There’s been an intriguing, codependent relationship between filmmakers and film critics ever since people picked up cameras and started to shoot. Though the first name that comes to the average film viewer’s mind when “film criticism” is mentioned is usually Roger Ebert, seeing that he was born in 1943, it is indisputable that he couldn’t have been the first film critic ever. More accurate names for the foundations of American film criticism might be Frank E. Woods, Louis Reeves Harrison, Epes Winthrop Sargent, and for the British, Walter C. Mycroft, Ivor Montagu, and Iris Barry. As years went by and film attained a more serious artistic status, the pursuit of film criticism acquired a better social standing. Many critics kicked things off in criticism only to find themselves on the other end of the spectrum eventually. Think Francois Truffaut, Jean-Luc Godard, Claude Chabrol, Éric Rohmer, and Jacques Rivette, all of whom were representatives of the Nouvelle Vague of the 1960s, but who also wrote for Cahiers du Cinéma, a French film magazine co-founded in 1951 by André Bazin.

Regardless of what type of film criticism one enjoys writing or reading, its objective is to shed some light onto the seventh art. Just to shake things up a bit, one could wonder, can their assigned roles potentially be reversed? Is there a chance that perhaps film as a medium can provide insight into its verbal evaluation? A critic may be assigned to a piece in a plethora of different ways. Be it a review on a private blog or a YouTube channel, pitching an idea to a print or an online editor, or being provided a film festival press pass which usually means reviewing the official competition lineup, strict rules don’t apply. But, what happens when the assignment comes in the form of “write whatever you want to write about at the moment. What interests you the most right now?”. Besides the obvious care this unnamed editor has for their writers, something else may be faintly discerned: this type of collaboration fosters and values freedom.

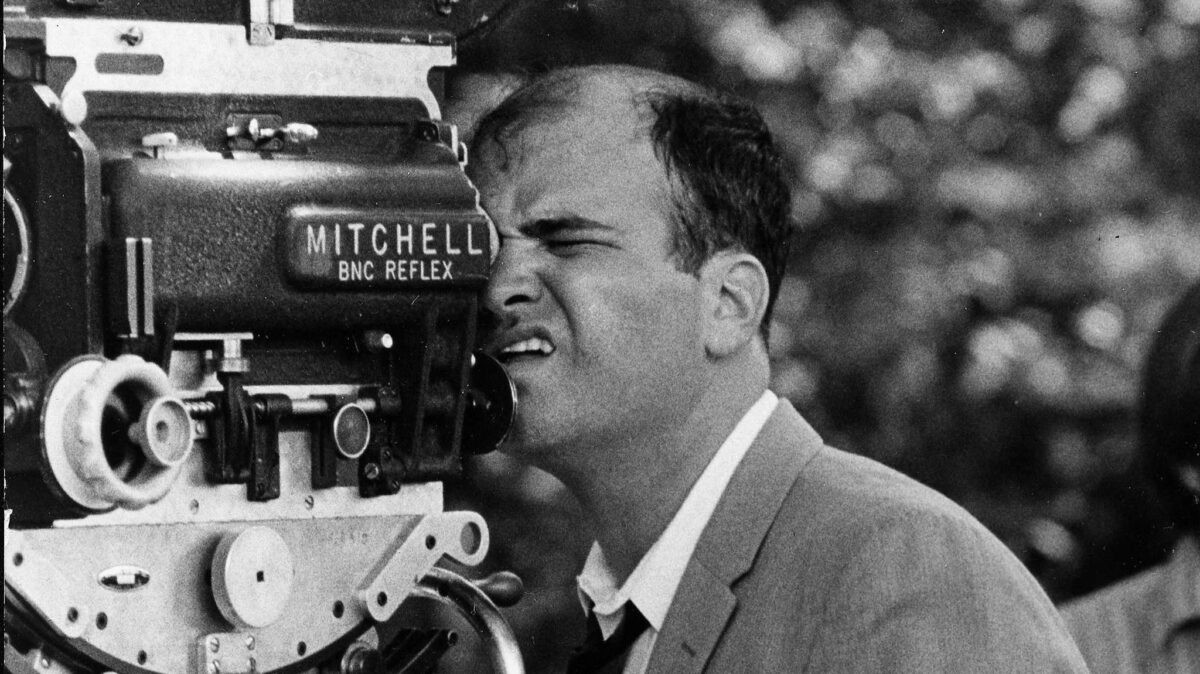

Which begs the question: what happens when freedom and curiosity take the wheel of this pen-forged voyage? This was in fact the question that gave birth to this particular piece. In an attempt to answer this aforementioned query, a need was created to not only pinpoint a director whose approach to filmmaking takes liberties with traditional narrative forms and consequently desires to explore paths beyond the common and conventional, but also to focus on films that are preoccupied with the manifestation of emotions and ideas that propel the movie forward rather than plot and character development. With that in mind, there was one filmmaker whose career seemed to be a pristine example of these prerequisites: Terrence Malick, a Harvard philosophy graduate who entered the filmmaking game somewhat later in life (born in 1943, so almost aged 40 by the time his first feature film was released).

Quite the idiosyncratic figure, Malick undeniably has developed a very unique style when it comes to his shooting methods, which by extension has an effect on his overall aesthetic. Favoring the use of wide angle lenses (even for closeups), natural light, steadicams, and poetically ambiguous voice-overs, his distinctive signature has elicited a sort of love/hate response in both moviegoers and film industry professionals alike. As interviews with the director are nearly non-existent and the ‘madness’ behind his craft is never revealed, one draws conclusions by picking upon the cries and whispers of his colleagues. For instance, Martin Sheen, one of the leads in Malick’s debut feature Badlands (1973), has stated in one of his interviews that upon meeting the director he knew that he was talking to a genius. One could argue here, however, that Malick’s unusual filming habits started to fully take shape after the release of Days of Heaven (1978). With two successful projects under his belt, Malick was offered by Paramount a million dollars for the next one, no matter its subject matter. The filmmaker began fostering a passion for shooting a film about the emergence of life on Earth; a film that in due course was titled Q. Time went by and Paramount received no official production start date nor a script. Instead they found on their doorstep a fair amount of pages filled with lyrical imagery, but no story. With Paramount’s growing uneasiness came a time that Malick, exasperated, decided to abandon the project and as it would seem, filmmaking altogether. A long period commenced during which Malick remained unseen by the big Hollywood eye. Approximately 20 years were marked by his absence, while he lived in Paris with his second wife though rumors had taken him even for dead.

A borderline urban legend up to that point, Malick began development of The Thin Red Line (1998) with a script and a bunch of big Hollywood names, many of which were supposed to fill the screen for the entirety of the film, but ended up being mere secondary characters. As Christian Bale has stated in a promotional interview for Knight of Cups (2015): “Anyone who gets involved with a Terry film knows that [they’re] either not in the film or [they] might be the lead in the film. It could be one or the other.” Of course, such a loose grasp of one’s presence in a project isn’t for everyone. Adrien Brody and Christopher Plummer have vowed to never work with Malick again after their respective collaborations with him on The Thin Red Line and A New World (2005).

This initially unplanned cut leaves his collaborators surprised by the eventual results because Malick’s films become a unified whole in the editing room; a method that requires an immense amount of footage to be collected, most of which gets the ax. Gradually, the same fate would be met by his scripts from The Thin Red Line onwards, as he started leaning on improvisation, leaving behind the typical causal, and character-driven plots. In their stead came films centered on ideas, themes, and emotions which were inspired by his real life experiences. Though this style that portends a markedly poetic look on subject matter that is both philosophical and universal was being molded for years in collaboration with cinematographer Emmanuel Lubezski among other industry professionals, the paradigmatic example of this aesthetic development is the so-called Freefall Triptych trilogy: To the Wonder (2012), Knight of Cups, and Song to Song (2017). Here Malick takes a leap of faith, if you will, in that he pushes various limits during production with his innovative and distinct voice. Actors are given character descriptions instead of scripts and they’re often directed to let emotions unravel via a physical expression rather than a linguistic one. This way, everything is in flux, and so to place it within the frame, Lubezski’s camera is always in motion; a kinetic, silent, and invisible dance partner that flows from face to face and place to place.

A semi-autobiographical trilogy whose point of convergence isn’t plot or characters, but theme and aesthetic, the Freefall Triptych is an exploration of a pure form of humanity preoccupied with its fragmented sense of Self. This is a quality that has rendered people powerless in piecing together the remnants of their individuality, which gradually became endemic to the human experience as a direct consequence of the alienating forces of modern society. Perhaps this is why at the core of each of these films is a constant need for searching. Characters ceaselessly wander in locations that keep changing, unable to stop. This reflects back on Malick’s approach to filmmaking: he begins with questions and embarks on a visual journey seeking for answers instead of breathing life into a predetermined project. In other words, these are films not mapped out in advance, but shaped by reaction—a reaction to an actor’s impromptu stroll, to the natural environment as the camera pans upwards to capture a flock of birds, utilizes the perfect natural lighting of the sun during magic hour, or even follows around a butterfly that’s aimlessly flying until it incidentally lands on an actress’ hand. Prior to the Freefall Triptych, these improvisations were employed as pieces of a montage or transitions, but later on, they evolved to primary scenes—building blocks stacked together side by side to create an absurdly consolidated entity during the editing process. Ironically, then, Malick succeeds in what these characters fail to do time and again: collect bits and pieces, match them together in harmony, and complete the puzzle. This type of collaboration between industry professionals and the natural landscape may be described as pursuing moments of truth. The trilogy, then, may be construed as an exploration of reality via a lens of sheer authenticity; a meditation on existence or maybe a manifestation of absolute realness.

“I was desperate to feel something real” says Faye, Rooney Mara’s character in Song to Song—could it be that Malick was sensing the same horrible hopelessness? It’s almost as if he’s trying to recreate his life as organically as it can occur with as much unpredictability as can be afforded. Real life, after all, is unpredictable: like dipping your co-star in the waves of the ocean and she—surprised—laughs. To the Wonder, for instance, touches upon his personal life during the 1980s-1990s as Ben Affleck, Olga Kurylenko and Rachel McAdams function as sort of stand-ins for Malick, Michèle Morette (second wife) and Alexandra Wallace (third wife) respectively. The central theme of this film is love and the adversities one faces while building a relationship with someone else who’s so distant and taciturn that they’re nearly a void; an empty vessel. Knight of Cups echoes, almost in a behind-the-scenes manner, Malick’s experience of working in Hollywood back in the 1970s as a script doctor. Framed by the “Hymn of the Pearl” from the Acts of Thomas, the audience attempts to follow Rick (Christian Bale), i.e. the knight, a man lost in the vanity and extravagance of Hollywood, almost damned by his success in that he cannot find his way out of its immense nothingness. Song to Song seems to combine the two aforementioned themes as Faye, BV (Ryan Gosling), Cook (Michael Fassbender) and Rhonda (Natalie Portman) are trapped in the music scene in Austin, Texas, aimlessly moving around each other driven by desire and love, incapable of drawing to a halt. Palpable bits lived day by day make it on screen fictionalized and display moments of profound truth and utter vulnerability.

One could wonder at this point, “why Malick?”—there are many filmmakers that go into uncharted territory when it comes to shooting techniques and/or aesthetics, so what is it that makes this particular individual noteworthy? Besides taste, the answer really comes down to Malick’s hybrid status. He took his first filmmaking steps within Hollywood walls, figured out it wasn’t a good match, and vacated the premises. He then returned with a set of rules that were not to be questioned—take it or leave it. In this way, he has managed to modify the filmmaking game to his liking and in doing so, he has both the perks of working in Hollywood and the independence that’s usually intolerable within the system. This freedom has allowed him to father a distinctive style, which he kept on developing despite the backlash he had to face. Perhaps the same conclusion may be drawn for critics that have unavoidably started by following mainstream rules—write about sexy topics that will reach the maximum number of readers. Is it February? It’s all about the Oscars. Godard just died? “Isn’t Breathless (1960) one of the best feature film debuts?” And the list never ends. But it’s not about denying the benefits that the list provides; it’s about finding the voice that will not only grant one the film festival advantage—among others—but also the ideal space to experiment with form and content. While typing away, trying to reach this goal, the time may come that the words written will compose a secret. Instead of keeping it under lock and key, one decides to transmute it online, just a click away.

Perhaps, this is where the essence of true film criticism may be detected—in that it has the capacity to be about something deeply intimate in the same way Malick’s films are. Considering that this varies depending on the ideological and aesthetic values of each writer, the common ground is the eagerness to really peer into something from an unorthodox angle. To get to that perfect draft, one has to pour out countless words, shape them into paragraphs, only to find that, alas, they may potentially make no sense at all. Unavoidably, much of this supposed typed footage will have to be cut out by an editor. With each step taken, and if the writer dares to make it personal, i.e, making oneself feel exposed, the end-result has the potential to be an eloquent excursion with a meaningful impact led by unresolved questions. If it isn’t about attempting to have an intense emotional and/or intellectual effect on someone, what is the point of film criticism, if at all?