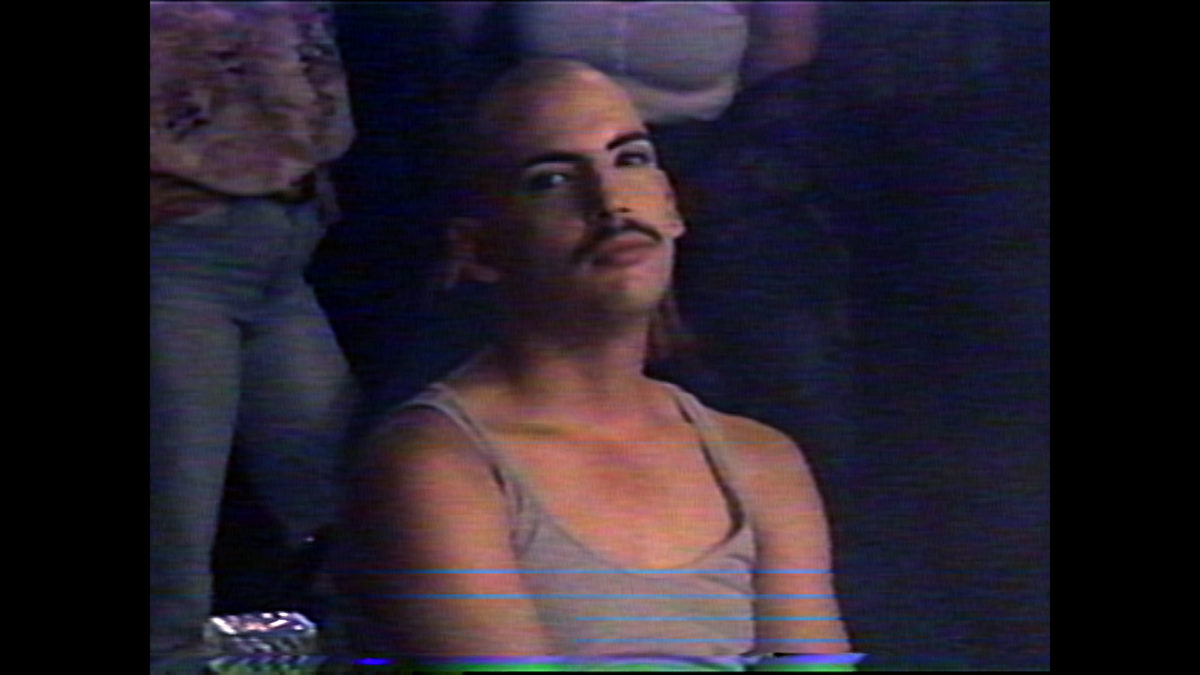

Early in Playback: Ensayo de una despedida (Agustina Comedi, 2019), successive videotape images depict a small group of smiling drag queens in a cramped dressing room, as the narrator introduces them: “this is La Colo, this is me, La Delpi, and this is La Gallega”. They are called the Kalas group. A short, intriguing scene follows with a strongly backlit La Gallega climbing up a set of stairs, with only their silhouette visible. The next shot shows a different person sitting, their back turned to the camera; the narrator continues: “but let’s pretend he is La Gallega”. In this pretending, this act of make-believe, lies the power of the film.

While filming her debut feature Silence is a Falling Body (2017), in which she explored the private video archive left behind by her deceased father, discovering his political activism and his life as a closeted gay man in ‘70s and ‘80s Argentina, Agustina Comedi met her father’s secret lover. A part of the Kalas group, La Delpi opened the doors of their own personal archive to the director. In Playback, Comedi invites La Delpi to recount the stories behind their VHS tapes from the late ‘80s, which capture clandestine drag shows performed just a few years after the end of the dictatorship, at the advent of the AIDS crisis. What starts as an act of archival description, a way to narrate and infuse meaning into what is on screen, quickly turns into something else. La Delpi remembers that to deal with the death of La Gallega at 25 years old, they started, along with La Colo, inventing happy endings for their friend, and telling these stories among themselves. Comedi witnesses the creative power of this act and decides to create new footage resembling the archival footage in the VHS tapes, recording it on video, and interspersing it with the old footage. In the new footage, the bar, the outfits and the hairdos from the ‘80s are recreated and, suddenly, imagination becomes reality through the devices of cinema. The remake creates a new archive.

In her article ’10 Theses on the Archive’Anand, S. (2016). ’10 Thesis on the Archive’. In O. Çelikaslan, A. Şen & P. Tan (Eds.), Autonomous Archiving. dpr-Barcelona, 79-94., Shaina Anand problematizes the archive and proposes different ways to think about it. For her, creative archives exist in a dialectical relation to traditional, ordered, archives modeled after national archives: where the latter emphasize consolidation, memory, and conservation, the former emphasize diffusion, imagination, and creation. Siegfried ZielinskiZielinski, S. (2015). ‘AnArcheology for AnArchives: Why Do We Need—Especially for the Arts—A Complementary Concept to the Archive?’. Journal of Contemporary Archaeology, 2(1), 116-125. characterizes such phenomena as ‘anarchives’, which are constantly challenging the archive. I propose to understand Playback as an anarchive.

Playback exists as a provocation to the traditional archive. There are various movements at play within it. First, the protagonists themselves do not tell a single story of what happened, but create new realities, parallel threads in which their friend could still be alive. Instead of worrying about consolidation—the telling and retelling of a narrative until it acquires a status of truth—they focus on diffusion, understood as the expansion of multiple realities. This diffusion occurs, importantly, long before Comedi ever arrives with her recording devices. She recognizes the value of this movement and adds her own: to make the intimate public through the action of remaking.

The videotapes that are kept by La Delpi were recorded at a time when drag shows needed to be clandestine for the safety of the performers, and they were kept as private records at their home, not as a part of an official archive. The various artifacts that appear in the images from these videos, including tracking errors or loss of information in the image (due to the magnetic tape being worn from use), immediately distinguish the tapes where they are stored from other tapes that may be kept and preserved in bigger, professional archives where such errors may be mitigated or corrected. The errors become more common the more a tape is played, thus becoming a sign of a repeated act of remembrance, a persistence through memory of a group of people who are now gone. When crafting her remake, Comedi not only uses a similar recording device to the one used for the original videos, but she also manages to insert these errors into the new footage, creating a seamless transition between the old and the new. The new footage acquires a status of truth thanks to its imitation of the old, and the imagined lives of La Gallega suddenly become real before our eyes.

By choosing to remake a videotape, a format often associated with the domestic and the familial, Comedi also highlights the ordinary as a site of resistance and of creation of history/-ies, away from macro-narratives which often favor violence by focusing on those moments that, as Anand puts it, “destroy the realm of the ordinary and the everyday”. By focusing on the seemingly simple moment in which La Gallega stages a performance for their friends, with no makeup and no wigs, the emphasis shifts from the politics of trauma that favours the discourse on the pain lived during the AIDS crisis, to a politics of affection. For Zielinski, an anarchive is indebted to the economy of friendship: its main affordance is to nurture the networks of affects around it; other functions are secondary.

The home videos, too, are liberated from their association with the concept of family, which favors normative conceptions of time and transmission, favoring longevity and stasis. The format is used here in a domestic setting that underscores other types of kinship, which may be temporary, intense, and chaotic: La Delpi narrates, without an inch of resentment, how, shortly after the height of the AIDS crisis, most of the survivors lost contact with each other: “each one managed on their own, as best as we could”. Social configurations that are horizontal, supportive, ephemeral, and containing multiple meanings coexist with more traditional familial ties and are rendered as valid through their careful depiction. Cinema here fulfills the promise laid out by José Esteban MuñozMuñoz, J. E. (2019). ‘Cruising Utopia’. In Cruising Utopia, 10th Anniversary Edition. New York University Press: “often we can glimpse the worlds proposed and promised by queerness in the realm of the aesthetic. Queer aesthetic frequently contains blueprints and schemata of a forward-dawning futurity”. These queer futures, similar to what Zielinski would call a utopian space of possibility, are nevertheless already there, and they have been found and made real through film.

Making the intimate public through remaking also means, in the case of Playback, to insert it into the economies of prestige of the film festival circuit. Playback had its world premiere in 2019 at the Mar del Plata International Film Festival, where it received the prize for Best Short Film, before embarking on a tour with over 60 stops at festivals worldwide—most notably the Berlinale, where it won the Teddy Award. This heightened visibility works towards the inclusion of the film into film historiography, and shifts attention to private, domestic archives that may have been otherwise overlooked by people not directly involved with them, including media archivists.

This is remaking in the margins of film history, both considering the materiality of the original pieces (video) and its scale (private). Here, it is important to note that an anarchive focusing on imagination and creation does not mean that it forgoes memory and conservation, which traditional archives are fixated on. Comedi needs the Kalas videotapes to exist to make her film but is not concentrated only on them. She needs them to be preserved, but not for the sake of preservation, but for the emotions they may activate during the creative process and beyond. Archiving needs to continue to exist for anarchives to provoke and challenge it. They are both indebted to an archival impulse but differ in the ways they relate to it: an inward movement in the case of archives, an outward one in the case of anarchives. Diffusion, expansion, multiplication—screening, screening, screening—are strategies against loss.

In Playback, the archive is displayed side to side with its remake. When we watch Playback we are not comparing it to anything we have seen before—we are being confronted with the archive and the anarchive simultaneously. The past is inextricably linked to its futures, and to a first-hand oral account guiding us through it, taking control and creating their own history. The voice of La Delpi carries the weight of the voices that came before them. This is brought to the fore every time when, during the film and in a very subtle way, the editing syncs the words pronounced by La Delpi with words pronounced by the people in the videotapes, as if they, in the past, were performing a playback to the narration done in the present. This inserts a final movement: time travel. By connecting the people that are no longer here with La Delpi’s voice through a simple editing trick, Playback manages to playfully bring them back to life.

“With each playback, we stole the divas a little bit of the eternity the world denied us,” says La Delpi at the beginning of the film. By using the remake to underscore the affection and dignity of the people who generated this archive, as well as shifting the focus away from narratives of pain and suffering that have become the norm in official queer histories of the AIDS crisis, Playback manages to give a little bit of eternity back to every one of them.