In the spirit of synchronicity and ‘objective chance’ that I tried to channel in my blog on The Counselor (as intersecting in funny ways with the Coens’ Inside Llewyn Davis) and that Ruben Demasure took up in his blog on Napoléon to trace the serendipitous path that led from Gance’s film to Gravity and Computer Chess and then, during a cinephile weekend in London, to a Jacques Henri Lartigue exhibition, I stumbled upon the following introductory passages in ‘new historicist’ Stephen Greenblatt’s wonderful recent book, The Swerve: How the World Became Modern:

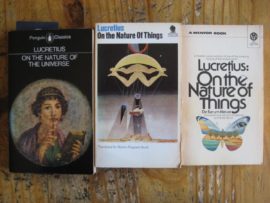

When I was a student, I used to go at the end of the school year to the Yale Co-op to see what I could find to read over the summer. I had very little pocket money, but the bookstore would routinely sell its unwanted titles for ridiculously small sums. They would be jumbled together in bins through which I would rummage, with nothing much in mind, waiting for something to catch my eye. On one of my forays, I was struck by an extremely odd paperback cover, a detail from a painting by the surrealist Max Ernst. Under a crescent moon, high above the earth, two pairs of legs – the bodies were missing – were engaged in what appeared to be an act of celestial coition. The book – a prose translation of Lucretius’ two-thousand-year-old poem On the Nature of Things (De rerumnatura) – was marked down to ten cents, and I bought it, I confess, as much for the cover as for the classical account of the material universe.

This find in the manner of Breton triggers a history of On the Nature of Things that is mainly a history of the book’s disappearance and reappearance. Greenblatt introduces as his protagonist the scholar-detective-bookworm Poggio Bracciolini, a Florentine/Roman scholar and renowned humanist, who served as apostolic secretary under seven popes (including the notorious Antipope John XXIII who was the first Bishop of Rome to be stripped of his title) and who is celebrated for having rescued a great number of classical Latin texts hidden away in monastic libraries. Greenblatt’s book narrates the ‘swerve’ that was caused by Lucretius’ rediscovery in a time of religious dogmatism, its Epicurean views on the non-metaphysical atomic materiality of the world invading the scholastic tradition and engendering a spirit of enlightenment. As Greenblatt puts it, the rediscovery of Lucretius led to the world becoming modern. It is Greenblatt’s central idea of reoccurrence that interest me here (although the link between the highly anecdotal new historicist practice and surrealist research strategies so thrillingly put to work for film studies by both Robert B. Ray and Christian Keathley, could certainly provide occasion for a future Photogénie blog). Lucretius’ work, written two thousand years ago, already contained, Greenblatt wagers, the ‘foundations on which modern life has been constructed’: the idea that everything is made of invisible particles that are constantly in motion in an infinite void, colliding in a ceaseless chain to produce matter, leading to the insight that there is no intelligent design and man is not unique, let alone the center of the universe, that there is no afterlife and that all religion is delusion. Such atheism could be (and was) perceived as deeply nihilistic, but according to Lucretius finding out that it is not all about us is actually good news: it frees human beings to live happy lives not based on superstition and commandments but on knowing. Nor does Lucretius’ materialism necessarily do away with our sense of wonder and awe. Sounding much like Aristotle who said that at the origin of philosophy there is wonder, Lucretius is certain that knowing the way things are is what raises the deepest amazement. This insight was silenced for over a thousand years and then reappeared through sheer accident. If Bracciolini hadn’t found On the Nature of Things in a remote German monastery, and if the book hadn’t been found by a scholar with deep humanist principles and an unshakeable faith in classical thought who wasn’t afraid to let an antique text change his entire world view, the swerve might have never occurred and the world, per Greenblatt, might have never become modern.

Greenblatt’s book got me thinking about Terrence Malick, initially because the cosmology in The Tree of Life, that film’s most controversial part, seems to me more Lucretian than ecclesiastic, up to and including the Darwinist evolutionary principles (or did the dinosaur indeed show pity toward his fallen prey?) that Greenblatt sees as following logically from De rerum natura. Despite being illustrative of God’s muscle-rolling in The Book of Job, the Old Testament text from which the movie takes both its motto (God speaking to Job when the latter protests his ordeal: “Where were you when I laid the foundations of the Earth…When the morning stars sang together?”) and its narrative situation, in Malick’s minutely drawn nebulae, gasses and bubbles it’s Lucretius’ – or, if you will, Einstein’s –vision of a world permanently in motion that we see realized, a universe ‘made more beautiful by its transience, its erotic energy, and its ceaseless change.’ Malick’s penchant for the jump cut, ‘le plan de coupe’ as the French call it, always an important part of his style, has become more prominent in his recent films and expresses a similar fleetingness and contingency. Interpreted philosophically, the centrality of the jump cut has reactivated the Heideggerian associations that have pursued Malick ever since it became public knowledge that he once translated Heidegger’s Vom Wesen des Grundes (ever the trooper, Ben Affleck told reporters that he re-read – ahum – Heidegger in preparation for To the Wonder but, to his frustration, couldn’t find anything relevant for his characterization). Didn’t Heidegger write that time itself is an ecstatic blending of present, future and past, and that the moment in which time is redeemed cannot be inhabited, is literally an Augenblick, a ‘moment of vision’? The film theoretician Leo Charney devoted an entire book, called Empty Moments, to this idea, that you can never be ‘in’ a moment of vision that always ‘leaps away.’ He finds it emblematic both of cinema and modernity. But let’s forget about being and time for a while, and simply restore to the jump cut, and to Malick’s style in general, its lyricism, its Lucretian subtle rhythms, and let this unique blend between poetry and philosophy come to the fore. Greenblatt reminds us time and again that Lucretius’ philosophical meditations took the form of a poem, 7400 lines to be precise, written in Virgilian hexameters, a poem containing moments of intense lyrical beauty.

There is, of course, a tradition of the poet-philosopher that extends well beyond antiquity and includes figureheads like Nietzsche, for whom antiquity, coincidentally, is an important frame of reference. Such relation between philosophy and literature, a poetic philosopher like Stanley Cavell argues, was envisioned in Romanticism, both in England (in Coleridge and Wordsworth), and, ‘more fervently and permanently, in Germany.’ German philosophy, especially Hegel and his aftermath, Cavell points out, was strongly affected by poets like Schlegel, Novalis and Hölderlin, figures that also affected the course of, or at least a specific strand of (including Cavell’s own work) American philosophy through the work of Ralph Waldo Emerson. It has become a canonical point of Malick studies that the director of The Thin Red Line was influenced by the philosophical poetry or poetic philosophy of Emerson (with whom he shares an interest in the Bhagavad Gita, the prime reference for that film’s battlefield-set dialogue), whom he probably came in contact with while studying at Harvard with the Concord sage’s greatest contemporary exegete, Stanley Cavell. The Emersonian aspects of Malick’s cinema are legion: from the recurring questioning of the monistic nature of the world and the idea that nature and spirituality are organically, inextricably intertwined (the great apparition of Emerson’s ‘Over-Soul’ that encompasses all the ‘shining parts’ clearly informing Malick’s celebration of ‘all things shining’), to the streams of consciousness, the unanswered questions that don’t seem to belong to an individual character but seem to provide an expression of Emerson’s ‘unembodied’ voices best captured in the most famous lines from his most famous poem-text, Nature(1836): “Standing on the bare ground – my head bathed by the blithe air and uplifted into infinite space – all mean egotism vanishes. I become a transparent eyeball; I am nothing; I see all; the currents of the Universal Being circulate through me; I am part or parcel of God.”

You can construct a complex family tree for all the English and German influences that conspire to construct this passage and, through it, inspire Malick’s cinema, but I will stick to my interest in recurrence, in this case that of Romanticism, a movement, or better, an aesthetic that seems to have gone out of fashion with Realism and Modernism, precisely those determinants that Vanity Celis rails against in her blog. As many literary scholars have argued, and Vanity has found, Romanticism, oddly enough, has enjoyed something of a comeback within postmodernism, if only in its obsession with the sublime as a category of both language and power (indeed, many philosophers of postmodernism, in their best moments, sound like lyrical poets!). What Malick’s cinema, in clear opposition to those clearly un-Romantic traits of postmodernism, skepticism and cynicism, certainly shares with Romanticism is, as Cavell writes about Emerson, its promise of honesty. And of course honesty, in combination with flights of lyricism, is hard to take seriously as philosophy. This is what lies at the heart of the critical disdain for Malick’s recent films, To the Wonder most of all: it cannot abide this cinema’s willed naïveté, a naïveté that almost always is coupled with the equally derogatory qualifier romantic (for a discussion of the equally disdained naïve qualities of the Sentimentalist tradition see Anke Brouwers’ blog on The Bling Ring). Malick’s naïveté is either taken at face value or, by those looking to distance the director from his work, attributed to his characters through whose mind’s eye view the narrative is constructed, even more so now that Malick is starting to do away with classical dramaturgy and dialogue. The argument for the fundamental naivety of Malick’s characters applies to the simple folk of Badlands and Days of Heaven, to some of the enlisted men in The Thin Red Line and The New World, to children, or to nature’s children in the case of the latter film, but it has no place in any discussion of To the Wonder, a film that, like the contemporary episodes in The Tree of Life, deals with relatively sophisticated characters. For better or worse, naivety is a quintessentially American quality, as Tony Tanner has proposed in his classic study, The Reign of Wonder: Naivety and Reality in American Literature, in which he charts the open, unguarded, wondering approach to life in writers as diverse as the Transcendentalists, Twain and Henry James. Tanner locates this ‘naïve vision’ precisely in the Romanticist influence on American literature, and it is indeed in Romanticism that the key treatise on naivety as an aesthetic principle is to be found.

Friedrich Schiller’s On Naïve and Sentimental Poetry (1800) starts by evoking the ‘simple pleasure of enjoying nature, an enjoyment that does not come about through any pleasure to the senses or because it satisfies any understanding or taste, but merely because it is nature.’ In this sense, Schiller argues, the pleasure is not of an aesthetic but of a moral kind. If art, in this case, poetry is to duplicate this pleasure or enjoyment, there are two preconditions: ‘First, it is entirely necessary, that the object which infuses us with the same, be nature or certainly be held by us therefore; second, that it (in the broadest meaning of the word) be naïve, i.e., that nature stand in contrast with art and shame her.’ For art to affect us as nature does it should not be stylized, but should be rendered with childlike simplicity. What we love in nature, Schiller goes on in a Platonist mode, is not the beauty of forms in itself, but the idea represented through them. What we love in natural forms is ‘the quietly working life, the calm effects from out itself, existence under its own laws, the inner necessity, the eternal unity with itself.’ As in Emerson, nature is expressive of unity, a unity we can become a part of by becoming like the transparent eyeball or, indeed, like a child. These natural forms, Schiller suggests, are what we were; they are what we ought to become once more. ‘We were nature as they, and our culture should lead us back to nature, upon the path of reason and freedom. They are therefore at the same time a representation of our lost childhood, which remains eternally most dear to us; hence, they fill us with a certain melancholy. At the same time, they are representations of our highest perfection in the ideal, hence, they transpose us into a sublime emotion.’ The Lapsarian aspects of Schiller’s treatise can lead us back to Malick via other American sources, like the highly Miltonian Melville for example, while the idea of nature as our lost childhood is expressed both through the Melanesian prologue of The Thin Red Line, Malick’s interest in children and child-like protagonists in general, and the characterization of his female protagonists, Olga Kurylinko in To the Wonder even more so than Jessica Chastain in The Tree of Life or Q’orianka Kilcher in The New World, as faun or sprite-like creatures who, in their naïve openness, are close to both nature and children. A piece of music that Malick uses both in The Tree of Life and To the Wonder is Harold en Italie, Hector Berlioz’s second symphony composed two years before Emerson wrote Nature. The choice is significant (Berlioz’s Grande Messe des Morts is also featured in The Tree of Life) for its particular link to Romanticism, Lord Byron’s epic narrative poem, Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage, written between 1812 and 1819, which in its characterization of a world-weary young man who looks for pleasure and fulfillment in foreign lands, looks ahead to the figure played by Ben Affleck in To the Wonder. It also clarifies and qualifies the naïve, child-like look that Malick would like us to adapt with his characters: the Medieval term ‘Childe’ denotes someone who is not necessarily ‘innocent’ but who has yet to attain knighthood – the title of Malick’s next film is Knight of Cups, another narrative that is presented as a pilgrimage.For many, the catch-and-grab style of Malick’s recent films has started to grate: this filmmakers’ images – shot in natural light and with an eye towards ‘moments out of time’ by the great Mexican cameraman Emmanuel Lubezki – will always be considered ‘beautiful’ or ‘poetic’ no matter what he does, but at the same time the barrage of jump cuts is taken as further proof that the director is in decline, unable to adapt his style to contemporary paradigms. Cinema Scope editor Mark Peranson complained about The Tree of Life that it’s the first of Malick’s films that wasn’t made by a perfectionist. Here he sounds like Paganini, cited in The Tree of Life, who departed the production of Harold en Italie after umpteen versions still couldn’t satisfy him (‘it could be better’). Often compared to Kubrick, Malick’s perfectionism involves time and care, but his style of shooting, since Days of Heaven, is quite different, location-dependent, much more reliant on improvisation and generally working without a finished script or much prep. This essayistic approach, central to the recent films and detrimental to classical narrative structure, can be seen as another part of his embrace of naivety, as an attempt to find a cinematographic correlate to Schiller’s simplicity. Emerson was in perfect agreement with Schiller when he wrote – in an essay on Shakespeare no less! –that the poet ‘will feel that there is no necessity to trick out or to elevate nature: and, the more industriously he applies this principle, the deeper will be his faith that no words, which his fancy or imagination can suggest, will be to be compared with those which are the emanations of reality and truth.’ Emerson’s conviction of the superiority of nature over art, to be sure, produced a disjunctive, at times unreadable style, which the poet – in a metaphor that again resonates with Malick’s aesthetic program – describes as ‘flowing.’ Emerson’s pithy compression of thought à la Montaigne is another part of his fragmentary style that can be connected to Malick’s use of paratactic editing principles (on this aspect of Malick’s style see Adrian Martin’s essay for the Criterion edition of Days of Heaven you can find here), like the attempt to reconcile a highly symbolical, mystical language with a love of colloquialisms and the language of plain folk, expressive of the idea that ‘words are signs of natural facts.’ Critics have frowned at the Jacob Riis-like vignettes of the poor and unfortunate that feel much more out of place in the upfront mysticism of The Tree of Life and To the Wonder than in the earlier Americana films, Badlands and Days of Heaven, both influenced by historical photojournalism and the ‘folk’ spirit of Edward Hopper or Andrew Wyeth paintings. Yet these people belong in a Malick film as much as Manning’s farm belongs in Nature.

Emerson’s equation of God with Nature, his rejection of theism and defense of individualism, certainly rhymes with some aspects of Lucretius’s Epicureanism, but let’s not forget that although Emerson left the ministry shortly before he wrote Nature, Lucretius was an agnostic materialist from the start. While Emerson, as a Neoplatonist, believed that there is an essence to be found behind appearances, Lucretius was a naturalist first and last, who believed that what generates wonder is understanding the material nature of things. I raise this distinction because we now need to address Malick’s religiosity, specifically the nature of the ‘wonder’ in his much-berated title (I think Knight of Cups will fare little better). That there is a theological ambition to Malick’s cinema is undeniable: in an insightful essay, Josh Timmermann explores the roots of The Tree of Life and To the Wonder in the Book of Job and the Song of Songsrespectively, also pointing to the influence of Augustine’s Confessions – a key reference point for Heidegger’s philosophy of time – and its ‘harmonization of the painfully intimate and the theologically massive and expansive.’ But calling Malick a theologist does not resolve the problem of what kind of theology it is that his films express. In any case, the theological ambition that has been prominent since his return to cinema (in Days of Heaven religion still mainly served an allegorical framework) has created discomfort with ruggedly secular critics who, as Scott Foundas has argued, have much less difficulty with the transcendental aspects of non-Christian religious films like Apichatpong’s Uncle Boonmee Who Can Recall His Past Lives. This discomfort, I want to argue, is the result of Malick’s theology being taken as doctrinal, as revealed theology, based on scripture and the belief in miracles, rather than as natural theology, where the existence of god is a purely philosophical question without recourse to any supernatural revelation. A miracle, for seventeenth-century theologists, was a ‘work of wonder,’ the true nature of which, depending on which side you stood in the Spinoza battles, pointed either to revelation or superstition. There are no miracles in Malick’s film that belong to either category. But we do get a large dose of Lucretius’ ‘wonder’ in the miracle of the Big Bang, the evolution of the species, the birth of man, the beauty of the world. The wonder in the title of Malick’s film does refer to a miracle, but one that is man-made, namely the Benedictine abbey of Mont Saint-Michel in Normandy, specifically the new monastery added to the Northern slopes of the granite island, called ‘la Merveille’ for the beauty and gravity-defying character of its architecture.

It’s puzzling how the centrality of Mont-Saint-Michel-au-péril-de-la-Mer, the ‘Mount in Peril of the sea,’ to Malick’s film has escaped notice. Neither has there been much discussion of the importance of topography, of sublime landmarks and sacred places, of the wonders of the world in general: while To the Wonder travels between Oklahoma and the Jardin de Luxembourg, and The New World moves from colonial Virginia to the Jacobean architecture of Hatfield House, The Tree of Life both repeats this move from the Midwest to a 16th century garden, the Villa Lante in Bomarzo, but, in its creational scope, also takes in geological or geo-thermical wonders like Death Valley and Hverarönd in Iceland (in this regard, an interesting comparison can be made between Malick’s recent films and those by Ron Fricke; take the description of Fricke’s latest: ‘Samsara explores the wonders of our world from the mundane to the miraculous, looking into the unfathomable reaches of man’s spirituality and the human experience. Neither a traditional documentary nor a travelogue, Samsara takes the form of a nonverbal, guided meditation’).When The Swerve was first published, Greenblatt came in for criticism by Renaissance expert John Monfasini for having painted a ‘Voltarian caricature’ of the Middle Ages as an endless period of darkness, forgetting that during the period universities were founded and cathedrals were built. Saint-Michel is an abbey that, at the time, held the status of a cathedral. The abbey is crowned by a statue of its patron saint, the Archangel Michael, who was said to have appeared to its founder. It was Michael who escorted Adam and Eve out of paradise (Variety’s Chief critic Justin Chang figures it out: ‘It wasn’t until my second viewing that I realized, in an early scene of Affleck and Kurylenko wandering about the cloister at Mont-Saint-Michel, just how explicitly the filmmaker is referencing Eden. Here, a modern-day Adam and Eve stand together in a garden of unspoiled beauty and solitude’) and, in Genesis, is seen standing at the gates of paradise, ‘to keep the way of the tree of life.’ The Archangel on the spire is the first image in a seminal account of Mont Saint-Michel, Mont Saint Michel and Chartres, written by Henry Adams in 1904, a phenomenally erudite work of history that doubles as architectural study, literary essay and philosophical treatise and, amazingly, was originally meant for private use only, as a diversion for the author’s nieces. ‘The Archangel stands for church and state,’ Adams begins, introducing the theme that will occupy him throughout the essay and that also explains his attraction to the Middle Ages: unity and ‘organicism.’ Chartres and Mont Saint-Michel inspire musings on the spirit of the age, both Adams’ own age, ‘Twentieth Century Multiplicity’ as he calls it (the subtitle of his more famous memoir, The Education of Henry Adams), and of the more harmonious Eleventh and Twelfth Centuries: ‘The whole Mount still kept the grand style; it expressed the unity of Church and State, God and Man, Peace and War, Life and Death, Good and Bad; it solved the whole problem of the universe…God reconciles all. The world is an evident, obvious, sacred harmony…One looks back on it all as a picture; a symbol of unity; an assertion of God and Man in a bolder, stronger, closer union than ever was expressed by other art.’ All this from the chapter entitled, ‘The Merveille.’ In his discussion of the kind of energy Norman art expressed, Adams refers to the only word in French which describes the Norman style, naïf, which comes from ‘natural.’ Unity and harmony, say between nature and grace, might be what the modern fractured self nostalgically longs for, but as the humanist in Adams knows, ‘science hesitates, more visibly than the Church ever did, to decide once for all whether Unity or Diversity is ultimate Law; whether order or chaos is the governing rule of the Universe, if Universe there is.’ Many a Medieval scholar was imprisoned, or worse, for suggesting that it might be tricky to prove that the ultimate Universal (God) actually exists, is really real. For Lucretius, the answer was simple: if you want gods to exist, fine, but that does not take away from the fact that the material universe was not created by any Supreme Being, but by the mixing of particular elemental particles. He was, in other words, a nominalist. For Emerson the endless variety of things still partakes of the whole and there are two unities, that of the mind and that of nature, which closely correspond. He is, in some regards at least, a realist. But, as he argues in his essay “Nominalist and Realist”, man and nature are never one thing but ‘one thing and the other thing, in the same moment.’ This is exactly what Alan Franey in the Cinema Scope roundtable on Malick found to be true of The Tree of Life: “Nature is strife, self-interest, fallen; grace is what can save man from nature and from himself. There is little doubt that this is what the film intends to display, yet don’t the images convey precisely the opposite? What I saw in this film’s glorious swirl of materiality is an extreme version of what I see around me everyday. Nature is beyond conceptual limitation and fully includes violence and grace.” For Adams, another in a long line of American Hegelians, if a Unity exists, ‘it must explain and include Duality, Diversity, Infinity.’I like to imagine Adams as the other half in Malick’s conversation with the philosophical theology of Emerson, Augustine et al, the one who most lucidly and succinctly pointed out the source for all those dualities that concern the filmmaker, ‘ambiguities’ as Melville called them, that reach back to Shakespeare’s ‘contraries,’ and, through Shakespeare, to Lucretius’ time: ‘Sex!’ he cries out with the glee of discovery. Here’s Adams’ logic:

God could not be love. God was justice, Order, Unity, Perfection; he could not be human and imperfect, nor could the Son or the Holy Ghost be other than the Father. The Mother alone was human, imperfect, and could love; she alone was Favor, Duality, Diversity…If the Trinity was in its essence Unity, the Mother alone could represent whatever was not Unity; whatever was irregular, exceptional, outlawed; and this was the whole human race.

Herein is contained the whole theology of Malick’s recent films: being human is suffering from duality, imperfection, the principle embodied by the Mother, who can love. Part of Adams paean to Medieval culture takes the form of an inquiry into the prominence of the Virgin, who for Adams is the only way out (the ‘door of escape’ he calls her) of the irresolvable conflict between Unity and Diversity (in The Education the Virgin stands for everything contemporary industrial society is not: organicism, intuition, growth, the pastoral, humanism), that leads into a genealogy of courtly love, that heady concoction of the spiritual and the erotic. If To the Wonder is, among Malick’s films, the one that most elaborately connects romantic and physical love to the idea of the Virgin as the embodiment of the first principle of Love, this is because its source material is quite peculiar. The Song of Songs is unique among the books of the Old Testament in that it seems closer to Greek pastoral poetry than to the didactic verses of the biblical canon. It is, in essence, a song, not a narrative, and no matter the attempts by theology to reclaim it as allegory for Christian love and the union of Church and the individual soul (there is that element too, of course, in To the Wonder), it is also about pleasure and desire, about ‘Sex!’ One of the terms that features in the book and was later recuperated by the scholastics and religious artists to denote the containment of Woman and the Virgin’s immaculate conception is the hortus conclusus: “Hortus conclusus soror mea, sponsa, hortus conclusus, fons signatus” (“A garden enclosed is my sister, my spouse; a garden enclosed, a fountain sealed up”). In Malick, the motif of the hortus conclusus is what explains the flights from Waco, Texas to Bomarzo, from Bartlesville, Oklahoma to the Jardin de Luxembourg, but it is generally associated, in an endless chain of similes that again reconnects the film to the Song, to the pleasures and mystical inspiration of nature, whose erotic energies, per Lucretius, engender constant change and diversification. In the Song of Songs, the garden is the site for erotic encounters, for sensual pleasures. As such, the Song was a crucial inspiration for Medieval love poetry and courtly romance. Adams shows in his extensive treatment of Medieval literature and art how sexuality and the divine met in the celebration of woman and/as nature. The style in which this meeting was rendered, was called ‘naïf,’ but as Adams well knows, this naïveté was more often than not joined with delicacy, tenderness, and art.