Leos Carax’s Annette has been announced as his very first musical. After a career of poetic, romantic dramas—so the story goes—the French director discovered the narrative and filmic value of the music of Sparks, an American band he had admired since he was a teenager. About eight years ago, brothers Russel and Ron Mael presented a collection of 42 songs to the French director: the album was a script in itself, consisting of dialogues, monologues and sung descriptions of situations. Annette’s storyline was already there: Ann, a famous soprano at the pinnacle of her career, falls in love with Henry McHenry, the motorcycling bad boy of the Los Angeles comedy scene. He is provocative, jokes about the holocaust and the hypothetical murder of his new girlfriend. She is tender, compliant, and remains blind to Henry’s increasing manipulation. Nonetheless, as their first love song repeatedly states, they “love each other so much.”

Just as Annette is described as Carax’s first musical, it is also described as “the weirdest musical ever made.”Annette has repeatedly been described as weird, from “the weirdest movie of the year”, to “weird and wonderful”, to containing “all the wrong kinds of weird.” See e.g. Sims, David. ‘What a Weird Movie About a Puppet Reveals About the Nature of Evil’, The Atlantic, August 18, 2021. https://www.theatlantic.com/culture/archive/2021/08/leos-carax-annette-movie-review/619788/ Intentionally, he casts doubt on the basic constituents of his film: Where does the stage end and “real” life start? When are the actors playing—both the actors of the film (Marion Cotillard and Adam Driver) as well as the actors in the film (Ann and Henry)? Blurring the thin line between stage and life, actor and character, the musical becomes a multi-layered collection of self-conscious songs, actions and gestures. Even when Ann and Henry are not on stage, Cotillard and Driver are still on the film set. Even when the fictional couple does not perform, they are being performed. In this “weirdest musical ever made”, off stage and on stage are one.

However, when we consider Annette in relation to the director’s previous work the alleged weirdness does not seem so weird anymore. Over the course of twenty years, Carax has experimented with a wide range of musical elements, from simply staging a song, to emphasizing artificiality, to using language performatively. Since his first feature, 1984’s Boy Meets Girl, he has been exploring the interferences between cinema, theatre and musical. Although Annette might come across as his first full-blooded musical—if only because up to 90 percent of the lines is sung, as in Meet Me in St. Louis (Minnelli, 1944) or Les Parapluies de Cherbourg (Demy, 1964)—it is merely an accumulation of his long-lasting interest in theatricality and musicality. The musicality that, so far, had been repressed is now fully expressed.

Arguing that Carax has made musicals since he started directing films, involves, at the same time, arguing for a redefinition of the term “musical”. If we compare his repressed musicals to the genre’s conventional prototype—viz. the Hollywood musical from the 1940s and 50s—his whole oeuvre is excluded from the genre, just like the majority of musicals produced after this brief period. Adrian Martin has rightly suggested that musical-ness does not depend on the degree of conformity to the “Broadway-defined model of musicals”, but exists in a plurality of forms and is scattered throughout a large part of modernist cinema.Martin, Adrian. ‘Musical Mutations: Before, Beyond and Against Hollywood.’ In Movie Mutations: The Chaning Face of World Cinephilia, eds. Jonathan Rosenbaum and Adrian Martin, 94-108. London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2013. A musical is, thus, not a wholistic unity—a comforting yet exclusive illusion—but a fragmentation of songs as well as words that sound like songs, and dance moves as well as movements that look like dance. Within this scattered universe, Carax’s films embody musicality.

The Music: Floating Somewhere in Between

The acknowledgment that music is capable of more than merely setting the tone is probably one of the greatest achievements of the musical genre as such: it is capable and even successful in supporting and conveying a story. In Annette, as in the majority of musicals, the story is fully intertwined with the music. While the main plot elements give rise to the singing of a particular song, they only exist because they are carried out by these songs. When, for example, Ann and Henry go for a walk in a sunny forest on one of their first dates, they burst into a love ballad. Later on, when Henry realizes that this love ballad was actually written to Ann by her piano accompanist, who she dated before going out with him, he ends up in a vivid discussion with his love rival—again all while singing. In both situations, the song is sparked by the development of the narrative. Conversely, these plot elements depend on their musical translation for their comprehensibility and even for their existence. Like most of their work, the collection of songs Sparks presented to Carax is narrative in nature. Their music tells a story, consists of dialogues, monologues and descriptions. It is a self-containing source of narrativity through musicality.

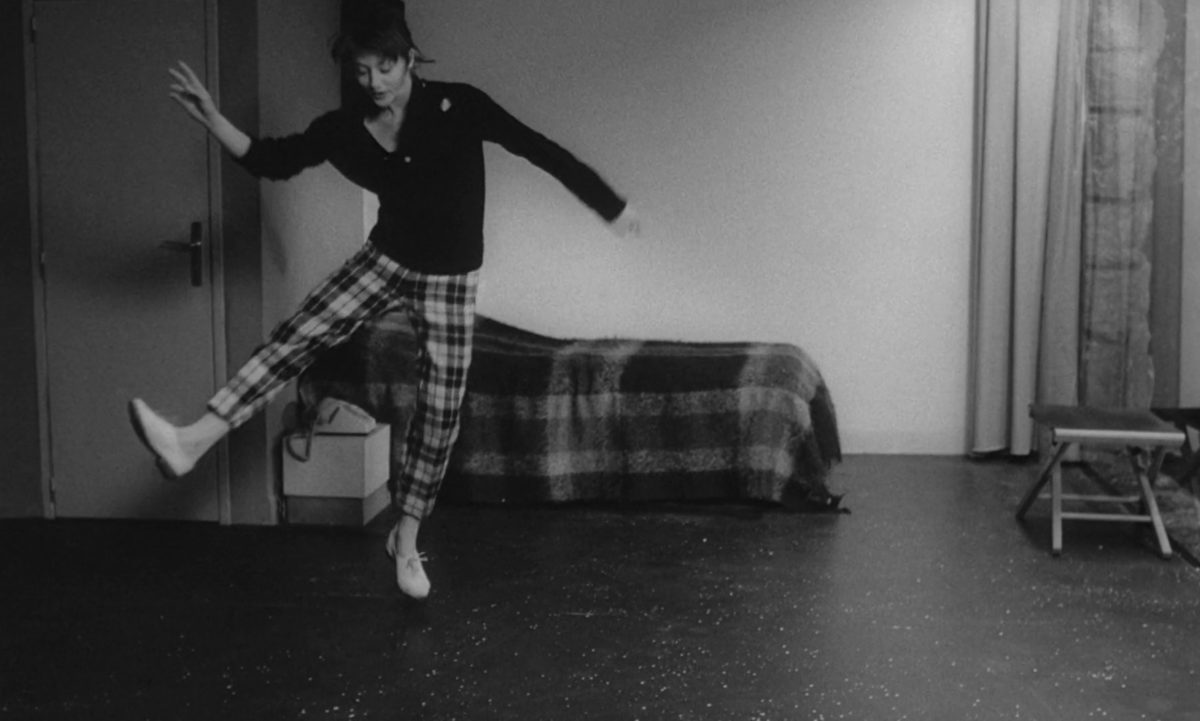

Although no one bursts into song, this reciprocity between narrative and music is already announced in Carax’s first films. In his debut Boy Meets Girl, the nameless boy, played by Denis Lavant, wanders through the streets of Paris listening to music on his headphones. As soon as David Bowie starts singing that he will live his dream, the boy’s perspective on the bleak city surrounding him changes. When he walks past a couple of lovebirds, they start kissing passionately and even cinematically, like Carry Grant and Ingrid Bergman in Hitchcock’s Notorious (1946). As if on a rotating platform, they spin around their own axis, secretly glancing at the camera. What the boy sees while listening to the music takes on a theatrical form: the city performs for him, just for him. Cross-cutting this theatrical walk with shots of the girl tapdancing in her bedroom, Carax creates confusion on the origin of Bowie’s song: is it the song the boy is listening to or the one the girl is dancing to? Is the song intradiegetic to the walking scene and extradiegetic to the dancing scene, or vice versa? Or does nobody hear the song, because it remains fully extradiegetic?

The confusion of the intra and extradiegetic realm is characteristic of the musical’s basic structure. Every time a group of actors bursts into singing, accompanied by an instrumental score without visual, localizable source an implicit conflict arises. On the one hand, the music belongs to the narrative reality because the actors contribute to it and interact with it—hence, the music is intradiegetic—but, on the other hand, it transcends this reality because not one of the actors is fully aware of the whole in which they participate—hence, the music is extradiegetic. Musical theorist Rick Altman named this very common phenomena “transcendent supra-diegetic music”, as opposed to the common term “extra-diegetic music”, in order to emphasize the paradoxical simultaneity at work: the diegetic sounds and voices are replaced by a transcending layer of music to which every individual actor participates without possibly knowing the whole which he helps to construct.Altman, Rick. ‘The Style of the American Film Musical.’ In The American Film Musical, 69-70. Indiana: Indiana University Press, 1988. The musical is, by far, the only genre that succeeds in depicting both realms at the same time, dismantling the paradoxical character of this simultaneity.

The appearance of transcendent supra-diegetic music, one of the basic constituents of the musical as genre, is not only the primary characteristic of Annette—a film many would consider a musical—since indeed the boundary between the intra and extradiegetic is confused, simply because the characters participate in the songs, unaware of the whole to which they contribute. This is characteristic of Boy Meets Girl as well. Both characters seem to react to the music we hear—the boy by changing his perspective on external reality; the girl by tapdancing—but in reality only one of them is truly hearing the music. Hence, the music which is intradiegetic for one of them, is extradiegetic for the other, and, furthermore, neither of them is fully aware of the whole in which they participate. Likewise, in Les Amants du Pont-Neuf (1991), the homeless Michèle (Juliette Binoche) starts running through the hallways of a Parisian underground metro station as soon as we hear a suspenseful melody played by an undetectable cello. It is only after several minutes that we see a musician playing in one of the station’s corners. What we had considered to be an external soundtrack intensifying the sequence’s tension, appears to be an internal performance. Again, the music with which the protagonist seems to interact transcends the conventional dichotomy of the intra and extradiegetic. Although these characters do not perform a Busby Berkeley group choreography while singing a polyphonic sing-along, the final product is profoundly musical.

The Stage: Everywhere, Ever-Fading

This playful yet meaningful introduction of music in the narrative development raises a question that has concerned artists since Shakespeare: “Where is the stage? Is it outside or is it within?” Towards the end of Annette’s first song, Cotillard and Driver sing this question, frontally addressing the spectator. This first song serves as an introduction to the actual story, as a transition from the extra to the intracinematic. Following Carax’s countdown, Sparks start singing one of their songs in a recording studio. After a few lines, they leave the studio and move into the city, where the film’s actors join them one by one like a walking flash mob, continuously repeating one question: “So may we start, may we start, may we, may we now start?” Towards the end of this first song, Cotillard and Driver put on their characters’ clothes, enter their role by metaphorically crossing the street and take off for the shows they have to perform that night.

Already from the film’s very first words, from its first song, Carax emphasizes the characters’ threefold statute: Cotillard and Driver perform the part of Ann and Henry, who, in turn, perform a variety of roles by profession. The protagonists’ identity is not flat, nor round, but fully proliferated and fragmented. Carax creates a constant interference between these three stages of being. On a first level, Ann and Henry seem to be conscious of and concerned with their fictional nature: in response to the prevailing artificiality—Annette features, among other trickery, a wooden baby and an overtly computer-generated raging sea—they desperately seek to confirm their own existence through language. On a second level, the explicit interference between the artists’ performances on and off the intradiegetic stage further complicates their identity. During one of his shows, Henry jokes about how he killed his wife tickling her feet. Not only is this a flashback to an earlier scene in which Henry actually tickles her, it is, more importantly, a prefiguration of the moment Henry forces her to waltz with him on the slippery deck of their yacht, causing her to “accidentally” fall overboard. Her death—or Henry’s act of murder—is also announced by Ann’s operas. She constantly performs tragic characters who die in the end, not knowing that her staged performance will soon become reality.

This fading between actor and character creates a persistent uncertainty about what is real and what is staged. When are Ann and Henry performing? Are they most real when on the stage—their natural habitat—or does the off stage space serve as yet another on stage space? Even when Ann and Henry are not performing, when they are off stage, they are still being performed by actors on a film set—a peculiarity that Carax unceasingly emphasizes. In Les Amants du Pont-Neuf, the impossibility of distinguishing life from performance, playing from being, takes on a more embedded role. At the start of the year-long renovations of the Parisian Pont-Neuf, the homeless Alex (again Lavant) refuses to leave the public bridge that has become his private home. When he finds a sleeping, partly-blind woman on one of the benches of the empty bridge, a fairy tale romance begins—the story of “les amants du Pont-Neuf”. Not only is the bridge a rough reality where warm-hearted people excluded from any privileges brave the cold of the night. It is, all the more, a place of spectacle, fantasy and performance. The line between these two realms is constantly fading, since, beautifully contradictory, the real itself—the physical presence of the cobblestone bridge—serves as a source of escapism for the characters from their own tough reality.

The Pont-Neuf is a locus of performance: it is the stage on which Alex and Michèle can be who they want to be. This theme of pretending, desiring or even being somebody else runs through Carax’s oeuvre: the nameless boy in Boy Meets Girl dreams of being a famous film director; the protagonist of Holy Motors (2012) performs the lives of others for a living; and Alex, in Mauvais Sang (1986), practices the art of ventriloquism. Similarly, Michèle has escaped her past—a wealthy past in which she lived in a suburban villa, worked as a professional painter and passionately loved her cello playing husband—and takes on the role of a vagrant once she is on the bridge, on the city’s stage. Like in Holy Motors, it is not so much a question of playing a different part, but of living it. The couple’s escapist desire to stage and romanticize their own lives climaxes in the famous fireworks sequence. During the celebration of the bicentennial of the French Revolution, Alex and Michèle dance wildly and intensely on their bridge. Against a skyline of colourful fireworks, they jump, waltz, climb and roll, completely absorbed in the fast-fleeting moment. Once again, floating somewhere between the intradiegetic radio and the extradiegetic soundtrack, the music quickly changes from waltz to march to hip-hop, and so on. Michèle an Alex dance like beautifully crazy lovers. On their stage made of cobblestones, they perform for themselves, for each other, for the city and for us, the film’s spectators.

In this ever-fading universe where reality and performance blend, the only stable principle is the spectator’s subjectivity—a principle that is, however, unstable in itself. As one of Holy Motor’s characters contends, quoting a famous line by the 19th century novelist Margaret Wolfe Hungerford: “beauty is in the eye of the beholder.” Hence, Carax’s fascination with self-conscious make-belief is not simply a visualization of Shakespeare’s “all the men and women merely players”, of the idea that every person fulfils a certain role, be it imposed by God, an objectifying other or a self-directing self. Nor is it an artistic demonstration of how each person is a different version of herself in a different situation. Like Les Amants du Pont-Neuf, Annette is not a film about something—about performance, self-consciousness, theatricality or authenticity—but a phenomenological experience that creates beauty to be discovered by “the eye of the beholder.”

The Performance: Acknowledging Reality’s Realness

Since they are continuously confronted with their own status as actors and the impossibility to distinguish stage from reality—a confrontation that, so it seems, lies in their own hands—Henry and Ann feel the urge to convince themselves of their own realness. Explicitly creating their own willing suspension of disbelief, they persuade themselves that they are indeed the role they play. Sparks’ songs play a crucial role in this never-ending attempt of convincing or, put differently, misleading. Generally speaking, the songs in Annette serve three purposes.

First of all, the singing functions as the musical equivalent of mere spoken words. Dialogues and monologues are sung as in some of the major examples of the history of the musical. In Demy’s Les Parapluies de Cherbourg and Une chambre en ville (1982) all lines are sung, but this approach is more of an exception than a rule. A more common approach can be found in, for example, Singin’ in the Rain (Gene Kelly and Stanley Donen, 1952) and Guys and Dolls (Joseph L. Mankiewicz, 1955) where only a selection of dialogues is translated into songs. The second purpose of Annette’s music is, however, more inventive and unique: the often ominous songs performed by an off-screen women’s choir serve as a modern adaptation of the Greek tragedy’s choir. These anonymous outsiders share their perspective on the events and make cautionary predictions. When it turns out that Henry is not the funny, easy-going comedian he pretends to be, but a manipulative husband who might or might not have abused his previous girlfriends—these women’s testimonies appear only in Ann’s nightmare—the choir repeatedly asks: “Something’s about to change, is it something we should fear?” Like in the ancient Greek tragedies of Aeschylus or Sophocles, they express the concerns, questions and criticisms of “the people” in general, and the present spectators in particular.

At first glance, the songs’ third function might come across as a rather awkward and redundant use of music. When Henry, for example, holds the new-born Annette—represented by a wooden marionette-like doll—in his arms for the first time, he melodiously proclaims that “this is a baby”. When he takes a walk with Ann on one of their first dates, they cannot stop declaring that they “love each other so much”. These repeated descriptions create moments of calm and contemplation in a dynamical film that barely offers time to breathe—ironically, in the introductory sequence described earlier, Carax himself asks the spectators to hold their breath until the end of the film. But this is not the main function of the descriptive phrases: they, first and foremost, serve to convince the self-conscious characters that the reality they perform is indeed the only true reality. They are, thus, performative in nature.

(Re)introducing the term “performativity” with his 1962 book How to Do Things with Words?, the British philosopher John L. Austin sparked a small revolution in cultural studies.Austin, John E. How to Do Things with Words?. Harvard: Harvard University Press, 1975. Utterances such as “I now pronounce you wife and husband” do not only express the speaker’s intention, but, through the act of the expression, change reality itself. The action described in the utterance—in this case, the pronouncing—is performed by the utterance itself: hence, it is performative. In this regard, the descriptive sentences in Annette are not merely descriptive but performative, since they change reality the moment they are uttered. When Henry sings “this is a baby” he changes the status of the wooden doll, simply by pronouncing the words. Tautologically stated: declaring that the doll is a baby, makes him (and the spectator?) believe that the doll is a baby indeed. Likewise, when the couple declares their love to each other in endless repetition, they are explicitly constructing the intradiegetic reality—their own willing suspension of disbelief—while singing. In Annette, the music’s performativity is always a form of make-belief.

Although Annette is Carax’s first fully sung musical, this play with performativity has fascinated him from the start of his career. In Holy Motors, the acts of the nameless—and contentless—protagonist contain the same performative structure. Like a businessman, Denis Lavant’s character is brought from one appointment to another in a luxurious white limousine. On each of these appointments, the protagonist incarnates a different role: a warm-hearted housefather, an accordion player, a grandfather on his death bed, the satyr-like Monsieur Merde from Carax’s Pola X (1999), a motion-capture actor and so on. Carax does not reveal who the protagonist is when he is outside of these roles, since he only exists as them. His performances are, therefore, not a form of playing but a form of being: each time, he actually is the role he plays. Whereas, in Annette, the realness of the often-unbelievable reality is acknowledged by the descriptive, sung lines, it is, here, acknowledged by the act of performing. Holy Motors does not only consist of performative utterances, but of performative acts as well—that is: acts that change reality while being acted out. With each blink of the eye, each gesture of the hand, each sound of the tongue, the protagonist constructs the reality he is to live. Through the act of acting, he gradually convinces himself, and the spectator with him, of the realness of the particular reality he performs. He is no more or no less than who is at that moment.

This recurrent use of performativity is, however, only one emanation of the repressed musicals Carax has been making since the beginning of his career. A profound sense of musicality has been unfolding and refolding itself with each new intertwining of narrative and music, each new metaphorical stage, each new self-reflecting actor and each new performative line. Whether Annette is indeed “the weirdest musical ever made” remains, in the end, a question of personal taste. Whether it is his very first musical is, however, a self-fulfilling question based on false premises. Annette is not Carax’s first but his latest musical.