“The popular belief that gays are artistically more gifted than others is, in fact, an old wives’ tale. They only engage so much in art because they believe it makes their life more endurable. To them, art is shallow and ineffective, just like when Heydrich played the piano. As long as education and art are means of the rich and powerful to belie human and economical issues, they must be radically rejected. And as long as gays think they’re special, while they imitate the rich, they must be rejected as well.”

At least one question arises after reading Rosa von Praunheim’s lines, part of the semi-narrative-semi-manifesto voice-over of his renowned seminal film It Is Not the Homosexual Who Is Perverse, But the Society in Which He Lives (1971). Isn’t cinema part of these artistic means of the rich that Praunheim points his finger to? How come queer people should learn revolutionary behavior via the very same medium that, in the hands of the rich, “belies human and economical issues”? The answer lies in the well-known revolutionary art in general, and cinema in particular.

By 1971, radical ambitions were no news to cinema. The impressionists, followed by the early avant-garde, both Soviet and European, the American avant-garde (inter-war, post-war and the underground) and, finally, the political modernism of the ’60 and ’70, all opposed established cinema while maintaining their own formal and social call to arms that a new cinema was supposed to fit. But where does queer film stand in this history?

It Is Not the Homosexual was undoubtedly the cherry bomb of German Queer Cinema. Its rough looks and extravaganza, with a nervous voiceover barely overlapping the campy sketchy visuals of the narrative, made it a strange animal for film culture at that time. If anything, it has certain similarities to a subgroup of the New American Cinema, namely the avantgarde erotica of Jack Smith and Ron Rice, but also to the histrionic suburban comedies of John Waters and the homoerotic cheap flicks made by Andy Warhol and Paul Morrissey in the late ’60s and early ’70s. But these films had more to do with political existence than with political engagement, and their directors rarely turned against their own characters (up to some point they even seem to adore their characters and the over-the-topness of everything that’s on-screen—Morrissey’s Women in Revolt (1971) is a notably rare exception).

There were some other contemporaries of von Praunheim who had a much firmer political agenda in their work. I’m referring to the so-called political modernists, filmmakers spread all over Europe and Latin America sharing the goal of a revolutionary cinema that was anti-illusionist (in Bertolt Brecht’s view), i.e. anti-capitalist, who directed what we commonsensically know today as the counter-cultural masterpieces (bourgeois terminology!) of the time. Among others, one should count Jean-Luc Godard and Jean-Pierre Gorin, Fernando Solanas and Octavio Getino, Laura Mulvey and Peter Wollen, Dušan Makavejev, Miklós Jancsó, and von Praunheim’s co-nationals, Jean-Marie Straub and Danièle Huillet alongside the younger Harun Farocki and Hartmut Bitomsky. None were making queer films—to each his own cinema. It was the age of queer erotica, political anti-illusionism and of Fellini-esque grand-art farce, and It Is Not the Homosexual has a bit of everything. And a lot of its own. By merging distancing techniques implied in its roughness (for an imperfect queer cinema? underground heritage?), camp aesthetics and agitprop tendencies, von Praunheim was already ahead of the queer avant-garde of the time—It Is Not the Homosexual had a time, a place, and a political scope, intentions which didn’t seem to preoccupy many other filmmakers who were fighting taboos with nudity and transgressive homoeroticism.

But it was also the age of activism. The homophile movement, with its humanistic means of demanding tolerance from the oppressive society, was falling behind the queer movement. Prominently in the United States, but also in France, queer groups began the long battle of radical activism, seeking unity with the other emancipation movements. For a brief moment (’69-’75) everything seemed possible. There are many similarities between the agendas of the Gay Liberation groups from America and von Praunheim’s views. 1971 saw the rise of similar groups in Europe—a British GLF in Camden, Fronte Unitario Omosessuale Rivoluzionario Italiano in Italy and Front Homosexuel d’Action Révolutionnaire in France. It is claimed that the controversies stirred up by film were one of the reasons such groups appeared in East Germany. But what was so controversial about it?

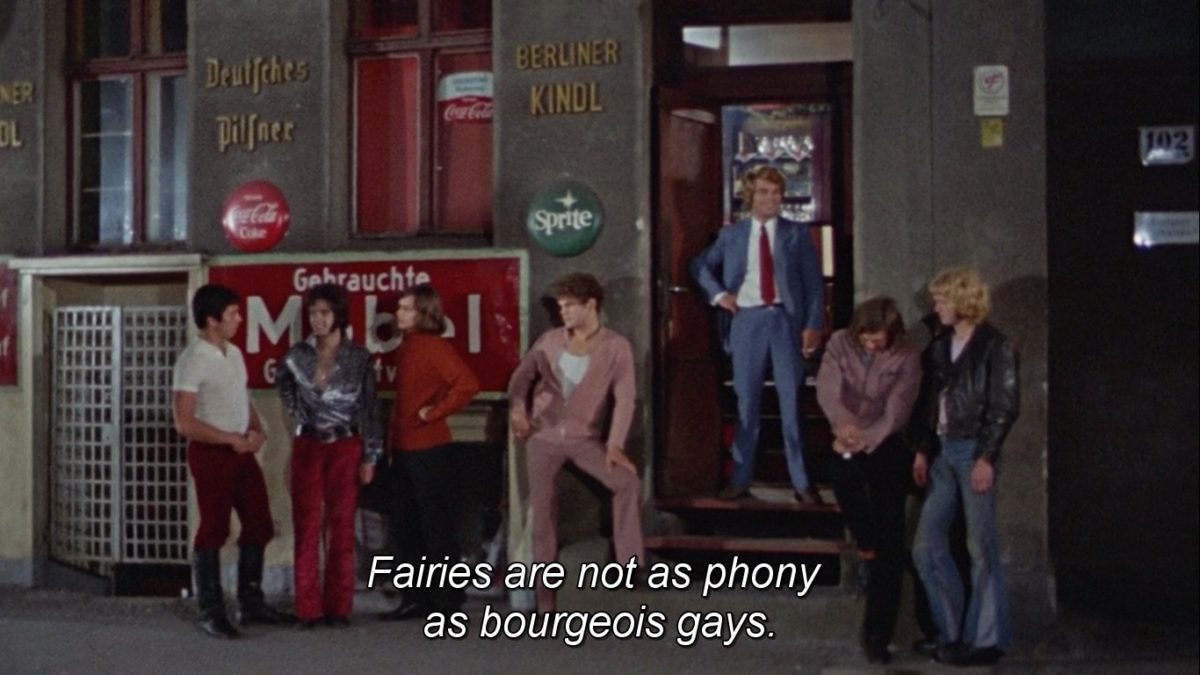

Clemens (Berryt Bohlen) is a modern prince charming of the ’70s Berlin—tall, blonde, the right middle way between twink and twunk, a bit bourgeois yet seemingly well-connected to the Zeitgeist fashion of the countercultural movement (and nothing but its fashion), carelessly wearing an unbuttoned office shirt under his leather jacket while on a date with Daniel (Bernd Feuerhelm), the new kid in town. It starts as a fling, but Clemens is not wholeheartedly interested in one-night stands, certainly not as much as in finding romantic love. And he’s on the right track: Daniel’s genuine innocence hasn’t been stained by Berlin’s post-Stonewall sexual liberation; his coming of age begins now, after coming to terms with his coming out. And there’s a lot of c*ming coming, but for one of them only.

At this point, the film doesn’t follow Clemens anymore, but switches to Daniel, who, after breaking up the domestic partnership, gets to know the ferociously erotic and self-sufficient hedonist subcultures of the queer (but fragrantly gay-centered) Berlin. Before going deeper into the movie, let’s have a close look at what’s next for Daniel, the “career queer”, since it’s relevant for both narrative and political reasons.

- After breaking up with Clemens, who seemed like an erudite to him for quite a while, Daniel is picked up by a bourgeois, art-collector type daddy. The man’s social prestige, financial means and eruditeness overcome by far what Clemens could offer. Nevertheless, Clemens is the first and last man Daniel would love by the end of the film.

- Daniel finds the older gays’ hunt for fresh flesh obnoxious and, maybe out of fear that his expiration date is close, he leaves and becomes independent, working as a barista in a gay meeting bar. There he becomes accustomed to yet another side of gay culture: hooking up—the superficiality of good looks, flirts, flings, dress codes, as the voiceover identifies. The daytime ones, that is.

- The nighttime ones, however, Daniel discovers in gay clubs. His sexual appetite increases as he becomes more normative in the one-night stand rituals.

- Soon he becomes tired of the social prelude that hooking up in clubs implies. He needs more direct, impersonal action. So he switches to cruising spots, firstly parks, and then public pissoirs.

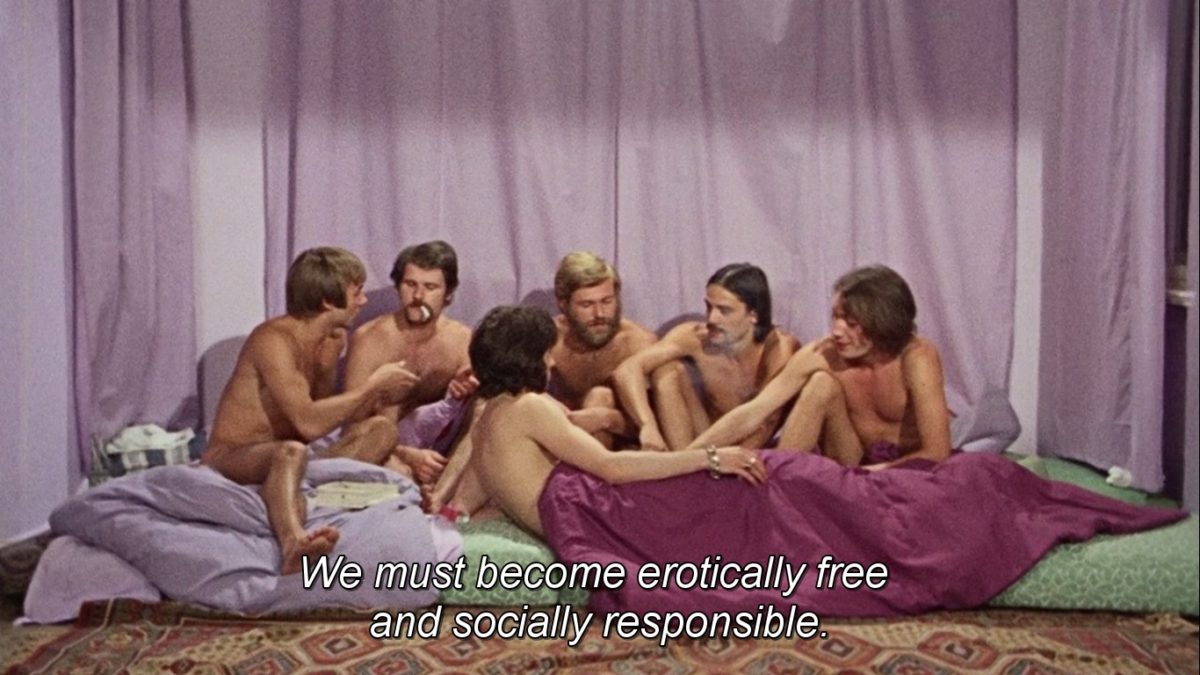

- Daniel becomes increasingly horny and sad. He finds shelter in a bar where the outcasts of the queer community get together. Here he meets an old acquaintance to whom he starts sharing his grey stories. Aroused, the guy invites Daniel to his place; it’s not what we think. The next thing we know is that Daniel finds himself surrounded by five naked men who thoughtfully listen to his life story.

Who are these men? They seem some kind of radical collective, free love and hard politics (“erotically free and socially responsible”), who deliver an uncompromising diagnosis: Daniel has been living the sugar cotton dream of a faux sexually emancipated queer. Instead of becoming politically aware of his status and making use of it, he offered himself to frivolous hedonistic fantasies, deeply rooted in meaningless concepts—sex without responsibilities, fashion, bourgeois art and education, self-destructive vices etc. They preach a new way of being queer, consisting of responsible free love, political activism, togetherness with other oppressed minorities, an en masse coming out etc. Is this von Praunheim’s ideal of queers? It surely seems so. “Closeted gays must have the guts to come out. Fairies and leather men should end their feud and fight for their freedom side by side,” they tell Daniel. “Get out of the toilets, take to the streets,” von Praunheim concludes with full-screen cardboard signs.

This is the scheme that pretends universality. However, one might be puzzled by the fact that von Praunheim seldom acknowledges the existence of lower-class homosexual men. Not the ones with a wife and kids, but the ones who do not have the money to enter a club, follow fashion trends, kill their suffering with alcohol and tobacco etc. The career queer will find his way, but what’s a poor queer to do? Neither do the five politically wise men seem to have the answer. With all the film’s anti-bourgeois ambitions in mind, a closer look would find the film pretty bourgeois itself. Rosa von Praunheim was surely not the only one unhappy with the results of the post-Stonewall sexual emancipation. Like-minded intellectuals were roaring about it all over Western countries. Leo Laurence, Guy Hocquenghem and (the sickeningly problematic) Pier Paolo Pasolini are just a few who come in mind.

Was he right? Despite not being flawless, von Praunheim’s statements and narratives seem strikingly fresh to the Grindr generation. A lot has changed during the last fifty years; homophobia diminished, but it also changed its faces and discourses. And, to fuel the resistance, so did von Praunheim in his over 100 films that were to follow this one. If his views on transsexuality were really not the best in 1971 (“The strangest among gays are, besides transvestites, who dress like women and long for female genitals, the leather men”) and if the absence of women in the film’s narrative strike as a male-centric approach, one might say that his films got politically better in time. None of which I’ve seen is as firm and irreconcilable as It Is Not the Homosexual (with the notable exception of his early-AIDS comedy A Virus Knows No Morals), but many are campy gems of queer cinema, transgressive as much as progressive. Fierce trans representation and documentation (City of Lost Souls, 1983; Transsexual Menace, 1996), redefining autobiographical films (Neurosia: 50 Years of Perversity, 1995), recovering bits of German queer culture (I Am My Own Woman, 1992; The Einstein of Sex, 1999) or uncompromising snapshots of AIDS activism (The AIDS Trilogy, 1989-1990)—von Praunheim does it all.

Now we can see that von Praunheim’s anxieties weren’t as paranoid as one might think. The queer community is better connected than ever thanks to social media, but yet politically zombified and more bourgeois than before. Homosexuality has become a market, and by making it more normative and respectable than ever, capitalism asks for its pink money. Subcultural self-segregation wasn’t the answer, and von Praunheim wasn’t ridiculing each group from the gay scene of Berlin just for the sake of it. He was demanding togetherness, the end of hierarchies and a complete break with heteronormative standards. It sounds ideal, but one should question the futility of subcultures, especially now, when we are talking less and less of gay cultures and increasingly more of Gay Culture.

What hasn’t radically changed in the last fifty years is the camp taste of the queer community. There was a moment when Susan Sontag called the homosexuals the bearers of camp, comparing them with the old aristocrats. Camp in the 21st century still has a snobbish aura, just as back in the ’60s and ’70s. In this sense, von Praunheim beat the gays at their own game. It’s not sheer irony and cynicism in It Is Not the Homosexual’s use of camp imagery, but also complicity. Pink walls, extra clothes, emphatic gestures—all the codes we still love are used against us. It’s out, loud, but nothing to be proud of. Praunheim was more right than wrong, but time proved him wrong. There never was a bad revolution, but the queer revolution did not take place. We’re on Grindr now.