If you’re planning a trip to Paris, be sure to catch the wonderful exhibit Le Monde enchanté de Jacques Demy at the Cinémathèque Française (it runs until August 4; for more info see the Cinémathèque’s website). The exhibit manages to capture both the charm and intelligence of Demy the man and the mood of his films, constantly hovering between fantasy and the (hyper)real, between romance and (social-political) disillusionment, joy and sorrow.

One of the aims of the exhibition—and the accompanying retrospective of his 13 feature films and handful of shorts—is to restore Demy to the historiography of French cinema, that of the nouvelle vague in particular. All too often, Demy has been critically undervalued because of his commitment to a “self-contained fantasy world” (this is from the Wiki entry on Demy which Jonathan Rosenbaum tears to shreds here). Agnès Varda, who married Demy in 1962 and who has probably done most to preserve his legacy, provides the best description of Demy’s seriousness as an artist: “Sentiments sérieux aux racines profondes et fleurs si légères qu’on dirait des flocons de neige ensoleillée.”’ Le Monde enchanté de Jacques Demy invokes Demy’s serious side by devoting its centerpiece to Model Shop (1969), the film he made after moving to Los Angeles with Varda in 1969, a city whose everyday life and architecture Demy believed had never been done justice in the movies. Model Shop was misunderstood at the time of its release as much because of its view of the counterculture as because of a documentary realism that, although Demy had trained as a documentarist, came as a total surprise from the maker of Les Parapluies de Cherbourg (1964) and Les Demoiselles de Rochefort (1967). In the exhibition, a video interview with a wistful Harrison Ford, who made his debut in the movie and, in a way, was discovered by Demy, is what provides these serious sentiments with some “light flowers.”

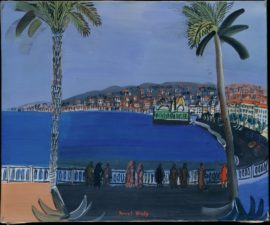

The seriousness of Demy’s artistry is demonstrated by presenting the overview of his life and films as what the curators call a “palimpsest” of recurring characters and situations, and by framing this lifework with the artists who influenced it. Cocteau—whose lifelong reworking of the Orpheus myth resonates in Peau d’Âne (1970) and in the late Parking (1985)—features prominently, as do artists like David Hockney, the surrealist Leonor Fini, Gustave Doré (an influence on the fairytale world of Peau d’Âne) and the fauvist Raoul Dufy, whose series of aquarelles La Baie des Anges inspired some of the shots in the eponymous, recently restored film.

The spectacular opening scene from La Baie des Anges (1963)—a movie I had never seen—starts on an iris-out followed by a wild, Ophülsian tracking shot along the Promenade des Anglais, as if picking up where Lola (1961), itself a circular narrative that ends on an iris out, left off. (In Model Shop the connection between Lola and La Baie Des Anges will be further established.) The scene is featured in the exhibition on a video monitor and—more than the set photos from the movie featuring Jeanne Moreau in a Marilyn-like peroxide wig—urged me to watch it as soon as I got back. La Baie des Anges did not disappoint: in many ways it is the clearest elaboration of Demy’s oscillation between documentary realism—manifested primarily as the portrait of a (coastal) town, be it his native Nantes, the hyper-real Cherbourg or Nantes of his musicals or, in the case of La Baie des Anges, Nice and Monte Carlo, and their particular neighborhoods and hangouts—and fantasy elements that are primarily expressive of a kind of romantic/existential longing. More unexpected was the way ritual here translates into Dostoyevskian metaphysics, a “seriousness” that demands an austerity of form that at times feels completely opposite to that opening shot and to the earlier Lola’s swooning crane shots, a preference for extreme mobility of the camera that will resurface with even more expressive power in Parapluies and Demoiselles. The formal constraint and control on display in La Baie des Anges—a control that extends both to the drily modulated performances, the sparse but highly effective use of Michel Legrand’s score and a fleeting final shot that is such an indelible testimony to love triumphant precisely because of its brevity, because of the severity of the cut—aligns the film most closely with another important influence, that of Robert Bresson.

A Purity of Style

Bresson is much less visible than Cocteau in the Cinémathèque exhibit; there’s a good chance the casual visitor will miss the small quote from Varda on Pickpocket (Bresson, 1959) amid the primary-colored splendor of the recreated sets from Parapluies and Demoiselles or the heat cast off by the bodice worn by Anouk Aimé in Lola: “When I met Jacquot in 1957, he’d seen Bresson’s Pickpocket three times. We went to see it four more times.” Next to the bodice, there’s a picture from Elina Labourdette in Les Dames du Bois de Boulogne (Bresson, 1945; with dialogue by Cocteau) that was used in Lola, as was Labourdette herself and her bare-legged eroticism, accompanied by a comment from Demy that Les Dames was his formative film-going experience as a child. The influence of Bresson in La Baie des Anges is most visible at a thematic level—chance, skill, risk, loneliness, addiction, ritual and the moral power of intuition are all familiar beats from Pickpocket—and from the performances. Although Jeanne Moreau and her wig steal the movie (“What would this film be like without Jeanne Moreau?” life-long devotee Pauline Kael wondered in her short review of the film: “The picture is almost an emanation of Moreau”), Claude Mann’s performance is arguably the more important. Mann, who would be so good in Melville’s L’Armée des ombres (1969), plays the part of a young bank clerk, an everyman called Jean Fournier, who throws caution to the wind and embarks on a gambling spree with Moreau’s ludophile Jackie along the Riviera. Mann’s extremely restrained performance is staged as if dramatized by an actual bank clerk: his delivery is intentionally flat and affectless (“flattened by life,” Bresson would say) even at the most melodramatic moments, of which there are many in the script, adhering to Bresson’s lesson that film acting can never be about portraying or projecting scripted emotions. Mann, physically similar to both François Leterrier from Un condamné à mort s’est échappé (Bresson, 1956) and Martin LaSalle from Pickpocket, gets several big close-ups in the film but his inexpressiveness, approaching the blankness of the “Bresson face,” turns him into a tabula rasa for the audience to inscribe; it is only by observing him perform small, uninflected almost instinctual actions—pouring Jackie a scotch, shuffling his casino chips—that something of his character shines through (“still and watchful as a croupier,” is David Thomson’s evocation in his Dictionary). Pauline Kael is right when she writes that La Baie des Anges is an attempt to “purify,” to “get to the essence” of something. Unfortunately, she then ties this insight to Moreau’s performance only, aligning her with kindred self-performers like Bette Davis and Constance Bennett. Which brings us back to Kael’s observation that the movie is inconceivable without Moreau, even if, she grants, Demy displays “a virtuoso sense of film rhythm.” And “rhythm” is what Demy is trying to purify here; in a sense you could argue that he couldn’t have made a musical as unforgettable as Parapluies without the lessons in (Bressonian) rhythm learnt from La Baie des Anges. Repetitive rhythmic editing structures are at the heart of Bresson’s style, and Demy employs a similar patterning of both action, setting (like Pickpocket this is a festival of comings and goings between room and “work space”) and camera set-ups in a film that is structured around extremely similar sequences taking place at the roulette table. Changing money, for instance, is a recurring action that is presented as an almost ritualistic practice. Demy repeats these essentially superfluous scenes throughout the picture, at every point making sure that he varies the camera angle but that the sign (symbolically) announcing “CHANGE” remains visible in the frame.

Bresson vs Pudovkin

Bresson’s influence on the nouvelle vague is widely acknowledged: Bresson was one of an elite band of French directors who found grace in the eyes of the Truffaut of ‘Une certaine tendence’, next to Renoir, Tati, Melville and Varda. In ‘La Caméra-stylo’, Astruc posits Les Dames du Bois de Boulogne as “establishing the foundations of a new future for the cinema.” Still, the precise nature of that influence remains understudied. Of those new-wave directors whose style was shaped by Bresson’s ideas on performance, framing and editing, Godard and Demy are key: like La Baie des Anges, Godard’s Vivre sa Vie (1962) is indebted to Bresson’s fronting of episodic structure, parallelism and variation. And like Godard, Demy is enamored of tight, straight-on framings in the manner of Bresson. Unlike Godard, however, Demy seems relatively uninterested in exploring the parallels between Bresson’s theories of editing and those of Eisenstein and Pudovkin. Like the Soviets, Bresson believes in eliminating “distraction” from the filmic representation, keeping the mise en scène sparse to heighten the expression of the relevant detail. The only difference is that in Soviet cinema that “detail” is mostly made emblematic of ideological expression, whereas in Bresson it expresses a spiritual core of meaning. Let’s compare Pudovkin’s description of the process of filmic construction of space and time to a repeated/varied five-shot sequence from Un condamné à mort (I take the shot descriptions from Doug Tomlinson’s essay on Bresson’s “aesthetics of denial”). In On Film Technique, Pudovkin elaborates how editing eliminates the need for a coherent pro-filmic space: “By the junction of the separate pieces the filmmaker builds a filmic space entirely his own.” The hypothetical example he gives as illustration is that of a man falling from a window five stories high:

In order to show on the screen the fall of a man from a window five stories high, the shots can be taken in the following way:

First the man is shot falling from the window into a net, in such a way that the net is not visible on the screen; then the same man is shot falling from a slight height to the ground. Joined together, the two shots give in projection the desired impression. The catastrophic fall never occurs in reality, it occurs only on the screen, and is the resultant of two pieces of celluloid joined together. From the event of a real, actual fall of a person from an appalling height, two points only are selected: the beginning of the fall and its end. The intervening passage through the air is eliminated.

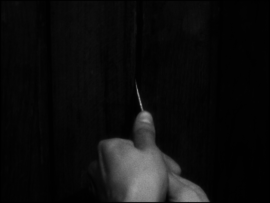

In this scene from Un condamné à mort, the prisoner Fontaine tries to release the panels of his cell doors:

I have left out the striking sonic design of the scene and the intrusion of the voice-over, flatly and redundantly rehearsing the simple acts we are shown, because I want to emphasize what this sequence shares with Pudovkin’s montage: the lack of an overall view or establishing shot. All we get are partial views and a unified space exists only for the viewer to infer. This is totally opposite to classical Hollywood practice and the conventions of analytical editing, where it is customary to start from a full shot laying out the dramatic space and the respective positions of the players, before analyzing it, breaking it down into separate closer shots matched by eyelines and generally adhering to a 180° perimeter or “axis of action.” Bresson never went so far as to ask his viewers to unify spaces in physically impossible ways, as in Kuleshov’s Engineer Prite’s Project (1918) or Mr. West (1924). His goal, like Pudovkin’s, is not relativism or irony but to highlight the detail—be it gesture, face, or object, or performance in general—by abstracting it from a recognizably “real” background. Pudovkin called the construction of a purely cinematic space and time “constructive editing.” In an enlightening video essay posted here, David Bordwell explains the principle of constructive editing by looking, precisely, at an example from Pickpocket (he also illustrates Pudovkin’s principles with a scene from The End of St. Petersburg [Pudovkin, 1927]), in which Bresson constructs the action—Michel attempting his first theft by taking the watch of a man crossing a busy street—from single shots, withholding an orienting view. Although, in Les Demoiselles de Rochefort, Demy set up a system of straight-on 180° reverse cuts in some conversation scenes between twin sisters Deneuve and Dorléac, he never elides the establishing shot. The reason might be that he’s simply too enamored of the camera crane sweeping in at the beginning of the scene, revealing locale like a stage set, to follow Bresson in this constructivist part of his aesthetic.

Constructive Editing and Intensified Continuity

To conclude, let’s take a brief look at the function of constructive editing in today’s commercial filmmaking. Bresson’s editing often favors prolongation of a moment or delay of a response, but contemporary instances of constructive editing that occasionally pop up in Hollywood cinema, seem to take their tempo from the “shocks” and accelerations of Soviet cinema. In The Way Hollywood Tells It, Bordwell has argued that the intensified continuity style of contemporary filmmaking has adapted the principles of Kuleshov and Pudovkin by building dialogue scenes out of brief shots, using fewer establishing shots, thereby eliminating a perceived “redundancy” that is particularly salient in these times of increased visual literacy. Today’s Hollywood directors shoot a lot of coverage, often using several cameras, so there may be many alternative versions available during editing. Asked about his assembly cut for his recent Side Effects (2013), Steven Soderbergh explains that “there was one scene that ended up getting cut significantly, I’m only using the front part of it now, in Side Effects where it was a long dialogue scene that I wanted to play out in one shot… A lot of it though what you would find is scenes that I just, like I said, I cut the entire back 2/3 off or I cut the entire front 2/3 off. There was a lot of hacking, just like, literally I don’t need the first 2/3 of that scene, I can just come in on that line. There was a lot of that in the last edit I did.” (You can find the interview with Soderbergh here.) Like most of his peers working in the intensified continuity style, Soderbergh is fond of a fast cutting pace and discontinuous editing effects like jump cuts, adding to these deliberate crossings of the 180° axis for effect. As the following example from Contagion (2011) shows, intensified continuity isn’t just a matter of “hacking,” of chopping up or trimming longer sequences. Sometimes the establishing shot does make an appearance but is withheld until the end of the scene. The scene, in which researchers at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention discuss an unknown disease being a mix of genetic material from pig and bat viruses, is built up extremely simply, moving back and forth between the doctors and the display showing the viral strand they are studying. The scene starts in medias res with a wide-angle medium two-shot of the two researchers (Jennifer Ehle and Laurence Fishburne); the space is not laid out in its entirety beforehand, so eyelines, camera angle and body orientations are assumed to do the spatial cueing we need. After repeating a reverse-angle cutting pattern, Soderbergh gives us an unexpected establishing shot from an oblique angle: when Fishburne has got up and left the space, the perspective shifts to outside their cubicle, matching the abstract cluster of viral DNA seen on the monitor to the impersonal grid of the CDC’s bureaucratic architecture.

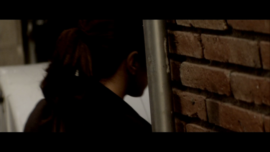

In Contagion the establishing shot is often elided in function of narrative that is constructed—as is typical for Soderberg—of an intricate series of interlinking and interacting plot lines. Transition between these scenes, structured around a pressing deadline, is often a function of a what Bordwell and Thompson call a “dangling clause,” a causal chain that’s left unresolved in one scene, or a “hook,” linking a specific causal element of the end of one scene to that at the very start of the next. In Soderbergh’s case the dangling clauses are often temporally fragmented: exposition in what is essentially a pretty straightforward genre exercise like Haywire (Soderbergh, 2011) is relatively confusing because he edits the classical talking heads—the director of the security firm (Ewan McGregor), a government agent (Michael Douglas) and the agent’s Spanish contact (Antonio Banderas)—laying out the action and introducing the plot’s objective and deadline, with images that we are asked to recognize as flashbacks and, through crosscutting, with action we are meant to read as happening simultaneously. Images hooking to images or sounds, whose narrative progression is either temporally continuous or discontinuous, possibly via actual match cuts, logically are less inclined to orienting views. Soderbergh—influenced by new wave filmmakers like Godard and Resnais or, by proxy, Richard Lester and the John Boorman of Point Blank (1967)—is a meticulous craftsman with a distinct feeling for cinematic rhythm, whose approach is the complete opposite of the run-and-grab style of filmmaking that typifies much of today’s commercial filmmaking. The following series of shots from one of several set pieces in Haywire shows how you can intensify the action of the scene through constructive editing. In the scene, security agent Mallory (Gina Carrano) and her team prepare to free a Chinese dissident held hostage in an apartment in Barcelona. The first shot is a de-centered view of Aaron (Channing Tatum), the agent who is on lookout in the car. Soderbergh then cuts 90° to the side of the car, revealing another operative next to Aaron. Their eyelines more or less connect the shot to the following view of a third agent outside the car and on the phone. The phone hooks into the next shot, a tilted angle on Mallory, de-centered like the first shot in the sequence, listening in through her earpiece. The low angle on Mallory matches our view of the third operative looking up, turning this shot into an actual POV.

The following cut is to a view of a man we have to infer is guarding the apartment. Soderbergh makes this hypothesis accessible by replaying the guard’s exiting from the same camera angle but this time in black and white and in slow motion, suggesting both spy cam footage and a heightened sense of alertness on the part of the operatives. These two shots of the guard at first glance do not appear to be matched to anyone’s eyeline, but if we look at the blurred dark border at the top of the frame we can infer that these views are seen from inside the car. This inference is again confirmed by the next shot, a repeat of our first image, with Aaron now moving his lips without the viewer hearing what he says. The next shot, back to the man on the phone, suggests that Aaron is communicating with him from the car and is therefore the one steering the operation.

The next shot, like the two shots of Mallory that follow and the next two shots of the third operative, is another example of a deliberate mistake against the 180° axis that serves as a flourish or “beat.”

Again, because the establishing shot is withheld, the relative position of the characters is unclear perhaps, but not confusing. Throughout the sequence we have no idea where these characters are in relation to the apartment building. This becomes clear only when they actually move inside the building.

Continuity throughout this sequence is held by the eyelines, body orientations and, most of all, by the redundancy of the situation: minimal cues suffice to infer a spatial whole or locale, freeing the attention to focus on the expressions of character in the close-ups. So, you could argue, Soderbergh’s use of constructive editing principles to steer the viewer’s attention to salient details and expression of character is not so far removed from the Bressonian deconstruction of space. The only difference is that, like Demy, he is being serious in an art of light flowers.