Politics sneaks into the story whenever there is something important to talk about, as we can see in the news reports on the current pandemic—a respiratory virus that theoretically affects every human in the same way has radically different consequences depending on our medical care history, job security and benefits, or whether we can afford to comfortably stay home and miss a couple of paychecks. It is hard to imagine any domain of human existence—morality, receptiveness to art, outlook on far-away lands and world history—that isn’t shaped by a huge cognitive bias brought about by political reasons.

Cinema and politics have interacted in various intricate ways throughout the past hundred years, in ways that make it really hard to divide ideology from aesthetics and industry. Soviet films of the 1920s had the task of shaping consciousness in a new, post-czarist, territorially expanded nation, but they also catalyzed innovation that changed the course of film history. At the other end of this century, contemporary political films channel several centuries of political thoughts and fully benefit from a quasi-global freedom of expression, and yet they are often limited in audience reach by the festival infrastructure marketing procedures and/or digital media algorithms.

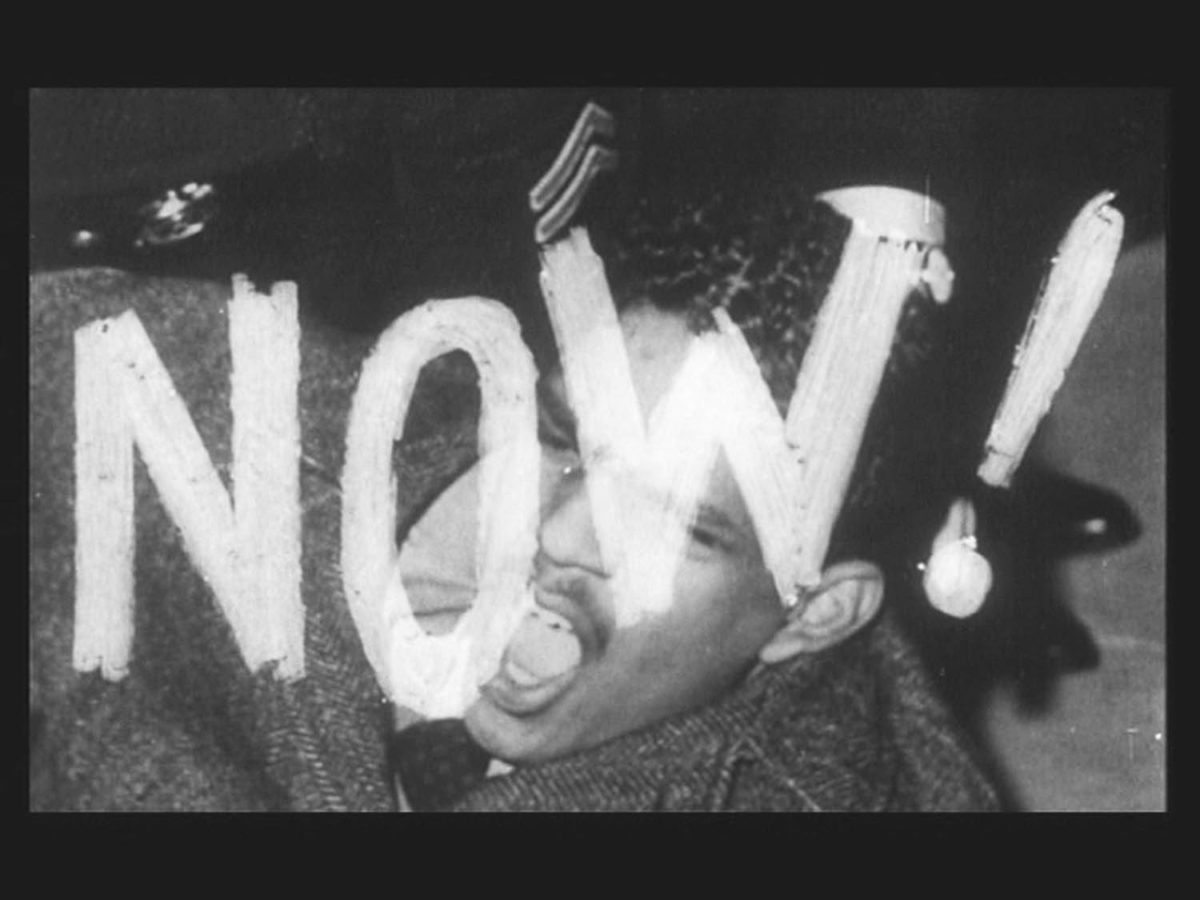

The audiovisual medium has an advantage over art forms with longer traditions, both in its ability to directly record reality and in the portability of its content—in theory, at least, the most reluctant spectators’ old-world mentality could be confronted with glimpses of the new and better social order, and the largest or least urbanized nation could be trekked by film caravans. The walls of living spaces, theaters and museums were quite easily torn down by the technologically-reproducible work of art.

The current photogénie dossier examines the political role of cinema in its various phases of interdependency with history at large. One facet of this relationship is cinema’s change of course after two drastic regime changes, one pro-capitalist (in Romania, after the fall of the USSR & the execution of Nicolae Ceaușescu) and one anti-Western (in Iran, inaugurating the rule of the Ayatollah Khomeini). Andra Petrescu examines documentaries on the Revolution made later than 1989 to identify their various functions: coming to terms with (and maybe even taking revenge on) the past; writing a plausible (though not necessarily accurate) narrative to give shape to the tumultuous events; announcing the newfound freedom of expression that is not only a license to tackle what was previously taboo, but also comes close to being a formal constraint leading to a new genre of meta-documentary. The Romanian Revolution became a landmark in television history due to its then-novel capacity to ensure live broadcast of momentous events while still falling short of making history visible. Post-Islamic Revolution Iranian cinema, on the other hand, meant the protective reinvention of a homogeneous national culture—as Hossein Eidizadeh explores in his essay, the guidelines of a domestic cinema post-1979 were gradually crystallized after more urgent matters were settled, first by opposition to the mainstream called FilmFarsi, then by encouraging pedagogical films that connected to their audiences. Although the production of authoritative regimes is often reduced to keywords like censorship and leaks, political orders and coded in-jokes between filmmakers and audiences, both essays reveal how these matters are in practice much more complicated: for instance, films with screening permissions might still not find exhibition venues; and dissident filmmakers who are eager to speak out against oppressors might still be short-sighted about certain aspects of the world they’re in.

Few cinematic movements—and even fewer state-sponsored ones—were so apparently full of paradoxes as Cuban cinema of the sixties. Fully endorsed by the Fidel Castro administration to shape Cubans’ revolutionary outlook, generously funded and distributed and with very little formal constraints, the cinema ushered in by ICAIC and filmmakers like Tomás Gutiérrez Alea seemed like a radical’s utopia—fit for the masses, intriguing for cinephiles, and not mincing words either in criticizing the bourgeoisie or pointing to the shortcomings of the Revolution itself. In spite of the unfulfilled expectations of creating a better, fairer world in the second half of the 20th century, the least Cuban cinema did for hopeful leftists is to keep the dream of oppositional cinema intensely alive.

Talking about the normativity of culture begs the question of whether the call for political action is not only possible, but mandatory, for peripheral groups. Should, for instance, queer cinema urge spectators to take to the streets? Is there a single okay way to be gay? Călin Boto’s analysis of Rosa von Praunheim’s It Is Not the Homosexual Who Is Perverse, But the Society in Which He Lives (1971) tries to tackle this issue while juggling a couple of markers: what the film meant in 1971 in relation to Berlin queer subcultures; what political cinema of the era was keen on exploring and turning around; what it means now, in a less judgmental but also more commodified historical moment for the LGBT+ community.

Historical distance is the specter that is haunting the dossier, perhaps nowhere more visibly than in Joseph Pomp’s coverage of a Tallinn Black Nights Film Festival retrospective of the films of “hundred-year-olds” (the tongue-in-cheek shout-out to nations founded in 1918). Apparently antithetical, through its title, to the festivals’ foremost concern for novelty and discovery, the program nudged its viewers to go back into the mindset of the postwar Eastern Europe, when the stakes of military allegiance were high, when films belonged to their nations rather than their auteurs etc.—and yet, the context of the sanitizing, globalizing festival space is felt in bringing these films together to contemporary viewers’ consideration, so that one Romanian film and three Baltic ones from the late ‘50s and ‘60s could primarily reveal their aesthetic qualities and arthouse influences, regardless of their individual tussles with state censorship.

This dossier is meant to raise questions and suggest connections rather than answer and solidify them, but if there are a couple of conclusions to end this introduction, here they are: 1) Read the texts, they all have intricacies that are beyond summing up in a two-page intro. And 2) Cinema has privileged access to reality, sure, but that also means it suffers the distortions, manipulations and rhetoric of what we conceive to be the world around us.