Technicolor and God (again)

Well, it did happen. And it was the perfect night for it too: clear skies, a slight breeze and a full moon flanking the Palazzo dei Banchi. Twentieth Century Fox Executive for Film Preservation Shawn Belston took the microphone from Gian Luca Farinelli and confirmed before the massive crowd assembled at the Piazza Maggiore what I wrote about in my previous blog: the print of The Thin Red Line we were about to see was as unique as they come, a Technicolor dye-transfer copy made as a gift to the director that only very rarely leaves the vaults. The result was a small miracle. The dye-transfer completely transformed the film, especially in the deep saturation of the blacks, making an already high-contrasty film (that Queensland light!) look like Caravaggio. The first scene between Sean Penn’s Sergeant Welsh and Jim Caviezel’s Private Witt, a confrontation set in the deepest holds of an infernal troop carrier, in this print becomes a re-staging of St. Matthew and the Angel. In the words of photogénie’s own Bart Versteirt – who was probably musing on Caravaggio’s self-portraits – you couldn’t stop gazing into the heavenly blue of the actors’ eyes … Tonally, the film was transformed at almost every level – the Melanisian scenes (shot on the Solomon Islands), filmed during magic hour, became a polyphony, a choral composed of the islanders’ dark hair and skin, the cerulean tones of the Great Barrier Reef, the purple skies and jungle greens of the Daintree Rain Forest. Again, CINEMATEK’s Nicola Mazzanti was proven right: Technicolor is God. [See our previous entry: Only Whoop Dee Do Songs. Bluebird Photoplays Light(en) Up the Cinema Ritrovato.]

At a technical level alone, the film more than confirms its status as the American masterpiece of the nineties: the orchestration between the majestically sweeping long-arm Akela crane, kept low to the ground, working like a dolly; the intricate sound mix, interlacing natural sounds with the actors’ prerecorded breathing, working together with other textural elements to create total immersion; the staging of the action so lucid that every single character beat is developed with utmost precision; the frame-perfect matching between panoramic shots of soldiers flanking the hill (clouds passing over the sun as if on command) and those totemic insert shots of bewildered wildlife gazing down at human folly; all these elements align to make the ‘Hill 210’ scene one of the most memorable passages in film history, an operational aesthetic that exceeds the logistics of the original military operation. The film is also a triumph of pacing and rhythm: its epic running time is primarily determined by the time Malick takes to linger in the quiet after the storm, both before and during the company’s leave (as I’m taking in the mix of shock, surprise and fear on the faces of Ben Chaplin, Elias Koteas and Dash Mihok, words come from another film I saw here, the 1977 Armenian drama Nahapet, about a genocide survivor who, having lost his wife and children, returns to his native village and is reunited with his sister in a desperate embrace; to bystanders observing the intimate scene his brother-in-law says: ‘Let them cry as long as they want; it makes them quiet, gives them peace’). The assault on the last remaining Japanese positions on the island is seen as a whirl of jump cuts, shredded material that could have made for another set piece, leaving more screen time for the contemplation of those weary faces, numbed but not yet without feeling.

That was the greatest surprise for me in this film I’ve seen many times before: how good the actors are, how well directed (most would never be better), and how straightforward the theme of the film really is: it’s a film about dying, about the precise moment and experience of death, about the fear of that moment and the protective barriers we build to hold that fear at bay (faith in a higher power, the idea that love is stronger than death), barriers that will turn out to be extremely porous – as Anne Wiazemsky’s Marie says to Walter Green’s hapless lover in Bresson’s masterpiece Au hasard Balthazar (seen here in a recent restoration): “La réalité, c’est autre chose.” Time bears heavily in this film, and the yearning for wholeness, whether in Witt’s transcendentalism or in Bell’s memories of his and his lover’s bodies flowing together, like water, made me think of Virginia Woolf’s To The Lighthouse – another metaphysical story set on an island – and Mrs. Ramsay’s great ambition to bring all things and people together. That ambition is thwarted by time, by death, by War, but in the end it is realized when Mrs. Ramsay is transformed in Lily Briscoe’s art: she becomes a tree, placed in the middle, to hold the picture together. At regular intervals in the film we hear a clock ticking, bringing us back to an early flashback of Witt’s mother dying, the moment when she ‘passes,’ curtains billow and he hopes/thinks he has seen something (is that young girl an angel or the mother’s younger self?). At the Piazza, in close proximity to the treasures of Italian Renaissance painting, gazing at the glories of Technicolor, we have seen something.

Piano Man

When we think of the great masters of cinema, it’s usually pictorial qualities that we think of, particular elements of mise en scène, striking framings, or innovations at the level of editing. This makes it harder to deal with comedy directors as great masters, unless they are striking stylists like Lubitsch or Keaton. In many cases, of course, especially in the silent era, the comedy director is also the star, which gives us a way out of the problem in that we can then talk about the genius of a particular film artist in terms of what he does as performer and the way the direction is geared towards allowing the fullest engagement with that performance. Chaplin is the obvious example, and his case also shows how aesthetic evaluation is often determined by the artist’s perceived humanism: Chaplin is a genius because he is a peerless comedic performer and because his mise en scène expresses universal human values (he makes people laugh, or cry, whatever culture or demographic they belong to). Jean Renoir, another great genius and humanist, who loved comedy, famously said about Leo McCarey that he understood people better than any other Hollywood director. The Renoir quote is reported in Andrew Sarris’ The American Cinema (1968); Sarris places McCarey in the ‘Far Side of Paradise’ category, right under ‘Pantheon’ directors like Chaplin, Ford and Lubitsch. But what exactly does it mean that McCarey understood people, and how, precisely, is this understanding expressed in his films?

The most obvious place to look would be those films considered to be McCarey’s most personal and deeply felt, which in many cases means those films that aren’t really comedies at all. An anecdote that has become part of McCarey lore is that when he won the Academy Award for best director for his screwball comedy The Awful Truth in 1937, he said that he had been rewarded for the wrong film, his much more personal Make Way for Tomorrow having failed to meet with any kind of acclaim that same year (Make Way for Tomorrow was the film that inspired Renoir’s ‘people’ quote). For McCarey, The Awful Truth was just another of those look-out-my-husband jobs he had been cranking out while he was working for the Hal Roach studios. His frustration at not being recognized as a ‘serious’ director is similar to Frank Capra’s, one of McCarey’s idols, or to that of the Joel McCrea character in Preston Sturges’ 1942 Sullivan’s Travels (a character based on Capra), whose ambition is to make ‘important pictures,’ relevant social dramas instead of merely entertainment. And then he watches the inmates of a labor camp engaging with Disney’s Playful Pluto …

There’s a tendency to be construed amongst graduates from the laugh factories of Roach and others, forever trying to move on from that period in their career towards more serious stuff, the kind of films that win Oscars: McCarey, Capra (a gag writer for Roach and a director for Sennett), George Stevens (a cameraman on Laurel & Hardy two-reelers) all fit the profile. But you could say about all of them that they did their best work in close proximity to their starting years, when they still knew how to apply some basic rules of popular filmmaking: make ‘em fast, make ‘em funny, and make ‘em so the star performers can shine. Make Way for Tomorrow is a great film, but The Awful Truth is a better-directed picture. Why? Because the performances in the latter film – Cary Grant, who found his persona in this film, Irene Dunne, never more charming and relaxed – except perhaps in that other McCarey picture, Love Affair(1939) -, Ralph Bellamy, never better at playing Ralph Bellamy, not even in His Girl Friday (1940), Cecil Cunningham as the indomitable Aunt Patsy – stick in the mind more than Beulah Bondi and Victor Moore, even if these character actors gave the best performances of their career under McCarey’s direction. If we follow Renoir and take it that McCarey understood people better than any other Hollywood director, I think we should change ‘people’ in that sentence to ‘actors’, or, even more specifically, comedy actors.

The actor is probably the most neglected part of both the filmmaking process and the critical reception. The reason why this is so is fairly obvious: for a director, it’s extremely difficult to make people do what you want them to do, to impose your will and ‘vision,’ when you know that direction always comes with the risk of players (who aren’t called that for nothing) losing their spontaneity, of losing their greatest asset which, in the Hollywood star system especially, is being able to be themselves in front of a camera. In the case of the critic, it’s extremely difficult to be specific, to write in great detail, about what it is that actors do, whether it’s the exact way they hold or move their bodies, say their lines, handle props, or the way charisma just oozes out of them. These are much more subtle, much more intangible qualities and characteristics than even the most fine-grained aspects of mise en scène. McCarey understood actors – he understood that for a performer to be at his best, a director had to find the right balance between freedom and control, between guidance and improvisation. This may seem obvious, but just about any director who takes his job seriously will tell you that it isn’t.

McCarey learnt all about acting from Charley Chase, a veteran of Al Christie’s Film Company, who was instrumental in changing the Hal Roach approach from slapstick to situation comedy. Chase was a genius, probably the most underestimated performer from Hollywood’s silent period. He was director-general of the Roach studios in 1921 before stepping in before the camera after the studio’s biggest star, Harold Lloyd, had left in 1923. His specialty was the ‘comedy of embarrassment,’ in which he usually played a befuddled husband whose inability to resolve the numerous Feydeau-ian coincidences and cases of mistaken identity both arouses our sympathy and makes us giddy with pleasure. Chase’s kind of comedy, taken from Max Linder’s appropriation of theatrical bedroom farce, but with so many precision-timed chases, entrances and exits that, at times, it come close to rivaling the architectural complexity of a Buster Keaton film (just look at the crisscrossing paths of Mr. And Mrs. Moose, unaware of each other’s presence in an almost diagrammatically laid out set, in what is probably Chase and McCarey’s crowning achievement, Mighty Like a Moose from 1926), requires two things: careful planning and tireless energy. The perfect balance between freedom and direction.

Chase taught McCarey that actors work best when they’re completely relaxed, when they feel that they’re working in an environment that’s friendly, appreciative of their talent and geared towards their skills (this is exactly what Harold Lloyd’s granddaughter Suzanne told the Ritrovato audience introducing a screening of The Milky Way). And McCarey was the great relaxer, fiddling at the piano, singing tunes, doodling, looking for the right mood, while the script was temporarily placed on the backburner. If Howard Hawks similarly got such great results from his (comedy) players, it was because he had learnt from McCarey – from whom he borrowed almost every single gag, before remaking The Awful Truth as a version of The Front Page – that a good performer is a spontaneous and above all happy performer, totally relaxed after a three-martini lunch. Another thing that put actors at ease was the idea of repetition and variation: the motivation for comedic legends like Lloyd, W.C. Fields, Mae West, The Marx Brothers, George Burns, Gracie Allen, Mary Boland, and Charlie Ruggles, to retry bits of business they had done so many times before, either on film or in vaudeville, is the same as the reassurance needed to convince stars yet had to make a name for themselves as comedians, Grant primarily, to do something silly: these bits belong to the patrimony of comedic entertainment, so it certainly can’t hurt to give them another spin. That’s why you can find that gag with the two suitors being given each other’s hats by mistake, a skit that goes back at least to a nineteenth-century vaudeville farce like Box and Cox (1846), in virtually every McCarey film from the thirties.

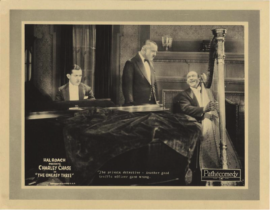

What McCarey brought to his actors is perhaps best illustrated by a case in point. One of the worst two-reel comedies that screened as part of the retrospective was the 1927 Should Men Walk Home? (the very title, with little relation to the plot other than the meet-cute that gets things going, illustrates the principle of repetition and variation at an industrial level; compare to Should Husbands Be Watched? (1928) and Should Second Husbands Come First? (1927) from the same period), one of the few McCarey films from the time that didn’t star either Charley Chase, Laurel & Hardy or Jewish curmudgeon Max Davidson. The stars of this film – a variation on the well-worn plot of thieves trying to steal expensive jewel at high-society party, a set-up as old as those Francis Ford/Grace Cunard serials and one tried with more success in another two-reeler that screened in the program, the Chase comedy The Uneasy Three (1925, in which Bull Montana does an excellent Lon Chaney) – are Mabel Normand, in ill health and close to retirement, and Creighton Hale, fresh off The Marriage Circle. The first reel of the film is a disaster, with unfunny business between Normand and Hale’s amateur burglars and house detective Eugene Pallette (‘Not stupid. He never got that far,’ says a typical Beanie Walker title) exhausting the patience of the viewer wishing for Charley Chase and Katherine Grant. And then something happens. The second reel starts with a surrealist gag that has Hale taking a dive in a fountain to retrieve the jewel. We then get an underwater sequence, followed by the resurfacing Hale posing as a gargoyle (in a row of three grotesques who all have his features) to fool the detective; as he sprouts water for an impossible amount of time, you can see how he tries hard not to crack up. He’s starting to enjoy himself.

The same thing happens with Normand in the following scene. The jewel has landed in a punch bowl and Mabel’s job is to upset and discourage any possible takers, including a befuddled Oliver Hardy. The scene, repeated with Hale, works like a slow burn, becomes riotously funny precisely because the gag is repeated again and again, excessive even in a situational logic. Hale curtly shakes his head in disapproval at Hardy’s umpteenth attempt to get some punch, the big man obediently returning to his corner, waiting for his next chance. Repeat. The funny business of repetition includes the rehearsal of the same framings, the camera staying at a leisurely plan américain distance to allow the actors full use of their bodies.

The difference between the two parts of the film is so great that you can only surmise that a better director than the one who started it took over midway and made it come to life. The film is generally seen as a McCarey comedy but his participation is uncredited. This was quite typical of the way Roach operated: ‘supervising’ directors like McCarey often didn’t receive any directorial credit even when they shot most or all of the film. But his fingerprints are all over Should Men Walk Home?: they point to an enormous skill with timing, tempo and reminding actors that what they’re getting paid to do is actually a whole lotta fun.