Lets take another look at that quotation from Jacques Rivette on Howard Hawks, cited in my previous report:

“There seems to be a law behind Hawks’s action and editing, but it is a biological law like that governing any living being: each shot has a functional beauty, like a neck or an ankle. The smooth, orderly succession of shots has a rhythm like the pulsing of blood, and the whole film is like a beautiful body, kept alive by deep, resilient breathing.”

The biological metaphor Rivette has devised to discuss the beautiful order and efficiency of classical Hollywood editing patterns, is a variation on the geological metaphor introduced by André Bazin when making a similar point about the “classical perfection” of French and American talkies: “By 1939 the cinema had arrived at what geographers call the equilibrium profile of a river … the river flows effortlessly from its source to its mouth without further deepening of its bed.” A “geological shift” would then occur with Welles and Toland’s use of deep focus, combining the analytical capabilities of continuity editing with the openness of the (pre-classical) tableau style to provide a “dialectical step forward” in the stylistic development of cinema.

It is commonly assumed that by about 1917, most of the elements of continuity editing were in place. And it is certainly true that American movies of the period – tightly scripted, smoothly staged and cut, with the acting generally obeying the “verisimilar” code – look light years ahead of most of their European competitors in terms of efficient storytelling strategies. (When the Cinema Ritrovato screened Straight Shooting from 1917 as part of their John Ford retrospective in 2011, David Bordwell mused afterwards that the European filmmakers who saw this type of American import must have recognized defeat: “Well, it’s all over!”) What is less clear is which studio or directors were instrumental in refining principles of “invisible” continuity editing, moving away from Griffith’s emphasis on crosscutting and contiguity editing (moving from one space to the adjacent one while matching action between the shots; although by The New York Hat and The Mothering Heart of 1912-13, it seems D.W. was in on the game) towards a more analytical model based on cut-ins, variegated and reverse angles and eye-line matches. As with many other aspects of cinematic style, notably set design, photography and acting, it seems Vitagraph was slightly ahead of the rest: Barry Salt has argued for Ralph Ince as a major figure in the development of continuity editing (specifically his use of reverse-angle cutting), more important than DeMille at Paramount or Reginald Barker at Ince-Triangle. Given that Raoul Walsh is fêted at this year’s Cinema Ritrovato, I would like to plead the case of Regeneration (1915) as a milestone in American cinematic storytelling. As David Bordwell notes, Regeneration’s “brief scenes, rapid cutting, and constant changes of angle probably seemed as frenetic in 1915 as any action movie looks to us today.” Let’s put it to the test and look at a fairly simple and straightforward scene early on in the movie, in which the story’s young hero, Owen, an orphan forced to live on the street takes up the defense of a hunchbacked street urchin harassed by vagrants hanging out at the docks.

Fig. 5 Cut back to Owen whose eye-line is also matched to the view in the previous shot (the bums are off-screen right so everyone’s position is established now).

Fig. 6 The boy answers the bums calling from off-screen right and exits the frame in that direction.

Fig. 7 We see him entering the frame from the left (the right screen direction is maintained), while the angle of the shot is the same as that in fig. 5 (notice how, in fig. 5, a space was left for the boy to occupy).

Fig. 8 Again we cut back to Owen, this time in medium close-up, establishing him as the onlooker.

Fig. 9 Owen’s eye-line is matched to the same set-up as in the previous shots with the bums, who now start harassing the boy.

Fig. 11 Owen and the boy have indeed switched places: the boy is now the onlooker, occasioning a new series of eye-line matches…

The basic principle is recognizable from many American movies of the mid-teens. In the William S. Hart western, The Return of Draw Egan (1916), for instance, the convention is established of bad men luring at each other in a saloon through superb play with eye-lines.

Fig. 2 … because we now get a cut-in to the gent in medium close-up, checking out Bill.

Fig. 3 That he is looking at Bill, is established in the next shot of our hero pouring himself a drink, matched to the stranger’s eye-line…

Fig. 5 Things become more interesting when six rough-looking gents join in the fun (notice how we get that the guy in the middle is their leader merely from his stance and relatively central position in the shot).

Fig. 6 It’s hard to determine who’s looking at who now, since we have ourselves a staring contest structured around intersecting eye-lines…

Although Hart’s mise-en-scène and cutting were hugely influential (John Ford would make an almost exact copy of this scene in Straight Shooting), Walsh’s film is even more dynamic and fast-cut, varying the angles on the action and increasing the number of eye-lines by rounding up a superb troupe of extras (including a wart-nosed onlooker who gets an irised close-up and appears to be the first in a series of “nose comedians” in Walsh, the most prominent of which is Sammy Cohen). The whole sequence is over in little more than a minute and counts 22 shots, bringing the average shot length to about 3 seconds. The average shot length of the movie overall is 4.5 seconds, which is a frenetic pace rivaled only at the time by the short Keystone comedies.

Kindred of the Dust (1922, one of the few extant Walsh films from the early twenties which also screened in Bologna), made independently for Walsh’s production company as a starring vehicle for his then-wife Miriam Cooper, seems slow and “old-fashioned” compared to the cracking Regeneration, this despite an exciting fight between the hero (Ralph Graves) and the slum-dwellers who have been harassing his sweetheart Nan (Cooper) for having a baby out of wedlock, which harks back to the earlier film in its fast cutting and rough realism. But the rest of the movie is a late variation on the Griffith pastoral (the book is by über-sentimentalist Peter B. Kyne) and also looks ahead to what would become (despite the often brilliant cutting of the movies Ford made for the studio) the Fox house style: long-ish shots that heighten both the softly melancholic mood of many of these films and the arty photography and deep-space set design, in this case by Maurice Tourneur’s cameraman Charles Van Enger and William Cameron Menzies.

The same logic, in my view, applies to another Menzies-designed picture made by Walsh as a prestige assignment at United Artists: The Thief of Bagdad (1924). Despite Doug Fairbanks, this excessively long and narratively unbalanced epic (the first part serving to introduce the characters and set up the plot is longer than the actual quest that follows!), lacks energy and as a movie is inferior to Regeneration, despite the brilliant scenography. Since I have seen none of the films (all of which are extant) betweenThief and What Price Glory (1926), I have no way of charting Walsh’s evolution and of ascertaining whether the manic energy of the latter movie is to be credited primarily to the vigorous source material by Laurence Stallings and Maxwell Anderson, endlessly recycled but never bettered (the best variation is Hawks’ A Girl in Every Port from 1928). For a movie based on a play built around the constant banter of two U.S. Marines, Sergeants Flagg and Quirt (Victor McLaglen and Edmund Lowe in career-starting performances), stationed in France during the First World War, there are surprisingly little titles (“Here’s to your health. I hope it’s bad!” is one of the more memorable) Most of the boyish vulgarity that made the Stallings-Anderson play such a hit (that and the devil-may-care attitude it presents to a conflict overly dramatized in American fiction of the period) is conveyed visually, through the actors inviting us to lip-read their insults, and through the frenetic pace that makes a two-hour-plus movie whizz by, despite there not being any plot to speak of – as in most of Walsh’s movies from the early sound period – and jokes get extended way past their expiration date (this is the kind of movie in which McLaglen spits at a monkey). The way the movie starts is typical of what follows: McLaglen and Lowe’s attraction to American “showgirl” Shanghai Mabel (Sennett alumna Phyllis Haver) while stationed in Peking, is rendered as a symphony of low-angle shots on Mabel’s legs and behind. But other than this side to Walsh, there is the visual mastery: the way Walsh shoots feet only to suggest a romantic encounter, brings to mind Gaston Ravel and Jacques Feyder’s experimental Des Pieds et des Mains (1915), or, even earlier, a short American movie noticed by Jean Mitry called Over the Chafing Dish (1911) (see here). As Robert Keser points out in his insightful piece on What Price Glory, “It’s a sign of Walsh’s economy that a single shot of Quirt’s legs enclosing Shanghai Mabel’s ankles unmistakably signals their carnal familiarity.” Bazin would have sniffed at the vulgarity, but he would have appreciated the functional beauty. That same functional beauty is amply on display in one of Walsh’s best late silents, Sadie Thompson (1928), kindred in the rambunctious spirit of its first reels to What Price, although it came with a higher literary pedigree (the original story is by W. Somerset Maugham) and is accordingly more interested in its themes and moral message. In the movie Gloria Swanson performs another dry run for Sternberg-Furthman’s later Marlene archetype, the fallen woman with a shady past docking in an exotic location (Pago Pago on the island of Tutuila) and disturbing its natural order. In the scene I want to conclude with, Sadie enjoys a quiet moment with her beau, Sergeant Timothy O’Hara (played by Walsh himself) at her boarding house, Trader Horn, where they look at the Sergeant’s scrapbook. The staging and cutting in the scene is perfect (the editing is by Ince’s steady writer C. Gardner Sullivan), a master-class in classical Hollywood continuity style, giving us insight into Sadie’s mounting unrest and her growing attraction to O’Hara:

Fig. 6 … a medium shot of Sadie, taking from a slightly higher angle insinuating O’Hara’s standing position. As Sadie says, “Sit down, handsome – I ain’t a reviewing stand!” there is another match to…

Fig. 7 … another medium two-shot with the angle changed to a more sideways view of Sadie over O’Hara’s shoulder.

Fig. 8 Slight reframing puts them both at the dead center of the shot.

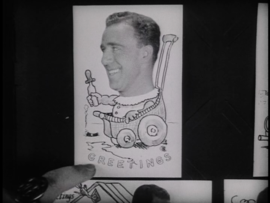

Fig. 9 A comic insert of one of the scrap book’s souvenirs, hides a cut-in to…

Fig. 10 … our closest view so far.

Fig. 11 Sadie turning away from O’Hara produces a match-on-action back to the master shot.

Fig. 12 After a beat we see why Sadie has turned away: Mrs. Davidson has entered with a friend. On Sadie turning her head there is a match to…

Fig. 13 … the first single (medium) close-up, allowing us to gauge Sadie’s disquietude: “Davidson can’t send me back to ‘Frisco, can he?”

Fig. 15 Back to Sadie, whose attention is drawn again to the scrapbook. As she moves closer to O’Hara there is match-on-action to…

Fig. 16 … our first (medium) close-up two-shot. Slight reframing restores the balance to the frame.