Throughout his numerous films from 1980 through the present, the Palestinian director Michel Khleifi has developed a celebrated cinematic aesthetic that blends documentary footage with fictional narratives to construct lyrical portrayals of Palestinian life under military occupation. Khleifi’s films distinctively suffuse realism with elements of fantasy and myth to reimagine the multilayered memories and many-sided visions of Palestine that defy official histories imposed from above.

Born in Nazareth in 1950, Michel Khleifi worked as a car mechanic before leaving Palestine in 1970 with the intention of working for Volkswagen in Germany. Along the way, Khleifi visited a cousin in Belgium, where he ultimately stayed and has lived since. Khleifi studied at the Institut National Supérieur des Arts du Spectacle (INSAS) in Brussels and worked for Belgian television before making his first films. CINEMATEK, the Royal Belgian Film Archive, has recently restored several of his works, including Ma’loul Celebrates Its Destruction [Ma’loul fête sa destruction] (1985), Wedding in Galilee [Urs al-Jalil] (1987), Canticle of the Stones [Nashid al-Hajjar] (1990), and Tale of the Three Lost Jewels [Hikayatul jawahiri thalath] (1994). This restoration bears the possibility of establishing new critical discourse on Khleifi’s oeuvre and his legacy as a foundational figure of Palestinian cinema. Indeed, the formal innovations that Khleifi inaugurated between documentary and fiction as well as his labyrinthine approaches to Palestinian historical memory continue to resonate and be pushed in imaginative directions by contemporary Palestinian diasporic filmmakers like Larissa Sansour and Basma Alsharif.

The importance of Khleifi’s achievements comes into focus when set against the historical contexts and practical challenges of filmmaking in Palestine. Until the late 1970s, the primary depictions of Palestine by Palestinian directors were limited to films produced under the directives of the Palestinian Liberation Organization. Though the reception of these films did not extend far beyond Palestine, their idyllic depictions of life before 1948 were influential in galvanizing resistance to Israel’s erasure of Palestinian claims of territory and identity. Yet their nostalgia for a lost homeland overwhelmed a stance of critical distance towards Palestinian society. Meanwhile, Palestinians and Arabs were largely stereotyped through negative portrayals in both Western and Israeli cinema.

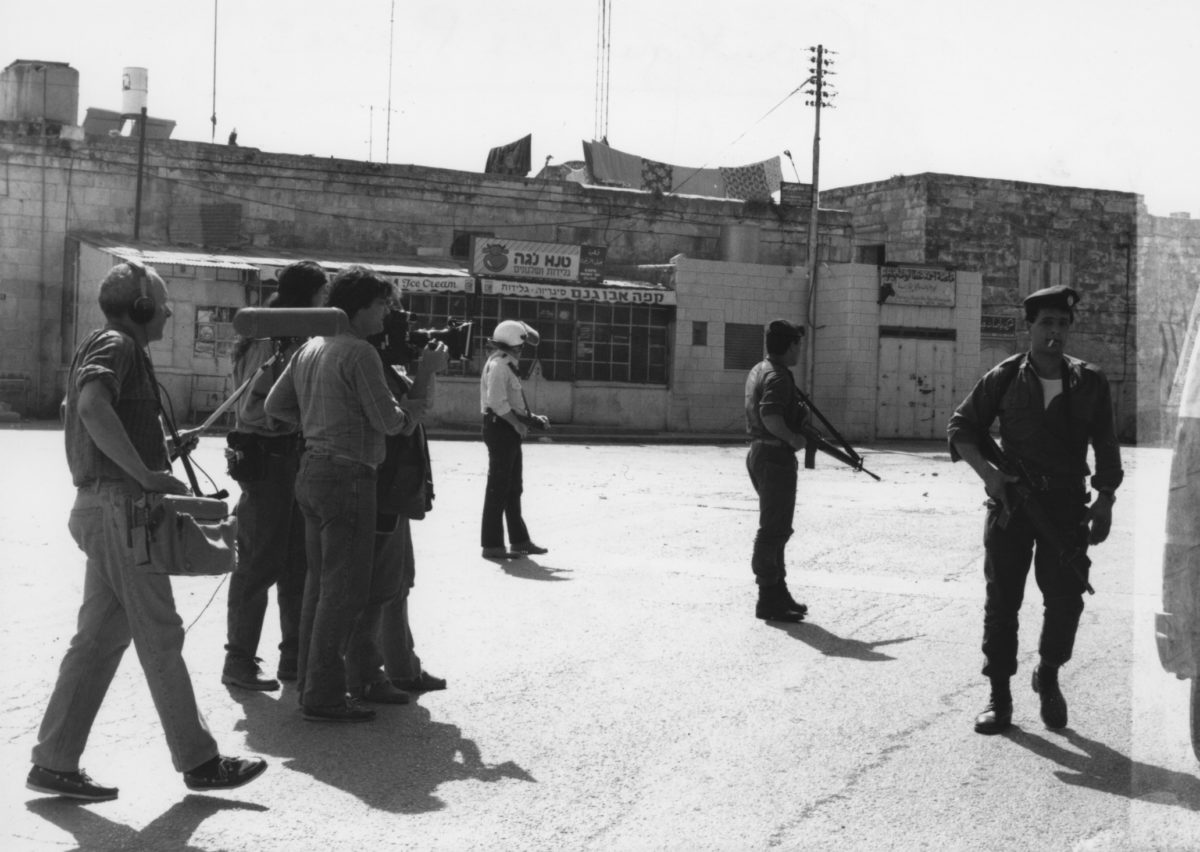

Khleifi’s films faced numerous complications at the time of their production: difficulties obtaining funding for making films in and about Palestine; a lack of resources and training in cinema in Palestine; few distribution channels in Palestine and the Arab World; ubiquitous anti-Palestinian media that hindered distribution in the West; Khleifi’s own alienation due to migration; and the profound struggles of filming within shifting circumstances of the occupation’s curfews, surveillance, interference, and ongoing violence. Yet Khleifi also worked from within an absence of filmic representations of Palestinian society authored by Palestinians themselves. Not only do Khleifi’s films challenge the Israeli military occupation across multiple periods of Palestinian history while refuting Orientalizing stereotypes. His dreamlike narratives, more significantly, attend to and critique the complexity and internal contradictions of Palestinian society—precariously suspended between tradition and modernity, among hierarchical relations between men and women, and across generational divides between those who experienced Palestine before the occupation and the youth who know no outside to its reality of conflict.

Ma’loul opens with sped up documentary footage of the end of the British Mandate, and the film is intercut with archival sequences of the village’s former landscape and community before its devastation. The tactile graininess of these archival inserts conjures historical loss and the porosity of memory while simultaneously visualizing what Edward Said saw in the films of Khleifi: “a utopian image making a possible connection between Palestinian individuals and Palestinian land.”Edward Said on Michel Khleifi quoted in Brenna Bhandar, Colonial Lives of Property: Law, Land, and Racial Regimes of Ownership (Durham: Duke University Press, 2018), 112. Between these archival fragments, the film portrays the return of Ma’loul’s exiled Palestinians to their native village and former property—an action only allowed once annually on Independence Day. This juxtaposition between the reality of past destruction and the survival of rights to a remembered land is underscored in further scenes, such as in one where an interviewed man returns to the ruined foundation of his former house. While Khleifi positions the village as a witness of Palestine’s destruction, the interviewee suggests the potential of reversing the erasure of rights, declaring that “rights don’t disappear as long as you lay claim to them.” By exposing the endurance of this place in spite of 1948’s aftermath in Ma’loul, Khleifi initiates a central idea explored throughout his films, that the rights of Palestinians “are dormant in the trees, valleys, dishes, fields, seeds, objects, structures, ruins, norms, and traditions that still subsist.”Ariella Aïsha Azoulay, Potential History: Unlearning Imperialism (London and NY: Verso, 2019), 478.

Unlike that older generation, I had to get inside of the defeat…of course, we blamed it all on Imperialism or Zionism or whatever, but what I realized was that there’s another element besides the balance of power, and that other element is in us: the strength of Israel comes from our weakness, but our weakness doesn’t come from their strength; it comes from the layers of contradictions and archaisms within our society…so I tried to put together a film that talks about it, that goes inside the power relationship to know why it’s like that.Miriam Rosen and Michel Khleifi, ‘Wedding in Galilee: An Interview with Michel Khleifi’, Cinéaste (Vol. 16, No. 4, 1988), 52.

Throughout the film, Khleifi stages these internal contradictions in gendered terms. Not only do the men of the village denounce the Israeli presence at the wedding as an emasculation of Palestinian tradition. But numerous scenes of male impotence, autonomous women, and domestic violence also position Palestinian women—and by extension Palestine itself—as at once the sacrificial objects of patriarchal customs and as liberated agents of future self-determination.

Wedding in Galilee destabilizes a singular account of the wedding through the intercutting of contrasting perspectives, a technique Khleifi extends in later films like Canticle of the Stones to fragment subjective viewpoints and the temporalities of historical time. The cinematography and dramaturgy foreground internal clashes of gendered experiences while contesting the visual logics of occupation. When the Israeli soldiers attend the wedding, they are placed at the periphery of the ceremony and appear at the edges of frames, a reversal of inside and outside that Khleifi choreographs to evoke—still thinkable at its time—future possibilities of co-existence. The film thus provides a vivid account of how collective joy continues to survive under the fraught circumstances of military occupation and the waning of patriarchal traditions.

Tale of the Three Lost Jewels continues Khleifi’s exploration of romance in the context of the First Intifada, but focuses this fantastical story on the innocent love between two twelve-year-old protagonists, Yusuf and Aida. The severe historical conditions of ongoing violence are palpable throughout Tale—the first feature film shot entirely within the Gaza Strip. The spatial and territorial enclosures of Gaza are repeatedly connoted throughout the film, as Yusuf lives in a fenced-in camp and his absent father remains in prison. The film revolves around Yusuf’s surreal quest to find three jewels from Aida’s family necklace that went missing when her family fled from Jaffa to Gaza after 1948, in order for Yusuf to be granted permission to marry Aida. Khleifi’s use of oneiric, almost magical realism-like sequences throughout Tale encapsulates the humanistic vision that underlies his filmic oeuvre, in which the actuality of violent borders is surpassed in the unboundedness of Yusuf and Aida’s follies and dreams. CINEMATEK’s restoration of these four discussed films by Michel Khleifi will not only contribute to the renown of celebrated works like Wedding in Galilee, but will further shed light on less considered but equally exceptional films like Canticle of the Stones and Tale of the Three Lost Jewels, whose fragmentary and mythic depictions of unresolved violence nonetheless lay claim to imaginative worlds of Palestinian resilience.