D’entre les morts

With the loss of Chantal Akerman and Jacques Rivette (and de Oliveira and Zulawski!) this has been a sad year for le cinéma d’auteur. Chantal’s death was completely unexpected – a shock – the reason why it has taken this blog so long to come up with an adequate response (we’ve now decided to dedicate this year’s Summer Film School to Akerman; stay tuned for more details on that event). Rivette was, with Godard, Varda and the less prominent Jacques Rozier (Adieu Philippine 1962), the last living member of a once popular bande à part. At eighty-seven and suffering from Alzheimer’s, his passing did not leave cinephiles in the same state of defeat and bewilderment that greeted the Akerman news and failed to arouse much interest from the mainstream media (his was certainly the biggest snub in the Oscars’ “In Memoriam” reel). Also, while the disappearance of Chantal had something final about it – the end of an era, call it ‘cinematic modernism’ – the passing of Rivette somehow seems less specific, more ephemeral (the end of postmodernism?).

Already a lot of time has passed since Rivette’s death was announced on January 29, but I cannot shake the feeling that he will return, in some shape or form, perhaps hovering ghostlike over Paris, like those phantom ladies of what is still his most beloved film, Céline et Julie vont en bateau (1974). The reason I want to believe in Rivette’s return in spectral form may have something to do with the special place in his cinema reserved for Poe and The Count of Monte Christo, for Cocteau, keeper of the Zone, or for Hitchcock’s revenant tales, Rebecca and Vertigo. It might also be because of his planned but never realized four-part series bearing the Balzacian/Nervalian title Scènes de la vie parallèle, tales about “Filles du Feu” searching for a mysterious jewel that will keep them alive on earth beyond the time of Carnival, the 40 days allotted them between the last new moon of Winter and the first full moon of Spring. Perhaps it’s because of that mischievous twinkle in his eye, the nervous, apologetic smiles and shrugs that always seemed to promise, well, something out of the ordinary. Or maybe the reason is the unusual secrecy of the man, about whose private life hardly anything was known (the news that he had remarried in his later years came as a complete surprise to me, difficult to reconcile with the image of the eternal recluse who spends his days reading and watching movies), and who had a tendency to disappear when he wasn’t working.

If he often disappeared, he always came back. In fact, he was something of a comeback king. His first film, Paris nous appartient, shot during the summer and autumn of 1957, was almost abandoned when the money ran out. It was saved by the success of Truffaut and Chabrol’s début features, beating Rivette to the punch by becoming the first films by Cahiers cinéastes. Editing on the film was completed in 1960 and by the time it finally came out late 1961, Godard had already released his first three films. Paris proved one of the most unpopular early New Wave films and it would take Rivette five more years to complete his next film, Suzanne Simonin, la Religieuse de Denis Diderot (1966). That film, based on Diderot’s posthumously published novel was, fittingly, another delayed release, sidelined after a negative script report from the censor and first produced as a play (financed by Godard for Anna Karina). After a ban imposed on the finished film by the Gaullist minister of information and a storm of public protest led by Godard’s letter to minister of culture André Malraux, La Religieuse was eventually brought to theaters in the summer of 1967 and, because of the controversy, did more than respectable business. Rivette then set up the more experimental L’Amour fou (1969) with the players of Marc’O’s theatre company and no stars, a film that turned out three times as long as its director had promised producer Georges de Beauregard. If that film and the next one, the 13-hour film fleuve Out 1 (1970), a film only screened once in that untruncated form in an art centre in Le HavreThere has been a lot of confusion surrounding the original form of Out 1, which screened in its long form (known under the subtitle Noli Me Tangere) at Cinematek in a program curated by Courtisane and was recently released on DVD both in Europe (by Arrow) and the US (by Kino Lorber). Film historian Robert Fischer has found that, although the original idea for the film was to do four parallel feuilleton stories linked at the beginning of each episode by still shots in black and white, resuming the action of the previous episode, the legendary showing in Le Havre was of a continuous but unfinished work print, a rough assembly. The first finished version of the film was the condensed 4-hour Out 1: Spectre released in 1972, with the black-and-white stills serving as a recall, pause or connection. The long version was not formally completed until 1990 when German television offered to buy it for screening as a serial. The full version of Out 1 was finally shown as a serial on the Paris Première cable channel in the early 1990s. Like the ‘Filles du feu’ series to follow, Out 1 was originally conceived as a series film, with Out 2 a love story and Out 3 a story of political corruption. See Tony Rayns’ report, “’Out’ in the Open” in last month’s Sight and Sound., did not bury his career (and that of its producer, Stéphane Tchalgadjieff) the impossibly baroque one-two of Duelle (une quarantaine) (1976) and Noroît (une vengeance) (1976), parts two and four of the Scènes de la vie parallèle, did. Duelle – a film that looks like Sternberg, Demy and Fassbinder got together to film Val Lewton’s The Seventh Victim (1943) – ran briefly in a single Parisian theatre while its director was busy editing Noroît. After the critical and commercial failure of the former, the latter – like Straub-Huillet or Marguerite Duras teaming up with the Renoir of Le Carrosse d’or (1953) and the Welles of the Shakespeare films to remake Lang’s expressionist swashbuckler Moonfleet (1955) – was never released. After starting the third film, actually part one of the series, Marie et Julien, with Albert Finney and Leslie Caron, Rivette, exhausted, disappeared, having suffered a breakdown, like a heroine in Brönte or Wilkie Collins. He resurfaced for another film maudit, Merry-Go-Round, an improvised mystery thriller starring a terminally depressed Maria Schneider and Warhol superstar Joe Dallessandro during his heaviest heroin addiction phase. That film, shot in 1977/78, was only released in 1983, shortly after another comeback with the no-budget Le Pont du Nord (1982), a street film shot on 16mm in the twenty arrondissements of Paris. Critic Serge Daney called that film “a returning in the double sense of the term … Returning to the circuit of cinema; returning in, retracing, his steps. Returning and a new departure.” The return of Rivette led to late-career prestige with his most classical and well-received films yet: La Belle Noiseuse (1991), a 4-hour rumination on the theme of Susanna and the Elders via Balzac’s Le Chef-d’oeuvre inconnu (1831), also released in a more audience-friendly Divertimento edition; Jeanne la Pucelle (1994), a two-part Jeanne d’Arc anti-epic, Rivette’s most expensive film; Secret défense (1998), another return to Hitchcock and Lang; Ne touchez pas la hache (2007), a faithful Balzac adaptation. The late career also gave us new chapters in Rivette’s ‘comédie humaine’ that were actual comedies: L’Amour par terre (1984), Haut bas fragile (1995), Va savoir (2001), variations on classical (musical) comedies brought back to their origins in the commedia tradition of Goldoni, Marivaux and Musset.

Daney was right in predicting that Rivette’s return in the eighties would entail a retracing of his steps, a search for new ways to take off from material first tried in Out 1 and Céline et Julie. Like Frenhofer revisiting his abandoned masterpiece in La Belle Noiseuse, he also returned to the uncompleted Scènes de la vie parallèle. It was after having watched again one of these returns, Histoire de Marie et Julien (2003), the love story between a mortal and a ghost that would have been part one of the Scènes and made its first retooled reappearance as the end of romance between former radicals Bulle Ogier and Pierre Clémenti in Le Pont du Nord, that I first started thinking about the importance of revenants in Rivette’s work. All the elements that typify the late works, and a large part of his cinema in general, are present in Histoire de Marie et Julien: a literary gothic atmosphere indebted to Poe and Henry James; a mythopoeic blending of dream and reality familiar from Cocteau; the velvety clair-obscur of cinematographer William Lubtchansky; a limited number of characters, very often including a pair of siblings (taken from either Les enfants terribles or The Seventh Victim); an equally constrained number of sets, giving the sense of an emptied-out Paris (qui dort?), crucially including one of those minutely dressed, entrapping townhouses or banlieue mansions with at least one locked room and a hidden compartment containing treasure; a pair of powerful, semi-improvised but faultlessly directed performances; a fluid mise en scène with blocking and continuity in function of the actor’s rhythm and movement, but with a tendency towards creating aperture framings when the camera stays behind as a character walks through a door into a hallway, and an opening up of offscreen space in surprising, sometimes startling ways (all those ghostly characters drifting into the frame from zones unseen). In the story, Julien (Jerzy Radziwilowicz) has a dream about a woman he meets in a sunny park (a favorite Rivettian location since the Montmartre opening of Céline et Julie), Marie (Emmanuelle Béart), a woman he had met at a party, fallen in love with and then not seen for a long time. The dream ends in horror when Marie pulls out a knife and stabs him, but that doesn’t prevent Julien from experiencing a happy sensation of surrender to chance and fate when, immediately upon awakening, he runs into her in the street. When she disappears after a night of lovemaking, he tracks her down, finds her hiding out – like Judy in Vertigo – in a desolate hotel room (another preferred setting) and convinces her to move in with him in his fairytale manor with a winding staircase and a jingly cat called Nevermore (who likes to look straight into the camera), where he spends his days mending antique clocks and working out an extortion scheme involving a fake antiques racket and a mysterious woman monikered Mrs. X. After a strange series of events, including Marie’s obsessive ideas for redecorating the attic room once occupied by Julien’s former mistress (a variation on the Bluebeard theme central also to L’Amour par terre, and on the James short story, ‘The Romance of Certain Old Clothes’ that was one of the inspirations for Céline et Julie), it turns out that Marie is a revenant. She committed suicide because of an earlier amour fou and has now come back to reenact her suicide by hanging, just like Jean Brooks in The Seventh Victim. Julien learns all this from Madame X., whose sister (the sibling theme again) also committed suicide and also came back. Contrary to Madame X.’s final acceptance of her sister’s deed, however, Julien is not prepared to let Marie go.

I’m not prepared to let Rivette go, because we’re a long way from being done with him. So revenons-en. The aspects of Rivette’s cinema I want to discuss – the role of the theatre, the conflation of classicism and modernism, the influence from surrealism and existentialism and the forking-path connections to Argentinian master-plotters Borges and Bioy Casares and the émigrés who helped establish their reputation in Paris – are all deeply entangled in the period in which the films were made. Therefore, as with Out 1, some patience will have to be involved in sitting through it all…

Votez Rivette!

Praised by his lifetime friend Godard as the most important member of the Cahiers côterie, Rivette has yet to receive the kind of critical attention or name-recognition gained by most of the other members of the New Wave, this despite a 40-year long career and an extremely coherent oeuvre of twenty films. As Adrian Martin reminds us, we should qualify such coherence by stressing that “the development or evolution of a film artist’s work…often takes an ‘indirect aim’.” It is in a roundabout way, then, often by returning, that Rivette has managed to establish a ‘circulation’ between his films that at times achieves a Balzacian density. A fun auteurist game: try to look for clues to the next film in the previous one: Duelle quite obviously leads to Nôroit, from Jacques Tourneur to Cyril Tourneur, but was Rivette already thinking of his final film, 36 vues du Pic Saint-Loup (2009), when he has Michel Piccoli, in La Belle Noiseuse, comment on the lovely view from said mountain? Did he know he was going to do La Belle Noiseuse as his next film when in Bande des quatre (1989) he has Benoît Régent’s inspector refer to a stolen painting with that title by Frenhofer, the unknown master to Poussin? Was he already preparing for the Brönte adaptation Hurlevent (1985) when he named the two heroines of L’Amour par terre Anne and Charlotte? And perhaps most intriguingly, can we see La Belle Noiseuse a response to the wager laid down by Serge Daney in Claire Denis’ beautiful directorial portrait, Le Veilleur (1990), to engage more directly with the corporeal, the sexual? At times Rivette can even be found to create continuity with another’s oeuvre, like when Le Pont du Nord resumes a character and storyline from Fassbinder’s Bulle Ogier-starrer Die Dritte Generation (1979). One form of continuity is that most of these films star the great faces of French cinema both Nouvelle and new: Rivette – a ‘director of the Woman’ if there ever was one – was especially enamored of Bulle Ogier, Juliet Berto, Jane Birkin, Geraldine Chaplin and, more recently, Emanuelle Béart, Nathalie Richard and Jeanne Balibar, and loved the idea of the female team-up, like Marilyn Monroe and Jane Russell in Hawks’ Gentlemen Prefer Blondes (1953). Despite such coherence and recognizability, Rivette is still the most difficult of the Nouvelle Vague cinéastes to pin down: if Truffaut is the skirt-chasing humanist, Rohmer the studious cicerone, and Chabrol the offspring of Hitchcock and Simenon, Rivette is more mercurial even than that recondite curmudgeon Godard, moving effortlessly from austere Bressonian adaptations of classic novels by Diderot, Balzac or Brönte to wild and free experiments with narrative, temporality, ensemble acting and different forms of direct cinema, the closest analogue for which can be found in the theatrical happening, in psychedelic rock or free jazz.

Parterre

It is with the theatre that Rivette’s cinema is most commonly associated. His first feature film, Paris nous appartient, was also the first in a series of six to feature a theatrical troupe at its center, in this case a small amateur company rehearsing Shakespeare’s ultra-dramatic Pericles, Prince of Tyre. His second film, the controversial adaptation of Diderot’s already highly theatrical La Réligieuse (1796)was a play first, acted, like the film, in the unemotional, ‘typed’ manner prescribed by Diderot in his famous Paradoxe sur le comédien (1830). Rivette constantly emphasizes the theatrical aesthetic behind La Réligieuse by framing in the tableau style familiar from Dreyer, frontally and through doors and curtains that are supposed to evoke the proscenium arch, a stylistic practice that would resurface in the later period. It was in his third film, L’Amour fou that he first conceived of the method that would shape the middle part of his career. Convinced that the ‘mystery’ that is as vital to movies as it is to theatre – call it contingency, the pleasure derived from the unexpected or from watching people being people rather than characters – is destroyed when you stick too closely to a prepared script (a ‘symbol of submission’ associated with the ‘dictatorship of producers’ and the system of l’avance sur recettes), Rivette, inspired by his heroes Rossellini and Renoir, decided to ‘cast aside the scenario’ or at least attempt the kind of ‘ascesis of the script’ prescribed by Amédée Ayfre in his phenomenological writing about Italian Neorealism. Taking as a basis a slender tale scripted in collaboration with his then wife Marilù Parolini about the destructive relationship between a theatrical director (Jean-Pierre Kalfon) and his actress wife (Bulle Ogier) – a story based as much on their own relationship as on Pirandello and his disturbed wife Antonietta Portulano – Rivette built the film around the documentary registration of Kalfon’s real-life rehearsals for a production of Racine’s Andromaque, to be shoton 16mm by André Labarthe, the producer of the acclaimed television series of director portraits, Cinéastes de nôtre temps (to which Rivette had contributed a three-part episode on Renoir, Le Patron 1967). Watching this sketchy four-hour film, Rivette’s first with direct sound recording, that plays like the integration of Jean Rouch’s ethnographic camera in a fictional framework or as an illustration, precisely of Bazin’s idea of Rossellini’s cinema as a ‘sketch,’ it’s as hard to tell where reportage leaves off and fiction begins as it is to see where theatre stops and cinema begins.

Rivette has often declared that he sees the theatre as the subconscious of movies, the only place where the truth of the medium can be found. Reasoning dialectically (or in the manner of Kleist’s essay ‘Über das Marionettentheater’ (1810), a much-cited text: “Must we eat again of the tree of knowledge in order to return to the state of innocence?”), Rivette proposes that if art is about truth, then it is only through patently artificial, i.e. theatrical, means that this truth can be achieved. Thematizing the dialectic between lies and truth in a cinema about cinema would not work in the same way, he suggests; you need the intermediate of theater to avoid making the film appear too self-conscious and affected. This view is close to Godard’s experience, expressed in an interview in Cahiers around the time of Vivre sa vie (1962), that “the closer I come to the concrete, the closer I come to theatre … By being realistic one discovers the theatre, and by being theatrical …” In this context Godard refers not to Brecht but to “the boxes of Le Carrosse d’or,” an allusion to a comment made by an American reviewer that Renoir’s classic film about the commedia dell’arte, that starts and closes as a theatrical performance, is nothing more than a series of Chinese boxes. Renoir took great delight in this observation, as he told Rivette and Truffaut when they interviewed him in 1954. Rivette, who would work as an assistant on Renoir’s comeback film in France, French Cancan (1955), saw Le Carrosse d’or the first day it opened in Paris and stayed in the theatre from the first screening that day until the last. He included Renoir’s comment on the Chinese boxes in his essay on Rossellini, and then borrowed the metaphor for his own films. Noroît, L’Amour par terre, Va savoir and the final act of Céline and Julie are only the most obvious examples of the style of Le Carrosse invading Rivette’s work.

Rivette applied the (meta)theatrical improvisational approach of L’Amour fou on an even grander scale for his next two projects: Out 1 (both in its Spectre and Noli me tangere versions) and Céline et Julie vont en bateau are gothic mysteries in the vein of Paris nous appartient, the former informed by Balzac’s Histoire des treize (1833-39), the latter by two Henry James ghost stories, that feature a Quixotic quest inspired by both Cervantes and Lewis Carroll cutting through long scenes that convey nothing so much as the sheer pleasure of play, of performance, either by a pair or by a larger group. Much of the epic running time of Out 1 is devoted to two experimental companies – managed by two experimental actor-directors, Michael Lonsdale and Michèle Moretti – rehearsing two Greek tragedies by Aeschylus, Seven Against Thebes and Prometheus Bound in the wordless, highly physical manner of Grotowski, captured in the handheld, grainy 16mm of L’Amour fou. Like L’Amour fou, Out 1 was largely inspired by the contemporary artistic practice of Marc’O (Marc-Gilbert Guillaumin), founder of the theatre school in the American Centre of Boulevard Raspail, attended by Bulle Ogier, Jean-Pierre Kalfon, Pierre Clémenti and Moretti who all became part of his regular company. Marc’O’s vision of a new theatre or ‘psychodrama’ inspired by Grotowski and Brook is quite close to Rivette’s conception of a new improvised cinema: both start from the idea of the actor as (co-)creator, not merely the executor of a literary text or mise en scène. For Out 1, actors were invited to come up with their own characterizations within the frame story about a secret society: Jean-Pierre Léaud and Juliet Berto were asked to devise different approaches to the outsider-grifter archetype, while Bulle Ogier was only told that her character is deeply in love with a man who has mysteriously disappeared.

Not only are L’Amour fou and Out 1 invaluable record(ing)s of the rehearsal techniques of Marc ‘O (and other contemporary groups like that of Jean-Marie Serreau), they also introduced the Rossellinian idea of discarding all but the most summary script notes in an open environment of participation and collaborative labor. This idea would most influentially be conveyed by Céline et Julie vont en bâteau, for which both the two lead actresses, Dominique Labourier and Juliet Berto, and the two main supporting players, Bulle Ogier and Marie-France Pisier, got script credit. (Actually the credits mention actors and director ‘conversing’ with writer Eduardo de Gregorio, whose job it was to find ways to link up the film’s base text, Alice in Wonderland, to Henry James’ The Other House (a serialized novel from 1896 that was also staged as a play) and short story ‘A Romance of Certain Old Clothes’ (1868-1885) providing the material for the mysterious goings-on at “7 bis Nadir-aux-Pommes.”) A similar system was used in Rivette’s comeback film, Le Pont du Nord, with Bulle Ogier and her daughter Pascale receiving writers’ credits for having come up with the starting point of the story (borrowed from Die Dritte Generation) and for jamming with Rivette on Foucault’s Punir et surveiller (1975) and situations out of Don Quixote and Jacques le fataliste et son maître. But in this case the dialogue was scripted: by former Cahiers critic Pascal Bonitzer who together with Christine Laurent (and, occasionally Suzanne Schiffman and Marilù Parolini) would perform the same service for all of the films to follow. Still, writing only took place during he shoot, with actors receiving their lines mere hours before shooting. This new practice began with the Scènes, which were minutely laid out by Rivette and de Gregorio, with the actors being invited to contribute gestures and moves rather than situations or dialogue (see here).

Rivette’s films were always focused primarily on the actor, but from Céline et Julie onwards the desire to work with a particular actor or star would become the main incentive for making the film. Here Rivette’s cinephilia reasserts itself. Improvisation would generate moments of delight and surprise when the actor visibly overtakes the character. As Jean Narboni reminds us, Bazin was particularly fond of these moments in Renoir, a director who “directs his actors as if he likes them more than the scenes they are acting.” Rivette was similarly enthralled by moments that “transcend and abruptly suspend the drama,” instances of photogénie that are most often tied to the actor’s presence. (Let’s note here that the Godardian idea that films are first of all a documentary of their shooting, more specifically a souvenir film about the actors, was first raised in Rivette’s essay on Rossellini.) Exploring the continuum between acting and non-acting was just one of the ways Rivette tried to break down conventional dramatic technique. The other, most explicitly established for the Scènes, was to stage the moment when stylized physical action moves over into dance, whether against the backdrop of an actual dance studio, as in Duelle, or as in Noroît as swashbuckling reinvented as a theatrical training exercise.

Duelle and Noroît were also influenced by Marc’O’s particular conception of a musical theatre in which music and dance are used throughout the rehearsal process. The tradition of the Jacobean masque or the Greek chorus is revived in these highly experimental films by having legendary pianist/composer Jean Weiner or prog-rock flutist Jean-Cohen Solal and his trio improvising ‘live’ within the fictional world of the film without having any bearing on the story action, like a reveal gag out of early Woody Allen or Mel Brooks, or like Hoagy Carmichael in To Have and Have Not stripped of the wisecracks. The centrality of music to the Scènes is all the more striking given that Rivette (like Rohmer) hardly ever uses extra-diegetic music – the haphazardly chosen but fittingly paranoiac Piazzola tango in the scene with the stone lions in Le Pont Du Nord being a notable exception – favoring the texture of direct sound or soundscapes highlighting the musique concrète of bird and traffic noises, of the squeaking floor boards and ticking clocks that remind us of Roland Barthes’ assertion – in Camera Lucida (1980) – that he can hear in the movie camera, that “clock for seeing,”the “living sound of the wood.” In a sense, the style of the trio in Noroît, a mix between the modern and the primitive, can be seen to have been rehearsed by the sparse percussion and dithyrambic chanting that accompanies the actors’ exercises in Out 1.

Querelle des anciens et des modernes

If these films are deeply embedded in the theatrical avant-garde of the period – not just Marc’O but Peter Brook and the Living Theatre of Julian Beck and Judith Malina, all based in Paris during the sixties – the plays at their center are classical to a fault: Shakespeare in Paris, Racine in L’amour fou, Aeschylus in Out 1 and Tourneur/Middleton’s Revenger’s Tragedy (performed in English and with act and scene numbers shown on title cards) in Noroît. Of the later films, Secret défense reworks Euripides’ Electra and Corneille’s Cinna, while Va savoir revamps Goldoni and Musset by way of their modern metatheatrical successor, Pirandello. Ancient Greek Dyonisian rituals were the source of both Artaud’s, Grotowski’s, Brook’s and Beck-Malina’s Nietzschian conception of a contemporary ritualistic, ecstatic theatre. But throughout his filmography Rivette has always mixed the Dyonisian with the Apollonian, as we will see.

In her excellent book on Rivette, Mary M. Wiles points out that the theatre company in Paris nous appartient was inspired by the Théâtre National Populaire, a theatre aimed primarily at reviving Greek and Elizabethan classics for a younger student audience. During the thirties and right after the War, popular dramatists like Jean Anouilh, Jean Giraudoux and Jean Cocteau had also managed to repopularize the classics. More generally, the relevance of classicism to Rivette as both filmmaker and critic at Cahiers has often been overlooked in the light of the epic jam session that is Out 1. But we should not forget that even that film’s spirit of free improvisation and jabberwocky – heralding a period of uncontained, proliferating signs and meanings – was still anchored in story and continuity, as we’ll discuss. Rivette was a lifelong admirer and connoisseur of the neoclassical tragedies of Corneille. And it is in the close adherence of Hawks’ films to the Corneillian ideal that we should look for the reason behind Rivette’s admiration for the classical filmmaker. As he writes in his famous essay on Hawks: “The father of Only Angels Have Wings and Red River is Corneille.” Like Corneille’s, Hawks’s art is one of “continuity, efficacy, functionality of action,” adhering to the Aristotelian unities that are central to the debate of Corneille’s famous Discourses (1660). Indeed, the dramaturgical problem, crucial to Corneille, of liaison des scènes, of how to connect one scene or situation to the next, has also been a central concern of Rivette’s. As in Corneille, Hawks’ stories are invariably about honor, passionate love, family loyalty, and how these qualities lead to moral dilemma and self-discovery (“Hawks’ genius is that he knows how to draw a moral”). Rivette discovered the same moralism in Lang or in Ray: “Nicholas Ray has always offered us the story of a moral dilemma where man emerges as either victor or vanquished, but ultimately lucid.” For sure, these are not the values one would associate with the revolution of youth. On the other hand, Corneille was a bit of a rebel himself, hovering between freedom and authority, writing the Discourses in part to appease the académiciens who had taken umbrage at the more free flowing form of his most popular play, El Cid (call it Corneille’s The Big Sleep) and thus anticipating the Quarrel of the Ancients and the Moderns. Academicians had also objected to the fusing of comedy and tragedy, which Rivette praised as a virtue in Hawks (“the one sharpens the other”) and loved in Renoir.

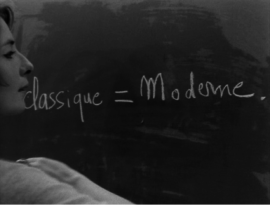

In the essay on Rossellini, Rivette attempts to unite modernism and classicism via the idea of simplicity, the celebration of the minimal gesture of truth, albeit one that can appear gauche (he refers to Cocteau’s coinage “superior clumsiness”). Rossellini is likened to Matisse not just because of his minimalist predilection for “large white surfaces,” or because of his “asymmetrism,” but for the preciseness of the single trait, which is also the painterly problem at the heart of La Belle Noiseuse. The ‘trait’ is not ‘beautiful’ in any academic way, but also not simply direct or ‘primitive’ in the sense of Cocteau’s clumsiness. The trait is clear, linear, stark and strict. It is in the absence of unnecessary embellishment and artifice, in the honesty of an art “stripped bare” that proceeds via the shortest, most efficient way to the essential (the pragmatism of Corneille), that classicism meets modernist minimalism. This is why the modernity of Hawks’ cinema is so “obvious,” the classical découpage of a guerilla-style Le Pont du Nord is not an oxymoron, and Godard was right to put that equation on the blackboard in Bande à part.

No Exit: Truth and Existence

Still, if we want to characterize Rivette’s cinema as dialectical, we should be precise about the Hegelian sense in which we mean this, not merely pointing to its reconciling seemingly opposite tendencies but to its close connection to history and culture. When Rivette became part of the entourage of André Bazin, most Parisian intellectuals, Bazin included, were in thrall to existentialism, if not that of Sartre, Beauvoir and Camus, then that of Christian existentialists like Gabriel Marcel, embracing this philosophy’s stance against conformity and for an authentic way of being in a senseless world. Sartre’s philosophy was popularized through his public appearances, his novels, his critical essays on popular American writers like Hemingway, Faulkner and Dos Passos, and through his work in the theatre. An existentialist theatre, for Sartre, was first of all a theatre of “situations”, a theatre of action instead of psychology characterized by an empty set, a reduced number of players and a telescoped, condensed playing time. The focus in Sartre’s theatre on a sparse style and on the life-determining choices occasioned by almost abstract situations returns it to a classical, Greek conception. Indeed, Sartre’s own plays were very often reinterpretations of myths or adaptations of classical tragedies. When Rivette writes about the sparseness of Hawks’ locations, or about the Hemingway-Faulknerian backbone of Hawks’ scenarios, he immediately brings to mind Sartrean dramaturgy: “It is actions that he films … we are not concerned with John Wayne’s thoughts as he walks towards Montgomery Clift at the end of Red River, or Bogart’s thoughts as he beats somebody up.” Another sentence focused on an action like, “Bogart escapes to the sea from the hotel which he prowls impotently, between the cellar and his room,” reads like a description of a Sartrean huis clos. Rivette’s summary of the typical Nicholas Ray plot approaches the theatre of situations even more: “Everything always proceeds from a simple situation where two or three people encounter some elementary and fundamental concepts of life.” Rossellini, Preminger and Ray are presented as the bitter, disenchanted, and even more boilerplate existentialist answer to Hawks-Corneille. In Rossellini the hero still ‘acts’ but now in a world devoid of God in which he is alone. In Ray he sees the same obsession with ‘twilight’, with the solitude of living creatures and the difficulty of human relationships. The action in Ray is always an existentialist struggle against “the interior demon of violence, or of a more secret sin, which seems linked to man and his solitude.”

Existentialism is also at the core of the Bazinian aesthetics to which Rivette, like Rohmer, always stayed true. The existentialists favored a representational art in which style is a matter of a coherent perspective or ‘Weltanshauung’ rather than the formal manipulations of modernist abstraction. This idea of a vision du monde expressed in a neutral prose style is what Roland Barthes celebrated in Camus in Écriture: degree zero (1953) – a source for Truffaut’s ‘Une certaine tendance’ (1954) in its exposing the conventionalism underlying French left-wing writing – and what Rivette would find in the neorealism of Rossellini: “It’s quite clear that Italian neo-realism wasn’t first and foremost a search for a style. It became a style; but it was part of a conception of the new world.” Similarly, existential phenomenology stressed an intentional way of being-in-the-world, that the world is always viewed from a certain angle. Rossellini’s eye, his ‘look,’ is “an incessant movement of seizure and pursuit which bestows on the images some indefinable quality at once of triumph and agitation” (in Godard’s words: with Rossellini a shot is beautiful because it is right). The intentional relationship between artist and world is mirrored by the one between perceiver and artwork: Bazin made a point of stressing the viewer’s share in a cinema based in reality, a “more active mental attitude on the part of the spectator and a more positive contribution on his part to the action in progress…it is from his attention and his will that the meaning of the image in part derives.” Given that the artwork should ideally express moral, ethical and political concerns, from the existentialist perspective the solicited participation on the viewer’s part is one of engagement. And it is here that the political side of Rivette’s cinema primarily resides, in producing an engagement that forces the viewer, as the existentialist liked to say, to “get her hands dirty” (see the quotation from Catholic existentialist Charles Péguy – who also provided the motto to Paris nous appartient: “Paris n’appartient à personne” – at the end of the Rossellini essay: “Kantism has unsullied hands, but it has no hands”).

The phenomenological core of Bazin’s aesthetics, the ‘Ontology’ essay, was equally influenced by existentialism. In his book on the psychology of imagination, L’Imaginaire (1940), a work known and cited by Bazin, Sartre writes that the imagination functions by the principle of the analogon, the image (a painting, a sketch, a photograph or even a mental image). Through the imaginary process the analogon comes to stand in for the object it represents and can take on new qualities based on the beholder’s intentions or feelings toward it: “The painting should then be conceived as a material thing visited from time to time by an unreal which is precisely the painted object,” Sartre writes. The ‘real’ object is thus always somewhere else, and the act of perception thus becomes one of seeing through the representational surface. By stressing the intention behind seeing, the capacity of the genius or ‘seer’ to uncover a purely cinematic truth by reaching through appearances, Rivette only brought out the Hegelianism in Sartre and Bazin. In his essays on Rossellini, Lang and Ray, Rivette stressed their revelation of the transcendental ideal – the idea and the concept of the world underneath its surface appearance: “Ray is lavish with ideas”; “Lang is the cineaste of the concept.” In La Belle Noiseuse, he showed us the dark side of this ambition: Frenhofer is haunted by the idea of capturing the essence behind the concrete physical individual, the whole of a life. But what if the portrait turns out to be mirror-like, like the one in Dorian Gray, or, indeed, “Life itself,” as in Poe’s “The Oval Portrait”? As Bazin discovered in the “Ontology” essay, the idea of representational form haunted by the ‘unreal’ of the real only becomes more pronounced when you’re dealing with a photographic art. Bazin summarizes the idealist-materialist dialectic behind cinema (which the late Gilberto Perez dubbed “The Material Ghost”) as a “hallucination that is also a fact.” Enter surrealism.

Through the Looking Glass

Before Marc’O was a theatre director, he was a surrealist and, later, a Lettrist, producing Isidore Isou’s infamous film Traité de bave et d’éternité (1951).He belonged to the intimate circle of André Breton and was a friend of Jean Cocteau, who together with Buñuel introduced Marc’O’s first film, the Joycean I-am-a-camera experiment Closed Vision at the 1954 Cannes film festival. Rivette has always stressed the importance of Cocteau to his thinking about the cinema and it is quite clear that the prominence of myth or legend, dreams and mirrors in Rivette’s films is something he shares with the maker of Orphée. Cocteau’s is undoubtedly the presiding spirit over the mythopoeic carnival of Duelle and Nôroit, with the former referencing both Chevaliers de la table ronde (1937), Cocteau’s unstaged mystical version of Arthurian romance, the ‘unholy’ sibling love affair from Les enfants terribles (1939), Cocteau’s dialogue for Bresson’s Les Dames du Bois de Boulogne (1945) and the noir netherworld of Orphée (1950). What is less clear is that surrealism was a constitutive element not only of Rivette’s films but of Cahiers aesthetics and the Nouvelle Vague in general. This blind spot can no doubt be explained by the fact that the two French film critics most strongly associated with the surrealist movement, Robert Benayoun and Raymond Borde, both wrote for the competition at Positif, a journal actively opposed to what they saw as the pious moralism of Cahiers. Also it is Left-Bank filmmakers like Resnais and Marker who have more closely been linked to the surrealist avant-garde, rather than the cinéfils of André Bazin: according to Adou Kyrou, Resnais never made anything without asking himself whether it would please André Breton. But in fact, as both Dudley Andrew and Christian Keathley have elucidated, Bazin himself was “a fanatic surrealist, a follower of Cocteau, and an energetic practitioner of automatic writing.” It was the practice and ideas of surrealism, its interest in automatism, in the blending of the imaginary and the real, and not necessarily its pictorial manifestations that interested Bazin, who praised Buñuel above other surrealists because “his surrealism is no more than a desire to reach the basis of reality.” In fact, key figures in French documentary film, like Jean Painlevé, Vigo and, especially, Jean Rouch were close to surrealism while there are surrealist elements in the documentaries of Marker, Resnais and Franju.

Like the surrealists, the Cahiers critics were fascinated as much by the symbolist poetry of Baudelaire, Mallarmé, Rimbaud, and Poe, as by popular culture, specifically with what was outmoded or had been discarded: Rivette and Godard shared with Breton and the Buñuel of L’Âge d’or and Un Chien Andalou a love for burlesque comedy in the Mack Sennett vein (as shown by Céline and Julie relentlessly mugging their way through the dénouement of their story). Even more than in comedy Rivette was interested in horror, adventure, crime and spy stories. A surrealist like Robert Desnos admired the larger-than-life characters featured in the movies and comic books in general, but the elegant thieves Fantômas and Irma Vep – whose descendants can be seen traipsing across the roofs of Paris in Paris nous appartient and Va savoir – in particular. Desnos wrote in the 1920s that watching films about their exploits was equivalent to dreaming, a suggestion Franju picked up for his version of another Feuillade serial, Judex (1963), which in turn inspired the break-in on rollerskates from Céline et Julie. Both Bazin and his acolytes were obsessed with Feuillade, the result of Henri Langlois’ tireless showing of Feuillade serials at the Cinémathèque (Langlois being, of course, another follower of Breton). Rivette has linked the ideal experience of sitting through the 13-hour version of Out 1 in one sitting to Langlois showing a Feuillade serial at the Cinémathèque, “starting at six in the evening and going on till one a.m. with three little breaks.” In his criticism, when he wrote ‘fetishistically’ about the “scarcely wrinkled hand in the penultimate shot” of Lang’s Beyond a Reasonable Doubt, or the “play between hand and object” in Preminger’s Angel Face, he is clearly working in the tradition of surrealist critics. Rivette’s films trade on the artistic technique of ostranenie, of making strange a familiar object or environment, as much as Feuillade or the photographs of a strikingly empty Paris by Brassaï that the surrealists liked so much. In his films a city becomes a labyrinth, a haunted Italian villa is situated directly off a large boulevard in view of the Eiffel Tower, an aquarium becomes the site of nightly criminal encounters (as in Lady from Shanghai), a next-door neighbor may well be involved in a worldwide conspiracy, and a dropped scarf and pair of glasses in a park become talismanic objects that initiate an incredible adventure.

Acéphale (or, Death to the Author!)

Rivette’s thematic interest in at least nine of his films in conspiracies, subterranean cabals, crime syndicates, blacklists, hidden plots and unexplained disappearances, derives from Feuillade and his two main successors, Lang and Hitchcock, but also from Balzac, Victor Hugo, the father of the roman feuilleton Eugène Sue and later sensationalist novelists, including the author of Fantômas, Marcel Allain, who was a surrealist. While Balzac was the great chronicler of the Bourbon Restoration and the July Monarchy, his disciples wrote about the criminal underworld of the Second and Third Republic, the street gangs led by shape-shifting master criminals, moulded after Balzac’s Vautrin, whose nickname ‘Trompe-la-mort’ (and suggested homosexuality) echoes in Jean-Pierre Kalfon’s mysterious Roquemaure in L’Amour par terre (the name also suggest the ‘rocambolesque,’ the French adjective deriving from another hero of the roman-feuilleton, Rocambole, and denoting the most fantastic of adventures). While Vautrin is a prince among thieves, the secret society of thirteen introduced by Balzac in Histoire des treize is an aristocratic cabal, a group of exceptional men of means and intellect who banded together under the Empire “faithful to a single purpose” (Balzac himself had tried to establish a secret society, ‘Le Cheval rouge’, composed mainly of literary celebrities). In Out 1 these men (and women) have become an elite but socially and demographically inclusive group of lawyers, architects, artists and intellectuals – including Cahiers co-founder and Rivette’s former boss Jacques Doniol-Valcroze – who seem to have disbanded after the end of the political turmoil of May ’68, just as Balzac’s thirteen parted ways after the death of Napoleon. In his preface to Histoire des treize, Balzac forges a link between his secret society and another initiatory organization, the ‘Compagnonnage‘. In Out 1 Renaud claims to belong to a secret organization called the ‘Compagnons du Devoir’, a masonic organization also mentioned in Bande des quatre. In their theatrical revue Le Trésor des Jésuites (1928), an hommage to cinema and Feuillade that was supposed to star Musidora but was never performed, Breton and Aragon included several references to masonic practice, including a final tableau in which the “Grand Orient Lodge of Paris” is revealed to be an extension of a sidewalk café, a precursor of the café-conspiracies of Out 1 and Paris nous appartient.

Several studies have pointed to Breton’s interest in the occult and the idea of the surrealist avant-garde as a kind of alchemistic secret society with its own initiatory rites and secret rituals. Rivette scholars Douglas Morrey and Alison Smith point specifically to the infamous but short-lived Collège de Sociologie (1937-39) founded by the former surrealists Georges Bataille and Michel Leiris together with sociologist Roger Callois, whose scholarly project it was to apply anthropological and ethnographical research methods to contemporary western society (exactly what Rivette is doing in Out 1), was preoccupied with the study of small groups, heretical sects, fraternities, monastic orders, terrorist organizations and so on. Even in his famous work on the sociology of games, Les Jeux et les hommes (1957), Callois stressed the hermetism of game worlds, characterizing them as “social groupings which tend to surround themselves with secrecy.” In the slipstream of the theoretical reflections of the Collège, Bataille founded his own secret society, Acéphale, a leaderless, communal group devoted to the celebration of ecstasy, which was equally short-lived because of the impossibility of performing the ritual sacrifice demanded by the chosen image of the headless monster: none of the members was prepared to lose his head!

All these societies – whether occult, ecstatic, or merely political – essentially have the same goal: to provide an alternative to the bourgeois order through the constitution of an elective community with an existential rationale instead of the rigid and constraining structures of the party or the bourgeois institution. It is in this sense that we should take Rivette’s comment that the conspiracy of the thirteen in Out 1 should not be seen as a sinister but as an utopian project. The communal watching of a 13-hour film in which the characters become like people you actually know, like friends, should also be considered in this sense, as the formation of an impromptu bande of friends. In a slightly different sense, both the idea of a group of cinephiles banding together to create a magazine and of young filmmakers joined together in a movement, a collective spirit also allegorized in Rivette’s many theatre troupes, also have something of the esoteric about it, if only because of the syllogistic logic behind a construct like auteurism that only makes sense to those in the know (“The evidence on the screen is the proof of Howard Hawks’ genius,” Rivette wrote about Monkey Business). Finally, there is the communal conception of the shoot itself, the family feeling so strong in admired filmmakers like Renoir and Bergman. Emulating the latter, Rivette has always tried to work with a regular stock company of players and technicians, like the incredible husband-and-wife pair of William and Nicole Lubtchansky, cinematographer and editor on most of his films, or the omnipresent Suzanne Schiffman, co-writer, production assistant and “assistante à la mise en scène,” perhaps his most important collaborator. Like Godard, Rivette has linked the strength of prewar American cinema precisely to the fact that talented people were working together all day under the studio system, “talking in the morning, in the cafeteria, and in a space other than a factory; it was a factory, but a very specific type of factory where they were able to talk”. All these groups are offered as alternatives to the kind of alienation and solitude that leads precisely to madness and obsession, to a delirious engagement with hidden messages. Jonathan Rosenbaum has suggested that the contrast between collectivity and solitude is perhaps Rivette’s main theme (here and here). Both are tied to a strong sense of place, whether it’s the womblike environment of the theatre or the rehearsal space on the one hand, or the seclusion of a nun’s cell, the lonely villa where a child is abandoned by her parents, the sparse apartments of L’Amour fou and Out 1, the gothic mansions in Merry-Go-Round, Secret défense and L’Histoire de Marie et Julien where poor little rich girls are searching for daddy. Le Pont Du Nord, Rivette’s only plein-air film, actually has the condition of homelessness as its subject, Marie and Baptiste finding security and comfort only with each other.

In several interviews Rivette has argued that after May ‘68 the revolutionary potential of cinema, if it exists at all, should start precisely with denying that a film is a personal creation, with the effacement of the auteur, a position familiar from Godard and Gorin’s Dziga Vertov Group (1968). This brings us, inevitably, to Roland Barthes and his essay on the ‘Death of the Author,’ published in ‘68 at the height of anti-establishment protest, decrying, in this case, a classical system of reading that makes the work as ‘consumable.’ For Barthes, killing off the author meant liberating the reader, removing all constraints on interpretation, stressing the autonomy of language, of the text. Rivette and Michel Delahaye interviewed Barthes for Cahiers in ’63, and at that time Barthes had already talked about a story’s capacity for a plurality of meaning. Cinema for Barthes (sounding at times like Bazin) seemed a potentially ideal text, open to a wide variety of independent interpretation given its special, metonymic nature, the slippery relation between its signifiers (that look like reality) and signified (reality). The mid-period Barthes of S/Z (1970) marked Rivette even more, and you could wonder to what extent this first exploration of ‘textuality,’ the text open on all sides to polysemy, influenced, in Out 1, both the rebellion against traditional fictional form and the intertext by Balzac. For the Barthes of S/Z a ‘text’ is a “tissue or fabric of quotations” drawn from “innumerable centers of culture.” Godard had reached the same Brechtian conclusion much earlier. In an interview with Cahiers late 1962 Godard had described his working method of feeding the actors pre-existing texts as ‘matter’ or piling up unattributed citations in a collage or bricolage that suggests an authorless text. Films like Duelle and Noroît that are almost entirely made up of citations are certainly the most radical applications of this principle, but the later films maintain the idea of a narrative woven out of already existing texts.

Among Barthes’ inspirations for pitching the author-less text in which language is given free play and a plurality of meaning is established, were Lacanian psychology, the poetry of Mallarmé and the surrealist experiments with chance and automatic writing. When Salvador Dali introduced his paranoid-critical method, his aim was precisely to produce an irrational knowledge based on a delirium of interpretation. The idea of “irrational enlargement” was also behind Breton’s habit of dropping in on the cinema, regardless of what was playing, on the look-out for the telling scene or moment, or Man Ray’s practice of watching the screen through his fingers to isolate parts of the image. This was post-structuralism avant-la-lettre but it also announced, as Christian Keathley has suggested, the Cahiers practice of watching differently, of conveying something of the uncanny nature of cinematic experience by scanning the film for telling details, a fetishism Barthes would later recuperate in his theory of the ‘punctum.’ In this sense, Colin’s (Jean-Pierre Léaud) obsessive rearrangement of the textual fragments of Balzac’s preface to Histoire des treize and Lewis Carroll’s The Hunting of the Snark in Out 1 can be seen as both an instance of textual deconstruction, surrealist game-playing and cinephiliac fetishism.

Petit bateau

Dali’s method was, in fact, an elaboration of Breton’s use in his novel Nadja (1928) – the supposedly true story of Breton’s accidental encounter with a young woman and the ten days they spent together in Paris in October 1926 – of anecdote and hallucinatory coincidence as structuring principles. Rivette always accepted the accidental, contingent elements of making a film, using accidents as much as improvisation, “letting in the messy things that give the impression that something is actually happening” (like all those kids and cats looking into the lens). The authorless and disjointed text full of incongruities and breaks (represented in Rivette’s films by pieces of black leader) came to be represented in the postmodernist novel precisely by contingency and its doubles, paranoia and the conspiracy without center, the plot in permanent state of suspension, as in the secret underground postal delivery service discovered by Oedipa Maas in Pynchon’s The Crying of Lot 49 (1965), Pynchon being perhaps the closest analogue for the Rivettian complot that turns out to be imaginary (or not). The Marxist critic Fredric Jameson sees the prominence of conspiracy theories in the cinema and literature of the late sixties and seventies as emblematic of the postmodern incapacity to represent a social totality. But you could also argue that in Rivette the paranoia produced by the suggestion of conspiracy, whether local or worldwide, is at once symptom of and potential remedy for societal malaise: it expresses the anxieties and conspiratorial nature of Cold War politics (Paris nous appartient), the defeat of social revolt (Out 1) or political corruption and social impasse coupled to personal dissociation (Pont du Nord), but it also creates endless possibilities for play, room for manoeuvre outside traditional hierarchies for both filmmakers, characters and audience.

Derrida famously labeled the result of the disappearance or ‘death’ of a central organizer ‘free play’ and Barthes similarly pitches the liberation of the signifier as leading to an endless and endlessly liberating series of associations, variations, dislocations, in other words to play in the mode of the surrealists. Breton seems to prefigure both post-structuralism and post-May Rivette when he writes the following: “When conversations about current events… began to lose its vigor, we were in the habit of turning to games.” In his 1958 bestseller, Les Jeux et les hommes, Roger Callois observed that one of the characteristics of play is the clear separation of the game world and the ‘real’ world. This idea of the community founded by the creation of a make-believe world, as well as the idea of playing games as a generative device, is perhaps best embodied by Céline et Julie, a film about the giddy freedom of invention and telling tall tales, with a distinctly neurotic undertone for sure, but still wild at heart. Juliet Berto characterized the shoot of the latter as “in the spirit of a kindergarten doing an end-of-year show for the grown-ups,” and the creative liberty of child’s play and make-believe has certainly intertwined in Rivette’s mind with the idea of playing/acting, especially when it comes to playing dress-up: watching Juliet Berto in Out 1, Céline et Julie and Duelle is like stumbling upon an old chest overflowing with magic-show props, dress jackets, nurses’ costumes and diva gowns straight out of an Amanda Lear video. In Pont du Nord, when Marie’s boyfriend Julien tells her to stop playing, to stop being childish and return the map she took from his briefcase, he is dressed like a movie gangster in a smart suit with a long overcoat and fedora. And we should not forget that one of Rivette’s first major critical pieces was a celebration of Hawks comedies in which adults behave like children.

There is a distinct Brechtian undertone here too, with the actors maintaining a fair amount of distance to the extremely fictional characters they are playing (leading precisely to those moments in which the actor overtakes the character). In an enlightening interview with Bernard Eisenschitz, Jean-André Fieschi and Eduardo de Gregorio following the release of Out 1, Rivette commented on the same Brechtian conception of play in the films of Jancso and Godard: “These are ten-year old children playing at spies or at war just like cops and robbers.” The “recreation time” Rivette observes in the Jancso films is not just about pleasure but about reinvention too: “the children are in the playground during break between classes, dividing up into groups, forming into rings, it’s the political game to the letter: politics as a game, a game as politics, Recreation time, but in the widest sense of the word; as Cocteau said, ‘When a child leaves the classroom, we say it is for re- creation.” So perhaps we should interpret Rivette’s retreat from filming the France of Giscard d’Estaing during the mid to late seventies, a retreat into fantasy shared by Rohmer and Resnais, not just as a confession of defeat but in the context of Breton’s comment about the lack of political ideas leading revolutionaries to turn to conceptual play.

Jeu de l’oie (Rules of the Game)

If Callois’ taxonomy of games posits paedia or children’s play as standing for unregulated, experimental free play, in all the other types a tension operates between predictability (the rules) and unpredictability. In the interview cited above, finding the right balance between premeditation and improvisation, chance and design is seen as the central problem in contemporary cinema (and music). A line by Benoît Régent in Bande des quatre could be taken as rephrasing the ‘problem’: “J’aime le hazard, mais j’aime l’ordre aussi.” Even Godard, in 1962, was still convinced that, for all the freedom and improvisation, you must have an overall plan to stick to that you can modify up to a certain point but that should change as little as possible once shooting begins. Otherwise “it’s catastrophic.” Discussing his ideas for Out 1 with Suzanne Schiffmann before shooting, Rivette decided on devising a temporal grid, the imposition on the story of an arbitrary number of calendar days (a device that would recur in the form of silent-film title cards in the films to follow). Talking about the difficult editing process of Out 1, Rivette said that he and editor Nicole Lubtchansky always had a strong sense of one scene necessarily following another, that it “didn’t cut together any old how.” This brings us back to the problem of Rivette’s classicism and the importance of Corneille’s “liaison des scènes.” Indeed, even the decision of having Out 1 (in its Noli me tangere version) start in documentary fashion as pure reportage, consciously withholding the incident that traditionally starts the narrative engine, can be seen as a novelistic device harking back to the long, purely descriptive passages setting up characters, settings and the social sphere in the novels of Balzac. And although the interview with Eisenschitz and Fieschi starts, predictably given the reign of the Nouvelle Critique, with a denunciation of the traditional idea of a central protagonist, even this most conventional structuring device Rivette was never willing to give up: despite the centrality of the collective at all levels of the plot, the story of Out 1 is still mainly told through the perspective of two outsider protagonists, Colin and Frédérique. In the films to follow, the single or dual protagonist structure is dominant, alternated only with the interlocking pairs of Lubitschian, Hawksian or Marivaudian farce, in which multiple couples join, separate and reorganize before bowing out in a collective tutti.

The return to structure and design brings us back to the Barthes of the 1963 interview whose less radical conception of narrative that cannot overcome certain constraints like sequentiality and temporal progression Rivette – despite his flirtage and experiments with a cinema of ‘pure signification’ – never really abandoned. The cinema, Barthes said then, is a discourse from which storytelling, anecdote, plot and suspense are never really absent. The new cinema that Barthes championed, in which meaning is ‘suspended,’ is not to be found in in the nouveau roman films that do away with plot and “mix chronology as a false assurance of modernity,” but rather in a film like Bunuel’s The Exterminating Angel (1962), a strictly linear film with a strong storyline, a clear beginning and end and an element of suspense (what Barthes would later refer to as the ‘hermeneutic code’: the enigma that moves the narrative forward). Similarly, when he conceived of Out 1, Rivette was looking less to films that had discarded plot in favor of pure psychology than to films that had doubled up on narrative, to films with parallel storylines like Vera Chytilova’s Something Different (1963), in which the marriage of a competition gymnast is contrasted to that of a housewife, or even André Cayatte’s La vie conjugale (1963), in which five situations are considered from the two different vantage points in the relationship (the model for The Disappearance of Eleanor Rigby and other he said/she said narratives). Rather than adhering to the binary contrast of these films, Rivette would attempt four parallel stories with eight interlocking character perspectives, looking for a breadth of coverage, a panorama or mosaic of Parisian life after May ’68 in the fashion of Balzac or Hugo. The central structure is that the episodes take the form of itineraries from one character to the next (from A to B, C to D etc.). The idea of a group of thirteen that aspire to world domination becomes the excuse to link up different storylines and character perspectives in an early instance of what David Bordwell has termed the “network narrative,” a fundamentally spatial, geographical conception of storytelling (“Network narratives suggest geometry or choreography, or boxes-and-arrows diagrams, or schematic circuits”; Rivette prefers the metaphor of the crossword puzzle) in which characters either familiar or only tangentially related, with shared or diverging purposes and projects, intersect or separate often through the sheer workings of chance, a dynamic emblematized in the hippie boutique cum bookstore and teahouse where Colin meets Pauline called “L’Angle du hazard.” The criss-crossing paths of these characters adhere just as much to the Situationist ‘dérive‘ or the surrealist conception of “magnetic fields” as to the picaresque narratives of Cervantes, Sterne and Diderot’s Jacques le fataliste. In this sense, Le Pont du Nord, a film that explicitly draws on all three, is at once the highpoint and the endpoint of this geometrical conception of narrative, a spatial fantasy that can be tied to a specific type of plot: the treasure hunt and its icon, the map, at the same time McGuffin and arbitrary objective or element of suspense and narrative grid.

For Le Pont du Nord, a story of a claustrophobic ex-con, Marie, and a paranoiac young woman, Baptiste, who accidentally meet in Paris and set out to solve the mystery of Marie’s ex-husband’s mysterious suitcase containing clues to a vast conspiracy spanning the crimes of the Giscard d’Estaing era, Rivette laid down a number of ground-rules or constraints which at first sight seem just as arbitrary as the principles of acting coach Constance Dumas (Bulle Ogier) in Bande des quatre: “Elle se donne des règles et au départ c’est complètement arbitraire”:

- do not use methods other than those of the so-called “reportage film,” as though surprise were paramount, and following the progress of our actresses easy, more or less (and so: never any artificial lighting, require the fiction to course through the streets, refuse it the refuge of any enclosed place;

- never leave the limits of the twenty arrondissements of Paris (and, in all likelihood, restrain the field of their wanderings even more than that);

- never let either of our two heroines out of sight (don’t leave their point of view: see everything, hear everything, encounter everything through them and across through).

Although these constraints, like the ploy of having Marie be a claustrophobic, were inspired by the film’s severe budgetary limitations, Rivette decided to use these strictures for another narrative exploration in which the idea of narrative as geography or cartography is heightened as never before. Among the papers in the mysterious suitcase is a map of Paris overlaid with a strange kind of Mabusian web that turns out to be a jeu de l’oie board. Paris nous appartient ended, more or less, on the image of wild geese taking flight over a pond, an image that critics have read as a typical postmodernist denial of fixed meaning, a synecdoche for the kind of semiotic paranoia that would lead directly to the post-structuralism of Barthes and Derrida. While you could also take the image as a variation on what Rivette called Rossellini’s “banal closing images that point to the cyclical nature of things” (“rivers flowing, crowds, shadows passing”), or as the emblem of a Shakespearian green world that fantastically or arbitrarily settles the problems of the city world, I think we should take it as a pun for the wild goose chase that Anne Goupil’s amateur detective embarks upon. (That Rivette, like Godard, delights in the silliness of such play on words is also shown in Noroît, when brother Shane ‘comes back’ from the dead, or in Céline et Julie when Céline talks to her friend about her stay with an imaginary American heiress: “Alice, c’est vraiment le pays des merveilles là!”). The jeu de l’oie idea in Pont Du Nord was probably borrowed from a novel by Jules Verne, Le Testament d’un excentrique (1899), in which the United States are seen as a Game of the Goose board with seven players from different parts of the country competing for an inheritance of sixty million dollars. The conceit also shows up in one of Raoul Ruiz’s first French films, Zig-Zag, le jeu de l’oie (une fiction didactique à propos de la cartographie) (1980), a short film made for television on the subject of cartography: a man (played by Pascal Bonitzer, the screenwriter-collaborator of most of Rivette’s later films) meets up with two strangers in the countryside who invite him to cast the die in a jeu de l’oie. The game will take the man, caught up in a “didactic nightmare,” throughout Paris and, finally, all over the world in which everything has become map, a reference to Lewis Carroll’s Sylvie and Bruno Concluded (1889). Ian Christie has likened the film to Chesterton but perhaps the more immediate point of reference is that great reader of Chesterton, Jorge-Luis Borges.

L’éternel retour

Ruiz does not consider himself to be a surrealist – although he is interested in spontaneous, unconscious processes of creation and shares with Robert Desnos (and the Rivette of Norôit) an interest in pirate stories – but he is most certainly a Borgesian, as can be judged by the labyrinthine nature of his ludic-philosophical stories. The history of Borges’ reception in France is another way into the architecture of Rivette’s work, like that of Borges’ friend and pupil Adolfo Bioy Casares, whose novel The Invention of Morel (1940), and its desert-island story of holograms eternally repeating actions and conversations, greatly influenced L’Année dernière à Marienbad (1961). Ruiz’s conceit of the country itself having become its own map in all likelihood travelled from Carroll (whose blank “Ocean-chart” from Hunting of the Snark it also echoes) via Borges’ “The Exactitude of Science.” That story was published in 1946 under the signature of B. Lynch Davis, a joint pseudonym for Borges and Bioy Casares. The ‘prologue’ Borges wrote for The Invention of Morel defended the form of the adventure story, standing in for a literature of anecdote, plot and suspense, against that of the ‘formless’ psychological novel that pretends to mimic reality. Taking off from Borges and Bioy Casares and predicting both Rivette and Ruiz, Barthes said in 1963 that, “even incredible adventures – anecdotes taken to the point of caricature – are not incompatible with good cinema.”

Borges was first introduced in France through the translations of Roger Callois, who had spent the War years in Argentina fighting fascism and whose booklet from the early days of the Collège, A Small Guide to the Fifteenth Arrondissement for the Use By Phantoms (1937) reads like a description of something out of Rivette:

The Paris that the reader knows is not the only, nor even the true city, but rather a brilliantly lit décor, all too normal…and which hides another Paris, the real Paris, a ghostly Paris, nocturnal, elusive, all the more powerful as it is the more secret, and which at every site and at every moment comes to mix itself dangerously with the other Paris.

Then there is Argentinian screenwriter and director Edouardo de Gregorio, another one-time student of Borges, who adapted ‘The Theme of the Traitor and the Hero’ for Bertolucci as The Spider’s Strategem (1970), and then went on to script the Scènes de la vie parallèle and Céline et Julie, into which he imported the holograms of The Invention of Morel decked out as characters out of Henry James. De Gregorio came to France in 1970 as part of a group of Argentinian exiles, including theatre producer Alfredo Arias, whose Parisian work includes adaptations of Marivaux, Goldoni, Balzac and James and whose blend of fantasy, magic, comedy and melancholy is also quite close to the Rivette of Céline et Julie. All of the films de Gregorio made either as a director or screenwriter showcase his interest in Fritz Lang and in the gothic novel, primarily the ghost stories of Henry James, whose The Other House and ‘A Romance of Certain Old clothes’ inspired the weird goings-on in the mansion 7 bis, rue du Nadir-aux-Pommes and all the haunted mansions to follow.

The Borges comparison has dogged Rivette just as much as it has de Gregorio. It was Suzanne Schiffmann who first turned him on to the Argentine master around the time of Paris and made him want to adapt ‘The Theme of the Traitor and the Hero’ (1944). The friendship and collaboration with de Gregorio then probably came about because of his professed admiration for Bertolucci’s adaptation. What fascinated Rivette above all was the final sentence in the story that adds another layer to an already vertiginous mise en abyme: a young scholar named Ryan writes a biography of his great-grandfather, the Irish revolutionary hero Fergus Kilpatrick, and discovers that his murder was stage-managed by his friend Nolan, who had discovered that the hero was a traitor and staged his execution as a murder for which he based himself on Julius Caesar and Macbeth. What Ryan discovers in the end is that Nolan had wanted him to find the parallels to Shakespeare in the hero’s death so as to learn that he was a traitor: “He understands that he too forms part of Nolan’s plot… After a series of tenacious hesitations, he resolves to keep his discovery silent. He publishes a book dedicated to the hero’s glory; this too, perhaps, was foreseen.” Ryan and Nolan are both authors of a fiction, but the first author figure is the storyteller introduced at the beginning in the framing story, idly imagining a plot under the influence of Chesterton and Leibniz. The story this author devises is one about truth and lies but perhaps primarily about the arbitrariness and open-endedness of fiction, offering up endless possibilities and forking paths. Ryan is disturbed by what he perceives to be the cyclical nature of Kilpatrick’s story, “seeming to combine events of remote regions, of remote ages.” It all seems to have happened before.

This cyclical pattern of repeated lines and coincidences – central also to Borges’ detective story ‘Death and the Compass’ (1942) and to The Invention of Morel (the story’s narrator mentions the “atrocious eternal return”) – is at the heart of Rivette’s narrative labyrinths. From Out 1 onwards, the idea begins to take hold of an unending, cyclical fiction with arbitrary endings (Rivette: “In the end I suddenly felt …that instead of leaving the story suspended, I wanted to pretend to end it, to make it (relatively speaking) a film with a conclusion”). As in the jeu de l’oie death is not final but just means that the player will have to start over. After Céline and Julie have escaped from the House of Fiction with Madlyn and decide to go on a boat ride on a placid lake out both Carroll and Renoir père et fils and they see the other figures of the House drifting by in another boat, they have embarked on another fiction. A cut takes them back to the very beginning, now with Céline on the park bench and Julie hurrying past. “Le plus souvent, ça commençait comme ça,” a title informs us at the beginning of the film, underlining the sense that all this has already happened many times before, a feeling critics have also ascribed to Rivette’s strangely sedate adaptations of fiercely passionate stories like Wuthering Heights (Hurlevent) and “La Duchesse de Langeais” (Ne touchez pas la hache). When L’Histoire de Marie et Julien ends back more or less where it started after a ritualistic tabula rasa, we are reminded that another Marie was invited to make the same gesture in Pont du Nord, the film that Daney described as a starting over, from square one, from a fictive and documentary Paris which had been the theater of Rivette’s début. In L’Amour par terre Emily remarks in Cocteauvian style on another House of Fiction: “Time is strange here – I have the impression of having been here forever.” L’Amour par terre is a story full of re-enactments – Emily and Charlotte are putting on a play in the mansion of the writer Roquemaure in which the story of his ménage à trois with Béatrice and Pierre is re-enacted and the actor playing him can be seen taking notes for turning the situation into a play – that ends with Emily and Charlotte leaving but ready to put on another spectacle, just as the characters assembling at the end of Va savoir are ready to start rehearsing the Goldoni play that served as MacGuffin in the movie. It is in these “boxes,” finally, that a balm is found for the sadness and melancholia at the end of Le Carrosse d’or, when Anna Magnani’s Camilla, alone on stage after the commedia has ended, is asked by stage manager Don Antonio: “Felipe, Ramon, the viceroy…disappeared. Now they are part of the audience. Do you miss them?” “A little,” is her sad reply. But don’t worry, as with fairy tales, there’s always another (re)telling. Nouveau départ, conquète!