Allons enfants de la Patrie …

A delegation of Photogénie set out to London for the screening of Kevin Brownlow’s 5 ½ hour restoration of the 1927 silent epic Napoléon vu par Abel Gance (Napoleon as seen by Abel Gance). I look back at it as one of my cinephiliac highlights of the year. The evening before this marathon event, we also included Alfonso Cuarón’s Gravity (2013) in our programme, following J. Hoberman’s advice that “this 3-D spectacle [is] best seen on the outsized IMAX screen.” This way, together with Napoléon’s use of a three-screen Polyvision technique, we planned it to be a screen-size weekend. Yet, just as Gravity’s storyline, it turned out to be a chain of synchronicity and chance encounters by being in a certain space at a certain time; in our case, generating reverberations between panoramic vision, but also (stereoscopic) 3-D and motion in both the still and the moving image.

… Le jour de gloire est arrivé!

Film historian Kevin Brownlow premiered the most complete restoration of Napoléon to date in 2004, since then it has only been screened in Oakland, California in 2012. Because of the rare opportunity and the fact that the film’s 20 minute three-screen finale can never be translated to dvd, the projection in the Royal Festival Hall was quite a cinephile event.

Napoléon is an account of the leader’s youth and the revolution up to the opening of the Italian campaign in 1796. A fragment of the famous opening scene (the giant snowball battle) triggered the feeling of looking in the rear-view mirror to the screening of Gravity the evening before. Amidst the debris of shattering snowballs, the young Napoleon holds up a pocket mirror to look out of a trench and detect an ambush. In Gravity, in the aftermath of an attack by a cloud of space scrap, the man with the plan, Kowalski, looks into a mirror attached to the arm of his spacesuit to Stone, who is secured to him by a cable and floating behind. Two frames within a frame, in a respectively all white or black environment, and almost each other’s mirror image.

Although without elaborating, Hoberman explicitly places Gravity in a tradition that includes Abel Gance’s Napoléon, reinforcing our double bill. Kristin Thompson picks up on his remark with the bold statement that Gravity is better than Napoléon. I don’t want to get dragged into a game of calling one of the two films, each with their own context, “better” than the other. However, I will try to explain why I enjoyed Napoléon more than Gravity.

What links the two most is the fact that both films ventured into new frontiers of camera mobility. To attain fluid camera movements, Gance made use of the specially designed lightweight portable Debrie Photociné Sept camera. For Gravity, a rolling, multiply-jointed camera mount with motion-control was designed, called ‘Iris’. It was used in a newly invented closed off ‘LED light box’, in which the pre-visualized space environments are projected. The actors are placed in the Box to get the matching lighting on their faces, coming directly from the projected animation. However, seeing the freedom of the camera in Gravity and Napoléon back to back, I couldn’t avoid the feeling of missing the authenticity of the profilmic event in front of the lens. I agree how visually stunning Gravity looks and acknowledge the simple fact that you can’t actually go into space to shoot. Yet, whereas one innovative aspect of Napoléon was precisely its location shooting (on Corsica and elsewhere), the only “real” thing one is looking at in Gravity are the faces of the actors (whose bodies sat in a 12-wire harness and were put in position by puppeteers). All else is illusion. It’s the camera and the animated effects that are spinning. The faces were pasted in; even the space suits were created digitally. Inversely, Gance strapped a camera to a man’s chest, instead of scanning around a body.

There are other interesting contrasts between Gravity’s rig and light box and Napoléon’s techniques. Whereas Gravity’s swaying shots are done with a computer-controlled robot arm, Gance mounted his camera on a huge pendulum swinging back and forth. Whereas Gravity installed its camera in a big closed off LED light box in which everything was filmed, Gance put his camera in a waterproof box and physically threw it off a cliff into the Mediterranean. Although Gravity’s final scenes were filmed on 65mm (but in the box), this is something else than watching an animation of a space capsule crashing on the water. Whereas Gravity commissioned a camera mount and software from a manufacturer of robots used on car-assembly lines, Gance made travelling shots of the landscape by strapping the camera on the back of a running horse. In Gravity, the uninterrupted camera movement isn’t an actual continuous run of the camera, nor is it an unnoticed digital stitch of several takes, but rather it is the creation of special-effects animation with the real faces pasted into it. Although the paradox that space in Gravity looks hyper real and more scientifically correct than any space movie before, my experience of it was eclipsed by the excitement of Napoléon’s ingenious craftsmanship.

Not only does Gravity lack the physical aspect of Gance’s movie, but also a metaphysical dimension that can take such content to a higher level (Tarkovsky’s Solaris remains unsurpassed in this). The stripped down narrative (one person overcoming obstacles to achieve a goal) is a welcome endeavor and genuinely thrilling, but doesn’t offer much more than a story of ‘letting go’, of taking life back into your own hands, supported by a whole arc of metaphorical rebirth. (Cuarón talked about how he had to fight against the studio suggestions to drop the single location concept in favor of flashbacks, cuts to Houston where Stone would have a love interest and even a rescue mission after landing.)

The same goes for the use of sound. Notice that actually both the silent Napoléon and Gravity (given the laws of outer space) start off with a mute canvas. This offered a shocking potential, yet Cuarón argues: “I thought about keeping everything in absolute silence. And then I realized I was just going to annoy the audience. [W]hile I’m sure there would be five people that would love nothingness, I want the film to be enjoyed by the entire audience.” Maybe, I am one of those five then, but the often praised score, with its rising orchestral pieces, isn’t really a departure from the classic structure, guiding the audience’s emotions to the film’s climax, with the extreme low angle of Stone set against heaven, as its low point.

Indeed, one of the most interesting aspects of Gravity is how it shows its own compromise between unconventional experiment and the Hollywood studio demands, i.e. the even liberal Warner. Likewise, from its very conception, Abel Gance envisioned his film as being both populist and radical, uniting avant-garde experimentation with commercial appeal (Cuff, 2013: 95). It was Gance who once said in an interview: “My greatest mistake was ever to have compromised. My greatest achievement has been to survive.” (Colombo, 1979: 140). A lot has been written on Gravity as “blockbuster minimalism” and “blockbuster modernism”, as “an experimental film”, down to “the most expensive avant-garde art movie ever made” – the last two critics even drawing comparisons with Michael Snow’s structuralist film classic La Région Centrale (1971) beyond the use of a programmed mechanical camera arm. For the abovementioned reasons, these are all terms that I don’t want to associate with Gravity, notwithstanding its technological innovations.

The true avant-gardist move of the weekend, however, happened 5 hours in Napoléon, when the screen widens to include two additional panels. I was spinning. Now, three 35mm 1.33:1 images were projected side by side, making for a total aspect ratio of 4:1. This couldn’t beat the immersive IMAX experience of Gravity, shown letterboxed in its original aspect ratio of 2.35:1, on the UK’s biggest, curved cinema screen (26m by 20m with a total screen size of 540m²). However, it is not size that matters, but how Gance uses his canvas. I found Polyvision at its best when not merged into a single panoramic vision, but when exploiting the possibilities of lateral montage of symmetrical, contrasting or complementary images, even on the verge of abstraction.

Strikingly, scenes of the triptych have also been filmed in 3D and color. (Gravity makes use of non-native, post-processed, but effective 3D.) Brownlow hasn’t found this footage (yet?). Simultaneously with the three-camera rig, Gance used a second camera, filming in an early color process and in a dual-strip anaglyphic stereoscopic process. Gance viewed the dailies using red and green spectacles, but decided not to use them, judging it would be too distracting (Zone, 2007: 138; Brownlow, 1968: 559). Indeed this may have been a cacophonous layer to a triptych that is already impressive enough.

One tweet after the screening used the words of Stravinsky on Beethoven’s Große FugeIn his film score, composer and conductor Carl Davis uses Beethoven’s Eroica Symphony, which was originally inspired by Napoleon’s actions and ideals. When the piece was finished and Napoleon declared himself emperor in 1804, Beethoven changed his mind. Pieces by other Napoleon contemporaries that are used in Davis’ score are Mozart, Haydn, a tune from Napoleon’s favorite opera (Paisiello’s Nina) and La Marseillaise. to describe the experience perfectly: “This is contemporary and will be contemporary forever.” Indeed, what Napoléon does, is largely unseen in a cinematic contextGance’s Polyvision is seen as a precursor to the Cinerama process, which premiered 25 years later and has a largely similar three camera configuration. Although it triggered competition to introduce other widescreen formats, Cinerama remained a novelty before expiring in 1962 (see David Bordwell’s “The wayward charms of Cinerama”). Andy Warhol’s 3 ½ hours split screen movie, Chelsea Girls (1966), was originally projected onto one screen by two 16mm projectors simultaneously. Multi-screen films gained momentum in the mid-sixties around two world fair’s: the 1964 New York World’s Fair and Expo 67 in Montreal. For the former and most relevant here, Francis Thompson and Alexander Hammid made To Be Alive! This 18’ documentary was shown on three separate 18-foot screens. Unlike Cinerama, the three panels did not form an entity but were each separated by one foot. A tradition can be traced up to Peter Greenaway’s development of a multi-screen language, for example with the 2005 live projection on 12 screens of the 92 Tulse Luper Stories. At Expo 67, Christopher Chapman’s multi-image film technique in the 17’ A Place to Stand displayed up to 15 images in dynamically moving panes on one screen and didn’t require special equipment or a special theatre. Different from multi-screen films, it led to another direction: the popularization of split screen movies, with 1968 classics as The Boston Strangler and The Thomas Crown Affair, who use up to 5 or 6 splits. In Numéro Deux (1975), Godard invented new ways of splitting the screen by filming the initial video footage being played back on monitors. The split screen reappeared as a digital technique (easier than refilming on an optical printer using a matte screen), maybe most (in)famously in Mike Figgis’ Timecode (2002) that played as a simultaneous quad grid. But more interesting in the context of Napoléon is Duncan Roy’s AKA (2002) which is presented in a widescreen triptych. One could even go back to the 1913 film, Suspense, in which female director Lois Weber superimposed a triangle on screen, creating a triptych of simultaneous events. Most of the time, with multi- or split-screens, simultaneity is central. Gance was truly ahead of his time by fragmenting continuity, superimposing past, present, future and metaphor, but also mixing colors, close-ups and long shots., but actually prefiguring the dispositif of a (multi-channel) video installation. One could think of Waterloo Forever! (2010), a video installation by the Belgian visual artist Koen Theys using three projectors, switching between the battlefield panorama, and detailed actions on one or all of the three screens. On Tumblr, a Swedish cinephile made this visual comparison between Napoléon’s tricolor triptych finale and a work by the father of video art, Nam June Paik’s Video Flag X (1986). His series of Video Flags (X, Y and Z; 1985-86) shows fast cut images that alternate between the stars and stripes that define the American flag and images from news reports, the statue of liberty and faces of American presidents. In 1982 Paik even used the French flag as the basis for his sculptural television construction Tricolor Vidéo, composed of 380 video monitors. Both Napoléon and Paik’s video flags make use of a combination of timers and multiple analog playback devices to get the images onto the screens, respectively three interlocked 35mm projectors and a number of laserdisc players.

If Gance took the use of handheld recording a step further, Paik is a symbol of the artistic use of the new affordable consumer video cameras in the sixties. When he moved to New York in 1964, he was one of the first to work with the legendary Sony PortaPak. A film shot with the PortaPak one decade later, William Eggleston’s Stranded in Canton, was the aesthetic inspiration for a 2013 film, shot in video, which we saw the day after Napoléon at ICA London.

Computer Chess

Just as the opening of Napoléon reflected a moment in Gravity, the introduction of Andrew Bujalski’s Computer Chess (2013) threw me back to the centerpiece of the weekend. In it, the host of a one-weekend tournament of computer chess – the central event of this mockumentary – refers to the mythic game between Napoleon and The Turk, a fake chess-playing machine. Bonaparte, a passionate chess player, allegedly was defeated by this Automaton at Vienna’s Schönbrunn Palace in 1809. The day before, we had seen Napoleon defeat General Lazare Hoche in a game of chess with his future wife Joséphine de Beauharnais at stake. What was really interesting however, was how the video aesthetics of Computer Chess played off against the formal silent film techniques of Napoléon. The reportage or home video style is a radicalization of some of the handheld shots executed in Gance’s film. Bujalski’s use of split screens and the central element of the chessboards recalled Gance’s kaleidoscopic imagery, especially his checkered nine-image rendering a pillow fight in the young Napoleon’s boarding school. The film’s 4:3 video format (theatrical 1.33:1 ratio) resonated with the squares on the chessboard. The sometimes explanatory text at the top of the screen can be seen as the title card of the video days. Besides split screens, Bujalski even created an iris shot (a cheap 6mm surveillance lens was used to create a big vignette on the 2/3 inch analog camera tube). The iris represents a computer’s eye view (quoting 2001: A Space Odyssey) of two people talking in front of the machine.

Of course, the face-off between technology and the human will or the trouble to (de)connect, brings Gravity back to mind. But then there is also the scene in Computer Chess in which the members of an encounter group re-enact their own births, including the cutting of the umbilical cord. Keeping in mind the most explicit of Cuarón’s heavy rebirth metaphors, i.e. Sandra Bullock curled up in a zero G foetal position against a backdrop of tubing and a womb-like airlock door, this became all too freaky. In the end, Computer Chess is of interest for its stylistic experiment with the video medium, but I find it too quirky to be funny or meaningful. The film appears in many international lists of the best films of the year, but was completely ignored in Belgium.

Lartigue

To close off the weekend, we visited an exhibition of the French photographer Jacques Henri Lartigue at the Photographer’s Gallery, which featured pictures of his wife, Bibi, and their social circle. I was surprised to find out that just as his French compatriot and contemporary, Abel Gance, Lartigue not only experimented with 3D, but also was a pioneer of early color film. In a smaller adjoining darkened room, color glass plates were on show in back–lit light boxes. Lartigue got his hands on the first commercially released color technology by the Lumière factory in 1907. The Autochrome Lumière process uses a coating on the glass plate with a mosaic of dyed grains of potato starch.

Next, in the middle of the room stood a large box with three binoculars installed on either side through which images could be watched in stereoscopic 3D. Actually, I learned that many of Lartigue’s most famous images were originally taken in stereo. There are about 5,000 glass stereo negatives in the Lartigue archives, making up about 5% of all the photographs he took in his lifetime, but probably nearer 25% of his published photographs (interview with author Bill Hibbert, 2007). But just as Napoléon’s impractical triptych technique prevented any serious distribution and exhibition, so did the difficulty to reproduce Lartigue’s stereo photographs make it impossible to show them in 3D at the time. (Just as Napoléon could only be rediscovered in 1980 because of the work of Brownlow, Lartigue was only rediscovered with a MoMA exhibition in 1963 and by a wider audience through a first book publication edited by Richard Avedon in 1970, Diary of a Century: Jacques-Henri Lartigue.)

Interestingly, Lartigue’s camera allowed him to switch between panoramic and stereoscopic photography, two stylistic features we were exploring all weekend. In 1904 Lartigue received a Spido-Gaumont 6×13 cm glass plate stereoscopic camera, a gift from his father. By moving a horizontally sliding front, one of the two stereo lenses could be blocked off, while the other was positioned in the center. In 1912 Lartigue bought a Klapp Nettel folding camera for the same size of glass plates and with the same conversion capability. This one allowed one lens to be removed and the other to be slid sideways to the central position. Comparable to Gance’s triptych, Lartigue had to make a choice between using the overall image size of 6×13 cm or split it up (examples here).

Discovering these images by staring through these viewers again reminded me of a shot in Napoléon, which is actually emblematic for the whole of the weekend: the POV iris shot of admiral Nelson’s hand telescope, spotting the ship ‘Le Hasard’ (meaning chance, luck or fate). Nelson doesn’t get permission to “scuttle that suspicious-looking vessel” and is ordered “not to waste powder on such an insignificant target”. Nelson doesn’t know that this boat has his future adversary on board, who was just saved from a storm by “historic providence” (as the title card reads) when his two brothers sailed by with ‘Le Hasard’.

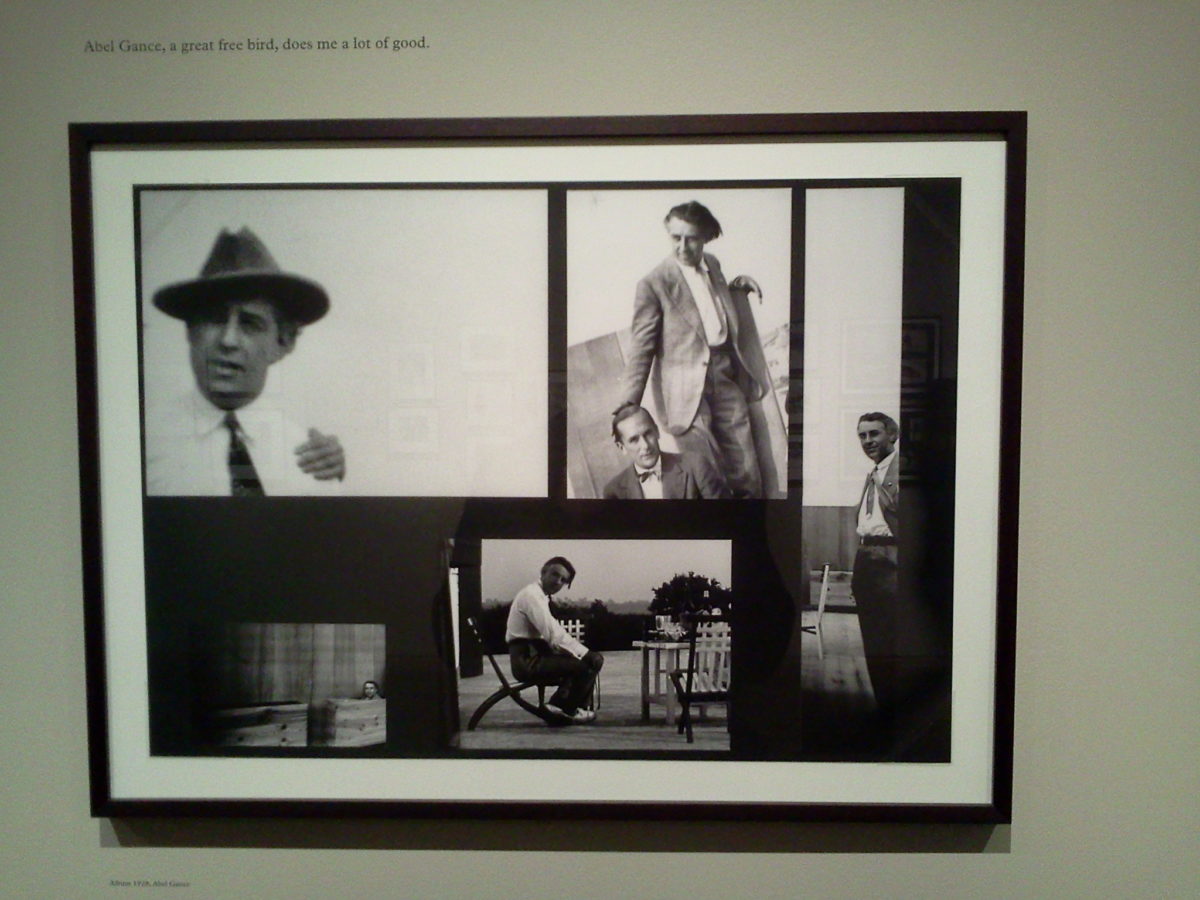

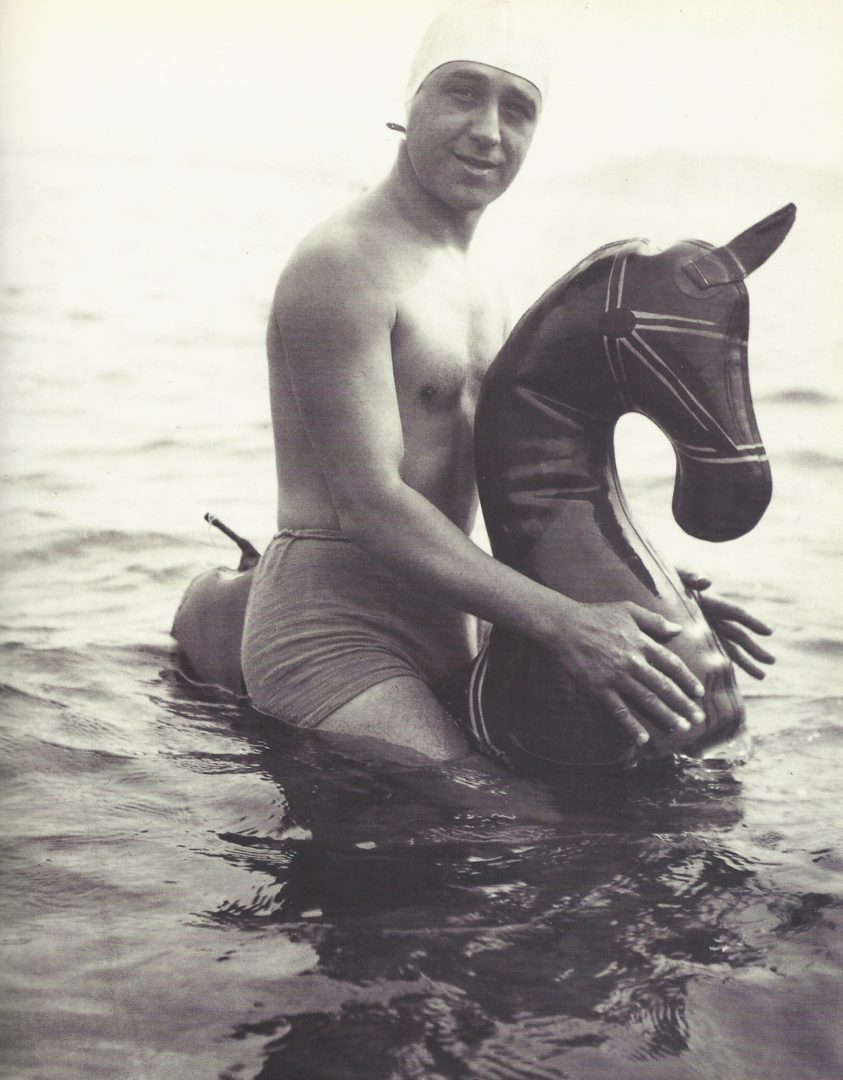

Unable for us to foresee, already on our way to the exit of the Lartigue exhibition, we stumbled upon the ultimate synchronicity of the weekend. There he was. Abel Gance in a polyptych of pictures, from a 1928 album. It turns out that Lartigue met Gance in the early twenties and was invited to work on his sets on several occasionsLartigue worked as a still photographer with Jacques Feyder, Robert Bresson, François Truffaut and Federico Fellini (Lartigue plays the role of the resigned priest in his Ginger e Fred, 1986). Lartigue also worked on the Film Festival in Cannes from 1946 until his death. Lartigue’s photographs make an appearance in several of the films of Wes Anderson, who openly acknowledges the French photographer as a source of inspiration.. Gance even offered him the job of assistant on the shooting of Napoléon, but he refused. A couple of months after the premiere of Napoléon, Lartigue took this picture of the director of grandiose horseback battle scenes.

In his diary, Lartigue – he himself very much the photographer of motion (his mid-air freeze frames of leaping, jumping and throwing, as if to defy gravity, were revolutionary at the time), mobility, speed (car and motor races) and new technologies (the first attempts to fly) – called Gance “a great free bird.”

I would like to conclude with what film maker and theoretician Jean Epstein wrote on mobility – key to his concept of photogénie – clearly with Napoléon on his mind:

“It was and still is very important to set the camera free in the extreme: to place the automatic camera in footballs launched in rockets, on the back of a galloping horse, on buoys during a storm; to crouch with it in the cellar, to take it up to the ceiling heights. It doesn’t matter that these virtuoso positions may seem excessive the first ten times; the eleventh time we understand how necessary and yet insufficient they are. Thanks to them, and even before the revelations of three-dimensional cinematography to come, we experience the new sensation of exactly what hills, trees and faces are in space.” (Epstein in Abel, 1988: 64)

If the quality of photogénie manifests itself in highly personal epiphanic moments, fleeting actions, marginal details, seemingly arbitrary images – whether still or in motion, whether through the Epsteinian belief in the camera’s ability to record physical reality or the Dellucian support of the creative input of the filmmaker (cf. Gravity) – then it has proved to be very much alive throughout this weekend of wonderment. To put it with the label that Gance used in the right bottom of all title cards that allegedly note actual incidents and quotations, it was:

(Historical)