The pristine restoration of Chantal Akerman’s Jeanne Dielman, 23, quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles (1975) made me glimpse a detail I hadn’t noticed before. A freeze frame allowed me to recognize the cover of the book that Jeanne’s son, Sylvain, is reading. It’s a piece of trivia I haven’t found mentioned anywhere in the extensive writings on the film. Actually, the book is more than an ordinary prop since the boy is really absorbed in the work and seizes every opportunity to continue his reading: during dinner (“do not read at the table”); as soon as his homework is finished; or in bed before going to sleep. It might even be a more significant text than that other literary source, Charles Baudelaire’s L’Ennemi (1857), which Sylvain recites and that grabs more attention because it’s delivered in a one-time-only angle on the living room. The book he’s more quietly reading is Erik of het klein insectenboek (1941), translated into English in 1994 as Eric in the Land of the InsectsThe first French edition of the novel only appeared in 2006, which means the book wasn’t available in Akerman’s native language at the time.. It’s a Dutch children’s classic and the most famous and acclaimed novel by Godfried Bomans.

I asked theatre director Jan Decorte, who played Sylvain, if he remembered what book he was reading in the film. He didn’t. When I told him the title, he couldn’t recall how this book ended up on the set or if it was of any special importance to Akerman. So, what are we to do with the almost invisible, hidden, mysterious presence of this object or story within the film?

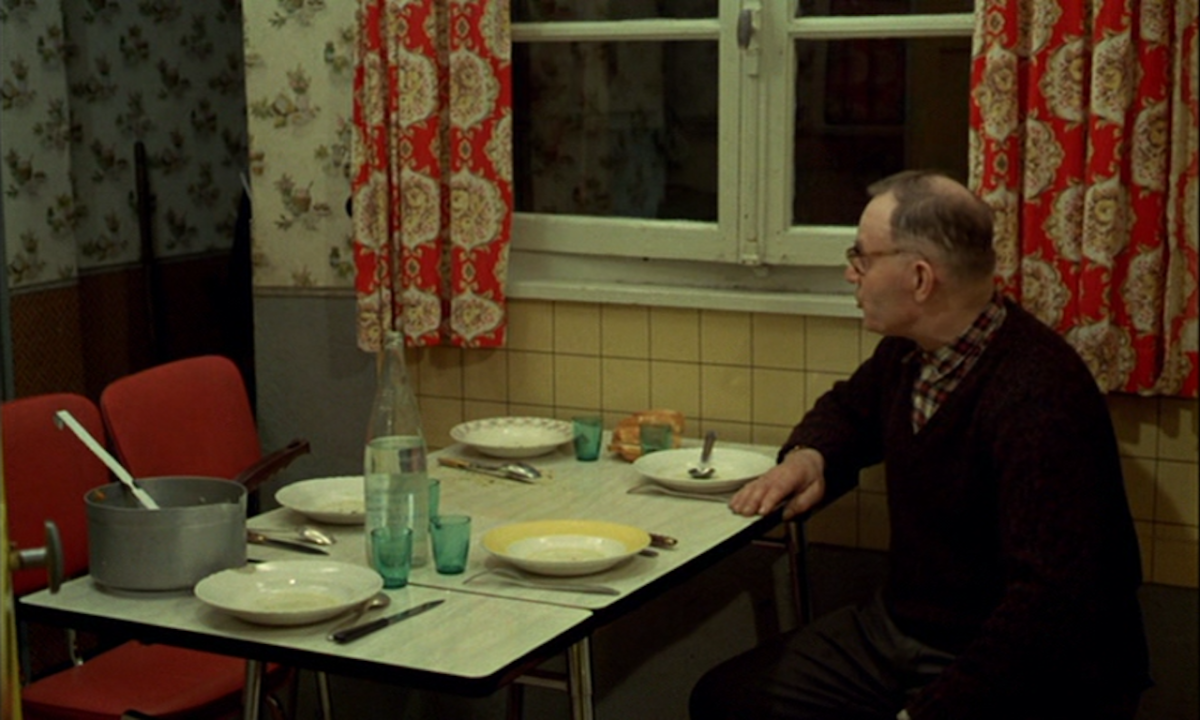

It would be easy to make narrative connections between the book and the film. The novel is about a boy, Eric Pinksterblom, who can’t sleep at night. Similarly, Sylvain is plagued by what in German is so wonderfully called Kopfkino. All the questions that have taken shape in his mind throughout the day emerge during the two bedtime scenes, the only times in the film that actual conversations with non-automated questions and answers develop. Likewise, in the book the paintings of Eric’s grandparents, hanging on his flower-printed bedroom wall, start to talk at night. Eric soon finds himself inside a pastoral landscape painting, where he meets with various insects over a series of meals. As in the film, some attention goes to the preparation of the food. (After some time, Eric longs for regular potatoes and the slices of bread in his school lunchbox.) While Eric is shrunken into the painting, Sylvain seems both too small and too big in the sweaters knit by his mother, which he “likes long” and tries on book in hand. Even Jeanne’s journey to replace Sylvain’s missing button is mirrored in the book, when Eric loses a button on the third day of his quest to look for the picture frame to escape out of the painting, something in which he ultimately succeeds.

In the end, Eric Pinksterblom learns that the insects are not so different from humans. Eric in the Land of the Insects is a fable about class divisions, keeping up appearances, the importance of diligence and the forces of money (in the book symbolized by honey and not by a soup tureen as it is in Jeanne Dielman). The book and the film both explore the contrast between pre-programmed behaviour and instinct or free will. The world of the insects, just as the one of Jeanne, starts to unravel because they begin to think about everything they’re doing and to mull over the existential question of whether they are acting by the bookChantal Akerman has said to her mother that Jeanne’s routines have to do with the latter’s past of being an Auschwitz survivor—they can be seen as a kind of internalized order of the repetitions of the camp where they meant the only way to stay alive for another day. Godfried Bomans began writing the book when World War II had already started and by the time of its release the Netherlands were occupied. In 1943, Bomans would hide Jewish people inside his house, for which he was posthumously honoured by the Israeli state. With already ten editions in 1941 alone, Eric was a hit as supposedly escapist literature during the war years. Yet, the war is present in the fairy tale. By the end, it clearly surfaces when the innocent Eric finds himself marching along with the bellicose ants—it’s their acid in his face that opens his eyes and throws him out of the painting, back to “reality”..

What’s striking is that just as much as Eric’s dream, the exterior world is also referred to in terms of painting. The book opens with a quote attributed to a letter by Leonardo da Vinci that is as fake as Jeanne’s postal code: “We all are exiles, living within the frame of some strange painting. He who knows this, lives greatly. All others are insects.” Further on, the author states: “didn’t we cry when we first found ourselves in the painting in which we have now so long been living?” And the last line reads: “Keep your eye on the frame.” Of course, Jeanne Dielman has also been described as someone who’s imprisoned in the film’s “painterly” compositions, to use that horribly hollow adjectiveAlthough often termed painterly or pictorial, one could just as well call Jeanne Dielman’s compositions “book-like”. Because the camera is often placed in a position along the vertical symmetrical axis of the given space, Ben Singer has linked the film’s individual frames to the reading of a book: the viewer begins to mentally fold the image down its spine. More persuasively, he also relates the film’s book structure to the temporal and structural symmetry that bisects the film exactly in the middle (ninety-five minutes) by the second customer’s visit. And in her Cahiers review, Daniele Dubroux observed how Jeanne herself is seen in the act of folding all kinds of things: clothes and (news)papers, but one could add the toile cirée, napkins, the convertible sofa bed, her reusable piece of aluminium foil, the breaded veal, and ultimately her own body in the bathtub or between the door opening in the hallway downstairs without touching it.. The critic Manny Farber characterized Jeanne as “locked within her three-room flat existence.” The book also revels in these kinds of representational or medium specific aspects. The portrait of Eric’s grandmother tells him: “We’re all flat. Just look,” and as she turns full circle, Eric sees that she’s barely as thick as cardboardAt the very end of Chantal Akerman par Chantal Akerman (1996), the director tells how her vocation as a filmmaker may come from her maternal grandmother who was a painter. When, one day, she asked her mother what those paintings were, she replied that she was little, but what she remembered was: “Women. Faces. Faces looking out at me. And that’s all.”. Belgian critic Dirk Lauwaert wrote how in Jeanne Dielman “each shot is hanging, like a piece of cloth nailed between two doorposts, or from the ceiling, or leaning on a tabletop.” Although it would go too far to see the book as a mise en abyme of the film, it can act as a key to examine in the rest of this text what pictorial universe Sylvian and his mother are exactly stuck in.

I.

In his visual essay on the Criterion DVD of Maurice Pialat’s L’Enfance nue (1968), critic and filmmaker Kent Jones claims that Pialat’s training as a painter doesn’t just show in his compositions or sense of light and colour, but in his stance towards his subjects: always one to one, attentive to people and their environments. Jones aligns this one-to-one painter’s stance, as he calls it, to two other filmmakers: Rainer Werner Fassbinder, exemplified in The Merchant of Four Seasons (1975), and… Chantal Akerman in Jeanne Dielman. In her reappraisal of the film, more than thirty years after her initial pan, Amy Taubin states: “The point of view is undisguisedly that of the filmmaker—just as the point of view of a painting is unmistakably that of the painter—regarding her subject, Jeanne.” In the same movement as comparing the film’s images to a canvas, Dirk Lauwaert also links them to “a retina, an eye without eyelashes or eye muscles.” Indeed, in Cahiers du Cinéma, Akerman stressed: “Ce qui m’intéresse justement, c’est le rapport avec le regard immédiat, avec le comment tu regardes ces petites actions qui se passent.” In another interview with Camera Obscura, she explained: “You know who is looking; you always know what the point of view is, all the time. It’s always the same. It’s always me. [A higher position] is not how I see the world.”

In what is still the best piece about Jeanne Dielman, ‘Kitchen without Kitsch’, painter’s pair Patricia Patterson & Manny Farber famously contextualized Akerman’s specific way of looking in a seventies tradition (albeit one that goes back to Ozu) which they termed shallow-boxed movies, as opposed to dispersal movies. They compare Jeanne Dielman, and especially its kitchen’s “still-shot-shallowness that seems estranged, cut off from neighbors or the rest of the city”, to Johannes Vermeer’s “equally bounded painting, [where] pettiness and grandness are blended in a seamless domesticity in which every item carries precise information and registers within a color that looks both slow and full.” Indeed, Jeanne Dielman is generally situated within the tradition of seventeenth-century Dutch genre painting. P. Adams Sitney and Steven Jacobs, among others, have noted how, similar to the film, many of the interior pieces by Vermeer, Pieter de Hooch, Gerard Terborch and Gabriël Metsu comprise lone figures, often self-absorbed, female characters in still poses, meditating near windows or open doors which suggest an exterior world that is not visible or only fragmentarily visible. If, for Farber & Patterson, Jeanne Dielman is the epitome of the shallow-boxed film, then Jacques Rivette’s Céline et Julie vont en bateau (1974) exemplifies the dispersed tradition. Again, they compare this film to another painter: “a Cézanne watercolor, where more than half of the event is elided to allow energy to move in and out of the vague landscape notions.” In The Language and Style of Film Criticism, Richard Combs discusses Farber & Patterson’s piece and leaves us with the rhetorical question if it isn’t a kind of soft-shoe to put that Céline et Julie is Cézanne, while Jeanne Dielman is Vermeer. So, what happens if we explore or tap into the wilder, Cézannian side of Jeanne Dielman?

To begin with, it has often been pointed out—by Peter Wollen (1981) and after him Ben Singer and Steven Jacobs, among others—that Jeanne Dielman occupies a singular split position between European modernist cinema (Jean-Marie Straub & Danièle Huillet, Jean-Luc Godard, …) and American avant-garde cinema (Michael Snow, Andy Warhol, …). However, one missing link between these two traditions might just be Paul Cézanne. Just a few, quick “anecdotes” here. These are all artists that, just like Cézanne, stressed the formal, perceptual and material construction of their representational work. Philosopher Gilles Deleuze was one of the first to point out that Cézanne has been for a long time Straub & Huillet’s mentor. They often presented their films in certain cities just to see one of his paintings and recognized that they had been thinking about Cézanne for over twenty years before they eventually made the first of two films about his work, Cézanne (1989) followed by Une visite au Louvre (2004), but not after initially passing the invitation by the Musée d’Orsay on to Jean-Luc Godard—who in Histoire(s) du Cinéma 1B dissolves his own face to one of Cézanne’s self-portraits. The reflection of Cézanne’s watercolours in Godard’s video work has been pointed out by Tom Paulus on photogénie and the spectre of the painter can still be seen up to his most recent multi-perspective 3D-experiments, but already by the time of Pierrot le fou (1965), Akerman’s cinema-awakening, the characters were compared to Cézanne’s apples. For his serigraphed Apples, Warhol turned to the ones of Cézanne and transformed them into pure form and colour. On multiple occasions, Michael Snow, who started out as a painter, expressed his admiration for Cézanne’s solution to balance illusion and reality, mind and matter. In a letter to P. Adams Sitney, Michael Snow used the same dichotomy when he described his work as “not very Cézannesque” and expressed his hope that “Wavelength and <—> are much more Vermeer.” However, he conceived La Région centrale—Akerman’s other big revelation—as “a gigantic landscape film equal in terms to the great landscape paintings of Cézanne,” and other French artists.

It’s nonetheless significant to note that in the same text, Farber & Patterson also call Jeanne Dielman “a still life film—a genre painting by a Seventies Chardin.” It was Cézanne who resurrected the Dutch still life as a form since the 17th century, via Jean-Siméon Chardin (and Édouard Manet). In his Letters on Cézanne, poet and novelist Rainer Maria Rilke wrote: “Chardin was the intermediary; his fruits are no longer thinking of a gala diner, they’re scattered about on kitchen tables and don’t care whether they are eaten beautifully or not. In Cézanne they cease to be edible altogether, that’s how thing-like and real they become, how simply indestructible in their stubborn thereness.” This brings to mind the remainder of the mentioned passage in the Cahiers interview where Akerman talks about her “regard immédiat.” She was asked by Louis Skorecki and co about words that are being used to describe her films, “hyperrealism” being one of them, and she continued about the kettle in her own kitchen still lifes: “Mais pour mon cinéma, j’ai plutôt l’impression que le mot qui lui convient le plus c’est phénoménologique. (…) Par exemple si je filme la bouilloire [the kettle] qui est là sur le feu, elle n’a aucun sens cette bouilloire, et l’image n’aura un sens que par la présence même de cette bouilloire, et donc elle rejoindra toutes les bouilloires, toutes les mémoires de bouilloires que tu as vus. Ce sera comme une évidence qui tout d’un coup s’impose.”

II.

It would be possible to look for explicit resemblances in terms of content, angle of depiction or the geometrical approach of Jeanne Dielman and Cézanne’s paintings, for example in La Femme à la cafetière [Woman with a Coffeepot] (1895) or Madame Cézanne dans un fauteuil rouge [Madame Cezanne in a Red Armchair, 1877]. Yet, is there one still life that better captures the whole of Jeanne Dielman in one image than Cézanne’s modest sized La Pendule noire (The Black Marble Clock, c. 1870)? In Interpreting Cézanne, sculptor and writer Sidney Geist notes how behind its realistic façade lurks an intense, muted drama with the brooding presence of the functionless clock, whose hour and minute hands went missing. Time is out of joint. Among the other disparate elements of this still life, there’s the monstrosity of the suggestive conch shell with its red lips and the dominating rock-like formation of the table cloth that might be a metaphor for the bed sheet—Farber described Jeanne’s linen as “a voluminous white mass which is like a tidal wave across the entire lower half of the screen.” It contrasts with the massive black marble clock. Reminiscent of the black and white chequered floor tiles that in Jeanne’s kitchen are surrounded by the yellows, greens and the whiteness of the Cubex cupboards, Rilke remarked how in this painting black and white behave perfectly equal and colour-like next to the other colours, as opposed to Manet’s black that, for him, has the (other Dielmanian) effect of a light being switched off.

As Akerman, Cézanne presents us with the quotidian exoticism of a bourgeois interior with an equal predilection for shiny surfaces (as gleamy as Jeanne’s dining table and woodwork) and different textures: the porcelain coffee cup, the transparency of the crystal or glass vase, the faience inkwell, the marble of the clock which together with the pink ceramic vase is doubled by the gold-framed mantelpiece mirror. In both cases, this material world, even though it treats objective matter, is deeply subjective at the same time. Just as Jeanne Dielman is a kind of portrait of Akerman’s mother, Cézanne’s still life is a portrait of his childhood friend, Emile Zola. It was painted in the writer’s house and hung in his dining room as a gift (before it was later owned by actor Edward G. Robinson). “Equality of all things. Cézanne painting with the same eye and the same soul a fruit dish, his son, the Montagne Sainte-Victoire,” wrote Robert Bresson in his Notes on the Cinematographer (1975). Indeed, Cézanne shared with Chardin a rejection of the hierarchy of genre. The objects on his table are of no less significance than the figures in some painted ‘story’. In a similar vein, Akerman stated that the fact that “the milk might spill, is as dramatic as the murder.”

Just as the fixity of Jeanne Dielman’s low camera position draws attention to the boundaries of the image—think of the truncation of Jeanne’s head while receiving the first two visitors, to name just one example—La Pendule noire’s perspective is below eye level and framed in a photographic manner in which the top cuts off a vase in the middle. Moreover, this painting of course also confronts us with Cézanne’s departure from traditional single point perspective. Here, he tinkered with front and side view. In his Card Players (1890-1895)—an obsessive project in which he made five versions of a set-up similar to the side view on Jeanne’s kitchen, perpendicular to the windows—we see the table from the front as well as from the top. Many of his other still lifes are tilted down, angling towards us, like a knife or spoon could fall at any moment.

While in Vermeer time seems to stand still, Cézanne’s pictorial organization inserted the dimension of temporality into a static space. Film and art scholar Angela Dalle Vacche notes that “Cézanne’s concern with time and change at the level of appearances challenged the idea of a timeless, stable, and exclusively mental vision.” Seeing the objects from multiple angles and suggesting a synthesis of successive moments in time, the observer thinks successively as well as simultaneously in his imagination. In a way, Cézanne allows traces of memory or gives rise to the possibility of structural variation. The Belgian art historian Thierry de Duve has shown how Jeanne Dielman “articule trois images, trois concepts, trois formes du temps l’une sur l’autre.” In a discussion with de Duve, Olivier-René Veillon, who would later write the study Seul comme Cézanne (1995), remarks: “Si on compare les trois journées – l’analogie de cadrages – la superposition des images conduiraient à trois séries d’images qui en révèlent une… Il y a donc une image unifiée.” Various video-essays have visualized this idea of a kind of mental multi-temporality present in the film’s recurrent set-ups. In Regarding the Pain of Jeanne Dielman (2016, 3’), David Verdeure demonstrated this with a simultaneous collage of the shots where the camera is set up perpendicular to the long wall of the kitchen. In the first chapter of Les variations Dielman (2010, 11’), ‘Le spectre de la routine’, Spanish editor Fernando Franco did this for the two shoe shining scenes. In Day x Day x Day (2014, 1h46), professor Drew Morton layered the film’s three days upon one another in one non-linear viewing.

Nevertheless, one of the main reasons why Jeanne Dielman is generally associated with Vermeer and 17th century interior painting is its accentuation of quattrocento perspective. Steven Jacobs outlined how Dutch seventeenth-century genre painting domesticated, so to speak, the geometric linear perspective of Italian Renaissance painting. Ben Singer noted that thanks to Akerman’s low camera position and the fact that the vanishing point lies in the exact geometric centre of the screen, the objects in the field indicate the lines of sight more clearly than in other films. He speaks of an amplification of illusionism in Jeanne Dielman. Ivone Margulies shares this observation as, for her, the film “is characterized by a hypostasis of illusionist perspective and realist representation,” which are no opposites. Yet, others, such as the critic Ruby Rich, make a case for Jeanne Dielman as an anti-illusionist film. She states that “invoking realism, even with a hyphenated modifier [such as Margulies’ hyper-realism], for this film is rather like extolling the murderer to the victim.” The French novelist and scholar, Benoît Peeters, even calls Jeanne Dielman “pas seulement un film non-réaliste, c’est, plus encore, un film véritablement anti-réaliste, une formidable machine de guerre anti-naturaliste.”

III.

In essence, the film indeed seems closer to Cézanne’s anti-illusionism, than to the illusionist and more objective mission of Vermeer, for which he might have used the camera obscura. Cézanne’s apples coming out of the tube of paint are nothing but colours. What else are Akerman’s bottle of Dreft and the dishwashing brush but a needed blob of green, or the dish rack but another touch of yellow? Let’s return one more time to that other kitchen in L’Enfance nue. In Film Comment, filmmaker Jean-Pierre Gorin wrote: “stay in this kitchen for a while, (…) the whole room is filled with patches of yellow and blue, falling somewhere between Courbet and Cézanne.” Why can this latter kitchen be Cézannian, while the one of Jeanne Dielman would be Vermeerian? So, a more constructive perspective than Mary Jo Lakeland’s highly symbolic reading of Jeanne Dielman’s colours, or Ivonne Margulies’ vague claim that “the palette recalls Flemish painting”—whatever that may mean—could be to look at Cézanne’s use of what he called modulated colour. He moved away from a representational “modelling” with dark and light, such as Vermeer, to “modulating” with colour in his approach to composition. Other than Vermeer’s famous light from the left, Cézanne used a much more general, diffused kind of light. To a similar effect, Jeanne Dielman’s cinematographer, Babette Mangolte, had to use soft photoflood lighting attached to the ceiling because of the restrictions of the narrow apartment. As in the painter’s case, space seems much more determined by building colour relations than the incidence or effects of light. With his colour blocking and working side by side in planes, Cézanne gives three-dimensionality while maintaining an element of two-dimensionality.

In his landscape paintings, too, Cézanne creates deep space while at the same time resisting it. By way of his use of colour, roads blend in with foliage, a house or the sky. Similarly, Jeanne and her son blend in with the apartment spaces—her mahogany hair against the woodwork, the green of her coat and the hallway wallpaper, her flesh tone matching the pinkish bathroom walls, the squares of her smock and the one on the tiles, curtains and towel in the kitchen, …The Fondation Chantal Akerman notes that in the grading process of the restoration Akerman emphasized that the colours of the interiors were subordinate to the colour of the hair and skin of Delphine Seyrig; most important was that those colours were the same each time. One last time Gorin on the Cézannian L’Enfance nue: “It’s patterns all around. On the old woman’s kitchen frock, on the tablecloth, on the curtains. And it’s the same baroque accumulation in every room we’ll visit.” For him, “the minimal simplicity” of this home coexists with “the visual complexity of the patterns that fill and mold (…) an amazingly, almost maddeningly, texturally busy space.” Affirming the flatness of the canvas, Cézanne often left no optical escape. Like the boy in the book he’s reading, Sylvain, together with his mother, seems stuck in this pictorial space. The characters of the novel and film share a perceptive sense of reality or “the frame”, a modern experience for which Cézanne helped to lay the foundation. What struck Dirk Lauwaert in Jeanne Dielman was “an air of study about this film, [that] welcomes intense reflective attention.” For art critic Jonathan Crary, Cézanne’s work as well is characterized by a sustained attention, even a “relentless attentiveness to attention itself”, that’s simultaneously a piercing social estrangement and inseparable from the onset of the dissolution and disorganization of the world.

In Les Rideaux (Curtains, 1885), Cézanne painted a curtained doorway suggesting the threshold of a world beyond the studio, out of the painting. The curtains point to the theatricality and affirm the drama. Next to her front door, Jeanne Dielman has a storage closet (?) covered by a patterned curtain that ominously waves every time someone passed by—it’s the only space in the apartment that we never see opened. It’s either framed together with the entrance or exit of her flat, or with the corridor leading up to the bedroom door that, for the first two days, prevents us to see what happens there, offscreen, until the outside world is about to kick in at the end. “Keep your eye on the frame.”

Thanks to Gerard-Jan Claes, Steven Jacobs and Bart Versteirt for their suggestions and remarks.

Works Cited

Godfried Bomans, Erik of het klein insectenboek (Utrecht: Het Spectrum, 1941). Translated into English by Regina Kornblith in 1994 (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt) and into French by Marianne Ranson and Tilly de Hes in 2006 (Alice jeunesse).

Richard Combs, ‘Four Against the House’, In: Alex Clayton and Andrew Klevan (eds.), The Language and Style of Film Criticism (New York: Routledge, 2011), 121-138.

Jonathan Crary, Suspensions of Perception (Cambridge: MIT Press, 1999).

Christina Creveling, ‘Women Working: Chantal Akerman’, Camera Obscura 1 (1976), 136-139.

Gilles Deleuze quoted in Sally Shafto, ‘Artistic Encounters: Jean-Marie Straub, Danièle Huillet and Paul Cézanne’, Senses of Cinema 52 (2009).

Danièle Dubroux, ‘Le familier inquiétant (Jeanne Dielman)’, Cahiers du cinéma 265 (1976), 17-20.

Thierry de Duve, ‘Les trois horloges’, In Jacqueline Aubenas (ed.), Chantal Akerman: Actes du Colloque 14-15 février 1981 (Brussels: Ateliers des Arts, 1982), 87-96.

Many Farber and Patricia Patterson, ‘Kitchen Without Kitsch’, Film Comment 6 (1977), 47-50.

Steven Jacobs, ‘Semiotics of the Living Room: Domestic Interiors in Chantal Akerman’s Cinema’, In: Anders Kreuger and Dieter Roelstraete (eds.), Chantal Akerman: Too far, too Close (Antwerpen: Ludion, 2012), 73-87.

Mary Jo Lakeland, ‘The Color of Jeanne Dielman’, Camera Obscura 3-4 (1979), 216-218.

Dirk Lauwaert, ’23, quai du Commerce, Brussels. On Chantal Akerman [1975]’, Sabzian, 13 February 2019; translated by Sis Matthé.

Ivone Margulies, Nothing Happens: Chantal Akerman’s Hyperrealist Everyday (Durham: Duke University Press, 1996).

Annette Michelson, ‘About Snow’, October 8 (1979), 111-125.

Benoît Peeters, ‘Jeanne Dielman: le manque et le supplement’, In Jacqueline Aubenas (ed.), Chantal Akerman: Actes du Colloque 14-15 février 1981 (Brussels: Ateliers des Arts, 1982), 79-84.

Louis Skorecki, Danièle Dubroux & Thérèse Giraud, ‘Entretien avec Chantal Akerman’, Cahiers du cinéma 278 (1977), 34-42.

Ben Singer, ‘Jeanne Dielman: Cinematic interrogation and ‘amplification’’, Millennium Film Journal 22 (1990), 56-75.

Michael Snow & Louise Dompierre, The Collected Writings of Michael Snow (Waterloo: Wilfrid Laurier University Press, 1994).

Amy Taubin, ‘A Woman’s Medium’, Artforum, January 23, 2009.

Olivier-René Veillon, ‘Le fiction contre le récit’, In Jacqueline Aubenas (ed.), Chantal Akerman: Actes du Colloque 14-15 février 1981 (Brussels: Ateliers des Arts, 1982), 100-106.

Peter Wollen, ‘The Two Avant-Gardes’, Studio International 978 (1975), 171–175.