Revolutions happen because small changes and reforms are no longer desired; revolutions are a plea for drastic changes. When revolutions take place, there usually follows a short period of purgatory or bliss—depending how you look at it—when nothing is clear and people live in a grey period, and afterwards the changes start at full force—again, usually—and everything changes. Anyone who has followed or experienced any revolution knows that these changes are as much political as they are cultural. In the new century, cinema—the vanguard of all established arts—undoubtedly undergoes transformation if a revolution happens. One may wonder why. The reason is that cinema—and television of course—are mass media easily accessible and stealthily powerful in affecting the minds of masses that consume them. Revolutions change leaders, political approaches, international relations and cinema alike. The Islamic Revolution of Iran took place in 1979, and in the next decade, foundations of a new “pure” cinema were laid.

Rules of the Game

For a few years after 1979, since there were no clear general rules or regulations, Iranian cinema experienced a phase of purgatory. It was a time when the atmosphere prompted political debates and the new establishment had too many other important tasks at their hands—turmoil in the Western borders, militias getting power, terrorist acts and assassinations, not to mention the start of the 8-year Iran and Iraq war in September 1980—to be able to think about cinema. During this period only some “dos and don’ts” were announced. For example, screenings of non-Iranian films—which were deemed “cheap” foreign films—were subject to some regulations; any film needed to get a screening permission from the Cinema, Visual and Audio Center and the main rules were that unreligious films, films promoting racism, fascism and imperialism, and films that exploited sex and violence would not receive this permission. Moreover, screening of Indian film was banned, except for non-commercial films, and the screening of Turkish or Pakistani film was limited and only possible when an Iranian film was being screened in exchange of that Turkish or Pakistani film.

Late 1980 brought about an important step regarding film production—the Control Council established Production Permission, which means that anyone who wanted to make a film had to receive the Council’s authorization. In short, the Control Council consists of a group of experts (including one clergyman and three experts with Islamic, sociologic and political specializations who are familiar with cinema, and one film expert) who had the following responsibilities:

- inspecting scripts;

- scrutinizing directors and actors so as to verify that they are not personae non gratae;

- observing the production phase;

- observing the post-production phase;

- ensuring the last inspection of the finished film and subsequently issuing the Screening Permission.

1983 was the pivotal year for cinema regulations and transformations. Early in the year, concrete regulations were introduced by the Ministry of Islamic Culture and Guidance. Accordingly, it was decided to produce more Iranian films so that the need for foreign films was eliminated. Any film that shook Islamic beliefs or profaned Prophet Mohammad, Shia’s twelve Imams or the Supreme Leader would be banned. Any insult towards Islam and other recognized religions in the Constitution would equally lead to banning the film, as would promoting racism and social polarization, female objectification against Islamic rules, sexual abnormalities and deviations, and stimulating depiction of any kind of violence. An important provision of this regulation made it possible that a movie with Screening Permission could later be banned for any reason by different cinema organizations of the Ministry of Islamic Culture and Guidance. In other words, films could be censored or totally taken out of cinemas, regardless of whether they were made by newcomer filmmakers or established ones.

This regulation, which has not changed drastically through decades, definitively shaped Iranian cinema after the Revolution, together with Fajr Film Festival and the Farabi Cinema Foundation. The festival, first held in 1983 as a national film festival (with foreign film sidebars from 1989 onwards) became an international festival in 1995, thus shaping Iranian cinephiles’ perspective of global arthouse films. The Foundation, also founded in 1983, held the monopoly for more than two decades concerning Iranian film distribution and promotion in festivals abroad. It is important to note that key figures of the Fajr Film Festival and Farabi Cinema Foundation were current or ex-members of the Iranian Organization of Cinema (founded in 1979) or the Office of Cinema, both sub-offices of the Ministry of Islamic Culture and Guidance who only rotated their positions. Thus, Iranians’ impression of world cinema and the world’s impression of Iranian cinema could now be submitted to airtight regulation.

Whatever Happened to FilmFarsi?

The main trend of Iranian cinema before the Revolution was FilmFarsi. Houshang Kavoosi, a demanding film critic who studied cinema at IDHEC in Paris, coined this word. He first used the word in the early 1960s and bashed almost all Iranian films for their overall lack of originality and flaws. FilmFarsi was a formula based on Hindi, Turkish and Egyptian films screened in abundance before the Revolution. Its main elements were women singing in cabarets, men fighting in cafes, cheap love stories with mostly PG-13 and, rarely, R-rated sensuality, and—most importantly—cliché scripts, sub-standard technical execution and flawed directing.

As the majority of films made in Iran before the Revolution were FilmFarsi, what happened to those involved in their production, and film production in general? It is a long and sad story, but in short, most actresses were banned from acting, major male stars were also ousted from their trade, as were some directors. As a result, a number of actors and filmmakers left Iran, especially on the eve of the Revolution and within a short period after it, fearing for their lives and taking on the role of exiles around the world.

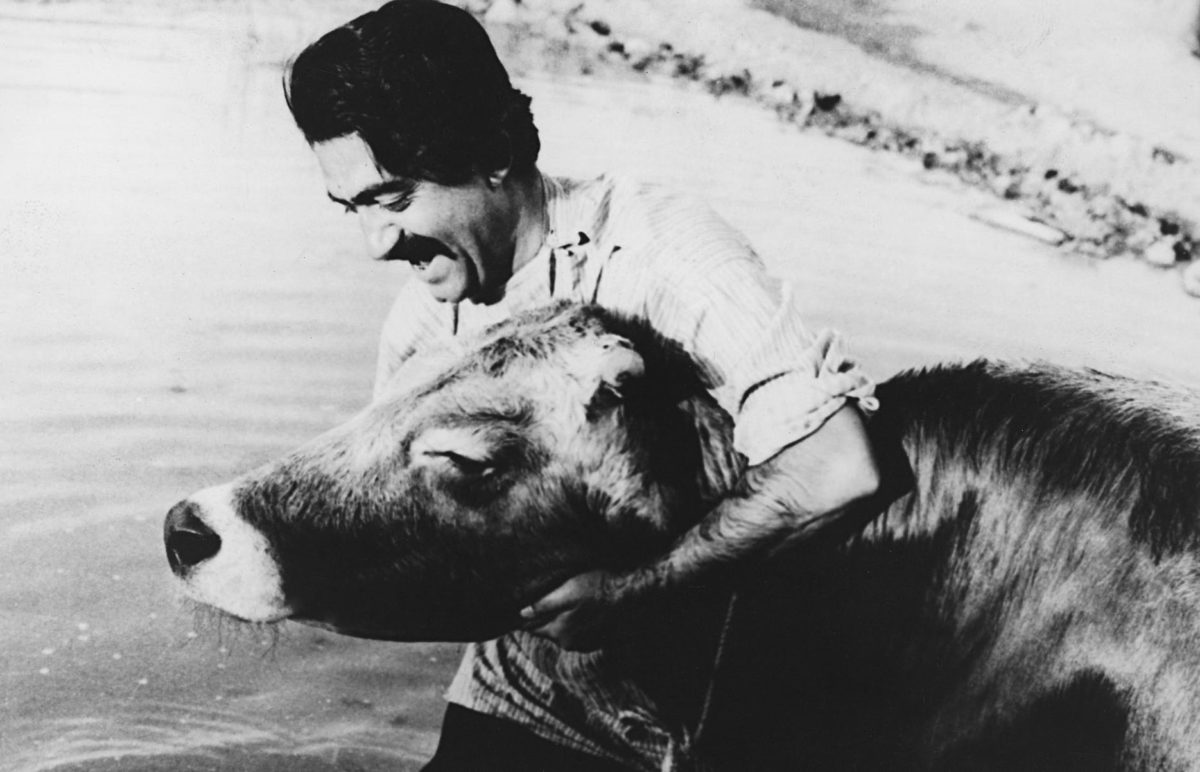

It was only in the spring of 1980, after Ayatollah Khomeini watched The Cow by Dariush Mehrjui and considered it better from a pedagogical point of view than non-Iranian films, that filmmakers realized it was once again safe to work in cinema. One may ask: why this particular film? There are a number of reasons, most prominently that The Cow has no “impurity”, there are no dance or cafe scenes and women—while having almost no role in the film—all wear hijabs. A more thematically informed reason is that this symbolic film is about villagers who have nothing but their lands and cows and when they lose any of them, they succumb to alienation and, finally, madness. The film is an allegory for the purity of simple life, contrasted with the modern life of the landowners we barely see. In other words, the film works both thematically and practically with the “purity” which was in high demand.

This “new” cinema assumed the goal of saving Iranians and evading the exploitative cinema of the West. As a result, those who stayed and were pardoned—some through public denunciations of their activities before the Revolution—started working again. Masoud Kimiai, Dariush Mehrjui, Bahram Beyzai, Abbas Kiarostami, Amir Naderi and Nasser Taghvai are among the filmmakers who continued their career after the revolution (though Beyzai and Taghvai experienced so much hardship that the latter stopped making films and the former went in self-exile in mid 2000s). Interestingly, neither of the mentioned filmmakers were FilmFarsi directors and Kimiai, Mehrjui and Taghvai, more inclined to art-house cinema, are known as the founders of the Iranian New Wave. The rest of the 1980s were crucial for establishing the new identity of Iranian cinema. It is the time that making war films became prevalent both as a result of the ongoing war between Iran and Iraq and as an effective tool to establish revolutionary doctrines. Ebrahim Hatmikia, Rasoul Molagholipour and Hamidreza Darvish were the main figures behind these war films, belonging to a genre called “Holy Defense Cinema”. It is worth mentioning that, with the changes sparked in the mid- and late 1990s, this cinema, which was more prone to propaganda, gradually turned towards a pacifist stance.

At the same time, the cultural institute Hoze Honari (the name of which is derived from Hawza, the school or Islamic Clergy, and Honari, which means “artistic”), established in 1979, found its way into cinema. Mohsen Makhmalbaf and Rasoul Molagholipour, two of its most important affiliates, were looking for “pure” cinema and their early films in that period shows how loyal they were to the thoughts of a cinema which does not follow a Western model and instead promotes Islamic and revolutionary creeds. It is also worth mentioning Hoze Honari later got involved in film distribution, inside Iran and abroad. They are by now a leading film distributor, even owning a number of cinemas in Iran, and they systematically refuse to screen in their cinemas films which do not adhere to their ideological doctrines, even when those films previously obtained Screening Permission.

It is at this time that Abbas Kiarostami made his groundbreaking film Where Is the Friend’s Home? (1987), with the support of Farabi Cinema Foundation and the Institute for the Intellectual Development of Children and Young Adults (which produced numbers of films by Naderi, Beyzai, Kiarostami and even Mehrjui). And thus began the conquest of world cinema festivals by Iranian cinema. Where Is the Friend’s Home? is the kind of poetic, humane film that post-Revolutionary promoters of Iranian cinema sought after. The cinema of Kiarostami and its followers seemed like a safe ground where even Hoze Honari members like Makhmalbaf could play, and new talents like Jafar Panahi could also get involved in. (How these leading figures of Iranian cinema became the personae non gratae of Iranian cinema is another story.)

But why did international festivals and cinephiles around the world open their arms so warmly to these films? They were coming from a country that not only had a new ruling government that had toppled its US-UK-supported Shah, but was also reluctantly involved in a fight with its neighboring country—one supported by almost all Western countries—for more than 5 years, and was (and still is) very different from its neighbors. A country so curious that you can call it exotic. This exoticism, combined with a distinctive cinema—called poetic and still living up to its name—that was dealing with such humane and universal subjects, made efficiently with minimum resources, was like a breath of fresh air in a historical period when cinema was passing through hard times, when no relief was within reach. If you look back at 1980s cinema, you can see no word better than “decline” to describe it: Hollywood had passed its golden age, the revolutionary French New Wave of the ‘60s was losing its edge, and it seemed Western cinema, if we want to be a little brutal, had nothing new to put forth except sci-fi films. Moreover, orientalism and looking at the East were major topics for major thinkers—Michel Foucault for example wrote on the 1979 Revolution—so everything was working in favor of the Iranian filmmakers to allow them to seize the moment and burst onto the world cinema scene. Luckily, they had a number of tricks up their sleeves.

Triumph of the Cinema

What was the result of all these new regulations and criteria? Apart from a number of propaganda filmmakers, art-house filmmakers found ways to sidestep making propaganda films. How? By making a local version of Italian neorealism—a kind of cinema already popular in Iran before and after the Revolution. A cinema cherishing the universal values of humanity, kindness and resistance against suppressors. These values were also shared by the key figures of different cinema organizations of post-Revolutionary Iran. The most significant director of this period is of course Abbas Kiarostami, who both paved the way for Iranian films to be internationally recognized and supported many other filmmakers including Mohsen Makhmalbaf and Jafar Panahi to establish their own way of expression. For many years, it seems that all these filmmakers were influenced by neorealism and only now, when looking at their oeuvre in retrospect, you can see their gradual departure from it. The architects of Iranian cinema after the Revolution were not aiming to eliminate the art of cinema, it seems they wanted a cinema that amplified the values of the revolution, as if cinema is like a ministry. Were they successful? It is not the aim of this article to judge that. What is clear now is that the exemplary films of 1980s and early 1990s are not war films or political films; they are arthouse films that adhere to universally shared values of humankind.