It seems like an eternity has passed ever since I read the biography of Freud wherein, towards the end of his life, he is reported to have said: “My world is a small island of pain floating on an ocean of indifference.” When one of the themes of the, now cancelled, Summer Film College organized by the same institution bringing you this volume, was announced as being ‘teenage angst’, I proposed this quote as a guiding principle for a collection of texts that would have the ambition to serve as a companion piece. A few weeks later the world went into lockdown.

It was impossible to foresee how much we all would become quarantined islands floating in a sea, not of indifference—unless we would take into account that nature does not particularly care as much about humankind as we would like to believe—but of moralizing interpretations of a virus that set the way we live now on edge. Even more recently, a real archipelago of pain rose to the surface of a real ocean of indifference, that of institutional racism, making tidal waves that hopefully will not subside without reaching and changing all our shores.

The following texts are not about these issues. Conversations have been had about the necessity to address them but in the end, we decided not to make changes to the texts that had by then been in the last stages of development. Even though we unequivocally support the protests and riots and especially the motives and feelings (of pain and anger) behind them, it seemed better, for us, to not try to “catch this wave” too easily. We do not want to be a brand publishing a black square on their social media for cheap economic and social gains. This is the moment where we will start thinking about how to address these issues in a meaningful and necessary way.

What these texts are about is a particular kind of existential experience; growing up in a world you were thrown into without a choice. ‘Growing Pains’ could have been another title, since these texts explicitly deal with the transformation of a child into something that could be described as an autonomous self. There seems to have been a particular predilection for the French cultural idea of this particular topic, for which I blame Rimbaud, since more than half of these texts deal with the cinematic output of the country of ‘Mai 68’, arguably the most well-known outburst of youthful dismay.

Although the first piece in this collection does not directly involve itself with French cinema, Tijana Perović asks herself the quintessential existentialist question, “If I was not born, but made into a woman, how has this influenced my growing up?” Closely examining American documentary maker Lynne Sachs’ The House of Science: A Museum of False Facts (1991), in which she dissects the way women have learnt to see their bodies through the clinical, male gaze. For Perović, the cuts Sachs makes open up the discourse on female fluidity and its liquid embodiment.

Maximilien Luc Proctor, or MLP, interpreted the theme of growing pains in a formalist way. He looks at three short to medium length films by accomplished directors that also focus on the world of adolescents with all their trials and tribulations. Juxtaposing the films of Straub-Huillet, Markopoulos and Brakhage while grounding each of them firmly in the respective careers they were a part of, what he succeeds in doing is reinstating a sort of appreciation for these much too easily overlooked shorter works, which seems something particular to cinema. Nobody ever denounced Beethoven’s sonnets solely because he also wrote symphonies.

The world of fairy tales is unsurprisingly the starting point for the most perverse and subversive piece of the collection. Close-reading Bluebeard by grande dame of French provocation Catherine Breillat, Ruairí McCann delves into the fantasies and oneiric landscapes of female sexual awakening. By meticulously looking at how male and female bodies are (re)presented on the screen, he tries to make sense of the ambiguous power relations we have come to expect when dealing with revisionist interpretations of older material. Luckily for him, and us readers, he finds some pleasure in this perversity too.

A lot has been said about the Golden Age of Television but the mid-90s Arte-project Tous les garçons et les filles de leur âge puts everything that came afterward to shame, as evidenced by the exhaustive two-part text Tobias Burms and Joseph Pomp have dedicated to it. Diving deep into these nine films by household names as Akerman, Denis, Assayas and Téchiné, next to lesser known or even already ‘forgotten’ directors, they paint a portrait of youth spanning a good part of the second half of the 20th century. Possibly the most political piece, in subject and style, they nevertheless make sure each chapter includes the indispensable party.

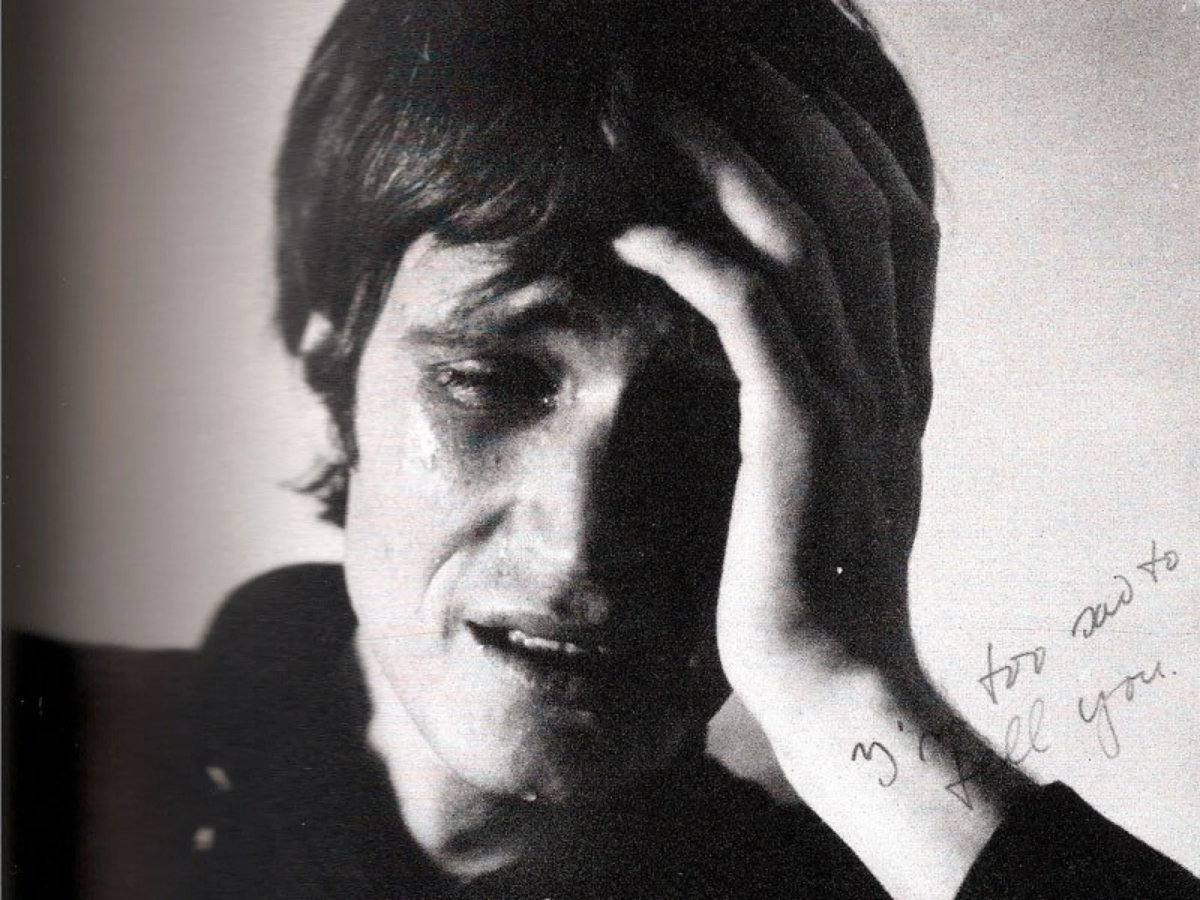

My own piece concluding this collection is the most directly influenced by the current virological crisis. When thinking about youth and youth wasted I kept seeing these images of a young woman rolling down the bank of a river, an island drowning itself in the ocean. I have tried to come to terms with this young woman and another young man, both having been born from the brain of Robert Bresson. By juxtaposing their lives and deaths and zooming in on the many similarities between their respective stories, I tried to reckon with the question whether suicide can have meaning in a world devoid of just that. It was not my intention to convince anybody but myself. These stories of pain and indifference luckily remain inconclusive, leaving open the ambiguity we need to stay alive.

Now the world has opened up again we send these stories of pain into it. In hopes of not finding it as indifferent as it was before.