Let’s admit that something is possible in Italy today that Hollywood was unable to accomplish: the awareness of that lumpen-cinema, effecting, under the mask of old forms (hence without rejecting its popular character), a euphoric work of deconstruction.

Part of the “euphoric work of deconstruction,” to use Daney’s phrase, in mid-century Italian cinema was its reconfiguration of the role of the director. Italian production companies would hire multiple directors—to reshoot, re-edit, and recombine the footage on a single production—at a time when Hollywood leaned into singular auteur-directors as a new way to market its movies. Italy’s filmmaking practices had always left room for more discord than Hollywood’s—its dubbed audio and embrace of non-professional actors, for example—and by the late 1950s it had made a habit of importing out-of-work American directors, teaming them up with Italian ones to obtain government funding. The Americans’ participation levels varied widely: André De Toth referred to his overseas work as his “vacation,” letting the second unit do the bulk of the filming, whereas Edgar G. Ulmer seemed to helm the production with the same distinction he brought to his Hollywood B-movies. The rare films that did feature meaningful input from both directors often involved the work of Mario Bava, who co-directed films with Jacques Tourneur and Raoul Walsh, two poster children for auteurism now forced to compromise—compromising the films in the eyes of those auteurists—by the presence of another great filmmaker on set.

The Giant of Marathon (1959), directed by Tourneur and Bava, and Esther and the King (1961), directed by Walsh and Bava, are too polyvocal to be claimed squarely by enthusiasts of any of the individual directors. Chris Fujiwara, in his 1998 monograph on Tourneur, calls it “a symptom of the period,” and Bava biographer Tim Lucas dedicates short chapters to these works-for-hire in between deep analyses of Black Sunday (1960) or The Whip and the Body (1963). It is a reasonable reaction to these flummoxing sword-and-sandal films: their flat dramaturgy make the traditional auteurist scavenger hunts for repeated themes and visual trademarks appear belabored. How can artistic agency be assigned within these supposed failures? Sequences were re-edited without the directors’ input, dubbing could change the entire story’s meaning, and anyone who knew which director did what is either dead or prefers not to talk about them. Instead, these films must be approached as they appear to a viewer—as fractured objects that demand a fractured response, but ones in which the artists’ unique voices mysteriously arise.

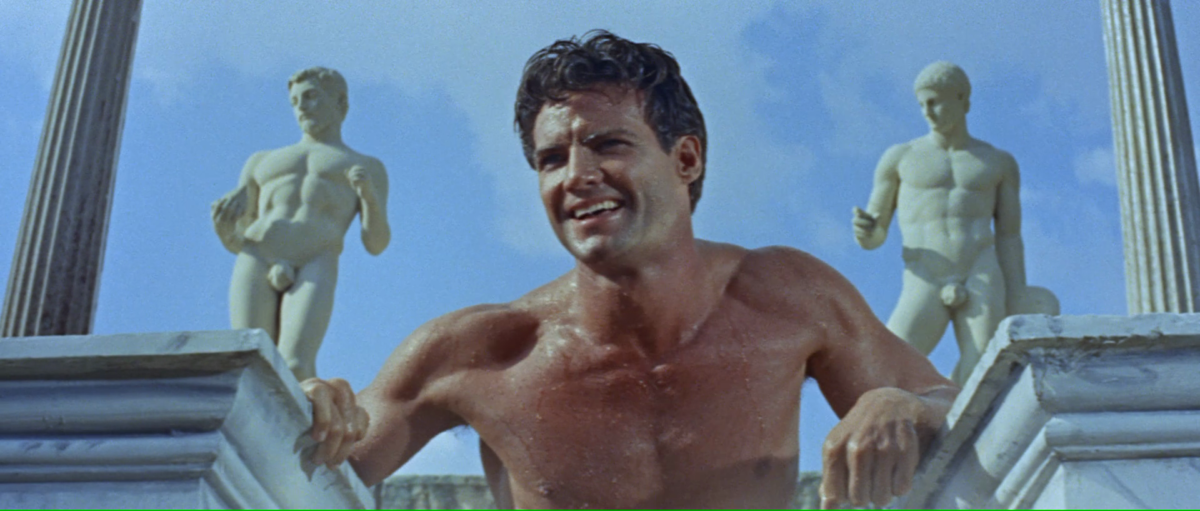

Even the title of The Giant of Marathon exposes the fracture: it was also released as The Battle of Marathon, a change which betrays Bava’s main contribution to the film, its large-scale battle scene composed of a handful of extras superimposed multiple times within the same frame. The fight is between the Athenians and the Persians over the former’s democratic city-state, but the looseness of the narrative encourages a more abstract viewing of the action. In its most striking shot, soldiers stream out from a single distant point in five bands, resembling rays of sunlight—nearly a visual metaphor for the image’s own grandiosity. Each band was shot as its own exposure, so the seams between them vibrate, evidence of the handiwork Bava employed to achieve the effect. Why does he choose such obvious artificiality instead of the kind of subtle, believable suggestion that Tourneur was so praised for in Cat People (1942) or The Leopard Man (1943), in which he transformed humans into animals via a few clever shadows? Perhaps for the same reason that Bava’s chilling zooms in A Bay of Blood (1971) move with the unmistakable jitter of his hand cranking the lens—to turn a film about our most cosmic fears into an object that was once held in his hand. Or perhaps it is for the same reasons that Tourneur had matured from the baroque ornaments of the RKO films to the grand, bleak grays of Night of the Demon (1957) and The Fearmakers (1958), in which the horror is no longer a mythical power but the bureaucratic men in charcoal suits with shifty eyes we see on-screen. While the multiple-exposure is unmistakably Bava’s work, the seams start to resemble the gaps in Stonehenge in Night of the Demon and the “circular streets and radiating avenues” of Washington DC alluded to in The Fearmakers. The shot calls attention to itself, but in an elusive, depersonalized way rather than as a key to the director’s personality. The shot is both Bava’s and Tourneur’s and neither of theirs, all at once.

To add to its unknowability, actress Mylène Demongeot claims that Marathon’s producer, Bruno Vailati, known for his undersea documentaries, shot three-quarters of it, including the aforementioned action sequences. Trying to piece together an account of the film’s production begins to reflect the indeterminate history of its mythological source. The same holds true for Esther and the King: co-written, co-produced, and co-directed by Raoul Walsh, yet not mentioned in his autobiography. Walsh’s longtime passion project, the adaptation of the Biblical book of Esther, was originally planned as a big-time Hollywood production, in the vein of Ben-Hur (1959) or Spartacus (1960), but an ongoing writers’ union strike relegated it to a co-production with Italian company Galatea, to be filmed in Rome’s Cineccità studios. Esther’s story already had a rich history of being reinterpreted in the Jewish tradition of the Purim spiel, in which synagogues put on comedic stagings of the defeat, by Esther and her cousin Mordecai, of the manipulative Haman. (Memorably, I was once conscripted by an over-eager Hebrew School teacher into acting in a breakdancing adaptation of the Esther story.) The screenplay takes liberties in keeping with the spiels, adding a competing love interest for Esther, her fiancé Simon, who fights the King Ahasuerus before they band together to defeat Haman—a fitting metaphor for the compromises reached between Walsh and Bava.

Bava’s artistry is most obvious in the décor and lighting. The saturated hues of the king’s palace—particularly the flat-colored night sky seen from within it—are as lively as any in his solo work. Laced into this visual splendor is a specific disdain for Walsh’s working methods: “I always had the final assembly in mind, so that nothing was ever wasted, not so much as a meter of film,” said Bava. “But the Americans—Walsh, for example—‘covered’ themselves, as they say. They didn’t concern themselves with being creative, only with covering themselves.”Tim Lucas, All The Colors of the Dark, p. 342 For every scene in which Walsh seemed unconcerned with this bravura of “being creative,” Bava injects colored scrims or dark shadows on the outside edges of the frame. Walsh has always been one to deny virtuosity, so to see such obvious beauty in one of his films feels almost ironic: as if Walsh were commenting on Bava’s mannerism while Bava poked fun at Walsh’s minimalism. But Bava’s comment betrays a misunderstanding of Walsh’s art, especially by the time of Esther. Walsh had reduced his filmmaking down to the point where any control beyond the point of shot selection was irrelevant, creating a vacuum that allowed for the introduction of another director’s sensibility.

An early scene in which Esther is separated from Simon presents an elaboration of a gestural motif from High Sierra (1941), but entirely devoid of the earlier scene’s structural solidity. Both follow the same outline: lovers (Humphrey Bogart and Ida Lupino in High Sierra; Joan Collins and Rik Battaglia in Esther) share a shot-reverse shot of tenderness, a vehicle enters (a bus; the king’s calvary), the woman exits the scene with that vehicle, and finally the man leaves of his own volition. High Sierra follows a classical construction, in which each gesture is balanced by its opposite. The lovers embrace by their car, and they embrace in mirror image by the bus; the camera pans to the right as the bus drives away, then pans to the left as Bogart makes a U-turn and drives off to the left. If the High Sierra scene is a circle, the Esther scene is a line: each gesture (besides a few pointed exceptions) moves from the left to the right, escalating the momentum rather than sealing itself up. The establishing shot of the couple features a sweeping dolly from left to right, before a cut reveals the king’s soldiers arriving from the left. A soldier briefly moves to the left to snatch Esther, then carries her on horseback to the right. As a sword fight ensues—spiraling rightward, of course—and causes chaos in the town, Simon and his companion leap into tall grass. The consequences compound, until a commanding soldier declares, “Sack this village. Flog every man, woman, and child. Let it be done to all the Hebrew settlements,” as his henchmen scatter. The scene’s cuts are haphazard, snipping off movements partway through: in that sense, Walsh seems less in control than in High Sierra, in which one could imagine him presiding over each cut in the editing room. Through such noise, each shot shares a directional thrust, moving from domestic communion to wide-scale terror, revealing that Walsh has not abdicated artistry, but rather that he has distilled his filmmaking to the simplest elements, leaving room for others—Mario Bava, in this case—to synthesize their sensibilities with his own.

Vladimir Nabokov, a chess lover as much as a writer, once extolled chess problems over actual matches—the handcrafted puzzles representing a careful, direct connection with their creator, instead of the messy competition of an actual match. He compared the former to poetry, and many movies—at least, ones by directors such as Tourneur, Walsh, or Bava—fit the description as well. Watching The Giant of Marathon and Esther and the King, however, is more akin to watching a chess match, a fierce competition offset by the complicity of the two players to create a spectacle that neither can control. Moving closer to these films doesn’t bring one closer to a singular personality, but rather the synthesis of multiple clashing ones. Hastily-sketched as they are, these movies both have to do with the mechanisms of governance: Marathon with the protection of Athens’ democracy; Esther with the choice of a queen. And by some oblique workings those subjects seem to be grafted onto the conditions of their production. Marathon, Esther, and the countless other Italian films of the era reveal alternative modes of creating and relating to cinema—and popular, unpretentious cinema at that. They provide a model of directing that is not dictatorial, or even democratic, but materialist in its synthesis of the art of disparate filmmakers. A deconstruction of Hollywood, yes, but more so a reconstruction, that flourished briefly in Rome, and whose completion we still await.