Every minute, hundreds of bodies traverse the crumbling edifices and grimy alleyways of monochrome Athens. In Greek films from the post-World War II period, the environment is one of oppressive tension and looming shadows. Beggars ask for whatever someone is willing to spare, while shady figures exchange piercing looks by the docksides. The aura of urban decay washes over every corner of the Mediterranean metropolis, and yet, its suffocating atmosphere doesn’t seem to distress those inhabiting it. Their hurried strolls continue unfazed by the environment. Perhaps it’s self-imposed denial as a coping mechanism for post-war devastation. Maybe it’s the simple urgency and frenetic pace of modern life. But, even if they go unnoticed by the characters, the mournful ambiance that exudes from the setting is fully palpable to anyone watching the earlier examples from the Golden Age of Greek Cinema. Beyond the facade of a hyper-efficient modern society making its way up from historical catastrophe, lay a melancholic undertone; a connective tissue that bridged individual wounds with a wider, collective search for meaning, expressed through a myriad of contrasting artistic perspectives and dissenting central figures seeking their own paths beyond societal expectations.

The scene in question was a recurrent sight in Greek films during the 1950s, a couple of years before the trend of gritty naturalism eventually evolved into more ambitious aesthetic endeavors. While the finer details in terms of geographical location and social milieu vary between works, the notion of a society in flux is ever present. The defining character archetypes and narrative beats favored by this generation of filmmakers all seem to reflect on a context of socio-economic uncertainty and national identity crisis. After all, these so-called cinematic halcyon days lie stuck between two of the most catastrophic occurrences in Greece’s modern timeline i.e. the German occupation during WWII, and the Colonels’ Dictatorship in the late 1960s.

As one of the central battlegrounds in the Balkan Peninsula during WWII, the Mediterranean nation was devastated by constant warfare, and ended up occupied by the Axis powers. Liberation came in 1944, but what remained of the once glorious bastion of universal culture was now in shambles. Even if the threat of fascist domination had been addressed, its reverberations were still felt by a disarticulated collection of distinct communities and effervescent political ideas. Just a couple months had gone by before a new call to arms came by way of an ideologically polarized Civil War.

The confrontation subsided by 1949, and the defeat of the Soviet-backed Democratic Army of Greece at the hands of the right-wing Greek government army presented the mirage of some deeply needed stability. That was precisely the backdrop of the Hellenic nation’s audiovisual renaissance: A time of deep uncertainty and candid hopefulness, anchored by the promise of a new beginning. An ideal context for a medium forever known as make-believe to thrive on.

After all, the emerging crop of new Greek artists had their own first-hand experiences dealing with the oppressive political atmosphere of the post-war era. Filmmakers that held socialist beliefs were either forcefully exiled and imprisoned in Makronissos, like Nikos Koundouros, or simply fled the country until the waters calmed down, like Michael Cacoyannis. But soon enough, at the faintest sign of a semi-stable political context, this communal sense of alienation was channeled through the arts, as a high volume of local motion pictures began to flood Greek cinemas for the first time since the great exodus of talent during the authoritarian Metaxas regime in the late 1930s. Names like Grigoris Grigoriou, Stelios Tatasopoulos and Giorgos Tzavellas took in the enthusiasm oozing from the post-war creative environments, and put forward some of the best regarded films of the earlier part of the 1950s. These were accessible narratives dealing with daily moral conundrums and stylized intrigues, all while also holding a profoundly reflexive perspective on their socio-economic surroundings.

The influence from the revolutionary aesthetics and deeply-rooted humanism of the neighboring Italian neorealism was unquestionable. After all, despite their different cultural situations and filmic traditions, the questions raised by the early films of Visconti, Rossellini and De Sica had a direct grounding in societies dealing with the changing tides of a new collective psyche, such as the Greek one at that particular moment in time. Filmmakers of both Mediterranean countries stepped outside of the film studios, and went to the streets looking for a purer cinematic form; one that could dialogue with the pressing concerns boggling a desperate working-class. This transition also meant an important tonal shift. The rambunctious high-class comedies both nations were known for looked anachronistic in a context of spiritual search and identitary adriftness.

The shared cinematic path between these nations stops there, however. Besides their philosophical correspondence and focus on historically misrepresented social groups, Greek cinema from this period never really tried to distance itself from artifice like their Italian counterparts did. Classic neorealist elements were still an integral part of the Golden Age films, but so were the aesthetics of film noir and melodrama. Filmmakers embraced both the unparalleled empathic pathos of verisimilitude and the enthralling mannerisms of artifice, resulting in deeply idiosyncratic works, as formally rigorous as socially conscious.

Two of the most representative examples from mid-century Greek cinema can be found in the 1950s output of legendary directors Nikos Koundouros and Michael Cacoyannis. As distinct as they are from each other, both play with the stylistic tropes of 1950s genre cinema (particularly the aforementioned noirs and melodramas) while simultaneously grounding their works within the specific framework of Greek cultural tradition and folklore, exploring in real time the components of an undetermined aesthetic and cultural identity.

In most of their works from this period, there’s a quasi-musical element that guides the films’ emotional bits. Traditional dance and folk music are shown as integral parts of Greek people’s daily existence, offering an a-temporal form of instinctive expression that directly contrasts with the standardized motions of so-called “modern life”. This informal code of communication is what characters go back to when words are simply not enough; their inner conflicts bursting through the screen as the hypnotizing bouzouki melodies take over their body movements. Amidst the oppressive grasp of authoritative political and economic forces, these expressions remain uncompromising and free; a nonconforming safe haven that transcends aesthetic canons and social standings.

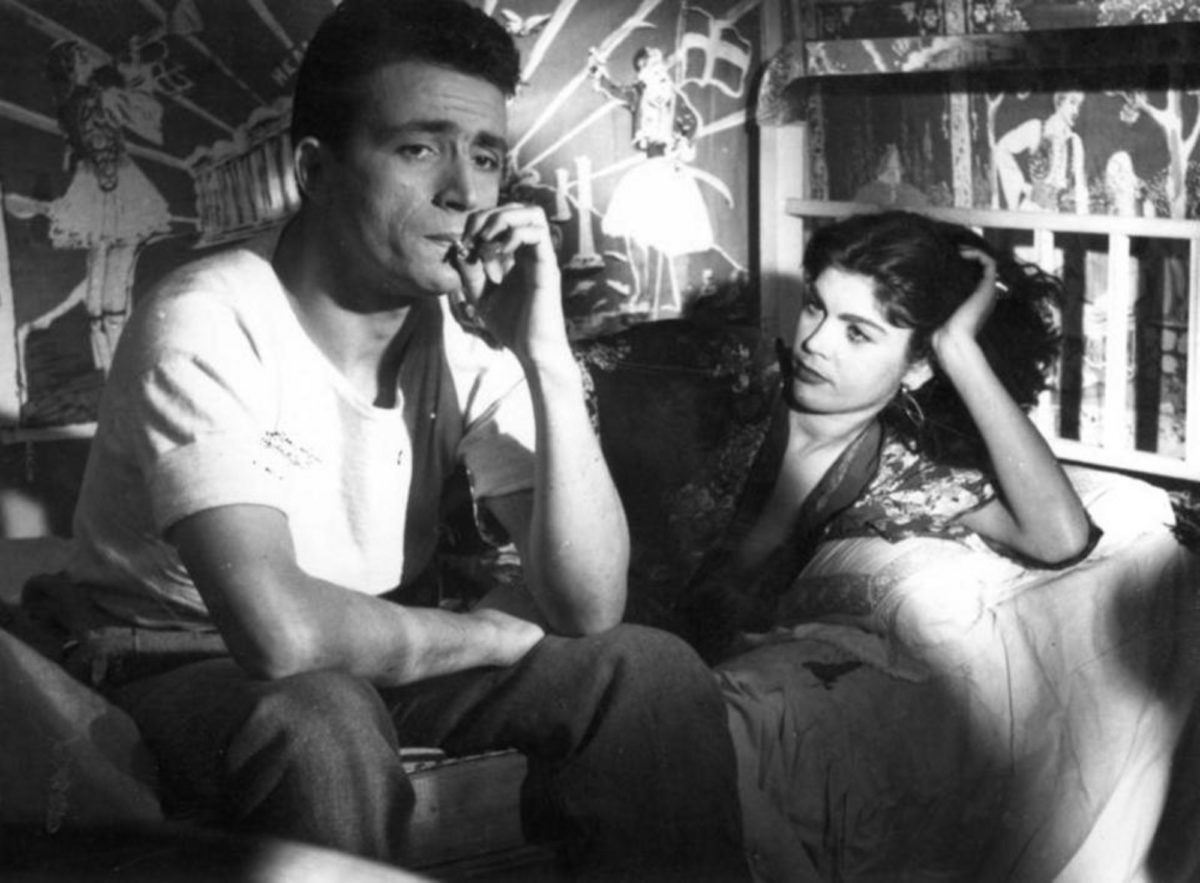

This can be traced back to Koundouros’s iconic debut, The Magic City (1954), in which he portrays the moral tale of a young man from the grubby slums of post-war Athens trying to make ends meet by any means necessary. Although a classically neorealist set-up on paper, the film is gradually enveloped by a genuine fascination for the murky aesthetics and narrative beats inherent to the metropolis’s underbelly. Soon enough, scenes of crowded dirt-roads and reluctant hard labor fade into the alluring glitz of neon signs and tropical orchestras. In his quest to climb the social ladder, protagonist Kosmas (George Foundas) finds a whole other side of Athens hiding in plain sight, one that only manifests itself once the sun goes down. This so-called magic city serves as a social melting pot of sorts; a place where those in dire economic need fall directly into the claws of others willing to offer a Faustian bargain. Kosmas is just another victim in this apparently never-ending cycle. Or so it seems at first.

Eventually, the money earned by smuggling begins to “burn his hands”, as he states, since the rugged machismo of life by the docks begins to lose its appeal in favor of the communal warmth irradiating Kosmas’s homely surroundings. Koundouros and screenwriter Margarita Lymberaki aren’t really aiming for subtlety in how they represent this moral contrast. From the shadowy contour casted over everyone in the dimly lit casino, to the frenetic rhythms of its rock ‘n’ roll soundtrack and the reproduction of traditional noir archetypes (the gown-wearing seductress, the stoic men, etc.), the narrative suddenly morphs into a pulpier affair. This new side of Kosmas’s life is framed in a bombastic style that directly opposes the more subdued tone of how his daily working-class existence is shown, a fact that underlines how the moral and physical dangers of street hustling progressively alienate the protagonist from those that really matter to him. Instead of following the traditionally nihilistic outlook of crime dramas, The Magic City sees beauty and redemption in the possibilities brought by collectivity. As the town rallies around Kosmas in the film’s climactic final scene, its reactionary position is fully established: a rejection of the corruption and vice brought upon by modernity that champions the perceived nobility of a humble and traditionally conservative way of life. To Koundouros, the formal contrast of the two paths Kosmas has to choose from represent the greater divide in Greek society at the time: a reluctant acceptance of the free-for-all Westernization of Athens, or an intimate resistance where communal collaboration is positioned as one of the last holds on a fading Greek identity.

The director’s follow-up, The Ogre of Athens (1956), expands on these topics while noticeably doubling down on its noir elements. Long gone is the black and white moral compass that guided The Magic City, replaced by a landscape fully engulfed by grayness and urban decay. The beacon of hope, previously embodied by the romanticization of a simpler way of life, now dwells on the crumbling spirit of an unsuspecting man called Thomas (Dinos Iliopoulos). In a truly Borgesian fashion, one day his dull life as a small-time bank clerk is forever shaken by the realization that his identity has been mistaken because of his resemblance with renowned crime lord “The Dragon”. What ensues after this arbitrary prank of destiny is a play on the canonical mistaken identity crime drama, where a usually rugged protagonist has to force his way out of an escalating situation. In Thomas’s case, his bookish looks help him avoid most confrontations by merely embracing the confusion, going through the motions and reluctantly ruling the underworld behind a stoic facade that conceals his characteristically frightful demeanor. Until his own character is put to test in the face of temptation, that is.

Koundouros and DoP Kostas Theodoridis portray the process of spiraling into darkness by pulling from the expressionistic aesthetic signifiers of 1940s crime thrillers, like those of Jules Dassin and Carol Reed, par exemple. Facial features barely standing out amidst all-encompassing shadows; rooms filtered through the dense smoke of cigarettes; enigmatic “dames” seeing through the facade of coolness… Each of these elements collides into an hyperbolic universe of social decay much in line with hard-boiled fiction, in which Thomas stumbles his way around until it all goes back to normal. But how could it really? How can a man simply forget the power he held, the fear he generated, and the respect he felt? For once in his life, Thomas can see beyond the limitations of his working-class wages and non-existent social status. He no longer needs to feel threatened, as he is feared immediately by everyone around him. He even has the power to transcend the sooty sights of the crumbling city that have littered his eyes ever since he was born. But, in exchange for all this, he has to give up his essence; everything about him and his relationship with this particular place and time cannot withstand this new modus vivendi.

Through its structure as an existential fable, The Ogre of Athens reflected on what was a very contemporary sense of post-war alienation. Unlike The Magic City, modern men, part of this barren moral wasteland, have no escape once they’re consumed by power. The separation between imported iconographies and local expressions (dance and music in this case) began to blur, meshing into an inescapable postmodern environment virtually unrecognizable from what was before; a corrupted setting where everyone is looking out for themselves, and there’s no safe haven to be had. And yet, once the enveloping thrill of the Dimotiki music’s crescendo reaches its peak intensity, the mind is washed over by primal emotion; a sudden remembrance that recalls who one really is.

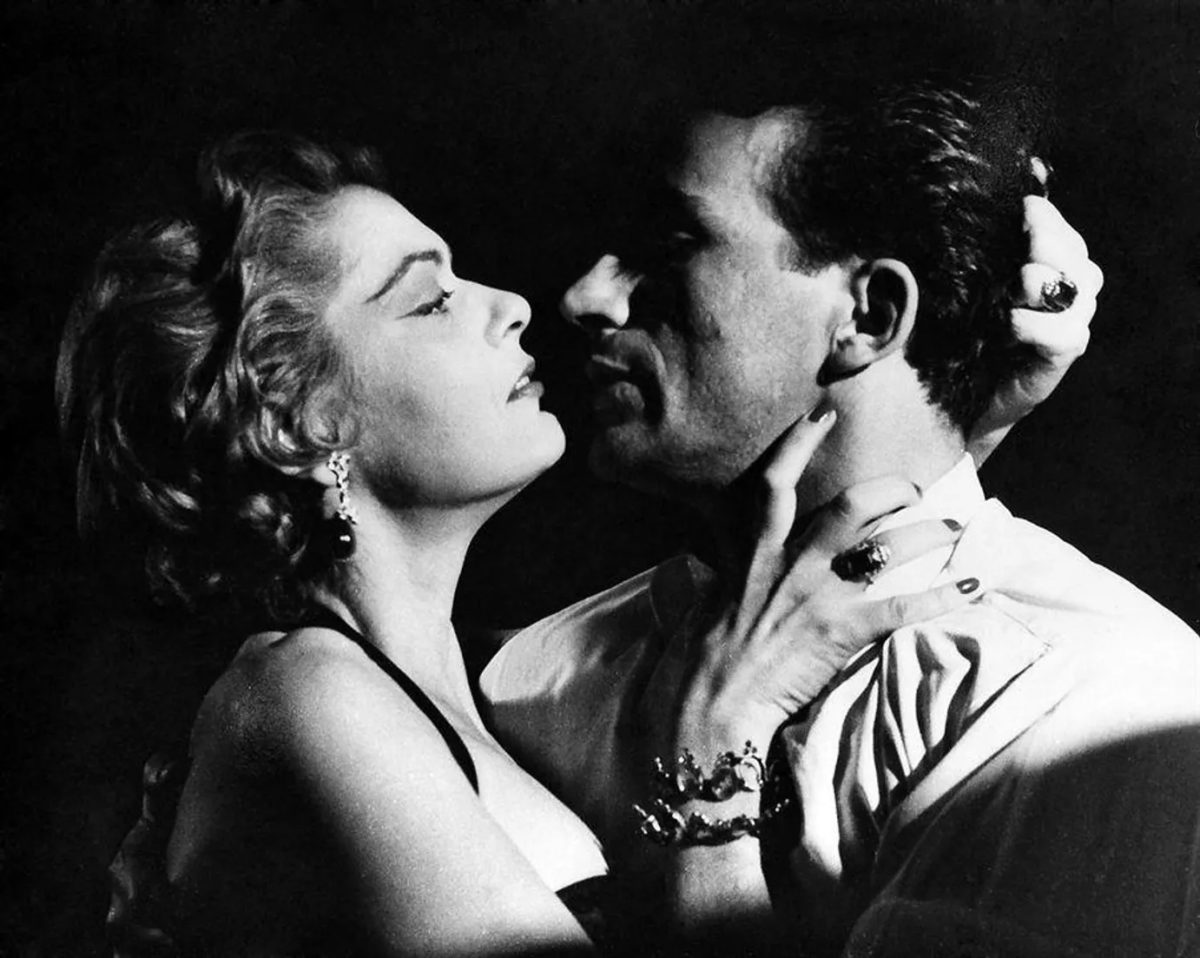

While Koundouros explored the existential tension emerging during the modernization of a recently devastated society through broad moral tales, the early works of Michael Cacoyannis brought a totally distinct outlook by focusing instead on the impact of cultural change on domestic life. Like Koundouros, Cacoyannis also brought external filmic references and recontextualized them to the specific social context of Greece at the time. In his case, melodramatic elements like ornate performances and a dramatic structure built around confrontations were toned down to fit as quintessential vessels for the intimate narratives about social stigma and fading traditions he favored during this period of his career. In Stella (1955), Cacoyannis’s breakthrough and what many consider the official start of the Golden Age of Greek Cinema due to the visibility brought by local controversy (even deemed vulgar by Greek film critic Antonis Moschovakis for its depiction of female independence) and its rapturous reception at Cannes, the story revolves around the titular protagonist (Melina Mercouri), a woman carelessly enjoying her life and sexuality, with little to no regard of the role a patriarchal society wants for her. In her daily routine at the local dancing saloon, she playfully lures any man that catches her fancy, no strings attached (at least for her). What she eventually finds out is the reluctance of men to actually grasp her way of living once she leaves their morning embrace and continues being herself outside of the tantalizing and festive environments. For the men in her life, it’s simply counterintuitive that a woman wouldn’t want to settle down, but in her self-determination, Stella seizes her own violent freedom.

In a surprisingly acute indictment of machismo for the time, Cacoyannis and screenwriter (and playwright of Stella with the Red Gloves, the play Stella is inspired by) Iakovos Kabanellis showcase how fragile male idealization is when confronted with female empowerment. To the array of men Stella meets, the cliched ideal of a relationship built on casual sexual encounters crumbles when they realize their actual powerlessness over her. Akin to the elated dance sequences and enthralling score of Koundouros’s The Ogre of Athens, an underlying musical component guides the emotional arc to its most climactic moments: bodies swinging in tandem to the traditional beats of Greek music, tense looks dripping with longing and melancholy, a primal catharsis emerging from the collective frenzy of the swift Dimotiki rhythms… “A mirror into the soul of Greek people” as one of these parties’ taglines announces in one of Stella’s opening scenes—a preamble that materializes when Stella herself lets everything out via song in one of the film’s most enthralling sequences. After all, even if her narrative arc mirrors the mounting tension inherent to melodrama, her struggle is not one guided by tangible external forces exerting themselves.

Just like Mercouri’s performance as Stella, Ellie Lambaetti’s Chloe in Cacoyannis’s A Matter of Dignity (1958) has a presence that the director can’t contain within the frame. As in his scandalous breakthrough, he works with his leading figure to create an overpowering dramatic garishness in which each of Chloe’s body motions suggest shades of melancholy. For the character, these are discrete bursts of acknowledgement of the conflicting notion of her whole persona being a farce; merely a vestige of a social standing that she can no longer embody accurately due to the bankruptcy of her familial state. But, that’s the only life she’s ever known, so she keeps holding on to it no matter how desperate the situation becomes.

In some ways, A Matter of Dignity exists as a companion piece to The Magic City, as a captivating semi-neorealist take on the economic hardships of early post-war Greece, just that in this case it flips the perspective. The urgency of Kosmas’s struggle came from a place of need, a candid belief in the promise of social advancement through material means. Conversely, Chloe sees her privilege steadily collapse, which binds her to the uncomfortable requirements of saving face in aristocratic circles. In Koundouros’s films, Athens’s scrappy underworld of vice and excess exists as a hyper-stylized noir universe, mirroring the expectations of those seduced by it. Cleverly, Cacoyannis takes the reverse approach in A Matter of Dignity. It’s Chloe’s first encounters with working-class reality that are showcased expressively. The soundscapes of the slums and public transportation washing over everything else, the rugged visages intercutting rapidly, the frantic camera movements… Like his protagonist, Cacoyannis manages to represent this social context with a genuine sense of wonder and excitement; a feeling that permeates the film’s final take on redemption and liberation, and that recontextualizes the classic melodramatic fall from grace within a wider and richer societal grounding.

Like most Greek citizens in the post-war period, Chloe sees her previous way of life crumbling in front of her eyes; an unstoppable process that puts into question her very essence, without leaving any time for gradual realizations or transitional periods. As experienced, sudden change feels like a hecatomb: a rude awakening that eventually overcomes any intent of self-denial and rationalization, and has to be faced upfront, whatever the consequences.

———

As these narratives have shown, the ways in which these two directors personify Greece’s post-war introspection come from an unapologetic acceptance of cinematic genre traditions. Despite effectively portraying a breathing, working-class environment, the need for pathos as an expressive method is something that eventually takes over; emotion bursting to the forefront one way or another, be it through the impressionist close-ups of Cacoyannis’s protagonists, or Koundouros’s expressionist use of lightning and decor. Martyrdom, communal upheaval, death… The finale in each of Koundouros’s and Cacoyannis’s films depicts a possible outcome for the concerns of Greek society between periods of subjugation and overwhelming uncertainty; different paths in a constant search for individual liberty and collective self-determination. Their embrace of cinematic hyperbole is in many ways essential to the understanding of their conceptual undertakings. These were popular and populist films that never felt above engaging audiences earnestly—sharing their fears, mirroring their desires, and putting forth the imagined possibilities of what their futures might hold—their heterogeneous versions of Athens going beyond a unified national identity, freeing themselves from stylistic tropes and cultural expectations, and fully embracing the erratic recollection of subjectivities that has marked this polarized nation ever since.