In the few interviews he’s given in English, the Cypriot director Yannis Economides has brusquely tried to avoid being pigeon-holed as a filmmaker who solely grapples with socio-political issues, abundant and pervasive as they may be in modern Greece, where all of his films are set. Instead, he firmly stands behind a more existential reading of his rather bleak, if not outright nihilistic, filmography. According to him, his works offer an honest and realistic account of the most unflinchingly brutal and lowly aspects of human nature, “The darkness of the human soul”, he calls it. Economides enduringly examines this vast and timeless topic, by exploring the daily lives of countless neurotically loquacious miscreants who spend most of their time trying to better their own dreary situation at the cost of someone else’s. The only dramaturgical counterweight to this screaming mass of self-absorbed characters is, in most cases, a reticent figure—a man of few words who keeps to himself and tries to navigate the hysteria around him with a sort of stoic resignation, which however always leads him to violent bursts of pent-up anger.

This studious interplay of logorrhea and silence provides Economides with a simple yet useful framework for teasing out the pitfalls of being with others. Through sets of lengthy, repetitive, and profane-ridden quasi-conversations, he easily gets his existential point across—interpersonal relations are a perilous endeavor in a world where everyone is looking out for themselves. At the same time, this bleak appraisal of the human condition begs the simple question: “Why are people the way they are?” Economides has said that “jealousy, hatred, arrogance, and avarice are just archetypal facts of the human condition” and although his films could be read exclusively through this essentializing lens, there is a case to be made that his works do indeed carry an excess of ambient socio-political meaning, which inadvertently allows them to tackle the question posed above.

Such a conclusion does not necessarily entail that a reading of his oeuvre should fall back on reducing his films to straightforward cinematic representations of a country in crisis. Rather, a more well-rounded approach may instead focus on how a disintegrating state affects the existential well-being of individuals, not through its oppressive actions or failures, but through its absence—its inability to take political measures in the name of the public good. In this sense, Economides’s apprehensions about human nature seem to be revealing and even subtly critiquing how societies strive, fail and, in the case of Greece, often neglect to manage the lowly passions of people. His films are constantly betraying a simple, yet unarticulated truth: there is no pursuit of stable forms of governmentality—there is nothing building up trust in the system and nothing encouraging the productive sublimation of pernicious human desires. So then a disintegrating public sphere, along with a transferal of responsibility to individuals, transforms the private into a locus of unfettered passions and anxieties because in this neoliberal crisis of care and governmentality the underlying sentiment is that it’s every man for himself. Trudging through these sorry circumstances, modern Greeks have found themselves trapped in a vicious cycle of alienation, which the state has created by leaving a void of corruption and malfeasance in its absence.

The makings of this Hobbesian nightmare predate the bursting of the financial bubble in Greece, which has maybe far too easily become an end-all-be-all framework for interpreting contemporary Greek cinema in all of its manifestations, be they the immensely popular “weird ones” (e.g. Lanthimos, Tsangari, etc.) or the more “prosaic” ones (like Economides and Giannaris for example). The reality of the matter is that the corrupt neoliberal political culture that led to the crisis had already been in place by the end of the 20th century and so had left its mark on the public psyche years before the catastrophe hit. Affairs like the Siemens bribery scandal, during which numerous government officials were implicated in money laundering, bribery, and illegal business deals, had already exhausted the public’s faith in the efficacy and transparency of the system, thus contributing to the growing sense of precarity and anxiety for the future.

By subtly reflecting this socio-political situation, early Economides works like Matchbox (2002) grapple precisely with the ripening neuroses of everyday people—with characters whose subjectivity is irreparably deformed by lack of governance and stability. The film explores the hysterical interpersonal dynamics of a lower-middle-class family who can’t seem to stop screaming at each other through an unending series of sweaty fits of blind rage. The oppressively abrasive atmosphere in their stuffy home is enhanced by the claustrophobic cinematography, which constantly and frantically cuts from one contorted yelling and sweaty visage to another. The household has become a stage for the banal tragedies of everyday life – the emotional fallout of infidelity and jealousy, the precarious future of a modest family business, etc. The patriarch of the family, Dimitris (Errikos Litsis), is insecure, deeply misogynistic, and powerless when it comes to dealing with his wife and kids. Like other men in the film (e.g., his brother-in-law, a visiting colleague, and his son), he’s obsessed with what meager means and fragile status he still has and paranoid about the possibility that he’s a victim of female desire and infidelity—a cuckold who’s been made to care for another man’s child.

Thе fear of social impotence and women is pervasive in Economides’s filmography and in a way harkens back to Theo Angelopoulos’s true-crime-inspired feature debut, Reconstruction (1970), which captures the anxieties of its own time when it comes to modernization, domesticity, and the role of women. It’s no coincidence that earlier in his career, Economides has mentioned feeling a part of a Greek cinematic tradition of social dramas represented by directors such as Pantelis Voulgaris, Tonia Marketaki and, most importantly, Angelopoulos. But while his influential predecessor analyzed how the locus of social life and political power shifted from the villages and the smaller towns to the big cities after the Second World War, Economides has sketched out the reverse trend: Athens in Matchbox is almost entirely reduced to a single extended household (i.e. family and friends) and there are no signs of cosmopolitan culture (although we get to hear talk of an Albanian girl, most of it is racist and xenophobic). In other words, the disintegration of the state is seemingly also transforming city districts into more traditional, village-esque, social formations which operate under a more paranoid, patriarchal and isolationist framework. This folkish way of life, albeit having a postmodern urbanistic tinge to it, brings back to the fore the question of women’s precarious position in society. After all, if a wife cheats on her husband, then his household, the only place where he’s seemingly safe from the dog-eat-dog world of the neoliberal village, is suddenly compromised.

What further complicates the figure of the woman in Economides’s films, however, is the fact that—unlike Angelopoulos’s female lead from Reconstruction, Eleni (Toula Stathopoulou), who, while being a murderer, is ultimately portrayed as a victim of misogyny and prejudice—his rather curt heroines more often than not seem to actually get what they want because they ruthlessly pursue their interests to the bitter end. They’re all essentially like Gogo (Maria Kallimani) from Knifer (2010)—she cheats on her husband and gets him killed, but in the end she doesn’t face any repercussions. Furthermore, Economides’s female characters seem absolutely devoid of any traditional feminine characteristics, which is to say that they appear to have shed all male projections that usually dictate what a woman is supposed to be. They are cold, calculating, and cynical, and in a way uncannily similar to the men whose profane language and angry demeanor they mimic with ease. It’s not clear if this is some sort of survival mechanism or an abject form of internalized misogyny, but the only thing that actually separates them from their male counterparts is the fact that they’re devoid of an Other whom they can objectify and fear. In a sense, this lack makes them appear even more callous in the eyes of men because to them women seem impervious to the feelings of helplessness and loss they experience as males in what they consider to be a dissolving patriarchal order. This makes Economides’s films feel at times just as misogynistic as their male characters, but in reality, the director is making a far more innocuous, albeit also more depressing, point: women already have nothing, so there’s nothing to lose and nothing to fear. So, while they may appear as heartless opportunists, in reality they’re just stern realists.

The dejected self-centeredness of Economides’s characters, men and women alike, not only leaves them incapable of love or trust but also propels them to constantly struggle to invoke a fleeting sense of all that is lost by constantly talking about some thing or other. That’s why the dialogue is maddeningly repetitive, with people perpetually reiterating every sentence at least twice by mixing the order of the words a bit or adding an extra swear here or there. As a result, the constant stream of almost meaningless words acquires a sort of chant-like quality, creating the strange sensation that the characters are trying to conjure up the spirit of something that has left them long ago: meaning. If only they could just find the right combination of paltry phrases, they might actually be able to convey an authentic human emotion or thought to their interlocutor. But, even if they’re indeed attempting to reach out and connect with others, Economides’s characters seem to be doing it wholly unconsciously and only through the means at their disposal, e.g. conversations about money (Matchbox), domestic abuse (Soul Kicking, 2006), and pimping off underaged girls (a theme found not only in Stratos but also in Alexandros Avranas’s Miss Violence, 2013). So, strictly speaking, even if they’re able to find the right words to express a genuine sentiment, their position in society and their milieu entail an array of everyday topics that are far removed from any existentially hearty subjects.

That being said, Matchbox is the only Economides film which relies solely on its noxious dialogue to drive the narrative forward. Consequently, the dramaturgical structure is unsurprisingly repetitive and ultimately circular. Even after some ostensibly life-changing revelations are brought to the fore by the end of the film, the characters are incapable of actually lashing out against the vicious circle of hysterical resignation they have succumbed to at some point. Instead, daily life starts over as if nothing has happened, and the hellish, eternal return of domestic discontents and tumultuous squabbles is made apparent. Everyone’s trapped in a never-ending loop of agitation which constantly feeds on the darkness within and the precarious social order without.

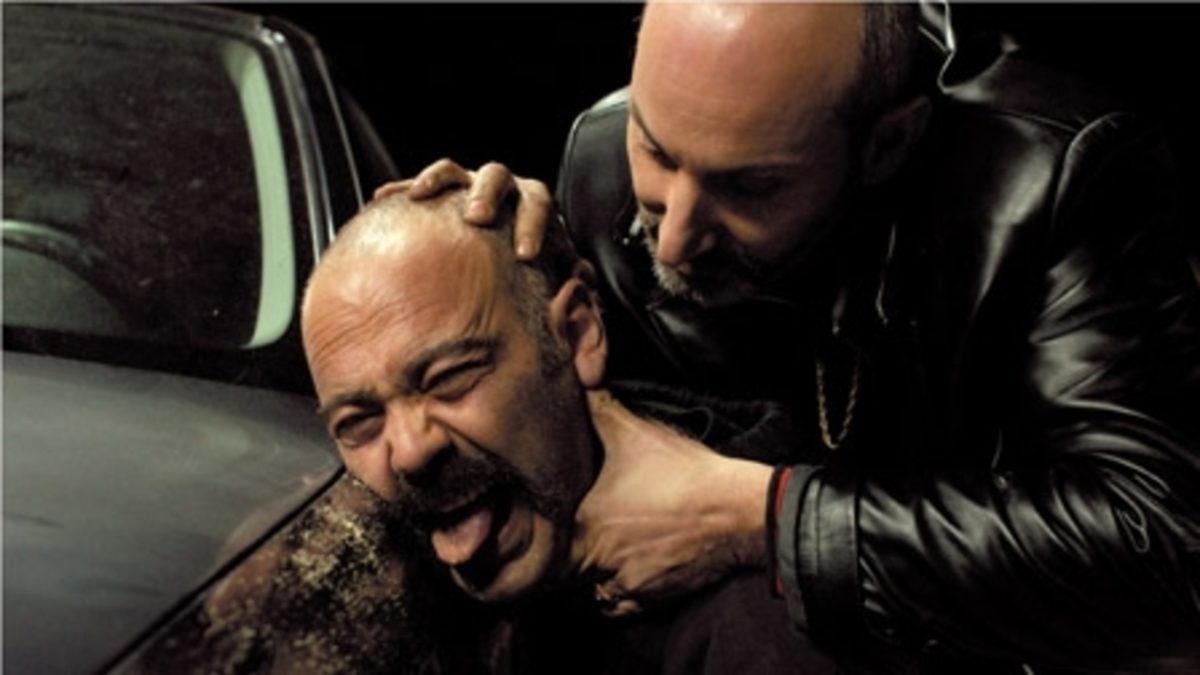

After Matchbox, however, Economides introduces a new type of character, who’s actually narratologically poised to lash out by the finale, which gives him a chance to violently shatter the status quo and help the plot reach a veritable denouement. This is usually a reticent male protagonist who seems alienated by other people’s ineffective and verbose struggle for connection and escape. His stance of silent resignation is favorably portrayed by Economides both as a strategy for survival in a world where everyone vies for attention, and as a means for accruing enough bitterness to reach a point of righteous indignation and discontent in an almost revolutionary manner. In Soul Kicking (2006) for example, the ending of the film finds its impotent, cuckolded, and constantly exploited protagonist Takis (Errikos Litsis) finally snapping and killing his boss, who, while sexually harassing him throughout the movie, was also probably the only person that actually cared for him in some twisted way. Conversely, Knifer (2010) offers an example of a much more calculated approach to harnessing rage and violence—the taciturn Nikos (Stathis Stamoulakatos) plans and efficiently murders his employer/uncle after seemingly falling in love with his wife. In reality, however, he’s just infatuated by the idea of taking over someone else’s household instead of building one from scratch, and his uncle’s wife is nothing more than a symbol of this desire. In a sense, however, Nikos’s and Takis’s actions are equally as meaningless as any of the words that the people in their milieu are invariably throwing at each other. The first one is reproducing the same paranoid patriarchal state of affairs which led to his uncle’s death, and the second one is probably just going to go to prison without accomplishing anything of worth on the level of the interpersonal or the social.

Nonetheless, in Economides’s next and most mature work, Stratos (2014), the eponymous protagonist (Vangelis Mourikis), a killer for hire, also goes out in a series of ugly murders, but at least he saves a little girl in the process, who was going to be pimped out by her heartless relatives to some mafioso. Before that Stratos, like the rest of the director’s protagonists, seems stuck in an infinite and grey loop of strife and violence. Yet, he also silently hopes that life will change when he busts his boss out of prison (which turns out to be an absolute pipe dream). It’s as if Economides has turned Waiting for Godot into a miserabilist social drama where the lead character is constantly looking forward to the day when meaning will reappear with the return of an absent, yet authoritative fatherly figure. In this sense, the restrained cinematography mirrors his meticulous and rather ascetic lifestyle which accommodates only work and anticipation.

After, however, it is made clear that his Godot (the crime boss Leonidas played by Alekos Pangalos) is never going to arrive, Stratos paradoxically regains his agency and breaks the cycle of violence he’s been perpetuating and actually tries to make a real difference unlike all of the other aforementioned characters. His weirdly brutal act of kindness (killing the little girl’s self-interested relatives) is actually what makes this film Economides’s most surprisingly sanguine one. Stratos, as flawed and as irredeemable as he may be, is able to conserve an untainted morsel of innocence in the world. Not only that, he also preserves this girl’s future—the possibility that she might grow up to be a different kind of person than him and everyone around him. It’s a wager of faith and hope which is uniquely powerful precisely because it appears in the context of Economides’s grim vision of reality where hell is always just around the corner.

Going back to the question of the social and the existential in Economides’s films, it becomes clearer how even in the face of absolute hopelessness, the director’s characters actually constantly strive to break away from the nihilistic impasse that comes with essentializing the “darkness of the human soul”. Even if their endeavors are ultimately futile, they still display an unassailable drive to transcend their circumstances and their own failings. They are bitter anti-heroes concerned with the immediacy of the here and now, which is unavoidably social/political and never purely personal/existential. Their struggles with the unbearably ugly truths of human nature are constantly being mediated by a dysfunctional social order and by a concrete historical time and place. That’s why Economides’s films can be both a universalist study of timeless human shortcomings and an expression of the desire to transform the here and now of being with others, which ultimately is: a political issue.