It was during Ernst Lubitsch’s So This Is Paris (1926): the placement of the intertitles, the tasteful emphaticness of the actors, the dexterous manner in which the camera cut between two Parisian apartments that look perfectly into one another across the way. Lubitsch embraced the advent of sound as early as 1929 with The Love Parade, which invites sophisticated pockets of silence amidst its technical derring-do, such as simultaneously directing the players of a musical number across two identical sets so as to preserve the necessary rhythm and interplay. But even in 1926 one can detect an infectious restlessness that cannot be contained by the silent vs. sound cinema binary. Can we still hear something that’s technically without sound? Lubitsch seemed to think so.

This doesn’t only encourage a recalibration of critical preconceptions of the silent era, which was quickly and effectively ushered to the dustbin when sound became the norm—sound cinema itself is also an active participant in this mercurial discussion. When a comparatively modern filmmaker willingly eschews sound, we can easily draw a line from this isolated decision to the tradition of the silent cinema. Various iterations of the medium’s past are in constant conversation with the ever-shifting present, and we should locate the significance of these interactions before they’re lost to further technical advancement, as well as the encroaching erasure of film’s history.

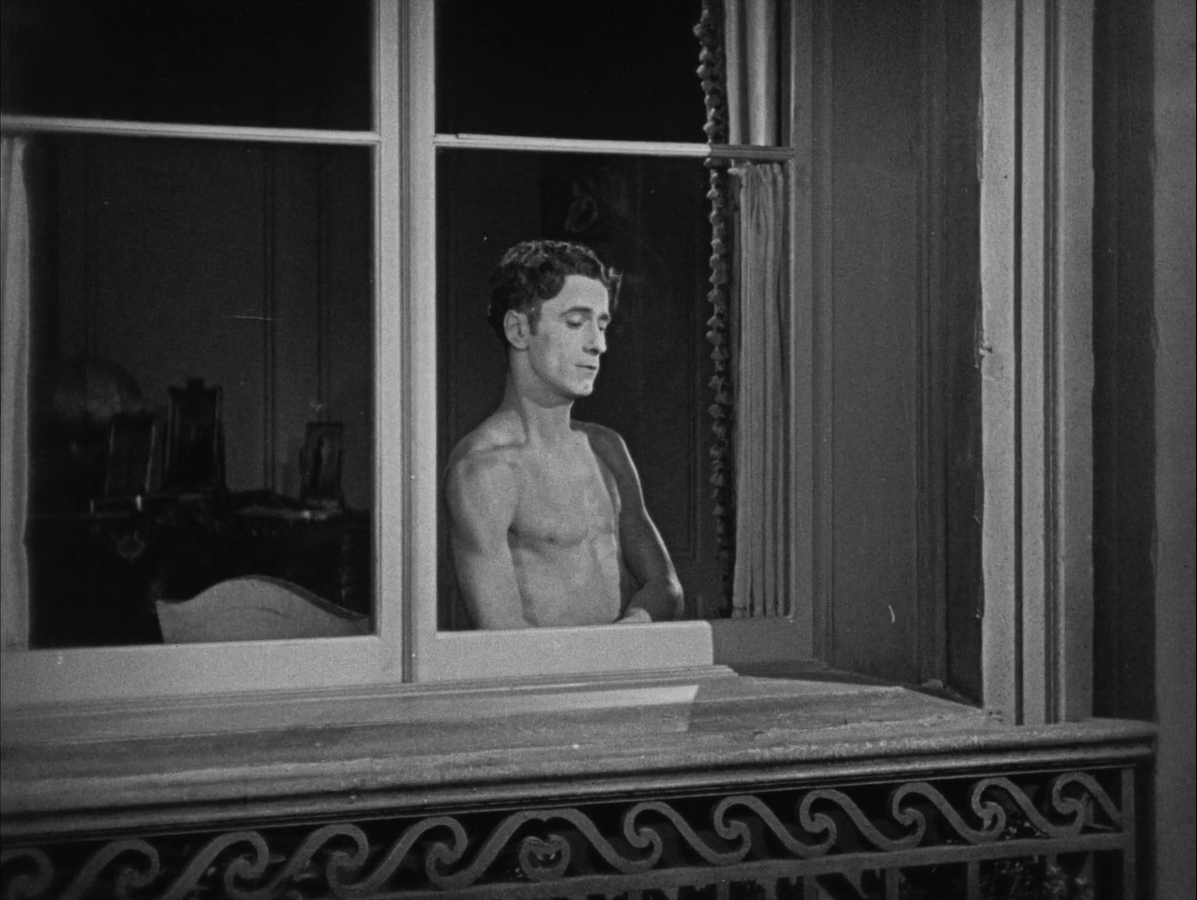

Similar to these ideas on Lubitsch, Cláudio Alves delves into the work of Dimitri Kirsanoff, whose abilities as a classical musician manifest in how he formally constructed his 1926 film, Ménilmotant, which, according to the author of this piece, exhibits a “silent musicality.” It is not uncommon for the silent cinema to impart a lingering sensation that approaches the auditory.

The dissection of a director’s formal rigor continues with Ioanna Micha’s cataloguing of Stanley Kubrick’s sadistic molding of thematic and literal silence in The Shining (1980). This extends to the soundtrack, the script, the editing; Kubrick comprehended the discomfiting qualities of the perfectly inserted gap.

Ruairí McCann uses Artavazd Pelechian’s Nature as a jumping-off point to penetrate the past and present of the cinema in a montage-heavy work that effectively and wittingly silences the human element at choice intervals.

Drawing upon a rich tapestry of artists—with experimental filmmaker Peter Hutton at the center—Anuj Malhotra posits that perhaps the answer to the eternal “why” that resounds across all mediums can be located within the silences.

Using the heavy religiosity of Ingmar Bergman’s Winter Light as a template, Michaël Van Remoortere pins down the sneaky metaphysics of silence, applying a critical lens to everyone from the common townsfolk of the film, to God.

Fidally, Ed McCarry elucidates Jacques Becker’s penchant for “dead time,” where the primary narrative is silenced to bring secondary elements to the fore. In doing so, Becker becomes more a chronicler of various lives occurring within and without the frame, rather than a mere storyteller.