“I once read that I like to film bodies. No! But, if you choose someone, that person has a body. They have feet, hands, hair, breasts, ass — all of that is part of what is important,” said French director Claire Denis at the New York premiere of 2017’s Un beau soleil intérieur, a melancholic film that unspools itself with a unique handmade quality for the story at hand. In it, Juliette Binoche plays Isabelle, a single mother and artist, who cycles through multiple relationships with men who don’t necessarily complement her. It fulfills the platonic ideal of the romantic comedy while also being so much more, as the camera traces along like a visitor invited, treating its subjects with the same care and intimacy displayed by the above quote.

In Denis’ latest, High Life (2018), Binoche has once again returned, and this time, she is the manipulative Dr. Dibs, stationed aboard a spaceship where life sentence/death row inmate are ostensibly told they are setting out to harness energy from a black hole, yet the whole thing scans more as a suicide mission than anything else. Dr. Dibs collects the semen of the ship’s men, in hopes of inseminating the unwilling women aboard, and will go to great lengths to do so, exploiting with unprecedented force what Un beau soleil intérieur saw as intimate; the multiple romantic partners morphing into experimental subjects, reduced to mere vessels of sexual fluids. Along the way, blood and guts reign, as someone ends up bludgeoned with a trowel, and another is stretched like putty in the black hole itself.

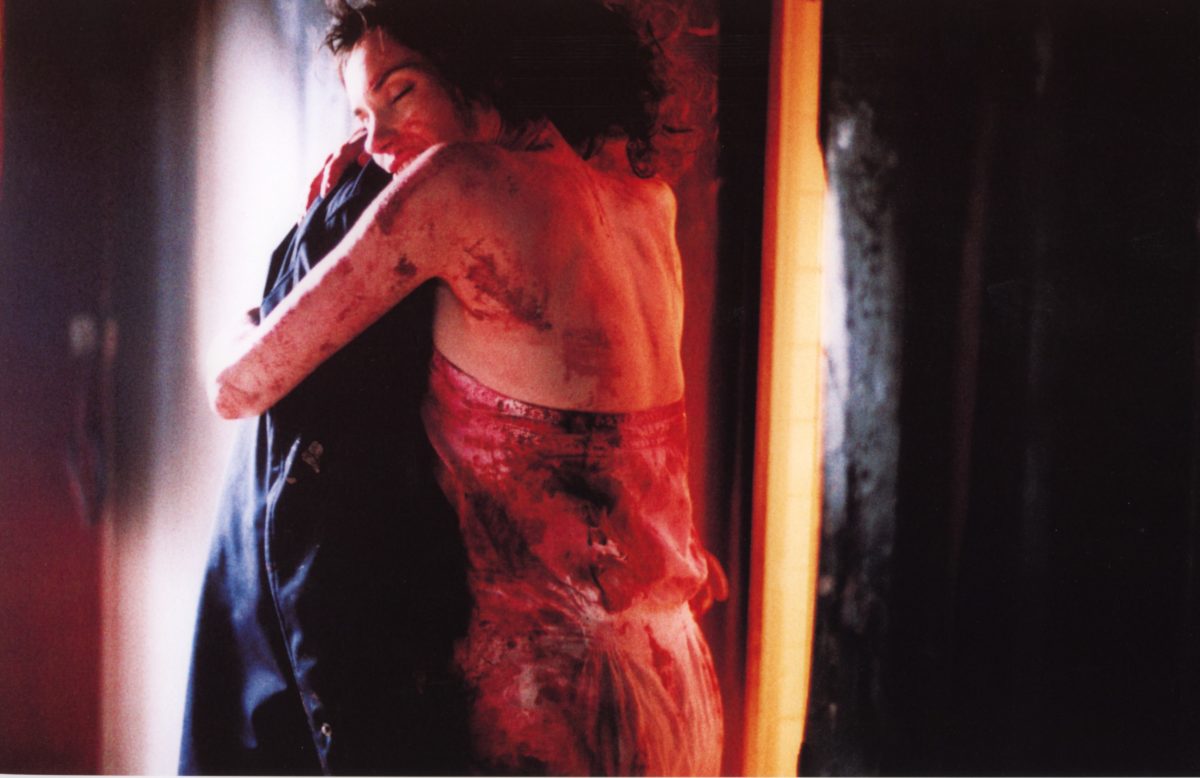

In a cinematic universe that has run the gamut from swooning romance to cannibalism, violence and intimacy have been closely juxtaposed consistently, almost always within the same film. Denis isn’t as much concerned with an unshakeable realism (as many of her misguided imitators are), but rather with personal space, which, “functions as a medium in which any narrative logic or meaning is suspended in favour of an oscillation of allowing and refusing tactility, pleasure and pain”Sebastian Scholz & Hanna Surma, ‘Exceeding the limits of representation: screen and/as skin in Claire Denis’ Trouble Every Day’ (2001), Studies in French Cinema 8:1 (2008), 5-16 . As viewers, we can extract narrative threads through our close proximity to the bodies in frame, though these bodies are equally prone to unpredictable gestures of either intimacy or violence. In the films of Denis, there exists, “both the pleasure of ‘touching’ and, at the same time, of destroying and invading the skin… often in one and the same image”Ibid., in scenes whose camerawork appears to be almost trapped within the events transpiring on screen.

Denis’ sense of world building has retained numerous hallmarks throughout her storied career, and this can lend one to believe that there is a throughline that runs through all her work; perhaps not strictly narratively, but undeniably thematically, and even allusively. Certain films feel as if they are memories spawned by the characters of another, there being subtle connections between each, even if it’s just a small cameo from Denis regular Gregoire Colin. So whereas the diversity of her filmography cannot be overstated, it is a diversity rendered through a series of well tread Denis motifs; these films aren’t wildly ‘different’, even if High Life (2018) takes place on the cusp of a black hole, and Vendredi soir (2002) concerns itself with a one night stand borne from a traffic jam. It’s versatility in which a director is consistently pushing to reach the perfect summation of what consistently preoccupies them as an artist.

Denis’ Nenette et Boni (1996) provides a succinct template for intimacy exploited, in how desire is refracted through a potentially dangerous dream logic. 19-year-old Boni (Colin) has an all-consuming lust for the neighborhood baker’s wife (Vincent Gallo and Valeria Bruni Tedeschi, respectively), to the point of harboring borderline stalking fantasies. The intimacy of the film is introduced as being less concerned with ideas of polite romance (faithfulness, healthy and consensual sex, affection relegated to a couple’s personal space), but with how intimacy itself can be manipulated, whether it be through a series of erotic dream sequences that seem to spill over into reality, or through coupling food and sex. There’s the baked products that recall human anatomy, genitalia included, and at one point, Boni violently kneads a piece of pizza dough, acting out his fantasies both verbally and physically, a scene which is humorous in theory, but uncomfortably voyeuristic in execution.

Trouble Every Day (2001) takes this ‘food as sex’ notion to a new extreme, isolating some of the more hallucinatory passages of Nenette et Boni, though now unmercifully brutal. In Trouble Every Day, carnality ultimately begets uninhibited cannibalistic violence. Shane Brown (again played by Vincent Gallo), and his old colleague and love interest, Coré (Béatrice Dalle), are infected with some kind of terrifying tropical disease in which any sexual desire comes coupled with the urge for literal consumption, “a bestial combining of human sensuality with animalistic reduction of the human body: as prey for wrenching, tearing, biting, clawing out eyes, lapping blood, and devouring flesh”John Tulloch, ‘Brutal Intimacy’, In: John Tulloch and Belinda Middleweek, Real Sex Films: The New Intimacy and Risk in Cinema (Oxford University Press, 2017) . Instead of conflating sex and horror for ‘sexy horror’s’ sake (like a typical slasher film), Denis’ film is markedly more mature, and attached to our own everyday, where sex can be violent outside the context of film, without the safety net of a clearly defined villain and victim; Denis pushes us to feel for Coré and Shane as much we do the murdered. Such an exploitation of intimacy sidesteps genre tropes, manifesting itself within the complexities of relationships that occur between ‘adults’.

Brown’s wife, June (Tricia Vessey), desperately wants to consummate their recent marriage, and almost gets her wish, though Gallo spares her, stopping sex short to masturbate, ridding himself of the desire that would result in her death (the hotel maid is much less lucky). Cannibalism abounds, but there’s also a breach of trust in a couple’s intimate life, where a kiss holds an insurmountable potential for betrayal both intimately and physically — Coré is married too, and her husband must allow for her to explore these dangerous desires elsewhere (as if some bastardized polygamous couple) while he searches for a cure — as harbored secrets are those of cannibalistic inclinations.

Vendredi soir plays out as an unexpected one night stand, though delivered with the same aforementioned mature complexity that concerns ‘adult’ relationships. Trouble Every Day pushes its characters into the impersonal arms of soon-to-be victims, a suppression of their love for means of safety, but Vendredi soir allows for an unexpected outpouring of love, following the same basic template of initial courtship laid out by its predecessor. The promise of anonymity is wielded more positively in Vendredi soir, in which an adulterous tryst retains as much pathos and compassion as a years long relationship. On the eve of moving in with her boyfriend (who remains a presence in mention only), Laure (Valérie Lemercier) gets stuck in traffic on the way to a dinner party — this being the Paris public transport strikes of 1995 — and in an effort to follow through on the radio’s encouragement to give rides to strangers during such a trying period, decides to pick up Jean (Vincent Lindon).

What follows is as much a display of tenderness as Trouble Every Day is of terror. Following Laure’s decision to cancel on her friends, and after a few fumbled interactions, she and Jean spend the night together in a hotel. There’s the lingering specter of Laure’s boyfriend, and her imminent move the following day, yet her time spent with Jean is stitched together so delicately and passionately, that the kind of promiscuity that intimacy-as-platonic-ideal scoffs at is made potently affectionate. Even just brushing by one another, or the purchase of condoms, is granted a kind of personal touch that is couched within straightforward romance: Laure and Jean present this dichotomy, where their romantic spontaneity feels nearly impossible considering the circumstances.

Trouble Every Day and Vendredi soir are also marked by the temporality of their titles. Trouble Every Day expresses how something seemingly so commonplace and mundane can be exploited the way it is, no matter how unintentional. Vendredi soir possesses an ethereality, where after close to an hour of presenting its characters somewhat impersonally, there’s an emotional investment which bubbles up to the surface, but then suddenly it’s Saturday morning, the night behind us already. Such differing formal qualities, when paired with off the cuff interpretations of intimacy, bring the two films even closer together as perfect complements.

Now, in the past two years, Denis released two more films in succession that follow a similar trajectory from compassion to violence, or vice versa. However, drawing parallels between Vendredi soir and Un beau soleil intérieur on the one hand, and Trouble Every Day and High Life on the other, would be beside the point. Once again, Denis has put out two films whose direct relationship is marked by their obvious differences, but whose similarities actually pull them closer together than they are apart, harking back to this previously discussed period of work from 2001/2, where it feels as if contradictory memories of the direct successor/predecessor, and other films in Denis’ oeuvre, have materialized from some cinematic waking dream.

Un beau soleil intérieur presents different relationships through different avenues for Binoche’s character of Isabelle; multiple men with differing backgrounds, all fairly flawed, though not without merit. This is then reduced to its basest elements in High Life, where the ever present intimacy of Denis is more corporeal, than romantic, intimacy seen as a necessity rather than anything else. The relationships Binoche’s Dibs has with the men aboard the ship is an exploitation of gendered sexuality for the purpose of experimentation, in which she ritually collects sperm from them, before inseminating the unwilling women, in an effort to have a successful birth in space (past attempts have resulted in the deaths of the fetus, and even their mothers). This workaround way of impregnation is an undeniable point of contention for some of the crew members: the women are even sedated at times so Dibs has free rein, and some of the men find masturbation in lieu of sex tedious, given the primal desire that cumulates in such a soul deadening environment, giving way to one of the film’s more brutal scenes, an attempted rape which results with the perpetrator stabbed through the eye with a shard of glass (as for Dibs, she chooses to satisfy herself in the ship’s ‘Fuckbox’, a room with a contraption bearing hand straps, seating and a large, sleekly silver dildo). However, her ‘baby making mission’ finally succeeds when she rapes a sedated Monte (Robert Pattinson), and uses his ejaculate to inseminate Boyse (Mia Goth), and soon enough, after death has claimed the majority of the crew, it’s Monte left alone aboard with his newborn daughter.

Claire Denis has said High Life is about, “…tenderness in space. It’s about trust, fidelity and sincerity”, which is what develops between Monte and his daughter Willow, despite the unfettered horror that has left lasting impacts on their everyday. Though set in space, High Life is not unlike 2008’s 35 rhums, which studied a father-daughter relationship in the vein of Ozu. Though the usual familial boundaries were a bit blurred, it is a film that presents a hallowed relationship as lovingly as it is always assumed to be, and found symbolism within moments of quiet. There’s the much talked about prevalence of the rice cooker, embodying the endurance of Lionel (Alex Descas) and Josephine’s (Mati Diop) relationship, or the ending itself, when Josephine dons a white dress and gloves, never specified if for a wedding or another formal engagement, yet still indicative of her own maturation and healthy distancing from her father.

Denis finds freedom in silences and negative space, not just in 35 rhums, but across her filmography; there’s no bold, moral driven depictions of infidelity, and no grand proclamations of romantic/sexual intent. In Un beau soleil intérieur, we cringe at the men who do make these statements, who do comment blatantly on how they’re cheating on their wives, finding romantic uplift in Binoche and Descas (another Denis regular) deciding to simply hold hands. Events simmer and pop at a spontaneous rate, rather than follow a linear development building towards the obvious climax, quite appropriate also for a film like High Life, where the silence of space is as loud as a trowel to the back of the head. With the almost invasive cinematography that Denis favors, Monte’s paternal love for Willow can be reduced to a flitting of the eyes, or a turn of the head. Denis stresses the importance of the body, and even as the source of High Life’s unsettling core, one’s physical being can easily convey assumed-to-be-outsized sentiments of familial loyalty.

Though there was not much of a relationship hinted at between Monte and Boyse — Monte himself choosing to lead a more monastic day to day on the ship — he looks at Willow within the context of her mother nonetheless, snatches of memory playing out on screen, like Boyse slowly floating in an anti-gravity chamber, her gaze pointed straight ahead, as if we are seeing her from Monte’s perspective. These moments are where High Life feels like a culmination, an expert blend of sexual exploitation and violence, and romantic tenderness, remaining as unsettling as Trouble Every Day but suffused with romanticism like Vendredi soir. The most intentional contact the two inmates have with each other may be the bloody scuffle near the beginning, but they end up mixing blood from respective gashes, as if their fate as unbeknownst parents was determined then. Though perhaps a saccharine compliment, Monte tells Willow of the beauty of her mother, and how she looks just like her. The same temporality that marked Trouble Every Day and Vendredi soir reemerges as Monte and Willow are the only two left alive in an environment where only 16 years have passed as 200 have back on Earth, saddling such boilerplate paternal statements with an unexpected emotional heft

“Why don’t you ever take me in your arms”, says Binoche as she straddles an unresponsive and sedated Pattinson, a clinically icky request considering what is about to happen. Despite the practically evil methods of Binoche’s witchy Dibs, taken just as a piece of standalone dialogue, this is a sentiment that is fluidly expressed across the four films. There’s June trying to stop the ever growing rift between her and Shane, the fact that Jean and Laure will probably never be in each other’s arms again, and for Binoche as Isabelle, the desire for a relationship in which intimacy and sexuality are one and the same, a simple request from otherwise emotionally stunted men.

When High Life ends, there’s the uncomfortable possibility of the father-daughter relationship having to develop into a relationship more so between man and woman, where the love and care they’ve displayed through their survival has rendered them a new kind of Adam and Eve. This knotty dilemma would only once again throw this whole argument back into discussion, but for now it can be noted that the characters of Denis’ films are always standing at the precipice of such malleable intimacy; it is up to them what they do next.