An incredibly large proportion of Bazaar Sitaram is distilled through strict geometries: the structure of its telling resembles a set of concentric circles wherein the fiction at its nucleus is shrouded within layers of ethnography, cultural commentary, a historical lesson; it renders the conflict between tradition and modernity as ultimately, the discourse between a spiral and a line; its camera charts trajectories along the sharp contours of the various buildings that constitute its location, and finally, the film’s central speculation manifests as a love triangle between its two protagonists and the city they reside in. This should not be surprising in and by itself since Bazaar Sitaram is, after all, a film about a place. The act of architectural mapping rests at its heart—and yet, unlike a diagram, whose shape is often fixed and immutable, the film’s own being is permeated by a state of perfect flux. It moulds and remoulds itself throughout its duration; it starts off as one thing, becomes another, then a third, and then is restored to its original condition.

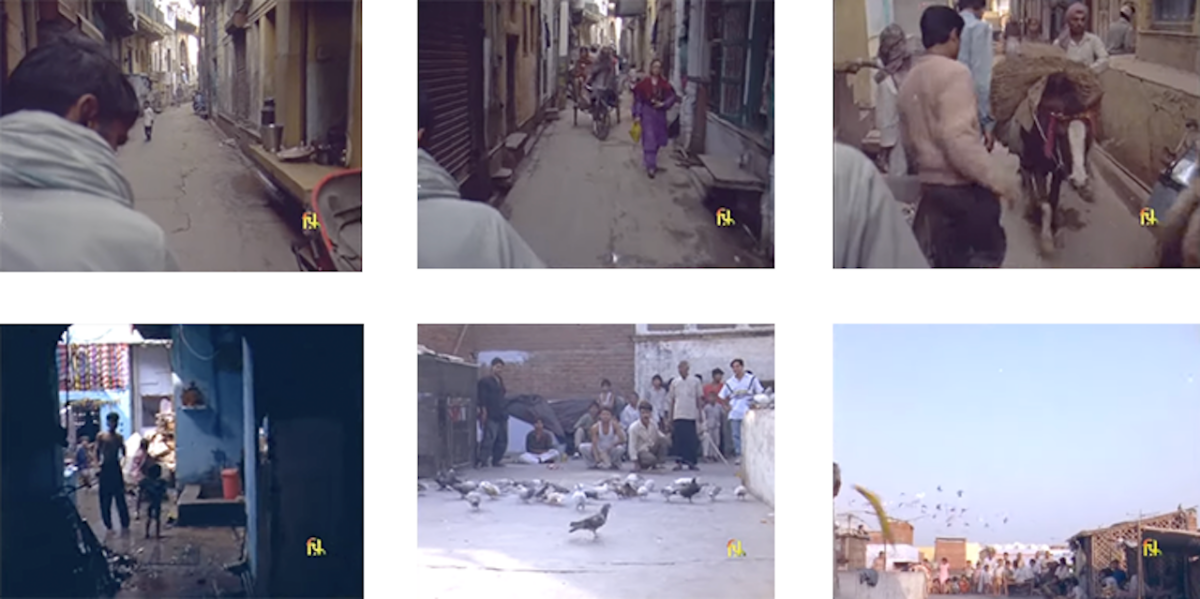

When thinking of his cinema, but also cinema in general, Miguel Gomes mentions that it is the “intrinsic frictions between its diverse moving parts that define the medium”—at its optimal, a cinematic text exists in a state of a continuous becoming. Bazaar Sitaram is a film about perpetual mutation: it tells the story of an ancient bazaar in Northwest Delhi (“some of the shops here have been around for over a hundred years”, exclaims the film’s protagonist, played by its director, Neena Gupta) which is under siege from the transformative effects of the city that surrounds it. It presents the market—and the various residential compounds that are embedded within it—as an island with an intrinsic canon of codes, ceremonies, prescribed rituals and mores, but which must prepare to contend with inevitable upheaval enforced upon it by the world outside of its borders. In order to depict this universe of slippery surfaces, the film assumes a form laden with startling alchemies: its opening image belongs to the tradition of cinema verite, which then gains composure to mark a shift to fiction, which includes anthropological indices in its crevices, and is abstracted ultimately to a static, poetic lament.

Such gross malleability lets it emerge as a film populated by distinct temporalities. Produced in 1993, it presents itself as a record set very much in the era of its making, and yet, pungent with lament for a time long gone. This holds significant meaning, for the film was released at a verifiable junction of tremendous change within India. In 1991, the central government headed by Prime Minister Narasimha Rao introduced economic reforms in the country that were pioneered by his Finance Minister (and later, Prime Minister) Dr. Manmohan Singh. This intervention would wreak an open season for liberalization: state control began to loosen, the market acquired new sovereignty, privatization soared, foreign brands began to set up production units in India and the consumer economy entered its first throes. While the move marked a clear rupture from the socialist dream upon which the freshly independent republic had been founded two generations ago, it also induced within larger society a cultural zeitgeist: we laboured under a drastic anxiety of loss; the older methods of existence seemed on the cusp of extinction, and the true implications of those that would replace them were still unknown.

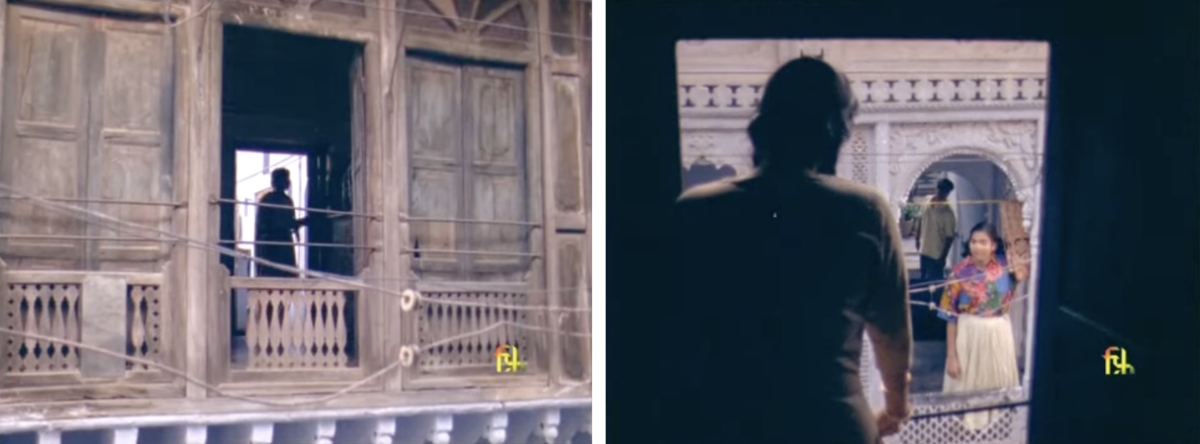

Gupta’s directorial effort—her only one in cinema before she returned to television with the episodic teleserial, Saans (Breath, 1998) and then, two decades later, as a character actor in contemporary Bollywood—exists as a perfect summation of the tensions that populate a moment of grand transition within any nation’s history. In order to depict this inevitable tussle between yore and its impending substitution, Gupta, who also wrote the film, plants an archetypal love story at its heart. Within the actual environs of the marketplace, Gupta inserts the fictional narrative of a developing engagement between an any-girl of the locality (which she plays) and another, any-guy from the neighbourhood (actor unknown). They conduct their romance through a toolbox of cliches sourced from cinema’s long history of the genre: stolen glances, secret notes, clandestine meeting spots, private cordons in a public space—that nonetheless work precisely because they are familiar. In a way, thus, Gupta allows the film to assume a fable-like nature by installing within it clearly demarcated, genre-based iconography: the tryst between the lovers becomes an analogy for that which is eternal and recognizable; its origins traceable to a distinct lineage.

It is fascinating to note that Gupta’s film was produced by the Films Division, a government organ that has remained, since its inception, a symbol of the existential confusion that marks the Indian state’s relationship with cinema. As a result, a successful historical account of Films Division does not exist within the catalogue of films it has produced, but in the various attitudes that permeate their undertow. Conceived in 1948, Films Division was initially tasked by the Nehruvian Government (which had inherited Gandhi’s view of cinema as a form that is valuable only if it is of “some utility to society”—but then gave his staunchly moral view a social twist) to produce propaganda newsreels or film magazines that would act as a way for the government to inform its citizens about the various schemes or programmes it had launched for their benefit.

When the unit installed Jean Bhownagary, a multimodal artist, as its Chief Producer in 1965, its history began to be enveloped in fantastic mire. He helped usher—as its primary reformer as well as the chief commissioning authority—a spate of films that were subversive, vehemently political, employed avant-garde techniques, and negotiated consciously with the conventions of documentary. This ‘movement’, spearheaded by filmmakers such as Pramod Pati, S N S Sastry, S Sukhdev—but which also included other prominent practitioners of Indian artistic cinema such as Mani Kaul, Kumar Shahani and Adoor Gopalakrishnan—would effectively continue until the late-1970s. At this point, a shift in the government’s larger inclinations caused it to rein in the organ’s output (this process of moderation would repeat in the case of the National Film Development Corporation (NFDC), the chief provider of funds for the films of the so-anointed Parallel Cinema Movement, and which would pull its support in the mid-80s, causing various projects to cease abruptly). By the early 90s, therefore, Films Division existed already at the verge of a nomological despair—its struggle to justify its own presence would reach a logical conclusion with the merger of the organ into the larger super-body of film as imagined and constituted by the central government in 2022, when Films Division, National Film Archives of India and the Directorate of Film Festivals would be subsumed into the NFDC.

Bazaar Sitaram’s opening shot—an extended document that tracks a lane in the marketplace from atop a rickshaw—is accompanied by a self-reflexive narration in Gupta’s voice, in which she describes the milieu of the film to the audience, but which ends with a strong statement of purpose: “apni jagah, apna mohalla, apni kahaani banane ki ek chaah.” (Translation: “this film is an attempt to tell one’s own story, set in one’s own location.”) Such an announcement of autobiographical intention is significant for two reasons: the first, because it delineates a decidedly personal desire within a project commissioned by the government, and second, because it is a direct comment on a long period of relative sterility within the films produced by the Films Division. Ironically, the state would attempt later to redomesticate the project by rewarding it the National Film Award for Best Documentary, which is an odd categorization for the project, but also registers as a tribute to the many skins it sheds and rewears during its runtime.

One of Bazaar Sitaram’s chief accomplishments as a film is indeed the definitional collapse it induces within the narrative of Indian film history, which has remained, as indices go, swift to categorise, label, organize and capture. The absence of any easy strata to which it can be exiled may also explain why it could never be canonized, or why it is largely forgotten. It is neither pure documentary, nor real fiction, not entirely speculative but features at least a proportion of fantasy. It is also rendered through artistic choices that afford the film the luxury of concurrently existing at the vertices of a diverse set of film movements. Gupta borrows from the Parallel Cinema its inclinations towards realism and a penchant for commentary; from the films issued by the state a tendency towards ethnographic profiling and milieu construction; from experimental film its freeform structure and eye for ultralocal eccentricity, and from the narrative film a series of genre-codes that preserve a memory of themselves.

In order to depict the romance that is settled at its heart, the film employs a crucial gesture: whenever the lovers spot each other from across the terraces, the eaves or the lanes, we can see their lips move in order to mouth words, but we can never hear these. The film recognizes these—as is true for any other totem of genre—as references to themselves; there are no new lines that the lovers can utter, there are no phrases that will emerge from this pair that we have not heard from any other. They are, after all, the facsimile of all the lovers that have preceded them. Their tale, therefore, becomes, for Gupta, a method by which to install within the film a regime of the familiar, a stream of the seen—until she begins to affect it with slow subversion.

Within a pivotal moment of the romantic story and thus of the film, our hero uses the opportunity of the bluster and sound of Diwali, a major Hindu festival that occurs at the beginning of each winter (the film assumes its cyclical nature by aligning itself with the annual passage of seasons) to plant a surreptitious kiss on the cheek of our heroine. Stricken by shame, she isolates herself and decides to sever her interaction with him. This marks a deep rupture within our love story—for a physical expression of desire in a conventional romantic film would be natural, but within Bazaar Sitaram, it causes significant turmoil. It introduces sexual tension to a seemingly innocuous tale of young love; corrupts it, adulterates it, makes it dangerous. The love story—which exists in the film as a token of predictability—suddenly becomes disorienting and uncanny. This is not unlike the other upheavals that are crystallised within the film: of the city that surrounds the market, of the country in which it is located, of the attitudes that define this country.

This is one of the most recognisable features of Bazaar Sitaram, in that it remains a film with a displaced centre; fluid, very ductile—in a state of active discourse with its own artifice. Gupta’s own approach is to embrace contradiction, to put on display its own dithering. Its subjective, feminine telling of the archetypal love story lets it alternate between an ongoing celebration of tradition and a pungent criticism of it. Gupta litters the film with an exhibition of performances of religious ceremonies, populated in general by women who sing in praise of different deities (these are the most visible monument to its ethnographic desire—Gupta, who also designed the soundtrack, records seemingly actual people to elevate the film’s nature as a document). The love story that is resident at the nucleus of the film is surrounded—inundated—perpetually by distinct traces of an omnipresent society . Bazaar Sitaram seems to recognize the conservative as a safe refuge from the adventure intrinsic to the youth of the lovers—whenever their romance becomes too outrageous, the film returns to the abode of the traditional.

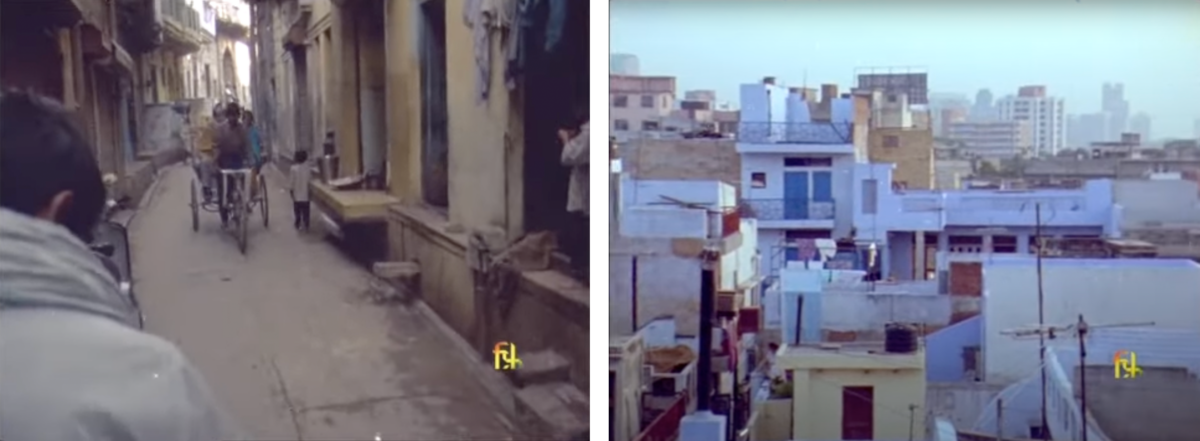

And yet, it also observes the oppression inherent in this axis—near the film’s close, the film’s heroine subscribes to the hero’s brave offer of elopement. She leaves the locality to wait for him at a street-divider from where he would have told her he will pick her up (this is also the only time in the film that we see the city outside of the market—shown as one may predict, as an unfamiliar, sinister space, bathed in night). However, he does not turn up, since his parents have agreed to marry him off for an enormous dowry. The same traditionality that is revered earlier in the film also becomes a harbinger of the greed that now infects the mold of the film’s little universe. Gupta uses the hero’s eventual abandonment of the heroine—an upturning of the conventional expectations of the genre – as a way to parenthesise the loss of innocence that is the film’s central theme. In this, Bazaar Sitaram assumes an air that is concurrently eternal and timely. It is about a settlement whose hermetic enclosure has sectioned it off from the changes of the world outside of it, and yet, there is in the film the constant ringing of a cautionary note about an upcoming overhaul. Ultimately, Gupta’s film contemplates the various dilemmas that abound within a milieu in a state of confusion, for even though it may appear familiar, it is now infected by influence alien to it.

In the epilogue, the heroine returns to the locality. When we spot her apparition for the final time, she rests defeated against a pillar on the terrace of her home. Through the open window of the house across the street, she is witness to the marital ceremony of her erstwhile lover. The romance is dead. A few moments later, as the camera roves over the skyline of terraces and roofs of the bazaar, one can see the city in the distant background—a tireless monster that looms in the horizon—and the voiceover confesses the ambivalence that is the film’s overarching sentiment, “…if the roots of the tree are well entrenched, it can flourish; but it may also die.”