Voice can be like a guiding light. It controls our eyes, tells us what to focus on or ignore, it reminds us that someone is behind the camera, making choices about what we see. The use of the voice as a narrational tool reveals the broad notion of the documentary form being an exclusive hunt for truth as a silly one. The imposition of narration is an unmistakable stamp of authorship and control. This makes way for the entrance of the raconteurs, personal documentarians who turn their truth into cinematic fact. The voice-over is a commandment, and there is none more conventionally authoritative than the English language male voice. Several particular voices stand out as utilising or undermining authority, in ways that reveal a far more complex combination of facts with downright lies in order to get at a personal expression.

Adam Curtis himself never appears on screen, and yet he has become a popular documentary personality. His style, a rummaging through of the BBC archives for vivid images from history, accompanied by ironic music, is incomplete without his Received Pronunciation (RP). His latest film, the 8-hour Can’t Get You Out of My Head (2021), illustrates the effect of RP, the typically British accent of newsreaders and Shakespeare performers, often labelled ‘Queen’s English’. With his disarmingly high-pitched, haughty voice, Curtis will make broad links between seemingly irrelevant moments: the cultural revolution in China will be linked to the killing of Tupac Shakur through a single cut, with a declarative statement delivered like a BBC News alert, as the band-aid. “Richard Nixon came to power because he had harnessed a new force,” he will say with certainty. Without the time to fully explain himself, Curtis relies on his own force of voice to combine with the nostalgia that his chosen images evoke, to present an emotional argument. He papers the walls of his thin arguments with sheer conviction. It’s that much harder to write off a conspiracist if they wear a suit.

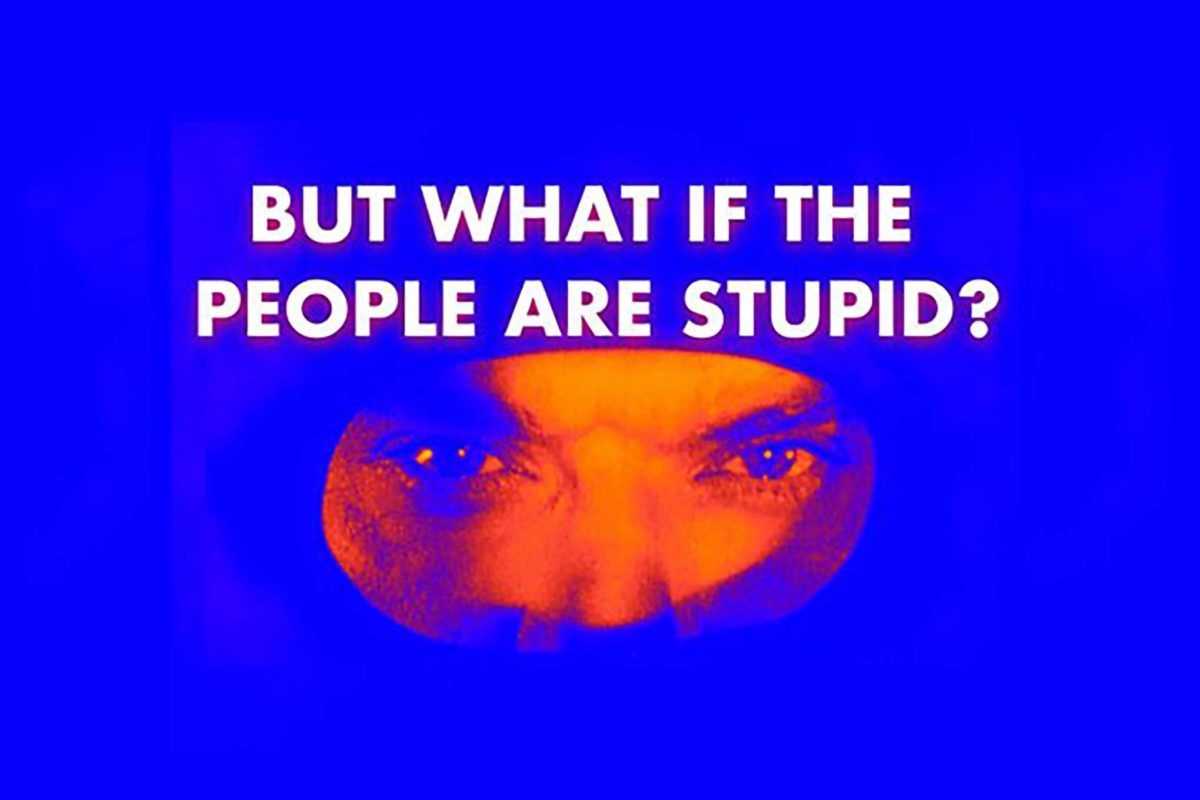

Can’t Get You Out of My Head has received a significantly greater amount of attention and criticism than his earlier films. It is significant, then, that Curtis has appeared more willing to be perceived as an artist-filmmaker this time around. Much as he calls himself a journalist, a quote from his film adorns the April Sight & Sound cover with messianic boldness. It is his words, not his face, that matter, the magazine tries to tell us. But stripped of that RP delivery, quotes like “THE WORLD IS WHAT YOU MAKE OF IT” come across more like the aphorisms of Nathan Barley, the mid-2000s new media hipster parody invention of Charlie Brooker and Chris Morris. Curtis is far more convincing when he guests on podcasts like Blindboy and Red Scare, where he is permitted, nay, encouraged, to monologue on the state of things. Like in the East London of Nathan Barley, where the aesthetics of rebellion are an essential commodity to keep stuffed shirts and liberal editors happy, the gestures of ‘alternative’ podcasts and the current Sight & Sound iteration are mere window dressing to the same old hegemony. This makes Curtis ever-popular: it is the delivery that matters more than the substance of his argument. As Kanye West opined in a 2018 tweet, recommending Curtis’ The Century of the Self (2003), “It’s 4 hours long but you’ll get the gist in the first 20 minutes.”

Curtis is not entirely an outlier. In Of Time and the City (2008), Terence Davies’ plum, musical tone drives his recollections of post-war Liverpool. Having developed an unmistakable style of slow panning shots in his autobiographical films like The Long Day Closes (1992), his breathy readings of Shelley and Joyce are like an aural dream, rhythmically entwined with the visual style that he assembles through his choice of archival clips. Davies’ authority is an utter familiarity with the place, his quotes and clips approximating a remix of the Liverpudlian spirit: a down to earth, working class community with a strong connection to water through the UK’s revolutionary Royal Albert Dock, and the alluring river Mersey. He becomes an anti-Curtis: still a voice of the British establishment, but as a working class boy done good. Davies doesn’t take ironic distance, or ask us to hunt for hidden meaning. Where Curtis drives through the footage with a reporter’s breeze, Davies floats above it, like a Muriel Spark narrator, or a DMT trip.

As hallucinatory as Davies and Curtis can be, neither are the stoner icons that American raconteur Caveh Zahedi has become. Zahedi has no time for archival footage, nor does he attempt grand statements. In the tradition of that scoundrel of the cinematic memoir, Ross McElwee, whose love-life and family chronicles in the likes of Sherman’s March (1986) have him labelled a misogynist and a bore, Zahedi is a personal filmmaker as diary dilettante and self-flagellator. Across a number of memoir films Zahedi is his own subject, developing a sitcom-esque schlemiel persona that blurs fact and fiction. In I Don’t Hate Las Vegas Anymore (1994), Zahedi attempts to reconnect with his father and half-brother by coaxing them into dropping ecstasy with him and his film crew during a trip to Las Vegas. With staccato, anxious delivery, he over-shares about the circumstances of the production. From Woody Allen to the characters of Charlie Kaufmann, viewers have been—for better and for worse—previously encouraged to trust this rapid-rambling delivery as someone intellectually self-possessed and worth listening to. His various tales about film production, family ties, and deviant behaviour are thus brought together with a convincing energy.

Zahedi will often speak directly to camera, endlessly unspooling his thought process with neurotic, self-impressed, sexually depraved glee. Recalling the opening of Allen’s Annie Hall (1977), he is almost always framed against a blank background, never more explicitly than in his television opus, The Show About the Show (2017-2019). In this film, in which each episode reconstructs the previous episode, Kiarostami-esque ambitions give way to Real Housewives narcissism through the leanings and emphasis of his voice, more interested in sex than form. (And who can blame him?) Zahedi’s process seems to be uncovering his own self, and it is only Eros that can be found there. With In the Bathtub of the World (2001), Zahedi attempts to chart a year of his life across one-minute clips, in a precursor to the 1 Second Everyday app. One’s interest in the project will vary depending on how captivated one is by character. And yet, it is his shrill, nebbish voice that holds the persona together, and has successfully sold him as the paramour of hip Independent filmmaking (Zahedi, too, has a podcast). But listening to his stories exclusively in audio form has little of the same appeal as watching his skull bob around his slender neck, attempting to navigate his own foibles through a mixture of anecdote, reconstruction, and voice-over. He shows the limits of the English language voice to adequately tear oneself down.

If one documentarian’s life has played out before the camera more extensively than Zahedi, it would be Werner Herzog, more meme than man, an entirely played out persona of filmmaker-as-crazy-person. His casting in Rick and Morty delivering existential monologues, and the Disney+ programme The Mandalorian as a cog in the creative wheel of showrunner Jon ‘Chef’ Favreau, tells us that Herzog is such an oversaturated figure in popular culture that he can be used as a shorthand to gravitas by lazy TV writers. His entire career is constructed from such watercooler moments. He threatened to murder his star, Klaus Kinski, on the set of Fitzcarraldo (1982). He was shot with an air rifle while being interviewed by the voice of British film criticism, Mark Kermode. He filmed a penguin walking against the tide in Encounters at the End of the World (2007), “heading towards certain death.” The only thing holding Herzog’s sloppy search for ecstatic truth together is the Bavarian accent. He plays on Anglo-American understanding of the European voice as something more refined, and ultimately underlined by evil via links to Nazism and 100 years of Hollywood stories about Nazism. (The irony of making such a statement in the pages of esteemed Belgian publication photogénie is not lost, but as an Englishman of French heritage I feel in possession of the authority to say.)

In Grizzly Man (2004), Herzog listens to the tapes of its subject Timothy Treadwell being torn to death by the wild bears he thought he’d developed a relationship with, telling Treadwell’s girlfriend Amie Huguenard, “You must never listen to this.” His line effectively becomes the death audio for viewers. We hear the Bavarian accent instead of the dying man’s screams. Search online for the tape, and Herzog’s voice is all you will find, his ecstatic truth trumping all others. Similarly, searching for the niche films of all stripes that cinephiles are inclined towards, Google is likely to turn up podcasts and video essays: two mediums that are driven by the English language voice as a supposed guide through the matrix of both film culture and everyday life. The Podcast form traditionally presents itself as a public-access radio show with no limits, a portal to the counterculture. This can be typified by The Joe Rogan Experience, wherein the ex-Fear Factor host plies his guests with stimulants to help them open up about the strangeness of the modern world. That every media company has hopped on the trend (stimulants unconfirmed) as a way of ‘casually’ reaching consumers is no surprise: The A24 Podcast, which parlays the indie studio’s hipster cache, features discussions between novel filmmaker pairings like Joanna Hogg and Martin Scorsese.

With such authorities providing a route through film culture, one wonders if there is a use for Mark Cousins. Another believer in the poetry of cinema, his films, all uniquely sentimental puff-pieces about the power of the cinema, celebrating the innocence of a child’s eye view, are driven by that voice; a lilting brogue that stems from his Belfast/Edinburgh upbringing. It’s a make or break sound that intends to capture the imagination of the cine-curious. For many though, hearing him narrate 915 minutes of The Story of Film: An Odyssey (2011) is enough to justify the rapid decline of the movie theatre. Perhaps he has taken this on board: Cousins’ latest adventure, the 14-hour Women Make Film (2018), is a self-styled ‘road trip through cinema’. Instead of imposing his male voice-over onto the clips he has chosen of films directed by women, Cousins defers to female authority figures to read his script: Tilda Swinton; Jane Fonda; Thandie Newton; etc. Watching Women Make Film, I couldn’t help but recall the doped out voice of Laura Poitras at the start of her Citizenfour (2014), who also reads the words of a male auteur. As lights of a tunnel pass overhead, Poitras slurs a letter from Edward Snowden, “this will not be a waste of your time. The following sounds complex, but will only take minutes to complete for someone technical,” s/he intones, establishing the atmosphere that pervades the film: part mid-00s Assayas thriller, part grandiose mockumentary.

The narrating voice in documentary is nothing but a trick to convince us that we are watching something true. So, who else could be its grand magician but that devil, Orson Welles? Ever the centre of our cinema solar system, Welles displayed the tendencies of the personal, the public, and the private, before blowing them all up in his documentary F for Fake (1973). An infamous pariah of the old Hollywood, by the time he made his documentary, Welles had largely moved to appearances on the likes of The Dean Martin Show (1965–1974), embracing his essential abilities as a showman and entertainer. If his roaring laugh is anything to go by, he was clearly loving it. If he was alive today, it’s doubtless that Welles would have appeared on every podcast in town. Indeed, re-emerging onto cinema screens in 1973, F For Fake gives us the sound of Welles before we see him. Referring to himself as a charlatan, the large figure eventually emerges, donning a black suit replete with a cape, hat, and cane. The film tells a wide-ranging conspiracy of fakery: fake art, fake personas, a fake film. His booming, Shakespearian voice leans on bathos and the anti-punchline to utterly control the viewer’s perspective, while his on-screen presence as the famous, and the ageing Mr. Welles frequently disrupts his storytelling. Bouncing from an interview of the writer Clifford Irving, the ‘author’ of Fake (a book about art forger Elmyr de Hor), to scenes of him dining and downing wines with the man, Welles cannot help but interrupt from the editing booth, “Sorry I’ve been jumping around like this because that’s the way it was.” Before cutting to shots from his holiday in Ibiza. As though undermining his own authority as mysterious master auteur, Welles nonetheless understands that such lines of voice-over are enough to convince the viewer that his tall tale is at least going somewhere.

Like Zahedi and Herzog, he takes the long way around a simple story by clashing the power of his image and voice. The clash would never cease. Welles went on to narrate the Larry Jackson film Bugs Bunny: Superstar (1975), a hack pasting of several Looney Tunes shorts, with Welles’ explanation of the history of American Icon Bugs as the glue to convince viewers they were watching a real-deal piece of work. Welles used his own persona to break down the walls of the documentary form, and let the clowns inside. That the likes of Curtis, Caveh, and Cousins follow him through is no surprise. A journalist, a narcissist, and a poet, these three raconteurs see the holes in their stories and fill it with their voices to varying levels of success. Of the three, only Curtis never appears on camera, but if the podcast is a new essential supplement to cinema then his mask is slipping. All three are so overwhelmed by the power of their voice that, in 2021, they have reached something of a dead-end with their formal projects. In a world overcome by images, their reliance on the voice as a vessel for truth may have been their undoing.