January 7

We all had nightmares during the first full moon of the year. We tried to let go of this by writing them down on paper and throwing them into a fire late last night. The lights keep going out and back on in this train carriage. I am dreaming a lot these days. Water dreams, omens of birds… “What is coming?”, I wonder…

When I spent Christmas 2022 in Cambridge, I described the city as “so unlikely” in my diary. My companion and I, in our own way, were prisoners in that house, that city, on that island. I spent the days doing the most mundane of actions: reading, cooking roasts and breakfasts, reading and watching films; our backdrop a somehow comfortably liminal space in between 2022 and 2023 in which longer days were finally on the horizon. It was my first Christmas away from home.

I decided at that time to give into my very sudden obsession with water that I had caught, or that caught me, by worshipping its images. Filmmakers portray something that is essentially see-through. How can the presence of something crystal clear be so elusive? I had some visions of water. Maybe wells to dive into. In the original Irish myth the girl survives. It’s a risk worth taking. I remember now. In Cambridge I was told that the Irish have a mythology rich with stories about wells. We had gone off topic after discussing The Quiet Girl (2022). Many of the tales are double in meaning, as warrants to keep off children wandering too close to the wells. Until somewhat recently, these were a main source of clean drinking water for both animals and humans in Ireland . In one story that stayed in my head for days, a girl falls into a well and clogs it, resulting in the well overflowing and eventually turning into a river.

However, my companion emphasised that in the original folk tale, the girl survives and becomes a goddess of the water. Many Irish believe wells have magical and medicinal properties. I don’t think we all become sacred thanks to our bedside glass of water, but in that element is a force that envelops us even before birth. With its pushing and pulling, it characterises our desires. With its cheer magnitude, it reveals something about our search for clarity, as we peer into the deeply unknown.

January 13

In my dream last night I was in deep water, afraid to cross into a shallower bank. A dragon slithers by. Later that day we went searching for an altar, but instead found the air in the chapel thick with Myrrh.

I have no idea how I stumbled upon that gem from 1896. But there was that little boy, standing indecisive just above Les bains de la jetée des Pâquis while his companions were quickly jumping in and climbing back up, like the rods on a watermill in rotary motion. Leaking water out of their trousers.

In Kong’s Finest Hour, Alexander Kluge describes the Boulevard Principle. “The principle of moving between certainty and fantasy, narrating stories based on real events.”

In Aftersun (2022), Charlotte Wells narrates the story about the pain of being too young to understand. Memory crashes from the depths of the mind into the forefront,just like waves, some larger and more unexpected than others. A spring tide can wash a child onto the shore of young adulthood. We see the navigation of Sophie’s memories (Frankie Corio) on the boats, beaches and buzzing nights in Turkey—steered by her adult self—as she tries to meet her dad below surface level. A film—in general, an artwork—becomes memorable when it makes the particular sensitivity of a general affect communal. In Aftersun, Wells seizes the uneasy innocence of a child with such specificity. Aftersun steps shakily onto that fragile platform of safety. Mostly every child has never forgotten their first feelings of capsize. At the seaside with my family when I was barely three years old. I am the first grandchild on my mother’s side. We play hide and seek. Through her, I inherited a sense of competitiveness. I hide until their voices die out and when I stand up later, no longer happy with this game, I find myself for the first time alone; mental terror of something feeling inexplicably lost.

January 14

To become fluid like the ocean and like the tide coming on strongly, but receding with ease, happy to retreat. Letting go. A drifting back and forth and back and forth and back. Waving the tailbone, but slowly, as if moved by some substance. To become expansive than ever, doing the slow dance, oceanic.

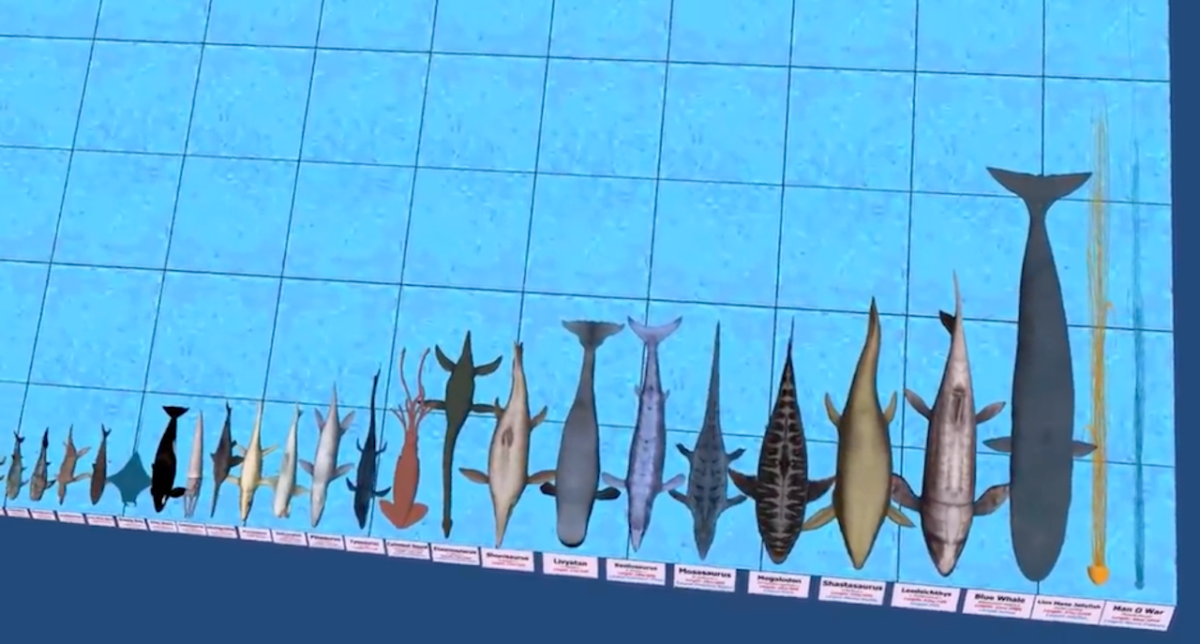

Back at Kong’s Finest Hour’s headquarters, we find Kluge writing about the medusa jellyfish, a creature speculated to once have been on the same evolutionary course as humans. “They possess cells that are presumably crossed with quantum pairs found in one of the early clusters of galaxies within the Coma Berenices constellation.” Unfortunately, the seas heated up and these medusas were banished to the depths and trenches of the ocean and cut off from the sunlight. “It is an often overlooked fact that the light of the sun is the second source of intelligence along with self-will (conatus), the fountain of life, which derives from the humming of cells.” They never became overlords, but the Portuguese Man-O-War is—it’s the largest animal known to history, second only to the lion mane jellyfish, at least until modern biology dredges up something even larger from the depths of the ocean.

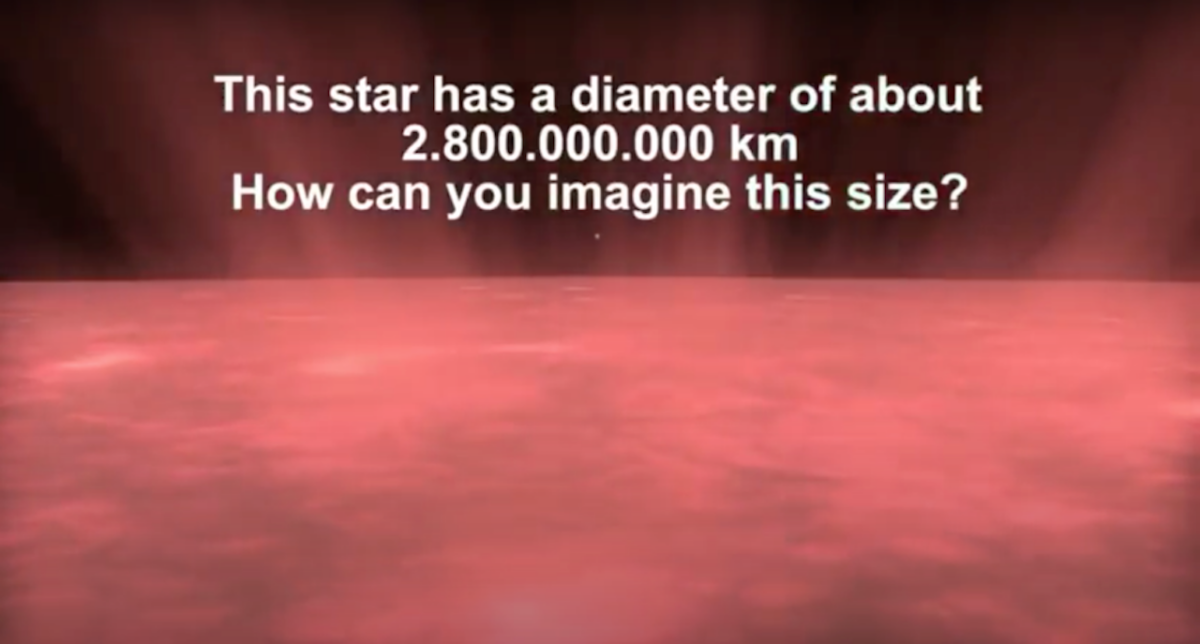

After extensive late night YouTube browsing, we could not decide about which we know less about: the space above or the waters on Earth. We eventually concluded that in each vast body there are points of reference, and these respond to each other if provoked. ‘Quantum Entanglement Theory’ is how it’s called in quantum mechanics, but in esoteric circles it is called a form of love. It is hard to imagine the size of love in any given situation. There is a difference between knowing what you don’t know and not knowing what you don’t know.

January 18

I see the word everywhere. London, city of undercover wells. THE WELL: traces of old taverns and overnight stays, like an alluring pilgrimage.

Well Worship: I found myself in the middle of the night deep into the lore of the London wells. A place densely populated, full of thirst, unable to be lessened by the filthy Thames. It is a place full of interest for the kind of ‘well hunters’ I was tracking down online, those who attempt to find the exact location of historical wells. Although it is certain that there are more than twenty holy wells or springs connected to London, most of these have been replaced by systems with the most recent technology or have altogether been destroyed or buried under the city’s building blocks. “Ancient water supplies do not survive well in urban areas”, states the article I am scrolling through.

January 24

The heron that flew down over the river just as I threw my bottle of vows.

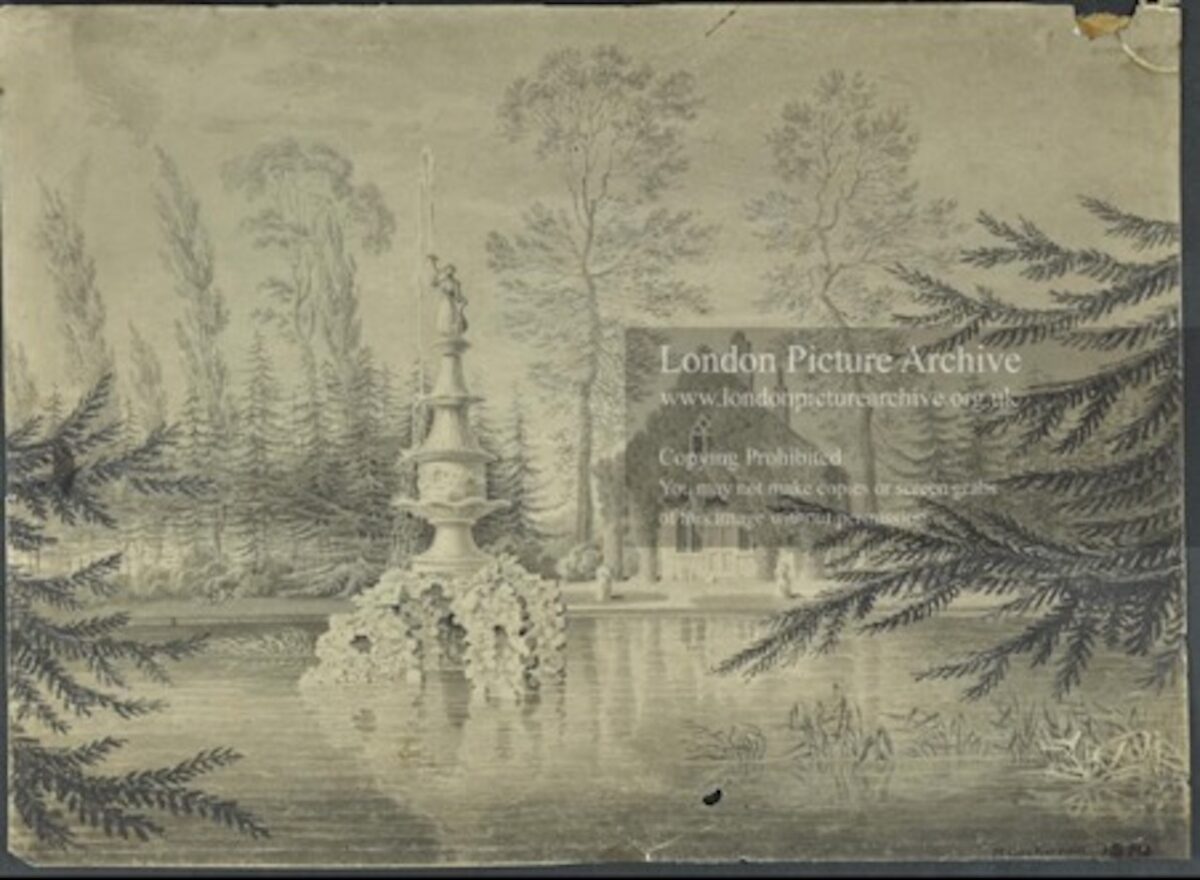

There are at least three explanations for the name of the London borough of Camberwell, of which I am more or less a resident. Some are more grounded in etymology than others. That the name stems from the presence of a well in the area is certain. Its location is verified, though at present it no longer exists. It is described as an unusually large well (tumulus), an inverted mound, and certainly a massive opus at the time of its insurrection. In the last stage of its long life, it served as part of a big, ornamental garden—adjacent to a place called Fountain Cottage—full of follies, and next to them this ancient water pit.

Being geographically the highest point south of the Thames, Camberwell is supposed to be one of the earlier places of settlement, originally used as an outlook point. In the Medieval Ages it was widely assumed London had been founded by Prince Brutus who had three sons and a kingdom to divide threefold some three thousand years ago. This means at that time, London had been attributed not to the Romans, but to the mysterious Trojans. One of Brutus’ sons, Camber, received the area that included London, and unlike the offspring of so many kings like Lear, he and his brothers accepted the presets and reigned over their realm harmoniously, the well being both a functional attribute and a tribute to Camber’s rule.

Another story goes that the well was a source of healing for the weak and wounded, water with medicinal properties. That certain waters possess these powers is supported by many ancient tales and beliefs on British grounds. It is no coincidence, then, that the original well stood just a stone’s throw away from Camberwell’s St. Giles Church, named after the patron saint of the crippled—the word ‘cam’ being related to a crooked work. Even The Hermit’s Cave, the old pub a bit further down the street I sometimes visit for a pint, is a nod to the lonely saint.

Reiterating: the word ‘cam’ being related to a crooked work, ‘Camber’ then means an arched piece of timber, simply referring to the strange shape of the big well. I fall into life and sink. Some histories don’t require me to venture into a past unknown, but make me choose from the garden of forking paths. Which of each plausible history is real? Did they occur all at once? Am I the audience to a densely cemented reality?

January 26

There is no end point at which all things will be hardened and laid out. We are meant to be twirling with the water again and again.

At a party someone recently told me with ardent conviction that no one knows how eels reproduce and that every single one of the species can be traced back to the Bermuda Triangle. Her eyes peered into mine with such assurance that I didn’t even bother verifying: the eel story remains one of uncertainty. In Aphotic Zone (2022), Emilija Skarnulyte descends four thousand metres deep into the indigo pacific waters off the coast of Costa Rica to a point of historical pressure: at that point the water, turns black, it turns into a screen for imagination and the Duga radar appears, sunken in the sandbank. Did you know, when fish float vertically, the tides affect them less, allowing for a point of rest? Whereas they glisten in the sun, the aphotic zone is also known as the dark ocean, where natural light no longer penetrates the waters. In the murky ocean floor, Garden eels bury their tail into the sand and spend their life being pulled softly by the tides, as if a colony of seagrass.

A point of perceived stillness. A missile system covered in water cubics. But sound travels faster through water than air, we would hear the sounds of destruction before being able to see them. Most of the sacred Irish wells are said to have guardians in animal form. One well in particular has as its guardian pair a couple of magic trout. I wonder about their defense mechanisms.

January 28

We are close to the beach actually. A wave could wash us away but wouldn’t dare because our whole plan has been arranged so nicely.

“In the water you see the one you love. It’s true. When I was little I saw lots of things. And last year, I saw you.” In light of a Lumière film programme Éric Rohmer interviews François Truffaut on his first time viewing Jean Vigo’s L’Atalante. It’s a simple story, rewritten from an existing screenplay, about a young married couple adjusting to a new life hitherto unknown to them. “It’s a film as a private journal,” says Truffaut. It’s the young woman twirling slowly like a jellyfish around the young man. It’s the murky water. ‘And the traveller dropped dead struck down by the picturesque’, Truffaut quotes Max Jacob. It’s the bubbles of glowing poetry coming out of the murky water. Their entanglement. And the traveller lives and wades onwards.

Bibliography

Alexander Kluge, Kong’s Finest Hour: A Chronicle of Connections

Colm Bairéad, The Quiet Girl

Silvan and Dalphin, Les bains de la jetée des Pâquis

Charlotte Wells, Aftersun

Reigarw Comparisons, Sea Monsters Size Comparison

morn1415, Star Size Comparison

James Bonwick, Well-Worship

David Furlong, London’s Holy Wells

pixyledpublications, Some little known ancient wells in the south east Greater London area of Kent

John Chaple, The ancient well of Camberwell

Emilija Skarnulyte, Aphotic Zone

Jean Vigo, L’Atalante

1968: Éric Rohmer and François Truffaut discuss Jean Vigo’s L’Atalante