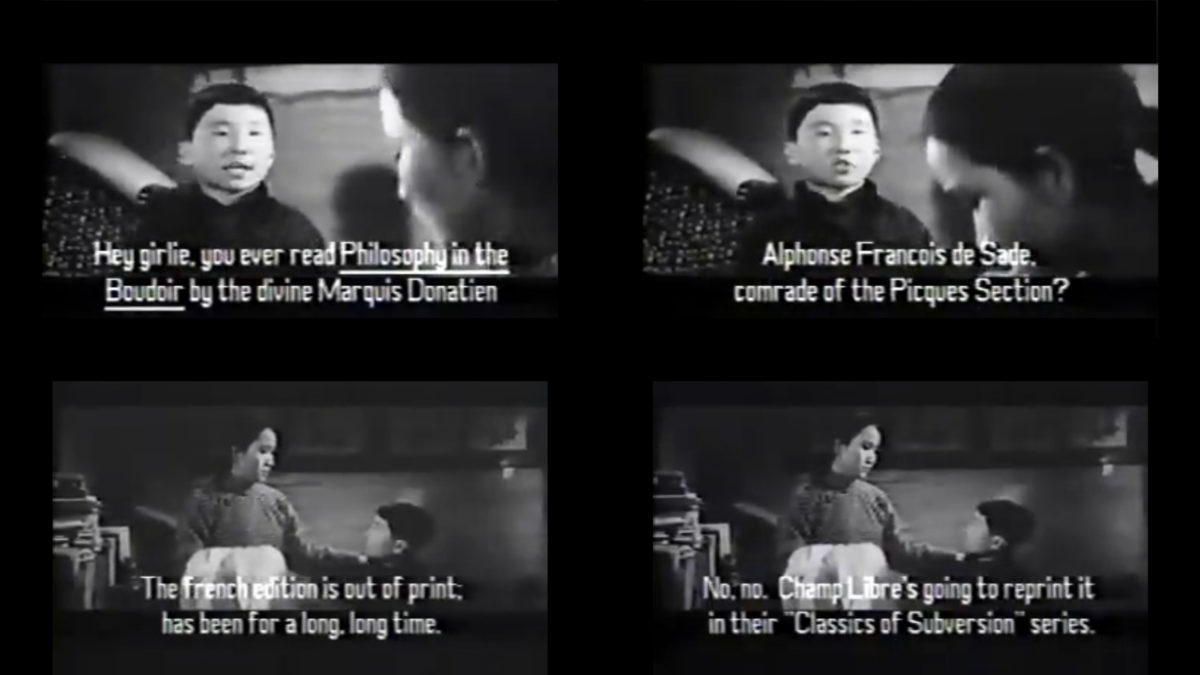

La dialectique’s parodic intent is twofold. First, it functions as a self-deprecating fabula of the French political climate at the time, making inside jokes and digs at movements such as the Programme commun or the PSU (Parti Socialiste Unifié). There’s a sense of distinct contemporaneity in the characters’ inflamed leftist, revolutionary and situationist jargon, going anywhere from a simple ‘comrade’ to overt provocation, instigating to wildcat strikes and to seizing (and detourning) media channels. The ‘alienated’ talk as if they are radicals or students on the streets of Paris and are casually named Nicholas or ‘that-jerk’ Jean-Daniel, with references to essential texts aplenty, including those of Marx, Wilhelm Reich, and Debord himself. “For this sequence, consult Enragés and Situs in the Occupations Movement, in the Gallimard edition, pages 207 and 231” a sly voice-over asks of us. La dialectique’s sublime hilarity comes, in part, from Viénet’s acknowledged provovations—he is overwhelming the viewer with situationist references and mocking leftist fashions (the film is produced by the comically lengthy named Association pour le développement de la lutte de classe et de la propagation du matérialisme dialectique)—but also from the unexpected heightened political awareness of its characters. That which is exaggerated in La dialectique shows, conversely, what its source lacks. Little boys asking older women if they have read de Sade may be funny exactly because of the greater, real absurdity, where the original film, as much as the industry itself, are devoid of any political awareness.

Viénet’s reappropriation of Crush further critiques the idea of spectacle and film as a spectacular medium, consistently impending narrative identification through voice-overs or lines that break cinematic illusion and ridicule the visual language of cinema. The opening montage will comment on the original main actor—”He looks like a jerk, it’s true, but it’s not his fault. It’s the producers’”—or characters will mention that they shouldn’t worry about the conflict not being resolved so early in the story. This metacinematic discourse constantly draws attention to the ridiculousness of genre tropes and subverts their meaning—as happens, for example, in a last fighting scene where the voice-over cheekily points out that it’s easy to guess that the character dressed in red (obviously the proletarian) might win. Touches of crude and vernacular language—the alienated are termed ‘prolos’ [proles] by the bureaucrats and all constantly remark on the ‘connerie’ [bullshit] that is happening—also break the spell of prestige and subvert the tone of the original film into a low-brow, irreverent comedy. The repetition of sex jokes, sneaked in with the attached academic references to texts about sexual equality and liberation, contribute to the crudeness, as much as to a subversion of the fact that the typical martial arts hero usually leads a sexless life.

Even though all the references and the words used in the film feel completely congruous with situationist terminology, it must be pointed out that Viénet’s strategies for dubbing and subtitling strike as particularly different from other instances of détournement. In The Society of the Spectacle (the film version coming out the same year as La dialectique), Debord hijacked the audio tracks of its sources away from their initial narrative and spectacular intent and replaced them with a parallel, detached, voice-over commentary, lifted from his own writings. In contrast, Viénet’s approach preserves a palpable relationship with the source material, where the subtitles try to match the film and engage with what is happening in the frame, creating a fake, detourned narrative. This is another source of the comical absurdity: the film plays on the default supposition that subtitling and dubbing are practices which facilitate understanding and which should seek fidelity, yet, evidently, in this case, words are actually being put into the characters’ mouths. In doing this, Viénet lends authority to a system that is otherwise seen as ancillary to film, challenging what a subtitle or a dub should normally do. From mere facilitators, they become active parts in the creative process.

La dialectique also plays on the fact that martial arts films are inherently tied to dubbing, both in terms of local production—a film will most often also be dubbed in either Mandarin or Cantonese to reach all local audiences—and in terms of international reception. The kung fu craze, which had already reached its height in the West during the early 1970s, has famously birthed many cheap and hilariously faulty dubs and subtitles, a symptom of a greater problem stemming from their intensive commodification in a transnational context. To some extent, La dialectique also hijacks the average Western spectatorship experience of a martial arts film, in the sense that a Western viewer has most commonly encountered this kind of films through their (English) dubbed version.

Aside from the subtitles and the dubbing, Viénet’s interventions on the actual filmed material are otherwise curiously minimal. Scenes are rearranged so as to better highlight the story of the villainous bureaucrats—for instance, the Japanese officials wallowing in the bourgeois comfort of a bathhouse are shifted earlier in the timeline. However, there are no extensive additional cuts being made within the scenes themselves, with the film coming out at roughly the same playing length of its original. “The first entirely detourned film in the history of cinema”, announces La dialectique in the beginning. Viénet bases his remaking on one single and integral film, whereas other situationist détournements, such as the aforementioned The Society of the Spectacle, have resorted, pardon the topical bricks reference, to a bricolage of various sources and limited excerpts from feature films. But how exactly does Viénet’s film interact with its source material as a martial arts film?

Young Proletarian, Seen Through Bamboo

The martial arts genre finds itself in a bit of a contradictory position as to what commentary might come out of its détournement. On the one hand, at the height of its economic success and popularity, these films could be considered the prime commodity of the Chinese and Hong Kong film industries, a very lucrative and repetitive genre that bases itself on exploitative and cheap, assembly line-like spectacle meant to numb and brutalise the masses. On the other hand, if it might be safe to say of the subgenre of wuxia, with its legendary sceneries and supernatural inserts, that it promotes escapism and distracts the audience’s attention from political consciousness, the kung fu film in particular still retains some proletarian nuance. More than the discussions about realism and fighting techniques, kung fu films often feature stories about the common man opposing systems or oppression, consistently building up a communal understanding of that mission. In its reception in the West, the genre has equally been one of cinemas on the fringe and of grindhouses, and has held high appeal to marginalised and underrepresented groups and communities. If understood as part of a low-brow and peripheral popular culture, the martial arts films could equally be seen as a chance to liberate the masses from the hegemonic culture of prestigious art and cinema, and, furthermore, from the hegemonic Western-centred tendencies of their canons. Despite its ties to a capitalistic system of industrial film production and despite its engagement with visual spectacle, it is worth asking whether the martial arts film, and specifically Crush’s generic kin, the kung fu film, may have been the spectacle par excellence that the situationists had it out for.

Perhaps, as the corollary dialectical materialism that is mentioned throughout La dialectique may have it, Viénet, as a sinologist, was very aware of these contradictions when he made the film. The original story of Crush may have been a very fertile ground to detourn because it already contained tensions between classes and ideologies. They just had to be brought to the surface and blown out.

La dialectique ultimately doesn’t seem to discard its source as inherently naive or flat-out worthless, despite its adherence to spectacle. The parodic element comes more from the strata that are added through the dialogue rather than from a simple mocking of the source. This approach is something which adheres to Debord’s considerations that detournément should detach itself from the original and reach a “serious parodic stage”“It is therefore necessary to conceive of a parodic serious stage where the accumulation of detourned elements, far from aiming at arousing indignation or laughter by alluding to some original work, will express our indifference toward a meaningless and forgotten original, and concern itself with rendering a certain sublimity”. Guy Debord & Gil J. Wolman, ‘A User’s Guide to Détournement’.. Adding even more to the contradiction, Viénet’s act of détournement also becomes one of salvaging, as often happens with works of reappropriation. Crush is crucially an obscure film that still remains largely inaccessible, rendered somewhat accessible solely through La dialectique. Ironically enough, Tu Guangqi’s film can now be found on YouTube, but unsubtitled, making Viénet’s version currently the closest intermediation of the film for an audience that does not speak Mandarin.

Et maintenant?

Vienet’s caustic exercise may have lost immediate relevance in terms of topical political combats and grudges, but it still resonates with the current (digital) trends of consuming and interacting with media. What La dialectique may further say about authorship, originality, and theft or plagiarism can easily be extrapolated to the practices of reappropriation and remixing that are embedded in the digital language of today. The re-dubbing proposed by Vienet’s film has also survived well in terms of the ‘mock dubs’, the ‘gag dubs’ and the ‘fandubs’ that have been circulating around over the past few decades, although hardly with the same political (see revolutionary) consciousness and edge. Notably, few of these dubs have ever also ventured into long formats, with the exception of perhaps Michel Hazanavicius’ conspicuously titled Le Grand Détournement / La Classe américaine (1993). The situationist aspiration for enlightening, agitprop parody has overall been seemingly replaced by a comedy of bite-sized fleeting distractions. Yet one has to wonder if, in fact, the parodic and very often crude abridged series or fandubs of anime, for example, do not actually provide some intrinsic comment on network driven censorship or on the fact that the respective original products or translations are so often very poorly and hastily done as a result of reification and of the fast-paced demands of a capitalistic market—where anime and popular media are profitable fads, much like how kung fu films were treated during the ‘70s. Could these fan-dubs also not be an act of reclaiming power and cultural products similar in spirit to that of Viénet’s? Is this not one of the more fortunate symptoms of today’s increased democratisation of editing tools and availability of media? Maybe there actually still is much hope for détournement today.