In the moments before you die, time slows to the point where you can think over all your memories, or so I’ve heard. I’ve also heard that the world is moments from dying—by heat or by disease. But we all still live twenty-four hours a day, even if the Earth is starting to spin slow.

Film projectors have spun twenty-four frames per second since at least the late 1920s. The steady whir has laid a backbeat for these fast hundred years: world war, space travel, global famine—but also the laid-back days between, a stroll through a small town. Sometimes twenty-four frames isn’t enough to capture what goes on in a second; sometimes it seems far too many.

Film critic Cristina Álvarez López summed up the divide between measures of time in a tweet: “human time IS NOT universal time.” She was writing about a scene in Rebel Without a Cause (Nicholas Ray, 1955), in which bored high schoolers watch an explosive light show depicting the end of the Earth. Sparks bursting from the screen are intercut with shots of yawns and legs kicked up on chairs. How can the teenagers understand the end of the world, when they can only see forward to the party next Friday; and how can the world understand the teenagers, when all human life is a blink in its history? The scene understates the catastrophe—each spark would be another region on the globe storing up energy and exploding—while recording the kids under a microscope—we see the gleam in a boy’s eye trying to flirt and the creases in a flannel shirt shifting as another readjusts himself. After the light show, the projector powers down, leaving an alien metal structure that seems distant from both the stars above and the humans below. We spend our lives in meticulous detail, while the universe walks in large steps, leaving footprints too spread out to interpret. The movie camera provides a counterpoint to both, an objective measure by which to chart the gargantuan and the mundane.

Maureen Fazendeiro and Miguel Gomes’s The Tsugua Diaries (Diários de Otsoga, 2021) was shot during a period of global panic—the height of the COVID-19 pandemic—but concerns itself with the lives of three people on a small ranch. Crista, Carloto, and João build a greenhouse for butterflies over the 22 days in which the movie takes place, though such a goal is hard to pick out among the hot tub breaks and meta-filmic discussions—the crew plays active roles in front of the camera, discussing plot points and set logistics—not to mention the fascination for visual texture over intelligibility. An early shot of Crista watering plants inside the greenhouse refrains from any shots of the structure, instead following her face closely as she moves, observing the shifting plant tendrils in the foreground, mesh netting in the background, and lens flare pouring in from above. Detail trumps structure.

The movie opens on its three actors dancing in the house on the ranch, spaced equally across the frame, each standing in front of a separate window frame. The bass line from Frankie Valli’s ‘The Night’ pumps, though it doesn’t reverberate naturally around the room. It’s clear that it was added in post-production; the moment recorded on set is already made separate from the moment spent watching it. Still, they dance precisely to its rhythms. Carloto breaks rank and the camera follows, then cuts close to isolate him, framed starkly in front of a bright window. Though Carloto stays continuous over the space of that cut—he starts a motion in the wide shot and ends it in the close-up—the world off-screen obeys separate rules: we find out moments later that João and Crista are outside, kissing passionately. There was no break in the song to imply the passing of time, nor did Carloto seem to notice his companions have left until he turns to look for them. Like in Rebel Without a Cause, something in one shot moves along a different timescale than something in another; the beat of ‘The Night’, representative of the movie’s steady pulse, provides an outside view on both.

The largest obstacle to narrative intelligibility, however, is the overall structure of the movie. Title cards mark each of the 22 days, but they move in reverse: first we see day 22, then move backwards one day at a time until reaching day 1. This foregrounds the gradual changes that take place, as even normal markers of time become strange when viewed in reverse. A quince slowly rotting—or slowly un-rotting, as it were—becomes a synecdoche for other processes on set: the accumulation of film recorded, the loosening of mask protocols, or co-director Fazendeiro’s pregnancy. The movie first portrays her as a voice over a walkie-talkie, then lying prostrate on couches in the days before labor, and then finally on her feet. By ordering them backwards, these signs of a difficult pregnancy do not seem a peculiar hardship for Fazendeiro, but rather a fate to be expected. In the late scenes, she is “expecting”, but the movie has already shown the result—she and Gomes’s baby Helena, to whom the film is dedicated. The images throughout seem to anticipate what will arrive in the future: a quince will rot, a dog will run away from home.

COVID’s ceaseless global spread, and threat of spread within the Tsugua cloister, becomes palpable through the film’s backwards ordering. Naming the days sequentially, as opposed to using the exact, recalls the early moments of pandemic, when we thought we might be able to count away the days until it would all go away. Conflicts evaporate as the numbers decrease, and thousands more people around the world are brought to life in the jump from one day to the previous.

On day 13, a fight erupts around a picnic table between Carloto and the rest of the cast and crew. He had gone surfing on his day off, so he now carries the possibility of infection with him. The camera pans to follow him walking behind everybody else, and lands in a private clearing, framed and isolated by a tree trunk. Harsh winds blow against him in conjunction with the screams from off-screen, Carloto’s mistake rendered as inevitable as the weather. The composition has a ghostly connection with the similar one from the first scene, of Carloto in front of the window—and Carla’s choice to kiss João instead of Carloto is a direct result of this moment by the tree trunk. The party haunts the fight, since the movie shows it first, and the fight haunts the party, since the fight happened first. The scene proceeds via close-ups and two-shots, betraying the limited, human scale on which it takes place: its players have no knowledge of Carloto’s health, and no knowledge of the thousands of people infected outside the walls, to whom Carloto’s sickness would be the smallest drop.

The haunting extends after the cut to day 12, in which the eerily empty house—it’s everybody’s day off—waits to be filled by some mistake. If it hadn’t been Carloto surfing it would have been something else; one day will kick up dirt to lay on the next. In an image, there are the ghosts of the cruelties that have formed it, and the ghosts of the cruelties that it will form: The Tsugua Diaries posits these relationships as universal law rather than just happenstance.

There is a long history of movies that juxtapose measurements of time: the human time of daily tasks and the universal time of the world’s problems accruing, and the movie time, its give-or-take two hours that stands outside both. Often they take place, like The Tsugua Diaries, removed from the context of normal life—on vacation, far from home and work, where each minute can alternate between languor and excitement. Elements of The Tsugua Diaries can be traced through all of them. To take a few examples: Le Rayon vert (Éric Rohmer, 1986) posits the single moment of sunset as the cure for its heroine’s years of confusion. Du côté d’Orouët (Jacques Rozier, 1973) charts the falling-out of three friends as they trade romantic partners over a summer; Carloto’s mournful look at João and Carla kissing recalls the hatred that grows between these once-inseparable friends. Once Upon a Honeymoon (Leo McCarey, 1942) sets the micro-timings of comedy and flirtation against the larger-than-life tragedy of World War II; the movie indulges the fantasy of a European vacation during the war as Tsugua indulges partying with friends during COVID quarantine. George Kuchar in Weather Diary 1 (1986) similarly hides out from a disaster; his first-person video diary from an Oklahoma motel during a tornado concerns itself with the mundanity of salad dressing and Godzilla on TV. And closest of all, One Way Passage (Tay Garnett, 1932) makes time stretch and contract aboard its month-long ocean liner journey; it’s a doomed fling between a death row inmate and a terminally-ill patient, confronting the end of life much like The Tsugua Diaries confronts the end of the world—in a collection of small, joyous, discontinuous moments.

These particular movies share with The Tsugua Diaries the peculiarity of marking time passing with interstitial title cards. Much as the way intertitles in silent films translate images into narrative, these temporal titles place isolated scenes across a grand timeline, turning a ninety-minute movie into an entire summer. They reinforce the constructed nature of the fiction: many days can pass between filming one shot and the next, and putting a time card in between makes that gap explicit. Le Rayon vert’s handwritten titles acknowledge the protagonist’s subjective recognition of the summer passing, while Du côté d’Orouët’s geometric designs mirror the steadily changing network of relationships between the five characters. Time passes on a human level. The cursive written by Marie Rivière betrays her years of schooling, and evokes the studied carelessness by which she lives—evidence of history and personality even without her on screen. The image jitters slightly as film passes through the projector, words and background moving together. Once Upon a Honeymoon and Weather Diary 1 both use news events as anchors: the former a clock with a swastika for hands atop a map of Hitler’s conquests, and the latter Weather Channel footage playing in Kuchar’s motel room. Time passes on a universal level, outside the characters’ direct experience. The elements making up each of these images move out-of-sync with each other: the swastika shakes at a different rate from the map, and the CRT television gets caught halfway between two images. These self-conscious special effects break the realism of the movies—even more so than the imposition of a title card to begin with—and as such serve to index each constituent piece in its own separate moment of recording. Kuchar is recording a recording, and each link in the analog chain adds its own marks. In the end, the effect is humor—bolstered by Honeymoon’s over-the-top “A. Hitler” calendar for conquest and Kuchar’s growing obsession with local weatherman Gary England—because the gulf between watching a movie for a few hours and contemplating such a grand scale is too great to do anything but laugh.

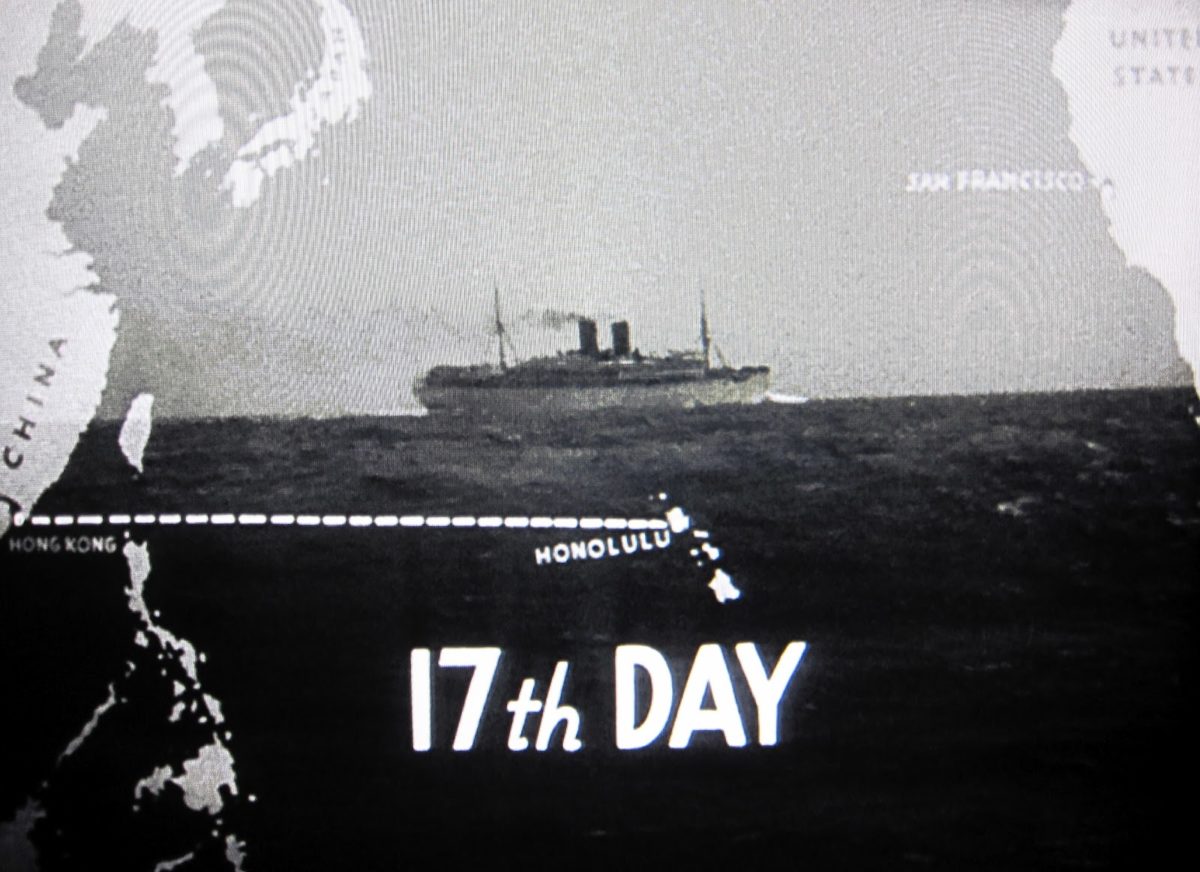

In the first minutes of One Way Passage, William Powell and Kay Francis smash cocktail glasses and leave behind the criss-crossed stems. “Known him long?” Francis’s friend asks. “Ever so long”, she replies, staring lost in the space where he just stood. “Where?” A pause, and Francis stutters: “I—I can’t quite remember.” They met by chance just a moment ago, but it’s as if Francis has seen the rest of the movie already, perhaps years ago so it’s foggy in her memory. Soon, title cards appear to mark the days of the trip, and to remind of the forward, linear progression of time that Francis had just threatened to thwart. These titles take the form of a map of the journey from Hong Kong to San Francisco, a dotted line serving as a visual heuristic for the hourglass of the lovers’ lives, along with a label of the days since departure, superimposed onto footage of the ocean liner, which crossfades into the upcoming scene onboard. The fade contains a bit of the realism of Le Rayon vert’s handwriting and the map calls forward to the geometry in Du côté d’Orouët’s date markers, but most of all they carry the same bold irrelevance as the swastika clock of Once Upon a Honeymoon or the television broadcasts of Weather Diary 1. Sure, our heroes inch closer to death with each title card, but their romance moves on its own timetable. The lovers live more in their one-day tryst in Honolulu—and have more screen-time—than in the three days elided afterwards. Each scene flows with a curious continuity from the last, such that the cold pragmatism of the title cards seems to have lost its grip on the reality of the budding romance, rather than the other way around. One Way Passage inverts the standard melodrama tropes, of a glimpse at freedom serving to entrench the cruelties of normal life (see The Reckless Moment, Written on the Wind), or of the self-conscious transgression of societal norms (see All That Heaven Allows, On Dangerous Ground); it merely acknowledges that society’s standard measurements, represented in part by the title cards, cease to matter in the last moments of life.

The Tsugua Diaries draws a similar dichotomy in the space of its titles. Though they match the pastel shades of Du côté d’Orouët, the days’ letters are rendered in a static, digital typeface atop the dynamic, grainy, scanned-16mm backdrop. Blemishes and dust jump onscreen for one twenty-fourth of a second at a time, indexing the moment of filming while the text sits separate, an alien string of zeros and ones. Du côté d’Orouët also employs machine-made text, but its precise letters were eventually imprinted onto the same filmstrip as the background. As the film wiggles through its reels, text and background shake in-sync, a unified measure of time. In The Tsugua Diaries, the film runs through the scanner: time marked tangibly, visibly. The digital file, meanwhile, measures time by an electric current passing through a circuit board: invisibly, understood by diagram.

The digital atop the analog acts as a synecdoche for the creation of the movie as a whole. Discrete scenes were recorded onto film, then digitized and rearranged into their reversed order. The scenes play out like the blemishes flashing by on the title cards, accidental grace notes caught by the camera. The structured and the digital impose on that persistent imperfection, but the humans on camera don’t seem to mind. The universal passage of time is to them an afterthought, a cosmic joke best left ignored, when compared with the search for a lost dog or the arrangement of furniture in a greenhouse. Time hasn’t reversed; it’s twisted and deformed and become distinctly human. The Tsugua Diaries teaches no political lessons, though it directly addresses a world in sore need of them. COVID has tacked itself onto the long list of fatal concerns the world must carry: it will continue to haunt our images and our empty rooms. The Tsugua Diaries demonstrates an apathy beyond apathy—not a dance party at the end of the world, but a dance party instead of the end of the world.