There’s something to be said for a happy ending. Watching the final embraces of the main cast of Wet Sand, second feature by Georgian director Elene Naveriani, brings a glimpse of sunlight to a heart frozen over after 115 minutes of aimless plodding through a seaside town. Entering with a dyed mullet and tiger print shirt, Moe (Bebe Sesitashvili) arrives in a conservative village on the Georgian coast to investigate the mysterious hanging of her grandfather, Eliko.

The mystery clears up rather quickly; Eliko was, like his granddaughter, involved in a same-sex romance, his with dapper café owner Amnon (Gia Agumava). As a television news insert declares, Georgia has recently replaced its ‘Day Against Homophobia’ with a priest-led ‘Day of Sanctity and Strength of the Family’—an edict that the townspeople seem to support—and the forced covertness became too much to bear. Moe’s reconstruction of her grandfather’s life progresses by narrative inertia more than by clever sleuthing. While such disconnection from the minutiae of genre elements often gives a movie space for expansion beyond them (as in, say, The Big Sleep or Wanda), the characters here maintain a strained sobriety throughout. Moe cremates Eliko and Amnon, following his understated death, by tossing a Molotov cocktail into the café with their bodies inside. Freed from its narrative, the movie can relax in its last moments: Moe meets a lover of her own; the two start a new café and invite all their new friends—a deep, genuine hope for Georgia rings through these tender scenes.

Were it not for the oddly-joyless script, Naveriani’s direction could provide enough intricacies to sustain the movie. Most scenes are composed in long, theatrical takes. Actors cheat out towards the camera and cross the frame with purposeful steps—or rather, purposeful-seeming, as their motions never seem to match with the rhythm of the scene, which combines with the overarching sobriety to strike a tone close to comedy. Languorous, sentimental shots capture Moe looking on as Amnon kisses his ex-lover’s dead body; isolated, it is pure cringe comedy, like Nathan Fielder’s out-of-step “I love you—again” in his acting treatise, ‘Smokers Allowed’, without the levity necessary to laugh.

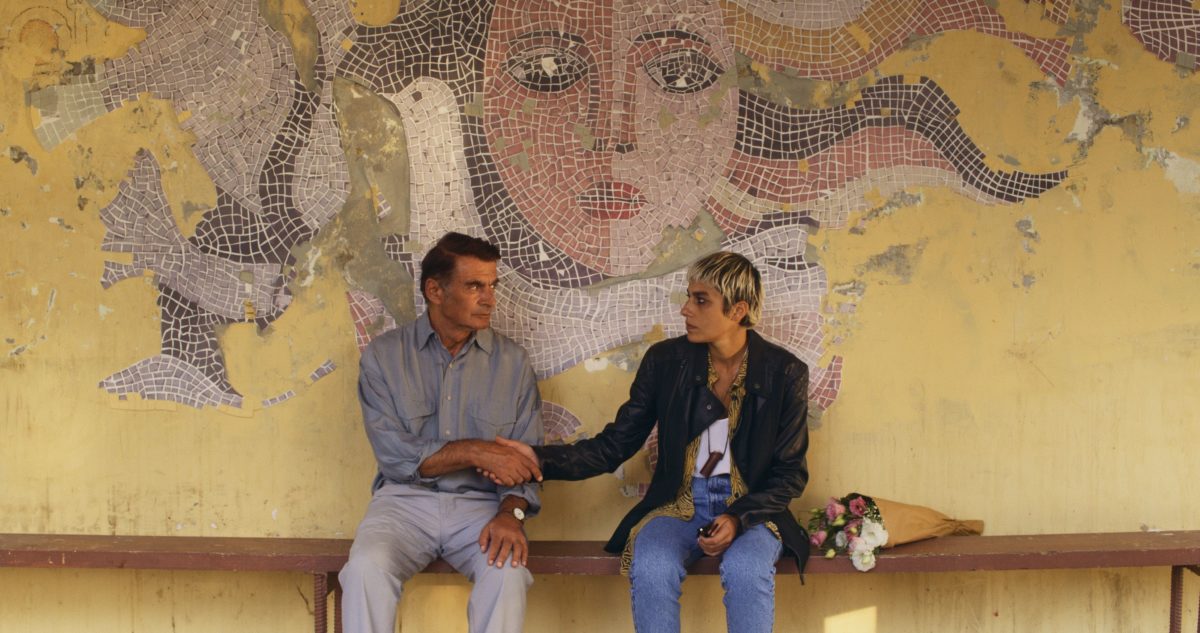

Even when he’s not smooching corpses, Agumava’s Amnon holds himself with one foot in the grave—hunched shoulders, hanging arms, and blank stare. After all, his other half has died, and his non-expression of grief rings true with both the universal confusion of death and with his learned subterfuge after his years of hiding from Georgian society. At times, his brooding figure evokes the zombie-like Ventura from his films with Pedro Costa; accordingly, Agumava received the Leopard for Best Actor at this year’s Locarno, known for its consistent relationship with Costa’s work. Like the Portuguese filmmaker, Naveriani chose to cast non-actors for her lead roles, and perhaps the biggest knock against them is that they seem professional. Where Costa’s actors exist as collections of their rough edges, Sesitashvili can appear smoothed-over, like a community theater player aching towards the big time. Wet Sand as a whole exists in this halfway point, on one side an over-slick mystery and on the other local tale from the heart; a step in either direction could be enough to elevate the material.