In several interviews, filmmaker and novelist Catherine Breillat has stated that her origins as an artist stemmed from an isolated adolescence, imposed by her parents who in response to the early onset of her puberty, at the age of 11, began keeping her indoors and away from others as much as possible. In hindsight, Breillat understood this decision as a recidivist act, semi-consciously made. She was beginning to change into a sexual being which meant her parents would gradually cede their influence over her to others and to her own independence. So, they tried to delay the inevitable by hiding her away.

The unintended upshot of this physical confinement was that it gave her the time and space to develop intellectually. Allowing her to read extensively and precociously, with the works of Marquis de Sade and Georges Bataille eventually making the deepest imprints. Both were philosophers and provocateurs that found prose fiction especially fertile ground for critiquing the dominant religious and political systems of their day. Their outré depictions of sex were, in part and particular, feints against the hypocrisies of conservative morality that also laid bare on the page, diagrams of hierarchy.

Their ideas made such a profound impact on a young Breillat that they not only provided a conduit for her burgeoning self-comprehension but for her future artistic endeavours. Laying down the scope and shape of her art which, from her first novel L’Homme facile (1968), written when she was 17, to her latest film Abus de faiblesse (Abuse of Weakness, 2013), has been a life of political and philosophical inquiry through fiction. Focused on how not only sex but a woman’s conception of her own sexuality are used as casus belli and the tool for her subjugation.

Breillat’s own tools include a wide range of stylistic and genre conventions. Her ability to deftly derive confluence and subversion with such a clear understanding of their original context and implications, marks her out as a formalist nonpareil. The fairy tale is one of her most distinctive appropriations, arrived at with a duology funded by the French television station ARTE: Barbe bleue (Bluebeard, 2009), and La Belle endormi (Sleeping Beauty, 2010). Out of the two, Bluebeard is particularly potent, in how it uses Breillat’s analytical and stylistically polyamorous approach to blend this ancient and enduring mode with her other influences and depict the transition between childhood and adolescence.

The fairy tale, like myths, fables and other forms of folktale, is an international phenomenon that was initially passed down, for centuries, as a predominantly oral tradition with no fixed authorship or composition. One of the first major attempts to summate the genre—in a Western European and specifically French context—was undertaken by Charles Perrault (1628-1703), a writer of Parisian, bourgeois birth and of many pursuits. And yet his legacy has not been built on his art advocacy or a bibliothèque bleue containing a barbed critique of traditional theatre aesthetics. Instead he is largely remembered for a post-retirement project, Histoires ou contes du temps passé (1697), a book of fairy tales that he collected, refashioned and then published under his son’s name.

Not only a work of ethnography, Perrault significantly modernized these age-old class-transcending tales, expanding them with ornate descriptions and a wry literary voice in order to suit the tastes of his prospective audience, the aristocrats who frequented the capital’s salon culture. Though alterations were made not just for the sake of cosmopolitanism but also to keep readers’ interpretations in line with propriety, for each story ends with a ‘moral’ of Perrault’s creation, devised in compliance with an overarching catholic and paternalistic moral vision.

Yet the actual experience of reaching and reading one of these morals is often capped with confusion rather than newfound moral clarity, for its pedagogical function is undermined by their status as addendums, with judgments often at odds with the course of the preceding story. This disjunction sits at the heart of the fairy tale’s secret complexity. After Perrault, it was and is a commonly held position that fairy tales are for children, to entertain but also to ensure their moral development, with the clear-cut and simplified characterization and narratives supposedly conductive to teaching right and wrong. Yet, while it is true that these stories are explicitly concerned with exalting normative behaviour—with disproportionate attention paid to regulating feminine conduct—and with discrediting divergence, their hundred-father parentage, archetypal ingredients and the centuries’ worth of shifting societal taboos and expectations through which they have been filtered, grants them an ambiguity.

This open-endedness was for Breillat a point of attraction, and in her view is what makes them ideal for children, in the sense that it encourages their inner life rather than stifles it:

Breillat’s account of her relationship with her favourite fairy tale, Bluebeard, is a strong case study. It is the story of a lord with a devil’s beard and a suspicious habit of marrying wives who soon after disappear. His newest bride gets to the bottom of this mystery by breaking a cardinal rule and entering a forbidden room, which she finds decorated with the bodies of his victims. Now that she has discovered the truth, he feels compelled to kill her. Though she manages to convince him to grant her a stay of execution long enough for her to muster her brothers, who in the nick of time swoop in and slay Bluebeard.

Perrault’s moral offers a hairpin turn, encapsulating a tale run riot with a murderous incarnation of masculine dominance with assurance that such men have been relegated to myth and history and a condemnation of feminine curiosity. And yet a five-year-old Breillat wasn’t scared into passivity. The story instead excited her and she would return to it again and again, throughout her childhood, all the while developing an increasingly complex interpretation that turned Bluebeard from a one-dimensional monster to a human being tragically imprisoned by his monstrous flaws. While the relationship between him and his wife remained that of a master and slave, wolf and lamb, it is also complicated by insinuations of genuine mutual affection.

Her approach to adapting Bluebeard reflects this intertwining of deep appreciation and critical distance, for it isn’t straightforwardly revisionist. She doesn’t modernize the setting or drastically alter the plot. Rather the story is amended and challenged by the overt presence of multiple interpretations, running parallel and muddied across and two plotlines. One is a direct dramatization of the tale itself, taking up the bulk of the film’s 78 minutes, and the other is a frame narrative set in modern times which routinely interrupts the former.

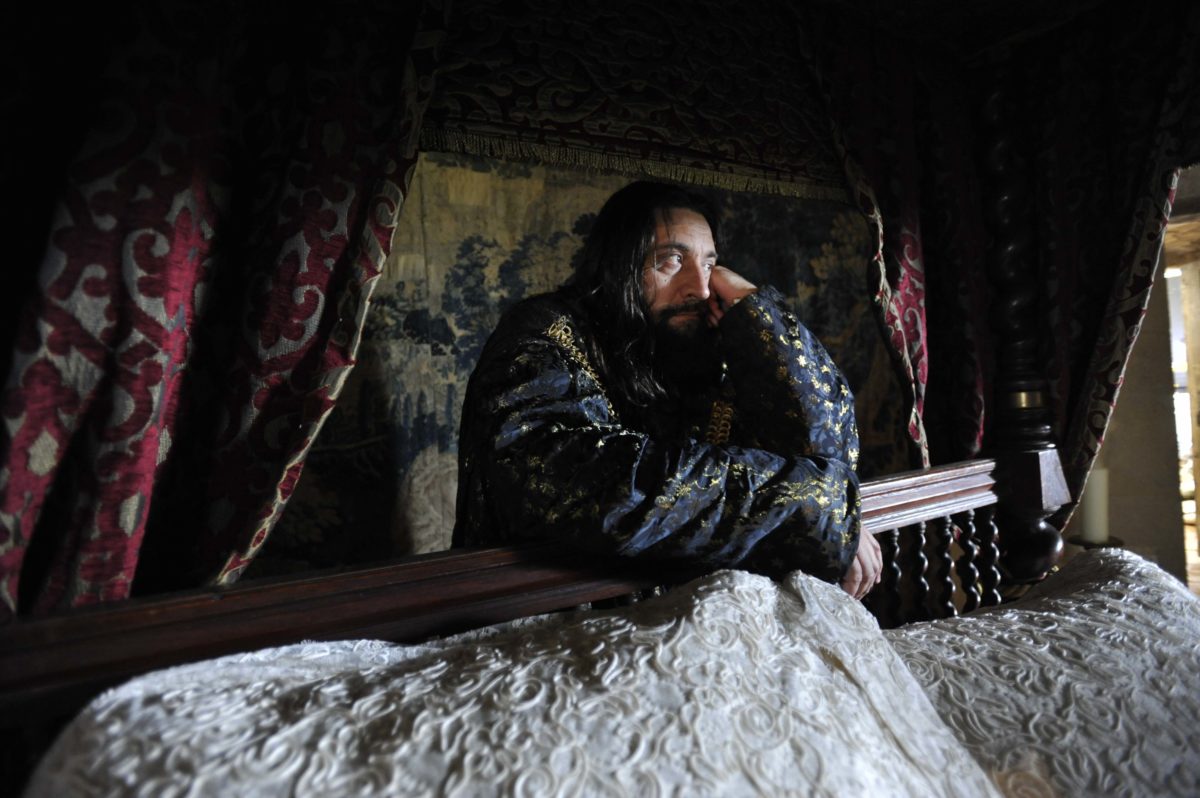

Breillat tells the story mostly from the perspective of two pairs of sisters. The first introduced are the bride-to-be, here called Marie-Catherine (Lola Créton), and her sister Anne (Daphné Baiwir). Simply the daughters of a ‘lady of quality’ in Perrault’s version, Breillat’s adaptation devises a new background taken whole cloth from the opening of de Sade’s Justine—a novel that itself is fit to burst with bluebeards. They are introduced as the teenaged wards of a convent, from which they are expelled as soon as news arrives that not only has their father died but also has left them penniless. While on a buggy back to their mother and an impoverished existence, they pass Bluebeard’s (Dominique Thomas) castle, whose crimes, in this rendition, are not just vague rumours but common knowledge.

Their reaction to this sight of both the stage and prize of tyranny delineates their personalities and views of the world. Anne is the older and seemingly more dominant sibling. Her grief is closer to rage and it is funnelled into a pessimistic diagnosis of the world. To her Bluebeard is not a one-off but the epitome of how the disadvantaged are unjustly sacrificed at the altar of the wealthy, ergo, powerful. Marie-Catherine echoes her sister’s disgust but also is openly in awe of Bluebeard’s spread. It would seem her view of the world is more muddled, but her wish that one day she will be just as rich, so she can return to the convent and strangle the abbess, is first sign that she has a clear view of the workings of a world; with the ambition to work within its bounds, as opposed to Anne, the Justine to her Juliette, who leans more towards opting out.

In the frame narrative, we are introduced to the second pair of sisters. Catherine (Marilou Lopes-Benites) and Marie-Anne (Lola Giovannetti) are much younger than their fairy tale counterparts and enter the film not in state of poverty and grief but of play and speculation. They have stolen themselves away up into a loft where, with a copy of Perrault’s collection at hand, they read through and comment on Bluebeard. This is an explicitly autobiographical element, inspired not only by Breillat’s initial attachment to the story but specifically by how it recreates the memory of her, as a child with a rebellious streak, reading the story to her more mild-mannered older sister Marie-Hélène with the intention of scaring her. This dynamic is transposed on-screen, with their balcony box style heckling and observations, and the digressions that develop reveal that the younger but more dominant sibling Catherine relishes the tale’s grotesque elements. Marie-Anne on the other hand is disturbed by the violence and instead gravitates to the more romantic elements and the promised return to a social equilibrium.

Breillat delineates these two sets of sisters and the worlds and perspectives they inhabit with a complex form. She portrays the world containing the actual tale as an overtly fictional space through an amalgamation of realist and more manifestly stylized choices. Its representation of provincial 17th century France as a sparsely populated land of bare stone constructions and undergrowth could be seen as historically accurate and yet it has a streamlined quality—the convent, the sisters’ home and Bluebeard’s castle seem to be the only landmarks—that suggests not realism but the topography of both fairy tales and a philosophical novel like Justine, in which the world is pared down to the most extreme demonstrations of power and its inequities. The performances too are stylized with every line delivered measurably and crystal clear with the actors rigidly blocked, often in medium shots with minimal sets, as if on a proscenium or in portraiture. This jars with the little girls’ freewheeling patter, which was considerably improvised. Yet their confinement to a single, discrete location and to each other’s company also gives their scenes a closed-in analytical quality.

Breillat’s purpose in constructing this very particular form and the weaving together the two strands, is to incite an audience to engage with the characters and their dilemmas emotionally, but also to think consciously about how the story operates as fiction and reflects the differences in experience, from one stage of life to another. Catherine and Marie-Anne are pre-pubescent, with their loft a microcosm of those initial few years and forays into consciousness, what Simone de Beauvoir called the first “radiance(s) of subjectivity,” where, though not completely free of authority or expectations, a child’s sense of self, including gender and sexuality, is in a state of flux, with values and attributes being chopped and changed and often more uniquely interpreted. Conversely, adolescence—which Marie-Catherine and Anne are in a particularly brutal enactment of—is the often-painful process of stabilization, brought to bear by the fact that the identity can no longer exist in and of itself, semi-discrete, but instead is moulded directly by an increased role in a larger, stricter social order.

The film’s side-by-side structure allows direct comparison between how each set of sisters react to or reflect on the same events, the loss of a father being a significant early example. Catherine and Marie-Anne are seen trying to process the idea but it sits too far outside their purview for them to grasp it either as an immediate, visceral experience or the wider implications it would have on a family’s financial and social standing. Ultimately, they can only view it in a fantastical light. A playful pipe dream where one of the very few concrete authority figures in their lives has been removed with nobody or nothing in kind to take his place. This contrasts sharply with the event’s depiction in the tale. Where there is not only the debilitating and unrelenting pain of losing a loved one but an additional gut punch in realizing that their father’s sovereignty is not now there for the taking but still resides with him. Even in death. That is, in a society where authority is synonymous with a patriarchal figure, they have been reduced to a purgatorial state of destitution and disreputability until a replacement can be found.

An even more complex interaction is how the little girls’ conception of marriage compares to the trajectory of Marie-Catherine and Bluebeard’s relationship. Marie-Anne’s view is the illusion, matrimony as the consecration and celebration of the love between a man and a woman, with nothing transactional, exclusionary or obligatory about it. Catherine responds not with her own rival conception but with a surreal and subversive jab, declaring that another name for a man and a woman in love is homosexual.

The actual relationship, as depicted, is neither convention wholeheartedly accepted nor mocked and rejected. Instead, it takes the shape of one of Breillat’s favourite character set-ups and psycho-dramatic petri-dishes: a claustrophobic masculine-feminine tête-à-tête. A push and pull of foisted and self-definition. Their relationship is still an uneven playing field but one which Marie-Catherine has accepted, in part to butt up against and even redefine its boundaries, bit by bit, from the inside. This is hinted at from their very first meeting, when Marie-Catherine wanders away from a party—organized by Bluebeard at his castle as part of their matchmaking ritual—to find him drunk, alone and slumped against a tree. Since he is in a prone position it is she who towers over him, which Breillat emphasizes by cutting between her, at a low angle and in close-up, engulfing the frame, and him, seen from a high angle and in a medium shot, relatively pint-sized.

Once wed, Marie-Catherine continues to assert herself, refuting the role of a kept and cloistered wife. She not only refuses Bluebeard sex but takes the next, pointed step by having servants remove her bed from his chambers and place it in a room of her own, an empowering reversal of an earlier scene, where debtors came to claim her family’s furniture. Bluebeard not only acquiesces to these demands but in response to her taking on the more authoritative position, drifts into a role close to that of the passive spouse. Such is the case in a scene where Marie-Catherine watches him undress, his bare, barrel chest becoming an object, not the subject, of desire. This is all accentuated by Breillat’s direction, which often stages the couple side-by-side, where Bluebeard’s huge frame, amplified by furs and cloaks, dwarfs Marie-Catherine. And yet Créton’s steely composure not only counters but also dominates Thomas’ soft and doting demeanour.

This subversive dynamic is encapsulated with a final direct to camera image. Breillat’s moral, if you will, not only reinforces the fairy tale as a malleable form, but overrides Perrault’s own summarization—with its call for capitulation—by replacing it with a very definite dream-image of masculine authority bloodily overthrown at the hands of his patrimony.