Lonely remote churches

where the soprano voice of the Easter Passion

had never in helpless love twined itself round

the gentler movements of the flute.

for Oliver, I o U

I.

In the beginning was the Word, but before that? The most obvious answer would be silence, but that does not hold under scrutiny. For there to be silence at all, it seems that some sort of speech should have preceded it. Only after the Word has appeared had its absence become a possibility; in much the same way our absence is only logical after our birth. Before that we are not absent, merely nonexistent, which makes all the existential difference. In much the same way silent cinema was not known as such during its period of dominance. That epithet – silent cinema – was only bestowed upon it after the first talkies. The question — why is there something, instead of nothing? — can only be asked at the very moment a ‘something’ exists (presumably even by that very something). So whatever was there before the beginning would not have been silence.

The same can be said for particular silences. Someone on the other side of the world that has never met you cannot be said to be silent towards you. In order for there to be a silence between two (or more) persons, a form of contact between them must have taken place or — another possibility — the sender and receiver of silence need to be in a kind of proximity. Interpersonal silence needs a known subject for it to be successful.

Another question entirely is the interpretation of a particular silence. The effect of its silent existence, its facticity, seems to be entirely dependent on the unspoken words that called it into existence in the first place. But since these words are unspoken, one could only guess what they were and, then again, this guess would have to be informed by the answer or plea inherent in the words spoken right before those left unspoken; that is, the desire that manifests itself through the last words spoken. We interpret the silence by the words that have come before it.

The medium of cinema lends itself to the expiration of these particular silences because of its focus on the human face. Especially when this face awaits an answer. In silence. When scrutinizing the effects a particular silence has on somebody, their face is the gateway to subjectivity.

All this philosophical wordplay paves the way towards the question: what do we talk about when we talk about the silence of God? What desire is manifested in our pleas that provoke this particular silence and what answer can be read into it? By explicitly dealing with these themes, Ingmar Bergman’s Winter Light (1963) is an ideal film through which to continue our wordplay in the hope of recouping the losses we have suffered while waiting for His answer, against all odds.

II.

There is an undeniable pomposity to Bergman’s oeuvre. The stakes always seem to be immensely high, but only because of the protagonist’s yearning for them to be as such. Everything turns out to be existential in these films, which, depending on one’s mood, can come across as very poignant or outright ridiculous. If one denounces the claim in which stubbing one’s toe can be an exemplary corroboration for life’s meaningless in late modernity, one will not find much to praise in these films that time after time seek to build up, in ever varying forms, this case against existence itself. Nevertheless, they do so in such a rigorous manner, serving as paragons for a certain kind of intellectual European tradition: “the argument against life” in all its splendor and, more compellingly, its shortcomings.

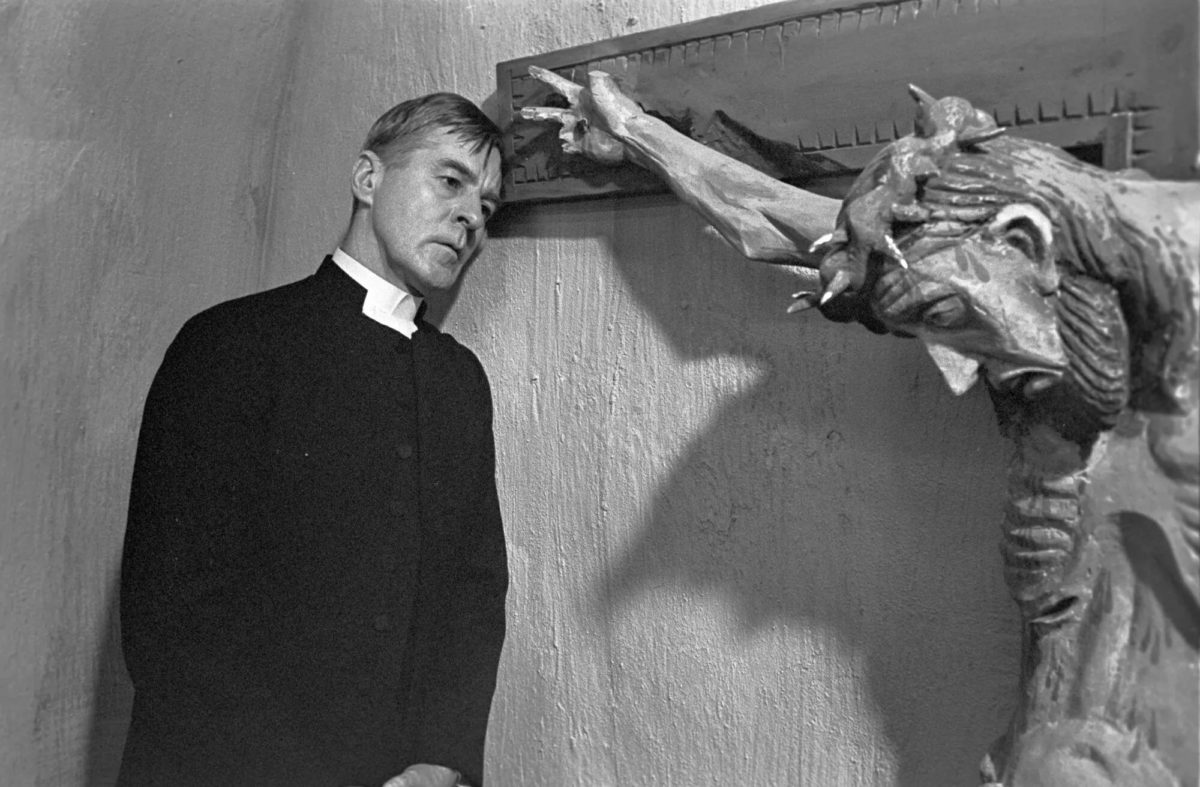

Bergman plunges right into the heart of the matter. The matter being a Holy Communion led by a protestant pastor. Opening with a frontal shot of our protagonist, Tomas Ericsson (Gunner Björnstrand), the stark black and white cinematography deepened by the Geneva Gown that Tomas is wearing, we are welcomed by a man who is on the verge of a nervous breakdown. He performs his duty for only a handful of parishioners. Despite his loud tremolo and imposing gestures, we, as viewers, cannot help but wonder if this man believes the liturgy he is now proclaiming. The nature of this dubiety and the possibility of it being shared between (and thus possibly lifted by) two persons will be at stake in the runtime of the film, whose events take place in the few hours between morning and afternoon services. As for which two persons, they could be either the viewer and Thomas, or the latter and Ingrid Thulin’s Märta, the woman who’s been taking care of him for some time now, or even more abstractly a shepherd and his flock

After the service, a wife and her husband ask to see the pastor. Having read a news article about China’s nuclear power and its potential to destroy the whole planet, the husband (played with remarkable frailness by Max von Sydow) has lost all incentive to keep on with this game called life, his wife being pregnant with their third child notwithstanding. As is often the case with those of us who are going through the motions of life and the intellectual reasoning that necessarily underpins it, it is just enough not to doubt ourselves too much. It takes another one’s crisis to instantly blow away the house of cards we have been inhabiting. Unable to offer the man anything other than clichés for help, the pastor is forced to face the truth of having lost the invaluable foundation underneath his faith. Deprived from this, everything that comes out of his mouth has lost its significance, its weight, and merely floats in the air as flatus vocis; mere words that no longer correspond with a lived reality. The man, sensing the emptiness of these words, leaves the church never to return again, instead taking his own life underneath the tree on a nearby riverbank.

III.

Something happened to shake the pastor’s faith so thoroughly. His wife died. Not even that long ago, although it may seem unbecoming to talk of consequential chronology with regard to death, which is so absolute and total. The passing of this woman has shaken the core of this man as nothing else had been able to do before. The very private reason for this failure of faith counterpoints the more abstract reasoning from which the pastor could not walk his parishioner back. What is more ludicrous: to lose one’s faith because one feels alone in his suffering or to lose it because of the sense we are all together in our suffering? Whatever our answer may be, the silence of this God we have attributed with fatherly characteristics chimes equally loud.

And yet He might be talking to us, albeit not in the way we want Him to. The propelling plot motor of Bergman’s films until Persona (1966) is that of which is informed by a conflict between the rigorous resignation of the intellect and a more permissive attunement to the sensuous perception of the world. The juxtaposition is not presented as clear-cut in the movies, but the struggle between and mutual contamination of these polar opposites is always playing itself out somewhere in the forefront. The central question is: how does man live in the world? With it or against it?

Being very much of his time, Bergman divides these two stances expectedly between the sexes. The women mostly represent life’s complicity with itself, whereas the men distance themselves from it, yet the outcome is much less predictable than this initial set-up would suggest. Bergman’s women need to operate between the narrative constrictions of the muse who ties the suffering artist (or his stand-in) to the world surrounding them; they enunciate an intelligence which vastly exceeds this proscribed division of roles. Through the undeniable candor of their performances, the female actors transcend the limitations by which their characters were conceived and as such synthesize the dialectic of which they were presented as mere theses. The female characters shine in part because they understand very well the role they have been given and how its truth exceeds the meaning Bergman has ascribed to it.

In Winter Light, Ingrid Thulin imbues her portrayal of the schoolteacher Märta with a truth, which ridicules the existential dread of our Doubting Tomas. Through the radiance of her face, epitomized by the letter she reads aloud for us – to us – something that lies outside of Tomas’ despair is revealed. Breaking the narrative tightness of the film and the dramatic rigor with which it is told, Bergman shows her reading the letter in an almost intimately constructed monologue on what appears to be a soundstage. A close-up as if in a confessional. In doing so, something that lies outside of Tomas’ despair is revealed. There’s a crack in everything… Bergman has claimed the close-up “the height of cinematography”https://www.bfi.org.uk/features/ingmar-bergman-faces-close-ups and Marta’s reading of the letter is a keen example of what he meant.

“Bergman’s cinema is a cinema of faces” reads a lot like “Bach’s music is a music of notes”, but this obvious statement is nevertheless necessary to think about the specific quality of these faces that texture his movies. Compare them with the faces of Pasolini’s films, specifically his Gospel According to Matthew (1964). The faces that inhabit Pasolini’s retelling of the word of God, through Gramsci to Marx, are those of peasants and seem in perfect harmony with their environment, which consists of the rocky landscapes of an imagined Palestine. Every single one of them is a testament to the hardships of a life lived with and against nature, the essence of monotheism with its promise of transcendence over illness and death.. These are the faces of the premodern man who craved to be saved from the suffering of his flesh. Cut to 2000 years later and how primordial these faces seem compared to the ones we have been accustomed to in films. Nature has been overcome, if only in our faces. We have undone ourselves from nature so efficiently that our faces have become empty canvasses whereupon we easily project despair.

Yet Thulin shows us a possible way out of our conundrum through the candor and courage of self-regard she invests in Märta. One line in her monologue is easily glanced over, surrounded as it is by unbearably poignant emotional disclosures: “One thing in particular I’ve never been able to fathom; your peculiar indifference to Jesus Christ.”

IV.

Märta writes these words. If we believe God to exist, at least this particular one, we should not circumvent this most unusual of all occurrences; the fact that at one point He found it necessary to become flesh to save us. If the Gospel be the Word of God, this word was at one point spoken by a being as fully human as we are. This is the only point where theological and human history intertwine. The Greek gods had been given human psychology yet had remained fully alien in the way their immortality deprived them of the quintessential human experience. Only the Hebrew God decided, according to certain sources, to become human himself to save us from ourselves, our mortality. He had to doubt his own existence: “Father, father, why have thou forsaken me?” Depending on the tradition you decide or want to believe, this statement could be read as an ultimate act of love. It is at least an act of communication. Jesus’ doubt followed by his resurrection and eventual ascension, are the last known ways in which God talked to man. From then onwards he remained silent.

Maybe he just said all he had to say. If the first covenant between this God and his people were the Ten Commandments, it is with the breaking of the bread and drinking of the wine that Jesus talks about a new covenant. The focus here is on the activity of sharing a meal between them. One could understand the transition from the Old to the New Testament as a shifting of our focus from a vertical relationship between us and our God to a horizontal one between ourselves in the name of God. The concept of caritas — the Christian love of humankind — amounts to a new, positively expressed focus against the negatively formulated focus of the Commandments.

As a benevolent father, God has set us free to fetch for ourselves. The new command of caritas is the result of his incorporation and subsequent transcendence of our human condition.

God as the benevolent father has given us all the guidance possible after incorporating our own subjectivity and transcending it. Märta knows this and sees the fault in Tomas’ impossibility of recognizing the shift that has taken place. His focus on an abstract, decidedly Platonic, struggle with God as an idea: this is his misunderstanding of his role as a shepherd of men, a misunderstanding of the kind pointed out by philosopher Blaise Pascal when he noted the heart has its reason(s) of which reason knows nothing. The lived experience of religion (in faith or in despair), will not see the questions inherent to this experience, answered by the abstract reasoning of philosophical inquiry. Once more Pascal (in his Mémorial): “GOD of Abraham, GOD of Isaac, GOD of Jacob/not of the philosophers and the learned.”

Love will definitely not conquer all or be the solution to everything. But what Märta understands and sees clearly is how Tomas is looking for the answers he needs in the wrong place.

V.

Tomas’ crisis rests on a misinterpretation of the silence for which he holds God accountable. Not only is this silence not the evidence of his non-existence, but the silence is not even there. In his search for a sign of God’s existence, Tomas resembles the minister in the Parable of the Drowning Man. During a flood the devout minister becomes stuck on his roof and refuses help from people passing by in boats three times, declaring God will find a way to save him. Ultimately drowning because of the rising tide, the man enters heaven and asks God why He did not send any help only for God to answer He had sent him three boats. “I can’t help you, if you don’t help yourself.” In focusing on the perceived silence, Tomas neglects to notice the signs flashing before his eyes.

All this is brought to climax in the most beautiful scene in Winter Light (notably singled out by Andrei Tarkovsky in Sculpting in Time). Having received the news of Persson’s suicide by a group of children, Tomas hurries to the scene of horror to find the lifeless body. This scene on the riverbank is conceived, per Tarkovsky, “all in medium and long shots, nothing can be heard but the uninterrupted sound of the water.” This is a remarkable deviation from the more constrained camerawork throughout the rest of the movie, which mostly takes place indoors. This opening up of the spatial contours of the story offers a promise that Tomas ultimately fails to deliver. Taking a step back and opening himself to more than just the cloggy preoccupations of his mind would have put things into perspective. An outside view does not diminish the importance of our doubts and struggles but contextualizes, reworking them into something new.

The genius of this sequence, in all its narrative tragedy, is the “uninterrupted sound of the water.” The world is constantly speaking to us: through other human beings, through its waters and skies.

There is no silence here, if only we know how to listen.