One literary text can resonate with successive generations of artists. Charting its historical trajectory, however, yields its own problematic set of pleasures, particularly when one encounters a work which remains nominally unfinished. The 1936 featurette Partie de Campagne (A Day in the Country) has been praised for the purported clarity of its director’s artistic vision, even though that director, Jean Renoir, famously abandoned the troubled production before completion. When Argentine auteur Mariano Llinás adapted Guy de Maupassant’s 1881 tale Une partie de campagne for the fifth episode of his magnum opus La flor (2018), the segment initially felt like little more than a knowing wink to Eurocentric cinephiles. Yet when taken together, a metatextual dialectic is revealed, one that raises complex questions concerning authorship, influence, and the fluid ubiquity of history.

The pastoral evocation of late 19th century France in A Day in the Country has drawn considerable critical attention to the milieu of the Impressionists, among whom could be counted Jean’s renowned father, Pierre-Auguste. That comparison gains more credence when one considers that Jean shot the film largely on location along the Seine, south of the Fontainebleau Forest. Indeed, the tributary where Renoir and his crew placed their tale of a chance encounter between two urban women (Sylvia Bataille and Jane Marken) and two rural paramours (Georges D’Arnoux and Jacques B. Brunius) was a popular site for the Impressionists to paint their work en plein air. The film’s enchantment lies in its mythic exhumation of a world Jean gleaned from stories passed down by his father. Only when we spot chimneys from factories towering above the arboreal horizon, do we sense vestigial traces of the world which would ultimately render Pierre-Auguste’s and Maupassant’s unrecognizable to modern eyes.

Whether Jean consciously intended to pay tribute to his father’s generation of iconoclasts is a question largely predicated on an auteurist reading of A Day in the Country. Such a reading remains limited, in no small part because, following a month-long delay caused by inclement weather, Jean had departed the project to shoot another literary adaptation, this time of Maxim Gorky’s The Lower Depths (Les bas-fonds). Jacques Becker, long before he made his own mark as a director, was promoted from assistant to lead director on A Day in the Country, ultimately responsible for approximately 23 shots in the final film. Even still, Becker was unable to finish shooting the script, leaving Jean’s partner Marguerite to edit the material alongside intertitles intended to fill in the narrative gaps after the Second World War, nearly ten years after the film’s initial production.For an expanded overview of the production history of A Day in the Country, see Christopher Faulkner’s insightful interview for the Criterion edition of the film.

The potential for discursive readings of A Day in the Country lies in pairing it with its symbolic remake in La flor. Llinás periodically appears onscreen to introduce several of the six episodes, four without endings, one with no beginning, and one completely self-contained narrative, comprising his 14-hour behemoth. The decision to make that latter episode a remake of a famously unfinished classic in world cinema, set within the present-day Argentine panhandle, is itself a wry punchline in a film full of sneaky humor. Yet Llinás’ polysemous ruminations on storytelling from his and our cultural past, a cosmopolitan cocktail of visual media and popular art in the 20th century, is never frivolous. What begins as a game of “spot-the-reference” for cinephiles gradually dispenses with pastiche and transforms into something more formally audacious than one may assume at first blush.

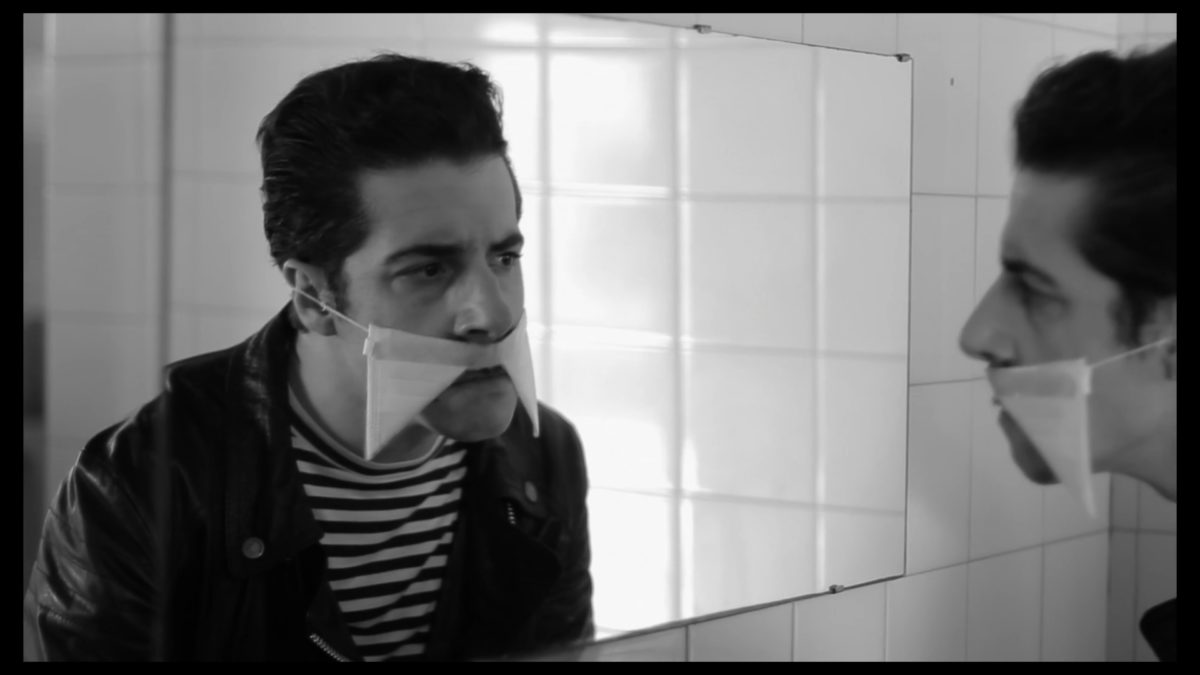

The visual references arrive both quickly and early as we follow a pair of gauchos (Esteban Lamothe and Santiago Gobernori) who woo another mother and daughter (Gaby Ferrero and Milva Leonardi, respectively). The citations of A Day in the Country explicitly underline the connective lineage between the films, particularly between Lamothe and Brunius’ meticulous mustache grooming as well as a famous shot where the men espy the women through a window of a dining establishment. La flor also retains the ancillary characters of two men in Maupassant’s tale: a divorcée (Matias Feldman) and a young man (Ramón Marquestó) whose connections to the plot proves even more tenuous here than in the original film. Both adaptations end with a parting between lovers, yet where A Day in the Country is suffused with aching melancholy, its successor opts for a more winsomely enigmatic denouement.

Yet no deviations from A Day in the Country are more apparent in La flor than in the near-total absence of sound. This aesthetic wrinkle would have doubtless rankled Renoir, whose transition into sound was commensurate with his artistic development as a filmmaker. Speaking with Maximilien Luc Proctor, Llinás explained:

…when I look at silent pictures—which I prefer to watch without any sound…—I find there’s something that we have lost in the exercise of watching pictures, something touching, something poetic and very different from anything else… So I tried that. And perhaps my suspicion was that A Day in the Country… would work better as a silent picture.Mariano Llinás and Maximilien Luc Proctor. ‘“Books on the Internet” – An Interview with Mariano Llinás’ https://ultradogme.com/2019/04/15/mariano-llinas/

In his emphasis on the pictorial over the aural, Llinás’ remarks could be read as a retrograde conception of cinema. His admission that he’s hardly seen many contemporary films would give credence to a nostalgic, even reactionary reading of La flor. But the generosity of the film lies in its expansively playful exploration of narratives that are rooted in wildly varying historical or mythic dimensions, ultimately guided by an ethos of collaboration. Like Renoir before him, Llinás has dedicated most of his career to working with a close-knit team of fellow artists through the independent production company El Pampero Cine. Indeed, the creative genesis of La flor was sparked by Llinás’ desire to work with the four actresses Elisa Carricajo, Valeria Correa, Pilar Gamboa and Laura Paredes, comprising the experimental theater troupe Piel de Lava. Paredes, who became Llinás’ partner by the end of the film’s decade-long production, would collaborate again with El Pampero Cine alongside writer-director Laura Citarella on two features: Ostende (2011) and Trenque Lauquen (2022).

The influence of these actresses on La flor only makes their absence in the fifth episode more deeply felt. For that matter, it’s significant to note that Llinás makes his final on-screen appearance shortly after he introduces the last two episodes, visibly older and grayer than when we first saw him all those hours ago. The diminishment of the primary authors of the film sends us deeper into hauntological terrain, denying the audience easy psychological identification with the players in the fifth episode. Without any knowledge of the pre-existing text, the episode keeps the audience at arm’s length, urging us to bask in the monochromatic imagery without fully comprehending the figures contained within.

A reference point for Llinás’ visual aesthetic and psychological distanciation between characters and audience can be traced back not to Renoir but to Edouard Manet. An explicit influence on La flor, Manet’s paintings sought to deny the audience what Michael Fried called “absorptive closure”, or “the walling out or curtaining off of the beholder standing before the picture”.Fried, Michael. Manet’s Modernism: or The Face of Painting in the 1860s. Pub. The University of Chicago Press. 1996. p. 262 His 1863 masterwork Luncheon on the Grass (Le Déjeuner sur l’herbe) provided the name for the 1959 film directed by Jean Renoir, yet it is with Llinás that the painting finds its closest visual kinship. Like the two couples in La flor, the quartet in Manet’s controversial canvas beckons the viewer against a sensual vista whilst, as Fried notes, lacking “psychological interiority of any kind.”Fried, p. 282

With this in mind, it can be argued that the actors in this episode of La flor operate primarily as components of a Borgesian reworking of A Day in the Country. Jorge Luis Borges’ 1939 short story ‘Pierre Menard, Author of the Quixote’ anticipated Roland Barthes’ own postulation of the death of the author as part of a quixotic enterprise in distilling the quintessence of a narrative. The question posed by Borges and challenged by Barthes was how authorial attribution can be shaped by specific historical and cultural circumstances. The major question facing us now, in an era where narrative has been converted into endlessly streamable content, is how to ascribe value to any form of media whose purported authors repurpose past iconography to commodified ends?

“I deeply believe in this concept of a framework to embellish,” Jean Renoir once remarked. “But it leads to the question of plagiarism… In art, what is unimportant is inventing the story. The story doesn’t matter. What matters is how it’s told.”Renoir, in an introduction to an airing of the film on French television. Found on the Criterion edition. His endorsement ignores the myriad problems, either ethical or political, which arise from co-opting the work of another. Yet in the context of his own upbringing during the twilight of the Impressionist Movement, the sentiment bears a kernel of truth. Manet’s work inspired Monet and Renoir the elder. While he insisted on distancing himself from the aims of the Impressionists, Manet would ultimately incorporate their flourishes in the dotted paint strokes of The Banks of the Seine at Argenteuil (Bords de Seine à Argenteuil, 1874). Furthermore, Manet’s Luncheon on the Grass also drew upon artistic sources as varied as Raphael, Antoine Watteau, and Japanese woodblocks. By subsuming the artistic trademarks of his contemporaries and successors, Manet’s work fortifies a dialectic process of artmaking which rejects a stringent binary between originality and homage.

La flor expands that dialectic by transcending aesthetic mimicry to tap into a deeper vein of Manet’s artistic spirit. Where Manet deployed such tactics in response to contemporary standards of artistic taste, the effect in La flor is one that paradoxically forgoes historical specificity while seemingly responding to its own postmodern milieu. Both a horse-drawn cart and dancers at an outdoor celebration seem culled from an inchoately sketched past.

This matrix of artistic depiction and neorealist observation culminates in the episode’s climactic sequence of airplanes in a balletic flight as sound finally emerges, specifically from the closing passages of its 1936 cinematic progenitor. In his extensive discussion of the sequence with Proctor, Llinás’ following remarks strike me as the most poignant summation of the project:

How can I be the author of those images? Or, at least, more than the pilots? How can I be author of that [when I] was there beside the camera[woman], just shooting some planes going by and making all those loops and reels. And those pilots didn’t know that we were shooting them. And they still don’t know that there’s a picture called La flor which they are in, and they will never know.M.L. and M.L.P.

The relationship between a knowing camera and an unknowing subject lies at the heart of cinema’s primordial moments immortalized by the Lumières when they sought to record everyday life. By traversing a historical path from celluloid to digital matter, this diptych of incomplete works revives the incipient spirit of discovery in filmmaking without providing a clear answer on what the future of the medium holds. These films leave us to imagine (or perhaps reimagine) a mode of visual storytelling which privileges a responsive and constant reshaping of the present moment rather than a hollow simulacrum of it. By giving us room to dream, Renoir, Llinás, and their invaluable collaborators remind us of an artistic ideal: to gift one another new ways of seeing the world we share.