“Some revolution this is!” snarls the protagonist in Živojin “Žika” Pavlović’s The Ambush (1969) as the young communist, thoroughly disillusioned by the film’s events, faces down the barrel of a gun. Those final lines may as well be a direct attack on the very concept of socialist Yugoslavia, forged out of revolution and battle in the wake of WWII. The film was promptly bunkered—a common enough practice in Yugoslavia for politically difficult work, meaning it was never banned, but rather just conveniently made unavailable for public consumption. You might assume Pavlović would hold back a little in his follow-up Red Wheat (1970), which he decamped to Slovenia to make. But instead Pavlović doubles down, pushing the viewer further face down in the mud to wrestle with the moral and historical implications of his storytelling. The two provide a diptych of anger and misery, fighting against official history, a story of chaos and mayhem. Pavlović was notoriously uncompromising as an artist, and yet there are subtle differences in Red Wheat that suggest an artist adapting to the challenges his work is facing: the tiniest shift going from presenting a collective view of cause and effect to an individualised view of it.

The Serbian-born filmmaker, the crown prince of a particularly Yugoslav kind of nihilism, spent much of his life fighting against one authority or another. An anthology film he directed alongside Marka Babac and Vojislav ‘Kokan’ Rakonjac in 1963, City, remains the only Yugoslav film to have been ‘officially’ banned during the socialist era (although officially is doing much of the heavy lifting). His early feature films—The Enemy (1965), The Rats Woke Up (1967), When I’m Dead and Pale (1967): all great heavy metal album titles too—depicted the existential crisis of the New Socialist Man, and the inability of wider Yugoslav socialism to build the utopia that it aimed to project out into the world.

Thereafter, The Ambush (1969) and Red Wheat (1970) went back in time to the immediate aftermath of WWII, and the chaotic rebuilding effort that was critical to the country’s later economic and cultural success, depicting instead how that rebirth included plentiful violence, terror, and oppression, filtered through Pavlović’s particularly nihilistic and dark vision of recent history. Communist Yugoslavia, like any state regardless of ideology, had its foundational myth: having emerged victorious in WWII and liberated itself from Nazi occupation, this was a multi-ethnic, multi-lingual state bought under a socialist structure that spoke of ‘Brotherhood and Unity’ and peace between peoples. Critiquing or attacking that foundational myth was akin to opening Pandora’s Box.

Take a Good Long Look: On Style

The Ambush and Red Wheat strike at the core mythos underpinning the state itself; two films about Communist apparatchiks bringing the good news about socialism to rural villages, quickly becoming disillusioned. The former has a young man losing faith when he sees the corruption and brutality of local Partisans; the latter arrives with the task of collectivising agriculture: initially polite, his inability to affect change sees him turn to exploitation, coercion and cruelty. These films are about the revolution in Yugoslavia, more specifically about the vast gulf between its state-sanctioned version and the reality, which saw people left behind within the sheer speed of change.

Their power lies in their naturalistic, direct filming style, built around deep focus long takes, honing Pavlović’s line of attack into a dagger. In The Ambush, each scene is stark and direct in its purpose. Aside from the deep focus long takes, Pavlović carefully composes spatial action across depth and width, a style not wholly dissimilar from the work of Miklós Jancsó in Hungary. The camera rarely dollies or tracks but almost exclusively zooms or pans gradually from a single point within the action—like a faraway visitor patiently watching the action from a static point.

Frequently, Pavlović uses this deep focus technique to contrast events across foreground and background. By 1969—five features in—he had trimmed this method down to its basics, a style he adopted in response to practical challenges which arose during the filming of The Return (1966). Prior to this—particularly his segment in City and The Enemy—his work showcased an interest in psychogeography, parleyed via expressionistic framing and noir-ish shadowing.

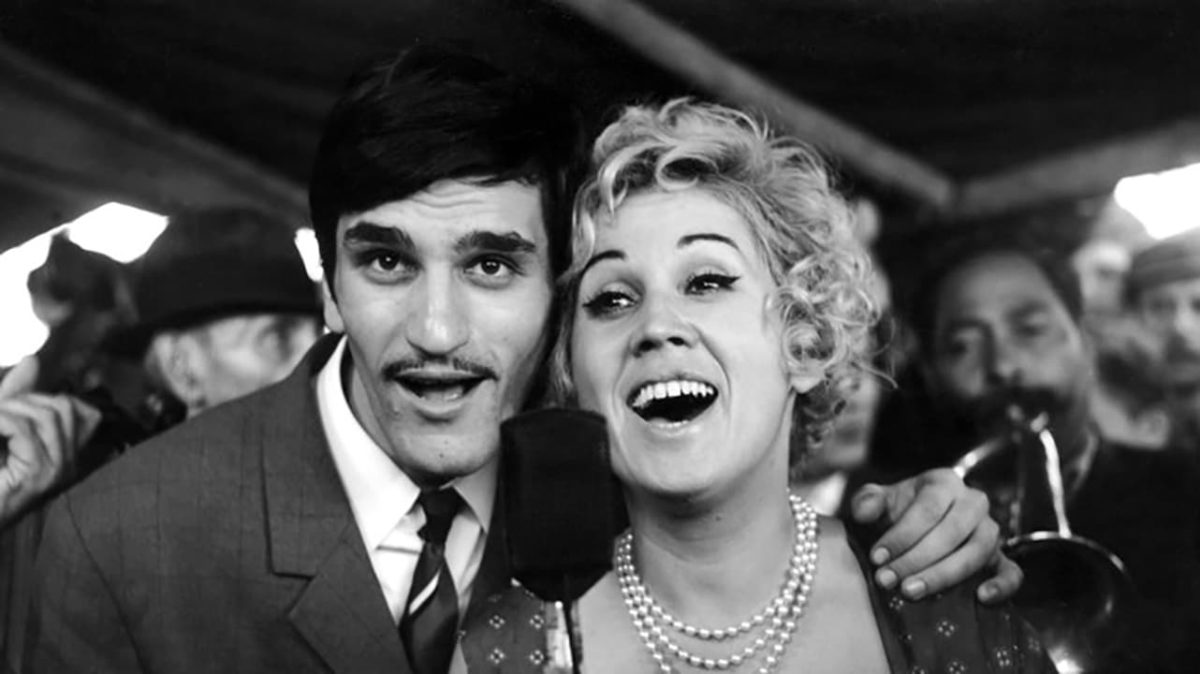

The Ambush represents the antithesis of that, directed instead towards a steely-eyed naturalism. One scene has the protagonist Ivo (Ivica Vidović) and his girlfriend (Milena Dravić) deep in conversation, oblivious until late what the audience can see early—a man is being beaten up in the background. A spectacular shot in the middle of the film has Zeka (Severin Bijelić)—a grizzled and cynical Partisan veteran—introducing Ivo to the local brothel (which is little more than a run-down farmhouse occupied by two sisters), before a Chetnik raid interrupts coitus (Chetniks were Serbian monarchists and ultra-nationalists who fought both the Nazis and the Partisans, but ended the war as little more than bandits). The duo, still pulling up their pants, run outside onto a small mound, hiding from the attack whilst the camera pans around and captures the raid in its entirety. It’s like something straight out of a western, itself a genre predicated entirely on constructing the foundational myth of the USA. In both scenes, the characters are preoccupied with something personal or banal, ignorant until too late of the barbarism about to infringe on their world.

For the protagonists of The Ambush, the story happens to them—they are devoid of narrative agency, history happening too rapidly to respond logically or rationally. If we take the film to be an attempt to wrestle with socialist Yugoslavia’s chaotic early days, and the unanswered legacy of violence and oppression that came with it, then this distant, multi-planed shooting style arrives as the most direct form of grappling with that history, devoid of expressionistic interference in favour of matter-of-fact storytelling.

Patchwork Chaos: On the Yugoslav Film Industry

The Ambush, produced in Serbia, was met with consternation and anger by Yugoslav authorities. Thankfully, the peculiar structure of the Yugoslav film industry meant Pavlović was able to simply move and continue working. Each constituent republic of the country (Slovenia, Croatia, Bosnia, Serbia, Macedonia, and Montenegro, joined later by the autonomous provinces of Vojvodina and Kosovo) had its own film infrastructure. Thus, we are not talking about one film industry, but more like a multinational patchwork of smaller film industries, in which directors, actors and crew could move around freely. This federalised fragmented structure is precisely what allowed an artist such as Pavlović to flourish. And it is also partly why the authoritarian arm of the Yugoslav state could be so inconsistently applied when it came to the arts: after the bunkering of The Ambush, Red Wheat saw Pavlović returning to the same well, covering the same period of history in a near-identical style.

Just as in The Ambush, there’s something of a western about Red Wheat. Both are set in rural towns far from urban centres, and might as well start with the phrase ‘a stranger comes to town’, though in place of gunslingers are Party apparatchiks. If the coming of the railways represents the coming of civilisation in traditional westerns, then the coming of socialist ideology represents the same in Pavlović’s work. But his concern is with its inability to create the utopia it promised its citizens, capturing the chaotic and often brutal process in which peasants and the marginalised became Yugoslav citizens.

Red Wheat stars Rade Šerbedžija (familiar to Western viewers as Mysterious Foreigner or Mad Russian Scientist in various Hollywood schlock, but one of the finest actors of his generation domestically) as Hedl, the slick apparatchik who is sent to set up a Peasants’ Work Collective in a Slovenian village. Hedl stays at a house owned by a terminally-ill patriarch, cared for by his wife and two daughters, and initially helps with the chores, appearing co-operative and gentle. But facing resistance, he gradually turns to coercion, corruption and outright violence, including providing sexual services to the wife and one of her daughters.

There’s something appealingly rancid about Hedl, an absolute snake of a human being, capable of using charm and smarts to get what he wants (it helps that the young Šerbedžija is preposterously handsome) but exceedingly quick to resort to far more nefarious means as soon as possible. If Ivo is a young naïf who receives a rude awakening, Hedl is already battle-hardened and long since disillusioned, but too selfish to care otherwise. Sex—or rather Hedl’s version of sex—is carnal and desperate for both parties (there’s little romance to be found in much of Pavlović’s works). Again, the director deploys an almost identical aesthetic style as in The Ambush, save for the shift to colour photography, though the muddy browns and drab tired trees suggest a world without much of it.

The State of the Dead: On Compromise

Here once more, Pavlović focuses his ire on the construction of national myths, in this case the collectivisation of agriculture, a largely failed initiative that was quickly abandoned, particularly once Tito’s split with Stalin necessitated a different structure of socialism to differentiate itself from the USSR. But the revolution itself, strangely, seems to be absent in Red Wheat. Yes, characters talk about it, but the fervent vision and optimism is nowhere to be found. In The Ambush it is entirely present, imprinted across the film, characters motivated by it, enlivened by it, but also broken by it. The participants in The Ambush are buffeted left and right by the winds of history, barely clinging on at the terrifying pace of change. Everybody seems to have given up already by the time of Red Wheat, those winds dissipating.

Perhaps in this tiny change lies the seeds of compromise for a stubbornly nihilistic auteur like Živojin Pavlović. In The Ambush, interpersonal relationships between characters are motivated and constructed around the revolution, and the change of ideology that comes with it. The film suggests historical developments as having an element of accident, chaos and collective opportunism to them, therefore suggesting there is no credit due to any one thing—and thus the entire structure of order on which a myth is built collapses.

But Red Wheat individualises this concept. A surprising amount of the film’s runtime focuses on the disturbingly manipulative relationship Hedl builds with his hosts—the character’s individual choices largely, in this instance, occurring from his own initiative, whereas few people have any real agency in The Ambush, surprised (well, ambushed) as they are by developments. Thus, Red Wheat suggests a single individual and his greed is responsible for the same mistakes and misery. Does this make the medicine easier to swallow?

After Red Wheat, Pavlović’s work became much less frequent, as Yugoslav authorities put a stop to the Black Wave, of which he was a part, and created a more aggressively hostile environment for filmmakers. Yet, aided by the move to a different republic and with different collaborators, Živojin Pavlović was able to make a nearly identical film after having his previous work bunkered, an exile in his own land, somehow evading immediate scrutiny and flying in the face of open compromise.

Thanks to Mina Radović for providing research materials.