Last year, fiercely independent filmmaker Andrew Bujalski treated filmgoers to an unforgettable experience. Computer Chess, his fourth feature, takes the viewer on a nostalgic and utterly cinematic trip back to the youthful days of computer programming, when personal use of computers was very limited and optimism about artificial intelligence prevailed. In an unspecified year (sometime before 1984), various computer programmers come together in a hotel to face off their newly developed programs against each other in a computer chess tournament. For the duration of this event, the hotel becomes a haven where programmers, Tech majors, chess aficionados and mathematicians gather to probe the limits of computer technology. The film takes us on a tour of the event, providing us with an insight into what such chess tournaments might have been like at the time. Computers are being carried around and installed all over the place in the competition room and debates are being held between members of various programming teams to discuss and philosophise over the future of computers and their potential advancements over human intelligence. Once the actual tournament starts, the chess players are turned on, the buzzing noises of the processors and monitors begin to dominate the local soundscape, and the atmosphere in the competition room is almost totally computer-driven. Given the overwhelming nerdy presence in the hotel and the undeniable tendency of these individuals to indulge in their passion, thus making them easily identifiable as geeks and nerds, the nostalgia for the optimistic cyberpunk era depicted in Computer Chess quickly turns into fetishism. Much of the casting was done in this spirit; the director and producers were actively looking for nerdy-looking people to act in the film, and preferred even to use actors, mostly non-professionals, who themselves dabble in the world of computer programming and artificial intelligence. This might not be a very enlightening or challenging observation – it’s quite obvious from the get-go that we are dealing with some seriously nerdy material – yet the notion of the computer chess event as a fetishist fantasy realm becomes interesting when one takes a closer look at what else is happening in Computer Chess and realise that it doesn’t end there. It is more than, say, merely a fictional rendering of Seth Gordon’s The King of Kong (2003). Although one could discuss its style and trace some of its influences, Computer Chessremains a very mysterious film, which could easily be misinterpreted as being quirky in order to seem interesting.

In the current cinematic landscape, the most immediately noticeable element about Computer Chess is its look. Even within the modern American independent cinema movement almost any shot in the film will confuse a person into thinking that he is looking at footage from some old TV relic taped off a long-abandoned public access channel, a bad documentary from a couple of generations back. This is the direct result of Bujalski’s very first idea in relation to this particular project: in the very beginning, before the computer chess element came into play, Bujalski had wanted to shoot a film on video: “I know that I had the fantasy of shooting on these old analogue video cameras,” he said in an interview with Craig Keller.This interview is available as a bonus on the Masters of Cinema Blu-ray/DVD edition. The fact that the first choice involved in the creation of Computer Chess was a particular kind of old video camera suggests that Bujalski was very aware of the retro look his film would end up having. Given the video aesthetic, it is difficult to ignore the comparison with Pablo Larrain’s recent Chilean history drama No (2012), and, as Peter Bradshaw suggests, Harmony Korine’s utterly confounding – yet strangely poetic – Trash Humpers (2009). All these films show an obsessive interest in the artistic potential of video footage, yet each film uses it in a completely different fashion.

In her cinephiliac blog post on Park Chan-wook’s Stoker, Vanity Celis mentions Michel Hazanavicius’ The Artist (2011) as a film that uses silent technique as a device with which to recapture the power of the image. Although it is very much to The Artist’s credit that it brought the aesthetics and charm of silent cinema back to the general public’s attention, it should also be noted that The Artist’s gimmick of being silent is quite strongly contradicted by its all-important (and multiple-award-winning) score which often draws the viewers’ attention away from the image, towards the music. In a somewhat similar throwback to a particular era and its corresponding iconic style, No uses video to create a look that matches the film’s story, which is clearly defined as an attempt by a TV-crew to direct advertising campaigns for the 1988 “No” campaign in opposition to Pinochet. No makes consistent use of the video format in its imagery and makes it less of a (failed) gimmick than the ‘silence’ of The Artist. However, since all other dramaturgical devices in the film and the acting styles of the various performers are very conventional, the retro-look of the film does stand out as being a little goofy.

Trash Humpers takes another tack. It does not use video in adherence to narrative logic or period demands, but as a fundamental artistic choice to evoke the bizarre netherworld of home video. Harmony Korine, ever so interested in unsung cultural trends of a less ‘proper’ nature, seems to evoke the atmosphere of weird home-made videos, found footage of people engaging in seriously deranged activity that defies understanding, yet deserves attention and contemplation.

Computer Chess falls into a different category, one which has a bit of both worlds. The analogue video format is not merely used as stylistic device to emphasise a story and the period in which it is set (as in No), and neither is it used to emulate a particular type of deranged home-video culture (as in Trash Humpers). In this case, it is not quite so simple to determine exactly what the video component means. However, describing its effects on the film does offer some interesting insights into the fascinating world of Computer Chess.

The old video camera Bujalski had been fantasising about turned out to be a Sony 1968 AVC-3260 B&W (a type of camera which generally sells on eBay for under $100), which was subsequently stripped of some of its parts and tweaked to fit a specially constructed rig to accommodate the analogue video format and feed the sound and image into a digital processor, making the recorded data available for digital editing. To enter into further detail concerning the equipment used to convert and process the data would be too tiresome for both reader and writer, and would probably draw attention away from what makes the film’s look so interesting and unique, as it might actually explain the numerous glitches left behind in the image. As a result of the experimental analogue cum digital camera equipment, many shots in Computer Chess experienced some kind of strange visual manipulation with regards to light and shadow, but there was also a certain amount of video interference, providing the film with an unexpected, yet suitably authentic retro look and feel. “The camera threw all kinds of curveballs at us,”This interview is available as a bonus on the Masters of Cinema Blu-ray/DVD edition. says Bujalski in defence of the complicated recording process, having fully embraced those glitches and welcomed the weirdness of their random occurrence. One of the curious visual features of Computer Chess is the video vapour trail left behind when an object moves within the frame or when the camera pans away or towards certain objects or bodies. This effect, although not anticipated by the crew, establishes a spectral presence in the world of the film and is very effective in establishing the diegesis as a strange place where strange things happen. Other unexpected visual effects in Computer Chess include sudden invasions of the image by video static: as a scene is being played out, bursts of white noise and other types of snow appear over the image.

Such flaws accentuate the intimate relation between the film’s form and its content, which are both something of a fetishist throwback to a past age of computer and video practice long since outdated. But again, there’s more to it.

After the viewer is introduced to the competition and the various participants, it would only be logical to assume that the event itself will be the main focus of the film. Since it has all the bearings and ingredients of an informative period piece, one would expect that the film actively engages in discussions about computers and artificial intelligence. This is not the case. What Bujalski seems to be doing here, is simply to plant notions and conceptions of nerdiness and artificial intelligence in our heads. He is forcing us to think about the scientific, the technological and the digital, directing our attention towards such determinable elements. Slowly but surely, however, Bujalski starts inserting other players into the Computer Chess field – both human and non-human – to mess with the mind of the viewer and to throw those off track who thought they had the film all figured out. With an impeccable sense of comical timing, Bujalski acquaints us on a more intimate level with some of the computer chess combatants and follows them as they wander around the hotel, through the hallways, in and out of bedrooms and into conversations with other residents at the hotel. These encounters are often of a quirky nature, and allow the film to deviate from what was previously thought of as the main subject, the computer chess event. In this way, the film might be interpreted as a retro variation on the Robert Altman ‘event’ model of narrative construction. Throughout his career, Altman kept turning to events as subjects for his films. In Nashville (1975), he staged large-scale musical and political events surrounding the United States Bicentennial, in Buffalo Bill and the Indians, or Sitting Bull’s History Lesson (1976) he satirised Buffalo Bill Cody’s entertainment extravaganza ‘Wild West Show’. Closer to the mark here, however, are HealtH (1981) and Prêt-à-Porter (1994), films about organised events (a health awareness convention and fashion show respectively) that take place at hotels. The combination of subject, location and Altman’s signature ensemble approach is very similar to what goes on in Computer Chess. Therefore, an interpretation that makes Bujalski’s film adhere to the Altman model makes this strange film somewhat digestible. (At this point, I must stress the fact that my comparison between Altman’s and Bujalski’s event films makes no claim as to their quality, for, as an immense Altman enthusiast, I am loath to admit that HealtH and Prêt-à-Porter are not very good at all.) But again, there’s more to it than that.

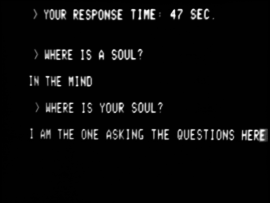

The most enigmatic – and, in my opinion, the most meaningful – of all of Computer Chess’s quirks, is most definitely the touch of the supernatural that recurs throughout the film. As the film progresses and becomes headier, the innocent-looking pillow shots of empty (or cat-infested) hallways begin to take on another meaning. Rather than being there to “suspend the diegetic flow,” as Noel Burch might have put it,In To the Distant Observer, Burch says of pillow shots that they “suspend the diegetic flow […] while they never contribute to the progress of the narrative proper, they often refer to a character or a set, presenting or re-presenting it out of a narrative context.” they resemble the haunting long takes of Chantal Akerman’s contemplative Hôtel Monterey (1972) and reveal a strange, enigmatic presence in the hotel. Although Akerman (under whose tutelage Bujalski wrote his thesis in his final years as a film student) is primarily concerned with the pictorial beauty of her shots, they are nonetheless filled with an aura of mystery. It is a similar mystery at work in Computer Chess, which quickly spreads from the hallways and permeates the entire film. An obvious supernatural element in the hotel, one that clearly pits itself against the scientific computer-world of the programmers, is the mind-body meditation workshop, taking place simultaneously with the computer chess event. As the participants in this workshop hum and meditate their way into altered states of true spiritual awareness, they exert an influence, for better or worse, on the computer guys and start messing with their worlds. However, nothing could be more terrifying to a computer programmer, than to discover that a computer actually has a mind of its own. Another instance of supernatural presence in Computer Chess – and the one that is deservedly given the most attention in terms of narrative development –occurs when one of the participants discovers that his team’s computer, Czar 3.0, prefers to face a human opponent rather than another computer. Is it more challenging that way? Is the computer merely being contrary? Is it merely a programming error? It certainly seems that this computer, in the great tradition of the HAL 9000 from Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968), has acquired a mind of its own, a will of its own and perhaps even a soul. This much is steadily revealed to us as we become acquainted with its programming team, and the HAL-like character of their computer is revealed. In his article on Abel Gance’s Napoléon, Ruben Demasure describes one of the references to Kubrick’s film: an iris shot of its two programmers meant to suggest Czar’s POV. In a later scene, the third team member is doing research on Czar and finds himself in philosophical debate with the computer, asking questions about mind, body and soul. Czar’s stern reply to the question, “Who are you?”, is the sonogram image of an unborn baby, a reference, perhaps, to the space baby in 2001: A Space Odyssey.

There are many more scenes and gags that send the film into even further directions than I have discussed. And the wonderful weirdness of Computer Chess does not even stop at the end of its running time. Fans of the film and its strangeness will be thrilled to learn that the British distribution company Eureka! Has released a crispy-looking, finger-licking good Blu-ray and DVD of Computer Chess as part of their Masters of Cinema series, featuring wonderful artwork by Cliff Spohn and, as if the film itself wasn’t bizarre enough, a commentary track recorded by an enthusiastic stoner. In the end, it seems not to be possible to write about Computer Chess with a fair degree of accuracy, nor is it feasible to provide a review that will do the film justice. For all the pleasantly surprised critics and the positive responses they provided, Computer Chess remains an elusive piece of work which, as in its narrative, has a ghost at the heart of the machine that makes it impossible to pin the film down, to say exactly what the film is.