An essay in two parts

2. Light on the Matter (or, Apples and Pears)

Lumière and Company

At the 2004 Cannes film festival, where he was presenting Notre musique, Jean-Luc Godard was asked about Kiarostami’s recent work with digital video. This is what he responded:

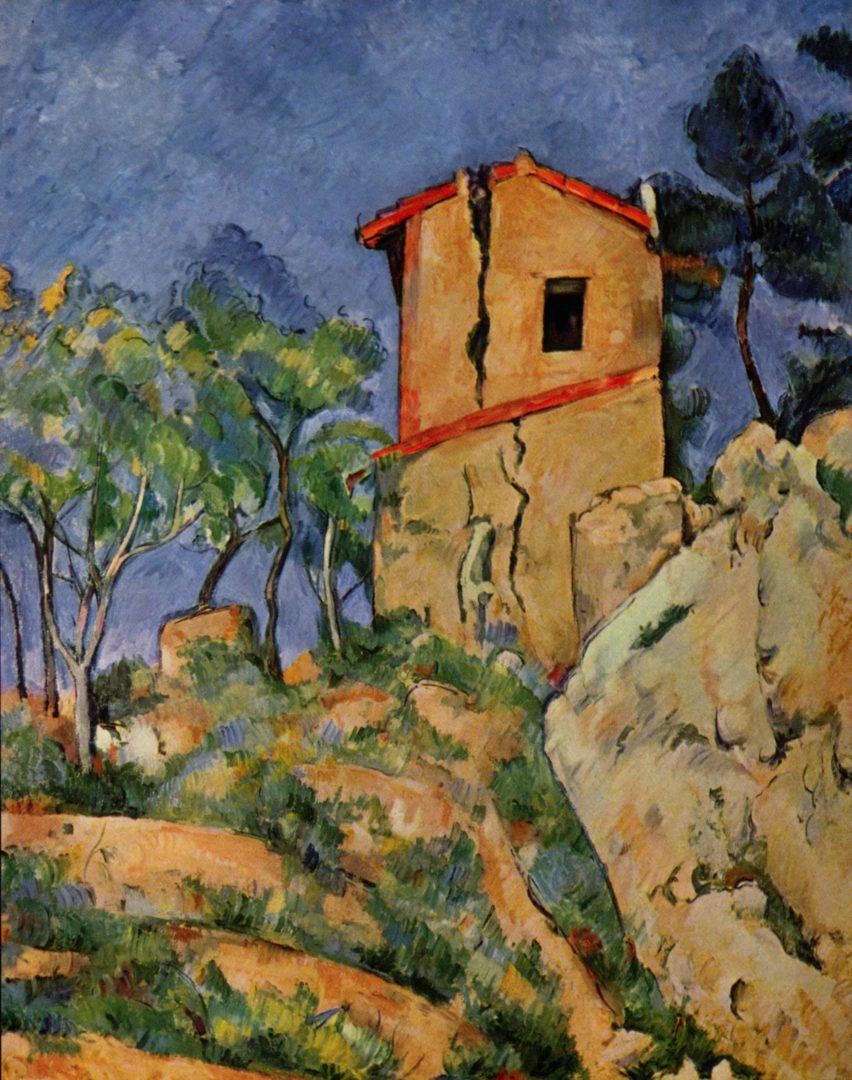

He made a magnificent film called And Life Goes On. Afterward he lost his way. And the West did not help him survive with lots of money or, rather, lots of glory. When you say this they say that you’re disparaging Kiarostami. Not at all. I’m not saying anything bad about him. I’m merely critiquing his films … It’s almost as if Kiarostami’s making films without a camera. If he were using the camera, he would not know what he was going to do — the camera would help him discover it. In the camera, the light is in front. In a projector, the light comes from behind. Whereas here, the light that is his intelligence comes before everything. It is not the light of the thing, like when Cézanne paints an apple or a glass. When Cézanne paints an apple, he’s not saying I am painting this apple. He says nothing. He paints it. Then afterward, when he’s showing it, he might say I painted an apple. So, now when I want to criticize a film I say, “It was made without a camera.”

The critique of Kiarostami summarizes a bunch of tropes high on the Godardian agenda in 2004 – light, projection, language – as we shall see, but fundamentally his criticism concerns agency and harks back to the teachings of Bazin: the filmmaker does not construct but the camera discovers. As is generally assumed, at the heart of Bazin’s discourse on cinema as automatism is the paradox of style, of the presence of the artist. In his 1952 essay on neorealism, Bazin’s correspondant, Catholic priest Amédée Ayfre wrote:

There is no doubt that film realism has its beginnings with Lumière, a man who never imagined his invention could be anything but an instrument for reproducing the real world. But from the outset, the mere fact that he positioned his camera in a particular spot, started or stopped filming at a particular moment and recorded the world in black and white on a flat surface was enough to establish an inevitable gap between the representation and the real.

Bazin himself agreed that “realism in art can only be achieved in one way – through artifice.” Concerning Lumière he added (in ‘The Life and Death of Superimposition’ from 1946) that “the opposition that some like to see between a cinema inclined toward the almost documentary representation of reality and a cinema inclined, through reliance on technique, toward escape from reality into fantasy and the world of dreams, is essentially forced.” The Bazinian question – an ontological deepening of the ethnographic problem of the observer’s paradox – has preoccupied Kiarostami from the very start of his career and has reappeared with renewed urgency after his discovery of digital cinematography. While the digital turn in cinema has been generally taken to disable Bazin’s conception of cinematic realism based on the indexal ability of the photographic image, for Kiarostami the introduction of the digital camera that has brought cinema closer to the ideal of transparency – the idea that we can literally see through the photographic image to reality – first formulated by Bazin: “For the first time, between the originating object and its reproduction there intervenes only the instrumentality of a nonliving agent. For the first time an image of the world is formed automatically, without the creative intervention of man.” In 10 on Ten (2004), a self-portrait that doubles as master class on the recent turn in his work (or vice versa), Kiarostami muses in very similar terms on the liberating potential of digital cinematography. Digital video footage first appeared in the infamous ending or postscript to Taste of Cherry, documentary ‘amateur’ footage of the crew taking a break from filming used in counterpoint to the film’s pessimistic ending. Kiarostami’s real turn to digital happened in his next film, the feature-length documentary ABC Africa (2001). Used as a sketchpad to record preparatory travel notes during a first location-scouting trip to Uganda, Kiarostami realized that the truth value of these spontaneously recorded images could not be bettered and decided to construct the film around them. Less intrusive in the environment in which it is introduced, if only because of the extremely reduced skeleton crew it allows (a principle also embraced by Éric Rohmer), the digital camera engenders more spontaneous, less inhibited reactions from the ‘actors.’ Because it can turn 360 degrees and imposes no limit on the length or staging of the shot, moreover, the digital camera is omnipresent, all-encompassing, and can thus report what Kiarostami calls an “absolute truth” devoid of artifice. When he elaborates that in his use of DV “mise en scène was spontaneously and unconsciously eliminated,” he sounds closer than ever to Bazin’s characterization of Bicycle Thieves as the first instance of ‘pure cinema’: “No more actors, no more story, no more sets, which is to say that in the perfect aesthetic illusion of reality there is no more cinema.” When he made 10 (2002) with two small video cameras attached to the dashboard, recording the conversations between a young woman photographer (Mania Akbari) and her passengers (her rebellious young son, her sister, a bride, a prostitute, a woman on her way to prayer), he not only reduced cinema to its barest minimum but seemingly eliminated his intervention as director, left only with the task of cutting together the automatically recorded ‘raw’ footage. This fact is underscored by his not putting his name on the film, preferring to remain nameless or hide behind a collective, as with the post-1968 Godard, or to take credit only for the ‘mise en scène’ (at heart no more than “a way of looking”, as Adrian Martin reminds us) as in Rivette. In fact, Kiarostami is more present than ever, sitting in the backseat in the blind spot between the two camera views, radioing dialogue to Akbari who wore a carefully concealed earpiece. The restrictive viewpoint of the locked down cameras also contradicts the idea of the omnipresence of an optic device with a potential circumference of 360 degrees. Off-screen space has never been so insistent.

Kiarostami’s digital turn has coincided with a preoccupation with the legacy of Lumière. In fact, his final film, a one-and-a-half minute short made for the Venice Film Festival compilation film, Venice 70: Future Reloaded, is a reworking of L’Arroseur arrosé in which the original’s mischief scenario gains in affective impact as the camera is turned on a young rascal behind the camera, reduced to giggles by this original instance of filmic situation comedy. Kiarostami was also working on a compilation project based on 24 four-and-a-half minute films, each a fixed tableau based on five paintings and nineteen photographs brought to life through the use of blue-screen technology, titled “24 Frames Before and After Lumière.” One of the films was based on Millet’s Les Glaneuses and ties the director’s interest in the aesthetics of Lumière to (proto-)Impressionist painting ( “I wanted to show what the painters heard and saw at the time but couldn’t express through their work,” he told an audience at a master class at the Marrakesh Film Festival). This connects him once again to the nouvelle vague’s own fixation on Lumière, specifically to Jean-Luc Godard, who in La Chinoise (1967) has Jean-Pierre Léaud’s Maoist student say, “Lumière was a painter. That’s to say, he filmed the same things painters were painting at that time, men like Picasso, Manet, or Renoir. He filmed train stations. He filmed public gardens, workers going home, men playing cards. He filmed trams.” The comparison between the nouvelle vague and Impressionism has since been overworked: like the Impressionists, the nouvelle vague cinéastes worked on the spot, ‘en plein air,’ with available light, producing sketch-like portraits of contemporary motifs that were seen as crude and amateurish, lacking finish and technical sophistication, accusations also lodged at one of their greatest precursors, Jean Renoir, the son of an Impressionist. Godard’s statement in La Chinoise must also be taken in the context of the director’s education at Langlois’ Cinémathèque (literally so since the Léaud character attributes his insight to “a film on Lumière by Monsieur Henri Langlois” he saw at the Cinémathèque; the film he is referring to, Louis Lumière (1967), was actually directed by Rohmer): the art lover Godard knew that Lumière père was trained as a portrait and landscape painter, but the cinephile Godard discovered that just as the motif of Lumière’s most famous film was borrowed from Monet’s La Gare Saint-Lazare series (1877), Cézanne’s Joueurs de Cartes (1893-96) inspired their Partie d’écarté (1896), which was shot in La Ciotat in Provence not far from Aix where the painter resided. On the other hand, by relating Lumière to Impressionism, Godard once again raised the fundamental Bazinian question of cinema as a medium of both (mechanical) registration and poetic expression, recalling Mallarmé’s definition of Impressionism as a direct form of registration that has forgotten “all acquired secrets of manipulation”: “The eye should forget all it has seen, and learn anew from the lesson before it…that which it looks upon as if for the first time.” The ability to “see nature and reproduce her, such as she appears to just and pure eyes” is what defines a movement Mallarmé equates with “the search after truth, peculiar to modern artists.”

That Godard would think of Cézanne, makes sense given that the latter has remained an important point of reference for the filmmakers associated with the nouvelle vague: Rohmer’s is only the most explicitly Cézannian use of modulated color, but the transparent effect of Cézanne’s watercolors also shows up in Godard’s video work. Rohmer, who, like Godard, often worked in Cézanne-like planes and at one point defined his work in elementary terms as, “Nature: water, rain, snow, cherry trees, fruit, flowers,” has set many of his films in locations where Cézanne painted some of his most beautiful work: the lake of Annecy in Le Genou de Claire (1970), Cergy Pontoise in L’ami de mon amie (1987), Aix-en-Provence in La collectionneuse (1967). Godard was probably also brought in mind of Cézanne because of Straub-Huillet’s Visite au Louvre (2004) released the same year as 10 on Ten. Visite au Louvre was made as a companion piece to the Straubs’ Cézanne Conversations avec Joachim Gasquet (1989). Both were based on Gasquet’s Cézanne (1921), a book that records the art critic’s conversations with his friend the painter (the Cézanne quotations in my text are all taken from the film). It’s interesting to note that Straub-Huillet – whose cinema bears comparison to Kiarostami’s both in its careful work with non-professional actors, the extreme precision of the cutting and the preference for the panoramic panning shot in the manner of the Lumière travelogues – were first incited to look deeper into Cézanne by Rivette, who had recognized the painter’s stamp in the view of Florence from the surrounding hills in their Fortini/Cani (1976). Generally, it can be said that Cézanne embodies the meeting of realism or naturalism and modernism, the latter taken in the sense of the artist reflecting on the medium’s essential properties, that characterizes the nouvelle vague. In Kiarostami also there is a strong affinity to Cézanne that goes beyond the preference for earthy tones with splashes of bright color, the borrowing of pictorial motifs and the prominence of olive trees in both Provence and Rudbār.

Partly because of Derrida, Cézanne’s enigmatic statement to another art critic friend, Émile Bernard, in a letter from 1905, has become a defining quotation (“a characteristic trait” according to Derrida): “I owe you the truth in painting and I shall give it to you.” Bernard confirmed that for Cézanne the conception of beauty was secondary; he possessed only the idea of truth. It’s unlikely that Kiarostami was thinking of Cézanne when in the Bomb interview with Akram Zataari he credited his son (and later editor) Ahmad with the insight that “if we analyze different aspects of the lie, then we can arrive at the truth.” But he could have been thinking of a similar slogan by Cézanne’s most important disciple, Picasso, who said that “Art is a lie that makes us realize truth” (the capital A is Picasso’s). The quote comes from a 1923 interview with Mexican artist and gallery owner Marius de Zayas on the subject of the Cubist revolution in art. Picasso argues in the interview that the truth in art has nothing to do with mimesis. Since art and nature are two completely different things (“Through Art we express our conception of what nature is not”), naturalism is as conventional as abstract art. Both are lies and the question of truth pertains only to which of the two is the most convincing form for the subject at hand (“the artist must know how to convince others of the truthfulness of his lies”). The truth for a modern artist like Picasso lies in “keeping within the limits and limitations of painting, never pretending to go beyond it.” For Picasso, the truth is truly in painting, beauty in the very means of painting itself. It’s instructive to consider the possibility that Picasso’s slogan was in turn inspired by one of his great inspirations, Edgar Degas, author of another famous claim: “Art is the same word as artifice, that is to say, something deceitful. It must succeed in giving the impression of nature by false means, but it has to look true.” In Degas’ opinion the ‘directness’ of Impressionism celebrated by Mallarmé, however, was far from incompatible with technique. On the contrary, as the art historian Ernst Gombrich writes, “the new principles embraced by these young artists were posing new problems, which only the most consummate master of design could solve.” Degas confirms: “I assure you that no art was ever less spontaneous than mine. What I do is the result of reflection and the study of the great masters.” Similarly, Manet came to reach his level of directness only through study of the masters, in his case Vélazquez and the Flemish Masters. And along parallel lines, Gilberto Perez recognizes in Impressionism a dialectic between formalism and realism that he finds typifies the modernist art of Kiarostami and Straub-Huillet:

The emphasis on the means stems from the difficulty in achieving the end. An art that dissembles its means wants us to accept the perfect adequacy of its access to the truth; an art that calls attention to its means wants us to recognize it as a construction, a matter of choice rather than necessity, an order of human making rather than a higher order of things. A higher order would supply the answers; an order of human making must put things in question, put itself in question. Modern art declares its means not because they are its only subject but in order to put them in question, because it feels it cannot take its assumptions for granted in its search after truth.

In 10 (2002), a film that for casual viewers looks like Taxicab Confessions, the editing choices are as stringent and visible as in the ‘analogue’ films, whether they’re based on classical continuity rules of shot-reverse shot or, as in the opening scene, involve the Godardian tactic of withholding the reverse shot. Even Kiarostami’s most experimental work for the cinema (that doubled as an art installation), Five (dedicated to Ozu) (2003), a DV recording of five distantly framed static shots of sky and water with only the slightest human or animal incursion, which Kiarostami has described in distinctly Warholian (or Mallarméan) terms as representing a process in which “the author disappears,” shows through its dedication to Ozu, arguably the most insistently ‘present’ director in all of cinema, that the dice are loaded. As Jonathan Romney has remarked, not only is the director clearly present in handling the DV camera in the first episode, he is also making editorial choices about the length of each vignette, lens and aperture setting, scoring and the compositing of material from various sources (as in the last episode, showing a moonlit pond before, during and after a storm in a time-lapse montage). In his essay, ‘Cézanne’s Doubt’ (1945), French philosopher Maurice Merleau-Ponty points out that it took the painter one hundred working sessions for a still life, one hundred- fifty sittings for a portrait. This is fanaticism, for sure, but it is also dedication. Bernard defines ‘beauty’ in Cézanne accordingly as “the fullest development of the art employed.” In his conversations with Gasquet, Cézanne compares the work of Tintoretto and Veronese, true geniuses and artisans, to the ‘messiness’ of his contemporaries:

Nowadays they build up the paint right away, they go into action crudely like a bricklayer, and they believe that makes them stronger, more honest . . . what rubbish. We’ve lost this knowledge of preparations, this freedom and vigor gained from the underpainting. To model – no, to modulate. We need to modulate… Look what gets done today! Retouching, scraping down, rescraping, laying on thick paint. It’s like using mortar.

Kiarostami took eight months editing ABC Africa, which was then dismissed as ‘artless.’ He spent months working on the soundtrack of The Wind Will Carry Us (1999) alone, which most viewers then dismiss as merely ‘natural background sounds.’ Again, a comparison is in order to Straub-Huillet who prepare rigorously for each film, then, like Bresson, subject their actors (sometimes themselves) to endless line readings during the shoot, subtly modulating between different incarnations, to make films that are taken at first glance to be mere recordings of plays, musical performances or paintings.

Solid Shape

In her recent Cinema Scope piece on Perceval le Gaullois, Andréa Picard quotes Eric Rohmer on Cézanne: “What gives truth to a Cézanne is not the pseudo-likeness to the model, it’s the trace it carries within it of the process by which the painter perceives it.” This can be read in an idealist way that would indeed fit early and mid-career Cézanne, who famously said, “The landscape thinks itself in me and I am its consciousness.” Indeed, the definition of Impressionism around 1890 was closer to the characterizing traits of Symbolism – the evocation of immaterial ‘Ideas’ through a purified style – than to objective registration. Merleau-Ponty has something more corporeal in mind when he writes that “Cézanne was able to revive the classical definition of art: man added to nature.” This is again a quotation, from Van Gogh this time (in one of his letters to his brother Theo), a painter who was highly influenced by Cézanne (Van Gogh’s Wheatfield with Crows from 1890 is a leading visual motif in Taste of Cherry). In Van Gogh and Cézanne, Symbolism, defined by Jean Moréas in his manifesto of 1886 as the art that gives sensual form to the ‘Idea’ (as in Cézanne’s assessment of Veronese: “That to me is Veronese: the fullness of idea in color”) meets another form of encounter with the world, which the German philosopher Edmund Husserl termed ‘phenomenology.’ Phenomenology, in its most basic definition, is less a system or methodology than an incentive to describe phenomena as they manifest themselves in consciousness. Merleau-Ponty’s existentialist brand of phenomenology posits that this activity of description can only take place, not from some abstracted point of view, but from your own position in the world you are describing. Moreover, this ‘consciousness in the world’ is inevitably embodied since the subject that ‘I’ am is inseparable from my body. Cézanne compared his talent for capturing a moment in time to the working of a sensitive plate or recording machine. As the art critic Jonathan Crary writes in his book Suspensions of Perception: Attention, Spectacle and Modern Culture (2000), the recording device that Cézanne used was his body: “After spending hours and hours in the countryside, the painter would return to his studio. There, he was so filled with a sort of corporeal resonance from the sun, the leaves, the grass, the water, and the trees, that his hand alone could automatically paint what he had felt and stored through his body by underplaying the analytical side of perception.” So when Cézanne defines art as “a personal apperception, which I embody in sensations,” he sounds like the kind of phenomenologist Merleau-Ponty would like.

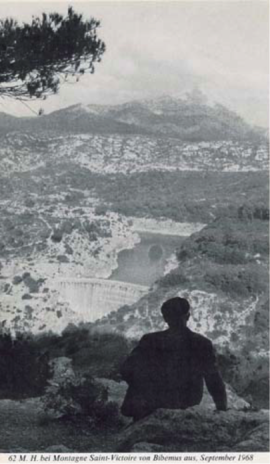

Merleau-Ponty’s existentialist phenomenology was shared by Ayfre and, from the other side of the political spectrum, Sartre. Both had an important influence on Bazin, which might help explain the centrality of Cézanne to the discourse of ‘Bazin’s children’ in the New Wave. For Merleau-Ponty, what Cézanne does is convey a “lived perspective” on the phenomena, which frequently appear to us as a jumble of disconnected forms, or in a warbled way as, for example, in the illusion we have when we move our heads that objects themselves are moving (hence the bizarrely warped perspective of Cézanne’s sloping and tilting objects in the still-lives). This might still qualify as the kind of perceptual impression the Impressionists were trying to capture, but what Cézanne was after was something more solid than an ‘impression,’ a momentary ‘atmosphere’ made out of light and air. When he said that he wanted to make “something solid and enduring” out of Impressionism, he meant this in a double way. The first implies a return to the artisanal qualities of painting, to the grandeur, serenity and unity of the Venetian masters, or of Poussin, rather than the fragmentary views and rapid strokes, the ‘snapshots’ of the Impressionists. “Something solid” meant “solid like the art in the museums,” a reference to his disappointment in the failure of Impressionism to produce an actual masterpiece fit to stand next to the masterpieces of Tintoretto or Delacroix. He also meant that he wanted to depict an “essence.” The essence he has in mind is not the universal typology or unchanging aspect of experienced reality of Husserl’s ‘transcendental’ phenomenology, but a core of materiality: light in Cézanne is not reflected but comes from within objects; “light emanates from them,” as Merleau-Ponty describes it. The result is an impression of essential qualities of solidity and material substance. D.H. Lawrence, another admirer, though a Vitalist, in his essay on Cézanne also starts by pointing out the painter’s anti-idealist qualities when he writes that “Cézanne’s apple is a great deal, more than Plato’s Idea: in Cézanne modern French art made its first tiny step back to real substance, to objective substance, if we may call it so. Van Gogh’s earth was still subjective earth, himself projected into the earth. But Cézanne’s apples are a real attempt to let the apple exist in its own separate entity, without transfusing it with personal emotion. He is willing to admit that matter actually exists.” Gilberto Perez notices a similar quality in the sunflowers, apples and pears of Dovzhenko’s Earth (1930). “His images seldom gives us an elusive impression, the passing glimpse, the oblique view; things, squarely confronted, show us their full face, so to speak, and are held on the screen long enough for our eyes to go beyond the mere appearance and get a grasp of the substance.” Perez likens this corporeality to Giotto and his successors in the Italian and Northern Renaissance – Cézanne’s confessed masters – who also rendered the fullness and self-sufficiency, the rounded steadfastness of solid forms. The solidity of form is also what preoccupies Kiarostami and one of the reasons why he dislikes tracking shots. During the shooting of The Wind Will Carry Us he rejected a travelling shot suggested by the camera crew to capture the engineer and his young guide walking through a forest, because it creates the phantasmagorical impression of the forest starting to move, of trees parading through the shot. Kiarostami prefers a simple pan, not just out of an ethos of economy and simplification, but because it looks more real from a perceptional point of view, stressing both the harmony between the two living beings and the rootedness of the trees in the ground. Still, Cézanne’s ‘solidity’ is no mere materialism, as Merleau-Ponty elucidates: “Cézanne wanted to depict matter as it takes on form, the birth of order through spontaneous organization, to create the impression of an emerging order, an object in the act of appearing, organizing itself before our eyes.” Order is not imposed on matter, as in the idealist tradition; it organizes itself as it appears to our perception. Nature is not copied, but realizes itself in the artwork. Starting from a derealization, the work confronting us as entirely abstract and two-dimensional, objects and forms then reconstitute themselves and reappear, a process Cézanne himself called “realization”. As Merleau-Ponty writes about the painter’s endless variations on Mont Saint-Victoire: “The mountain makes itself mountain before our eyes.”

Merleau-Ponty here shows the rootedness of French phenomenology in the work of another German, Martin Heidegger, who was much devoted to Cézanne, especially to his gift for revealing to us the invisible horizons of perception that everyday perception takes for granted, for rendering the invisible visible. The philosopher visited the painter’s home and was overwhelmed: “These days in Cézanne’s home are worth more than a whole library of philosophical books. If only one could think as directly as Cézanne painted.” This is no idle wish as those versed in Heidegger will testify to the often bewildering doublespeak, neologisms and poetic digressions with which the philosopher tried to capture the most primordial given of all, being, or rather, Being (which Heidegger, to stress how existence is bound up with the world, calls Dasein). Heidegger would rephrase Merleau-Ponty’s meaning of nature ‘realizing’ itself as the “world worlding,” the world ‘unconcealing’ itself in the artwork. ‘Unconcealment,’ disclosure, is a crucial term in late-period Heidegger and is central to his aesthetic philosophy as laid out in ‘The Origin of the Work of Art,’ a text drafted between 1935-37 then reworked in 1950. For Heidegger, the work of art is not about subjective pleasure or enjoyment. Neither is it mimesis, the representation of some-thing ‘to hand,’ but the realizing of the Being of things. So when he discusses the example of Van Gogh’s A Pair of Shoes (1886), he argues that the art does not reside in the artist’s skillful talent to reproduce an object in reality, in its representational correctness, or in the fact that the shoes are beautiful in the way they were painted, but in the fact that the shoes are disclosed in their essential being, in their truth. The truth of the work is that is reveals the shoes as being part of a world, an agrarian world that is threatened by extinction in our modern machine-like world. Indeed, Heidegger’s aesthetics belong with his work on technology (‘The Question Concerning Technology’ 1954) to a tendency denouncing the increasing rationalism and instrumentalism of the technological/scientific world. This instrumentalism has blinded us to Being. It is only when things fail – when a hammer falls apart when hammering, to use Heidegger’s favorite example – that we become aware again, not only of the hammer’s objecthood but of the world as a whole in a whole new way. The failure of the habitual is what art enacts; for Heidegger art had the great potential to counter technological or functionalist ‘enframing’ and disclose the person (or object) for what he (it) really, distinctively is, his (its) true being. Together with Marx, Freud and Brecht, Heidegger is modernity’s great thinker of ‘estrangement.’ The function of estrangement is to make you see again, to defamiliarize what has become routinized, pragmatic, deadened. In his famous text, ‘Art as Technique’ (1917), Russian formalist Viktor Shklovsky posits that arts exists precisely to make one recover the sensation of life, to re-enchant life, in a world that has become habitual and automatic; it exists to make one feel things, “to make the stone stony” again, as if it were something new that requires a long, hard look. In similar terms, Bazin described the working of photography: “Only the impassive lens, stripping its object of all those ways of seeing it, those piled up preconceptions, that spiritual dust and grime with which my eyes have covered it, is able to present it in all its virginal purity to my attention and consequently to my love.” This is exactly what Cézanne did in his still lifes: making the pear ‘pearey’ again, the apple all ‘appley,’ turning them into a ‘new natural’ by discovering their primordial form and teaching us not only how to see again, teaching us what seeing is, but what an apple is, drawing us out of ourselves into ‘appleyness’ as if we had never experienced apples before. In The Wind Will Carry Us an apple falls down a balcony into the boy’s hands, ‘meandering’, not falling in a straight line, but suggesting the essence of movement as grounded in obstruction. Like Cézanne, Kiarostami shows what an apple is. As a filmmaker, he also shows what movement is.

When we say that the artist ‘shows,’ has managed to make us see again, we exaggerate the artist’s agency, who in Heidegger is more like a medium through which unconcealment happens. What is at work in the work is not the artist; at the most the artist’s world is at work through the artist. (This logic predetermines why Heidegger – like Hegel – thought art was a thing of the past: while in classical antiquity art was an essential mode in which the truth happens for a historical Dasein, in other words had a clear communal and world-historical function, this is no longer the case in modernity; Heidegger will recant this position in his late work, precisely because of his encounter with Cézanne.) This brings us back to Godard’s critique of Kiarostami. When Godard says that Kiarostami is making films without a camera, he implies that the filmmaker is projecting and not recording, not discovering. Godard thinks about Cézanne in the same way he thinks about Manet in Histoire(s) du cinema (1988-98), as a painter who thinks forms and at the same time paints forms that think. Godard, of course, has a personal stake in the matter, given that his late work has been primarily about recovering the essence of cinema as thinking form, of the ‘cinematographic’ (Bresson’s term) over the filmic, which is just another word for incident and story. Godard’s greatest enemy is the cerebral, the rational and the instrumental encapsulated in the everyday conception of language as conveyor of information. The ideal is to know things more directly, materially, essentially, before their ‘enframing,’ before conceptions or propositions. (In L’enfance de l’art (1988) this anti-foundationalist stance is given an ideological bent: postcards showing Delacroix’s La Liberté guidant le peuple (1830) spell out: “De toutes les tyrannies la plus terrible est celle des idées.”) “When Cézanne paints an apple, he’s not saying I am painting this apple. He says nothing.” The muteness of Cézanne returns us to Lumière where ‘an apple’ is not exploited for narrative purposes, not labeled or named, but simply shown for our enjoyment and contemplation (as in the film John Grierson remembers of “the Lumière boy eating an apple”).

There is also the sense, in Godard’s comment that “the West did not help him survive,” not only of ‘too much money’ (as Rivette wrote about Preminger, “wealth dulls sensibility”), but of a filmmaker starting to believe his own (Western) press. It is certainly disquieting to hear a filmmaker Perez describes as “the most unaffected and uncomplicated” discourse on Deleuze on the subject of his last two feature films, Certified Copy (2010) and Like Someone in Love (2012)Like in this interview with Filmmaker magazine.. For all their qualities, these late films indeed seem far removed, historically, geographically and esthetically, from the world of Life and Nothing More. Their reflections on original and copy, essence and appearance, do read at times like illustrations of Deleuze’s idea of the ‘simulacrum.’ It is also striking that these films entertain an explicit dialogue with the problems and discourses of the contemporary art world: Certified Copy was released in the same year that MOMA produced an exhibition on the photography of sculpture entitled The Original Copy; two years earlier the Tate Modern had organized a conference on “The Replica and Its Implications in Modern Sculpture.” Like Someone in Love similarly relates the question of reproducibility to roles and role-playing and takes the idea of the replica to Tokyo, city of the Baudrillardian hyperreal. Godard, who for all his importance to the contemporary art world, has always refused such dialogue and hardly ever quotes from contemporary ‘post-aesthetic’ artistic practices (in The Old Place (1999), a film commissioned by MOMA, Godard and Miéville reject abstract art as the work of artists who can no longer affect history), probably took exception. Somewhat surprisingly for a filmmaker who in his early and middle period was much indebted to Structuralism and OulipoOulipo is a loose gathering of (mainly) French-speaking writers and mathematicians who seek to create works using constrained writing techniques.-like procedures and constraints, Godard’s biggest problem seems to be with Kiarostami’s conceptualism. In the language of Cézanne this means “tracing a single outline to capture a multiform reality.” What Godard takes from Cézanne is the opposite idea of painting/cinema as a means of discovery, an art denuded of any preconceived notions or schemas. In Visite au Louvre Cézanne is quoted railing against the academicism of a painter like Ingrès: “By setting out to paint the ideal virgin, he hasn’t painted a body at all . . . because of the idea of a system. False system and false idea.” The logic harks back to Michelangelo: to create means not to add or shape, but to take away, to reveal, like the sculptor revealing the sculpture that already exists inside the block of marble. This is the logic cited by Rivette both in his review of The Lusty Men (1953) and in his famous ‘Letter on Rossellini’ (1955), Rivette who, in fact, anticipates (as so often) Godard’s comment by his unenthusiastic response to Taste of Cherry in 1997: “His work is always very beautiful but the pleasure of discovery is now over.” Rivette had celebrated the directness and ‘naïveté’ in Rossellini and in kindred American spirits like Aldrich and Ray because they provided a gust of fresh air in a cinema ‘dying’, precisely, ‘of intelligence’. So what Godard bemoans is that Kiarostami has ceased to be like Rossellini, ironic given that Certified Copy is explicitly about its relation to Viaggio in Italia.

Boîte-regard

The most widely cited text on Kiarostami is by French philosopher Jean-Luc Nancy, The Evidence of Film (2001). When he was invited by Cahiers du Cinéma in 1994 to write about a film of his choice to celebrate the hundredth anniversary of cinema, Nancy picked Life and Nothing More. At the time Kiarostami had gained some recognition from Where is the Friend’s Home but was not yet the celebrated international auteur who would go on to win the Palme d’or for Taste of Cherry. The reason Nancy gives for choosing to write about this particular film is then that, “to avoid nostalgia”, he wanted to pick a recent film, and that the film’s ‘evidence’ imposed itself on him. The evidence of this choice probably imposed itself also because Godard’s definitive statement on Life and Nothing More, “The cinema starts with Griffith and ends with Kiarostami,” had made it explicitly a choice about (film) history, about beginning and ending, life and death. When Nancy writes that the film had “impressed itself on me in an obvious way,” what imposes itself, however, is the evidence of the film’s insistence on the present. Godard famously distinguished between the time of the novel – a past tense, relating something that has already happened – and the time of reportage, with which he associates with (his) cinema. Cinema feels like something happening in the now because it shows a (historical) world coming into being. But for Nancy the present-ness of Life and Nothing More engenders something else besides immediacy, something that is immediately related to the context in which the essay originated, the celebration of cinema’s history. Nancy’s variation on the ‘end of art/history’ rhetoric is that, with Kiarostami, cinema begins again, yet loaded with one hundred years of its history; it is its continuity that keeps giving it a fresh start, “the affirmation of cinema by cinema.” Late Godard assumes a similar position: we need to begin again, go back to the beginning, like Cézanne or Heidegger, and paint/think/make films as if no painting/thinking/cinema had been done, while at the same time having dialectically preserved everything that has been done. Nancy also sounds thoroughly Heideggerian when he says that Kiarostami is “a witness to cinema renewing itself,” coming close again to what it is, or that this “essence” of cinema is expressed “through” him.

‘Evidence’ is the structuring play-on-words in the text – next to the different meanings of the French ‘regard’ as ‘look’, ‘inspection’, ‘consideration’ and ‘respect’ – that grounds it in Heideggerian/Derridean attention to language, specifically etymology. Nancy links the common usage of ‘evidence’ as ‘proof’ (of the truth of a proposition) and the phenomenological sense of ‘self-evidence’ – the lived moment of consciousness – to a more specular sense contained both in the Latin root evidens (an adjective meaning ‘evident’ in the sense of ‘visible’, ‘clear’, ‘plain to see’) and the verb videre (‘to see’). Essentially ‘evidence’ denotes ‘that what is clearly be seen to be true’. Fittingly, the Greek root of Heidegger’s ‘unconcealment,’ alêtheia, denotes ‘the state of not being hidden; the state of being evident,’ where ‘evidence’ points to a pre-philosophical, pre-conceptual sense of understanding the world. For Husserl, the term ‘evidence’ occasions both a return to the things themselves and a form of intentionality, a ‘being directed towards something.’ Nancy combines both conceptions of ‘evidence’: as intentionality and as becoming evident, as truth ‘realizing’ itself. Kiarostami’s cinema is about images that open onto what is real and about the look that ‘carries’ (a pun on The Wind Will Carry Us). Nancy uses the common and specialized sense of ‘evidence’ interchangeably when he says that the film tells us to look, to learn to use our eyes again. To give again the real, to realize it, is genuinely to look at it. Kiarostami’s films are literally ‘eye-openers,’ provide an ‘education’ (Kiarostami’s pedagogical project) in looking at the world. An example of such eye-opening moments Nancy finds in our earlier example, the ending of Close-Up: “as ‘cinema’ (sound, focus, editing) fades away, the blooming flowers bring to mind what is verily cinematic.” As this scene shows and Kiarostami’s subsequent ‘road’ movies confirm, what is cinematic is not only what can be seen but also what moves in time, what is literally kinematic. For Heidegger living and understanding implies a form of anticipation, of projecting yourself forwards from a rough practical knowledge (a ‘pre-understanding’) of what the world is. Heidegger calls this forward motion ‘Entwerfen’: while always bound by my existential situation (the past, the world in which I find myself), I am never purely identical with myself but always thrown forward in advance of myself. Insofar as Dasein anticipates, it comes towards itself. Nancy sees the car in Kiarostami’s films in these terms: the car is a box that looks and an incessant movement; it looks (forward) to an elsewhere that is not given beforehand – where I am not. He writes: “A car moves, the lens moves within it and outside: here is a film whose subject travels as the film stock does.” He calls this the boîte-regard, the ‘box that looks’ or ‘the box for looking.’

Nancy’s metaphor adds a phenomenological aspect to Perez’s discussion of perspective and subjectivity in Straub-Huillet’s History Lessons (1972). Perez’s claim that the perspective from the back seat and the framing through the windshield and windows (in both Straub-Huillet and Kiarostami) is “the container photography inherits from the tradition of Western painting,” in turn opens up a connection to the ideological theories of French Post-Structuralism that posited that the basic apparatus of cinema reproduces the principles of linear perspective perfected by the Renaissance painters. Their term for the ‘arrangement’ of the necessary elements of cinema is dispositif. Dispositif, however, can also be used in the sense of the cinematographic equivalent of a literary conceit, a preset procedure involving the structures or parameters of the film. The dispositif in this sense has become central to Kiarostami’s art since 10, the period when he started to gravitate toward the art gallery, although it must be said that Life and Nothing More is already a much more Structuralist film than Godard seems to think. If Godard is opposed to conceptualism in Kiarostami in the sense of a structuring idea or system, this can be read as an opposition to the dispositif side in the filmmaker’s work. The critic Alain Bergala, on the other hand, sees this aspect as the Iranian master’s prime virtue. In his notes on the exhibition Correspondences: Erice-Kiarostami (2006-2007) which he co-curated and for which the two filmmakers exchanged a number of video-letters, Bergala notes that theirs is a “more musical and subtler art based on repetition and difference, on seriality, on the device.”I find it striking that among the tributes to Kiarostami in Sight and Sound, Erice’s was by far the most, shall we say, ‘intellectual,’ following Nancy’s characterization of Kiarostami’s ‘presentness’ to the letter and quoting the philosopher’s idea of the boîte-regard as a vehicle for cinematic truth, “out of which emerges an art of looking, sensitive to the movement of things more than to their representation.”

The device of the restricted viewpoint of the fixed camera position in 10 and Five together with the episodic/numerical division and the insertion of strips of countdown leader clearly tie the films to the Structural tradition in avant-garde filmmaking. Structural cinema was crucially influenced by serialism in contemporary music and art that used mathematical schemes to generate compositions. The idea was that composition would not be determined by melody or harmonic tension but by the devising of rules which would govern the musical structure. Minimalism, the art movement based on clarity of form and simplicity of structure with which Kiarostami’s cinema and photography has regularly been associated, grew out of the ambitions in serial art and music towards objectivity and reduced self-expression (Sol LeWitt: “The idea becomes a machine that makes the art”). Minimalism, both in art and music, typically highlights the reduction achieved by repetition, structures of iteration that regularly appear in Kiarostami’s films from Orderly or Disorderly (1981) onwards: while the only slightly varied trips from Koker to Poshte and back again in Where is the Friend’s House? and Mr. Badii’s meandering drives to and from his hill-set grave in Taste of Cherry still conveyed a mythical, cyclical or seasonal sense of time, and Behzad Borani’s endless drives to ‘higher ground’ to facilitate cellphone reception in The Wind Will Carry Us were characterized by a Beckettian or Keatonesque absurdity, with 10 repetition has become a modular or systemic device, a ‘machine,’ in its own right. A simple schematic structure or codified value was also at the basis of Five (Dedicated to Ozu): five long takes of natural landscapes, about 16 minutes each, of which four were taken from a static camera position in the manner of the structural landscape films of Larry Gottheim, Peter Hutton and James Benning. Aleatory music, another context for Kiarostami’s ‘elimination of the artist’ in these films, is closely related to the serialist program if only because the decision to leave elements of a composition to chance (what Cage called “indeterminacy of composition”) is a ground rule or generative device. Once a ground rule of any kind has been established, the music can unfold of its own accord, the composer/director becoming as interested in how things will turn out as the viewer or listener. For all its Bazinian undertones, this is essentially what Kiarostami means when, in 10 on Ten, he qualifies that eliminating directing and the director does not mean eliminating the auteur because video gives both director and the audience the possibility of discovery (Godard’s ideal). The central idea of aleatory music centered on the ability of a piece to be performed in substantially different ways, with composers providing room for musicians to improvise during the performance (what Cage refers to as “indeterminacy of performance”), also fits Kiarostami’s direction of actors in 10 who, more than ever before, become co-creators in the Rivettian sense.

La Loi du silence

So – paradoxically given Godard’s critique of what is systematic in Kiarostami – what unites serialism, indeterminacy and minimalism is not only the grounding of complexity in simplicity but the stance of being open and receptive, of letting go and traveling where the work will take you rather than making things happen, a lesson learnt by the filmmaker characters in Life and Nothing More and The Wind Will Carry Us. The art historian Meyer Shapiro characterized Cézanne’s art precisely as one of “grave attention,” while Ernst Gombrich writes that it is a wonder Cézanne succeeded in making art all: “If art were a matter of calculation it could not have been done; but of course it is not…It suddenly ‘happens,’ and nobody quite knows how or why.” Similarly, Heideggerian unconcealment demands most of all paying close, respectful attention. Late Heidegger is all about waiting, being open and receptive, not bully things into giving up their goods, bending them to our will. There are of course filmmakers whose fortuity was legendary – the breeze lifting Maureen O’Hara’s veil at exactly the right moment during the wedding ceremony in Ford’s How Green Was My Valley; Rossellini ‘finding’ his film at the Pompeii excavations in Viaggio in Italia then building the narrative around it – but Kiarostami, not sharing the luck of the Irish or the Italian faith in miracles, knows that he has to help things along a bit, by rigging an apple falling or painting a house blue and trimming it with flower pots. Film is a medium of time, but time is something that on a feature film production – no matter how small the crew – you rarely have. In Notes sur le cinématographe, Bresson defends a similar position of patience and receptivity, quoting Camille Corot’s variation on Picasso famous, “I don’t search, I find”: “Il ne faut pas chercher, il faut attendre.” J.M.G. Le Clézio’s 1988 introduction to the Notes grounds both the book’s aesthetic principles and its epigrammatic form to the reductive simplicity of Buddhism:

Reading these notes, we may also think of oriental artists, Hokusai for example, in connection with Zen Buddhism. There is the same sense of economy, the same liking for what is sensual, and the same play on all the senses. Life drifting, in its continuous, unpredictable flow. Life inimitable. Japanese Buddhism teaches us that art (or bliss) is surprise, it cannot be calculated. It is a prey, a catch: “Be as ignorant of what you are going to catch as a fisherman of what is at the end of his fishing rod.”

Many have puzzled over the dedication of Five to Ozu, but it makes perfect sense considered from the (somewhat misguided) conception of Ozu as a Zen-like director who prized precision, objectivity and simplicity above everything else. John Cage’s interest in indeterminacy was similarly determined by his interest in Zen Buddhism, which he studied from the late forties onwards. Both the groundbreaking Music of Changes (1951) and the spin-off piece Seven Haiku (1951-52) were composed according to a chart of 32 moves derived from the I-Ching. Kiarostami has written haiku-like poems (collected in two books, Walking with the Wind (2001) and A Wolf Lying in Wait (2005)) that closely follow the delicate, lyrical, minimalist imagery of his photography. In these poems Kiarostami does not stick to the syllable pattern of haiku but keeps its brevity, focus on natural elements and seasonal references (cherry blossoms, clouds, moon, mountains, streams, snowflakes) as well as its ephemeral feeling or mood conveying the impression of ‘a voyage that lasts a mere instance.’ Some of the strongest images in his films were inspired by the haiku-like poetry of Khayyam, notably the sunset-moon-sunrise pattern of the final part of Taste of Cherry. A modern-day practitioner of the mode like Sohrab Sepehri, one of the first to translate Japanese poetry into Persian, was the inspiration behind Where is the Friend’s Home?, a film that takes its title from one of his poems and is dedicated to him. The Wind Will Carry Us, Kiarostami’s most self-consciously ‘poetic’ film, starts with the unseen passengers of a 4×4 driving through beautiful countryside quoting Sohrab: “Near the tree is a wooded lane more green than God’s dream.”

His half-hour video, The Roads of Kiarostami (2006), produced by a South Korean environmental group, finally, has Kiarostami reading extracts from Sohrab over a montage of his landscape photographs set to Vivaldi and culminates in a filmed sequence of the director photographing a dog in a snowscape of barren trees set to Japanese flute music that underlines the connection between classical Persian poetry and Japanese haiku established in the film. When in the last shot a close view of a dog is superimposed with an orange red blast of an atomic bomb, the landscape film becomes an indictment of Ahmadinejad’s nuclear program and another connection is established, to Andrei Tarkovsky, a kindred spirit and master of the cinematic haiku form.

In Sculpting in Time (1986) Tarkovsky acknowledges Eisenstein’s use of the three-line structure as a model for dialectical montage, but situates his own interest in the form elsewhere:

What attracts me in haiku is its observation of life — pure, subtle, one with its subject; a kind of distillation. This is pure observation. Its aptness and precision will make anyone, however crude his receptivity, feel the power of poetry and recognize — forgive the banality — the living image which the author has caught.

Tarkovsky’s qualification of the haiku as “pure observation” steers close to both de Clézio’s evocation of Buddhist naiveté and to Mallarmé’s definition of Impressionism as the ability to “see nature and reproduce her, such as she appears to just and pure eyes.” At the same time it renders explicit the formalist dimension of Impressionism which, as Gilberto Perez has argued has often been obfuscated: while it appear artless in is simplicity, the haiku is a ‘distillation,’ a precise rendering that allows us to see something for what it is. What also imposes itself on Tarkovsky is the riddle contained in an art that ‘cannot be calculated’ or deciphered:

What captivates me here is the refusal even to hint at the kind of final image meaning that can be gradually deciphered like a charade. Haiku cultivates its images in such a way that they mean nothing beyond themselves, and at the same time express so much that it is not possible to catch their final meaning. The more closely the image corresponds to its function, the more impossible it is to constrict it within a clear intellectual formula. The reader of haiku has to be absorbed into it as into nature, to plunge in, lose himself in its depth, as in the cosmos where there is no bottom and no top.

What Tarkovsky is evoking here is the genre of the ‘Koan’, Buddhist riddles that often turn around the idea of ‘mu’, the negative. Heidegger was greatly interested both in Koan – an interest no doubt inspired by his Japanese student and later Buddhist philosopher Keiji Nishitani – and in Zen art in general, the subject of his 1958 discussion with philosopher and Zen-master Hoseki Hisamatsu, ‘Thought and Art.’ According to Hiamatsu, for Zen the beauty of the artwork lies in the fact that, somehow, the formless comes to presence in the pictorial. Without this presence of the formless itself in the formed, a Zen artwork is impossible. Along similar lines, the late Heidegger argues that ‘unconcealment’ also and necessarily contains a negative, a concealing: the disclosed world has its basis in the materiality and opacity of ‘earth’, a ‘mystery’ that cannot be revealed or un-hidden, even as its being at work can be revealed in the reflective moment of the artwork’s relation to a beholder. Truth cannot be disclosed directly but always appears as a combination of riddle and clarity, of the ineffable and the utterable, of the holy and immanent. While Nô theatre is offered by Heidegger as an example of an artistic practice where the ‘empty’ or the ‘formless’ interact with the pictorial (think also of the formless or ‘negative space’ parts of a Cézanne painting), cinema, oddly, serves as a counterexample: because it cannot avoid providing a denseness of naturalistic detail, the cinema cannot allow anything but the concrete, the at-hand to become visible. The example Heidegger has in mind is Kurosawa’s Rashomon. Had he seen any of the ‘transcendental’ filmmakers – Bresson, Deyer – he would surely have come to a different conclusion. Also, Bazin argues (in ‘The French Renoir’) that the plenitude of the image, the density of naturalistic detail, is precisely what makes us aware of a necessary absence: “The significance of what the camera discloses is relative to what it leaves hidden.” Like Bazin, Nancy offers that the “evidence of cinema” is not only that of “the existence of a look through which a world can give back to itself its own real” but also that of “the truth of its enigma.” Evidence always comprises a blind spot within its very obviousness, something that “resists being absorbed in any vision” (whether world view, representation or imagination). This blind spot he calls “earth” and “clearing,” two Heideggerian conceptions.

The ‘clearing’ is a metaphor evoking a bright forest glade in which things are not named or instrumentalized but merely exist in their mode of being. It is no exaggeration to say that this clearing, for Heidegger, more or less coincides with the aesthetic experience. The clearing is not a zone for action or imposing but for “letting being be,” for letting earth “shine” through (as in the colors of a Cézanne), for the contemplation of the mystery, for “thinking the real, to test oneself with regard to a meaning one is not mastering”’ It is a letting go, not really philosophizing any more, more a form of meditation. Essential to the look that creates the clearing is ‘regard,’ in the sense of ‘in relation with,’ but also, and especially of ‘care’ and ‘respect’ (égard). ‘Letting be’ and ‘care’ or ‘respect’ designate an art, not of big statements, but of stillness and repose, simplicity and tranquility, an ‘intimation of silence.’ This is the Heidegger of the Holzwege, the Black Forest philosopher humbly listening to the trees, skies, stars, or to the ‘song’ of a poet like Hölderlin who was convinced that the sacred can only be grasped in silence. Matisse praised a similar kind of sublime silence – the mode of Cage’s 4’33’’ but also of Kiarostami’s Five or the films of Peter Hutton and James Benning – in Cézanne’s series of paintings of his wife Hortense, Portraits of Madame Cézanne (1883-1885), which he had acquired and that served as inspiration for many of his own portraits of sitting figures. Gombrich cites the same portraits to illustrate how greatly Cézanne’s concentration on simple, clear-cut forms contributes to the impression of poise and tranquility. The silence of Cézanne is perhaps best captured by Heidegger’s haiku-like poem inspired by another portrait, of Cézanne gardener Vallier, the subject of his seven final paintings.

The thoughtfully serene, the urgent

Stillness of the form of the old gardener

Vallier, who tends the inconspicuous on the

Chemin des Lauves

In Godard’s Nouvelle Vague (1990), a film that actually contains a haiku, or in Godard’s words, “something that conjures an image” – “Snow on Water/Silence on Silence” – there is a middle-aged gardener, Jules, who in his earthy sage-like temperament and serene, caring disposition, much resembles Vallier. His groundedness – his ‘at-homeness in the world’ – is what allows him to voice the evocation of the clearing: “Let the world be without name for a time. Let things listen to what they are. In silence, in their own time and their own way.” In view of Jules/Vallier’s invitation, you could argue that what Kiarostami shares with Godard is the ambition to express truth, meaning, profundity in a non-metaphysical way, through what you could call ‘poetry’ (or ‘song’, in both Hölderlin and Maurice Blanchot’s terminology), that, for all its sonic plenitude, cares for silence. Although in late Heidegger, silence as ‘nothingness’ is a nothing of plenitude, a nothing that is other than beings but still something, both a horizon, a grounding for being and a richness of concealed (and ungraspable) possibilities of disclosure, like in a lyrical poem, in his early works that influenced French Existentialism and inspired much of modernist art cinema, ‘nothingness’ means emptiness, darkness, the abyss, death. It causes a horror vacui that produces anxiety, Angst. Some of the more striking passages in late Godard and Kiarostami are passages of darkness and night related to death: in Taste of Cherry, when Mr. Badii is lying in his grave and sees clouds drifting across the moon the image fades to black and we are left in darkness. The distant rumbling of a thunderstorm is heard on the soundtrack, then lightning flashes pierce through the darkness before a thick dark mass envelops the screen for a long minute. Kiarostami has said the following about this sequence:

For me, the film ends in black night. What I wanted to do was to register the awareness of death, the idea of death, which is only acceptable in a film. That is why I left the screen black for a minute and a half. My colleagues told me this was too long, and audiences would walk out. But this shot in total darkness needed to be prolonged so that audiences would be confronted with this void, which for me refers to the symbolism of death. To look at the screen and see nothing.

Kiarostami returns to this idea of the voided image or the ‘image-void’ on several occasions: in ABC Africa the screen goes almost completely black for seven long minutes when the electricity in the film crew’s hotel goes off. In the final episode of Five the reflection of the moon in a pond suddenly fades out and we are left with a ‘chorus of sounds’ for a good five minutes. Godard stages a similar concealing in Hélas pour moi (1993), his version of Jean Giraudoux’s comedy Amphitryon 38 (1929) in which Jupiter/God assumes the form of Amphitryon/Simon to seduce his wife Alcmène/Rachel. When God-as-Simon engineers a day-long night to work his charm, the image fades to black; then there is a cut to a shot of Rachel with her back to the camera, moths fluttering in the backlight (Mothlight?) as God/Simon rips off her dress; at that precise moment, the image goes dark again and – as in Kiarostami – we hear the rumbling of a distant thunder storm. The passage brings to mind a poetic text from Histoire(s) du cinema:

Yes, the image/ is joy

but beside it

dwells nothingness

and all the power

of the image

is expressed

only by evoking nothingness

The image

capable of negating

nothingness

is also the gaze

of nothingness upon us.

In the darkness God/Simon narrates the story of John Oort, the Dutch astronomer who developed the theory of ‘phantom matter,’ the invisible part of the universe, the scientific counterpart to the idea Heidegger took over from Rilke of the dark side of the moon, an ungraspable area of unperceived darkness. Godard, here and elsewhere – in Histoire(s) where Oort’s precursor Ernst Opik’s theory of the unseen backside of he planets is cited, for example – evokes nothingness as invisibility. In the short video Dans le noir du temps (2002) a scene is resumed from For Ever Mozart (1996) in which the elderly film director Vicky Vitalis explains that night is dark because the universe has grown old and when you look at the sky between the stars you can see what has disappeared. Again, darkness, night, implies a cosmogony, the disappearance of the gods (Godard cites Pessoa: “Everything was asleep as if the universe was a mistake”).

Mehr Licht!

Hölderlin’s trope of a deep and long night resulting from the disappearance of the gods is felt most deeply in his evocation of the opposite, the ‘festival,’ the meeting of gods and men. For the late Heidegger, the Greek festival means the cessation of work, allowing us to “step into the intimation of the wonder that around us a world worlds at all, that there is something rather than nothing, that there are things and we ourselves are in their midst, that we ourselves are.” This kind of ‘Feier-tag’ is what happens in the coda of Taste of Cherry, as convincing an evocation of Elysium as the cinema has ever produced. In Hélas pour moi on the word ‘visible’ in God/Simon’s monologue on Oort, the flickering light of a sparkler brings light in the darkness, illuminating Rachel’s naked lower body (an image somewhere between Botticelli and Courbet). In Kiarostami the progression from darkness to light is more gradual but remarkably similar in the three instances I’ve mentioned: first there is lightning and rain, then the dawn (Kiarostami also made an entire film, The Birth of Light (1997), showing a sunrise in an Iranian mountain landscape using time-lapse technique).

The light coming through the darkness provides an allegory of cinema that is at the same time simple and complex. First there is the nature of light as divine. In Straub-Huillet’s Cézanne in conversation with Joachim Gasquet one of the inserted clips from their The Death of Empedocles (1986), highlighting the continuum Hölderlin-Heidegger-Cézanne in their work, makes explicit the connection between light and the days of youth, before the gods abandoned Empedocles and he first awoke to the divine world:

O heavenly light! Men

had not taught me – for a long time

When my longing heart could not find

The All-Living, then I turned to you

Second, there is the direction of the light. The light on Rachel in the night scene from Hélas pour moi comes from behind, but since she is turned with her back to the camera you can just as well say that it comes from the front. Godard has tied these two directions to the cinema’s core properties of recording and projection. A camera, Godard has said, has to be in front of light:

You go to where the light is coming from. Like in the Bible. The shepherds were going in the direction of the star. And then the characters are found in the shade with the light behind them. The laws of this have been established by Newton, Einstein, and others: there is a correspondence between light and matter, and light is matter and energy. So when I go in front of the light – go towards it – it is because it brings me energy.

Projection, on the other hand, is what comes from behind, what animates a world, what brings it into existence. What Godard takes issue with in Kiarostami is that the light of his intelligence has superseded both the light of the world and the light that brings it into being (“It is not the light of the thing, like when Cézanne paints an apple or a glass”). At the time Godard made the statement he could not have foreseen that the last film Kiarostami shot before the dying of the light, was a tribute to Lumière.