In 2018, the French label ‘Carlotta’ issued an excellent new 4K transfer of William Friedkin’s To Live and Die in L.A. (1985). Even though the film disappeared quickly from theaters in 1985 without making any waves, film scholars and critics alike now consider it one of the seminal underrated films of the 1980’s. One its few European defenders in 1985 was former film critic and artistic director of the Ghent Film Festival Patrick Duynslaegher, who praised the film for its decadent aestheticization of violence: “The film is a rhapsody of light effects, postmodern editing and perfectly composed images of male power and destruction” dixit Duynslaegher. Apart from being a film that does indeed fuse its abstract cinematic language with the ‘new figurative art’ of the eighties that could be found in the works of Eric Fischl and others, To Live and Die in L.A. is also one of the ultimate ‘Urban Thrillers’, films (usually ‘policiers’) that epitomize the foregrounding of the modern city (metropolis) both in their narratives as well as their formal language. The evolution of these ‘big city thrillers’ from 1970 onwards, shows a clear path towards a more and more abstract use of the city, running from the almost ‘documentary’ gaze of the seventies to the purely mental arena of the nineties and beyond. This tendency also reflects contemporary ideas about the role of the urban metropolis and the lives of the people who inhabit this modern city.

Dirty Harry and The French Connection: Rolling back Counterculture

It is an arbitrary choice to start this overview in the early seventies, as one could argue that the ‘film noir’ from the forties could also serve as a starting point. Going back even further, the literary work of Edgar Allen Poe and other authors from the 19th century might just as well fit the mold of a predecessor to the subject at hand, with its views of the ‘modern city’ that is both fascinating and fearsome.

There’s no denying the fact that films noir such as The Asphalt Jungle (John Huston, 1950) or The Naked City (Jules Dassin, 1948) have a strong focus on their urban settings and play off the contrast between rural America and the big city life. As Patrick Keating points out in The Dynamic Frame: Camera Movement in Classical Hollywood: “Hollywood Filmmakers (…) explored three distinctive aspects of contemporary culture: the dynamism of urban spaces, the seriality of mass productions and the convergence of crowded spaces that brought diverse groups of strangers together.” All these traits apply to the urban crime thrillers of the forties as well as those of the seventies, but as Nick Pinkerton mentioned in his article ‘What’s in a Decade’, written for the 2019 Antwerp Summer Film School: “The sixties and seventies had been the great ‘discover America’ period for U.S. films, as studios left the studio, on-location shoots became the norm (…).” This ‘discovery of America’ and location shooting also transformed the use of the ‘city’ in crime thrillers (and other films), marking the late sixties and early seventies as an ideal starting point. Moreover, there is a also a big difference between the characters – on both sides of the law – that figure in the world of ‘film noir’ or 19th century crime stories and their counterparts that emerge in the seventies. While the line between the proverbial ‘cops and robbers’ may be vague in the forties, there are still some thresholds and moral boundaries that are never crossed (in film noir’s case, under the watchful eye of the weakening ‘Hays Code’).

From the seventies onwards the template of the ‘private eye’ or the ‘tough cop’ resurfaces, leaving behind the forties associations of moral righteousness, although re-emerging in a new and altered way. These anti-heroes now bear the cultural ‘wounds’ of the sixties: the assassination of JFK, the cynical nature of America’s Vietnam politics, the horror of the war that penetrated the living room for the very first time… In Peter Yates’ Bullitt (1968), Steve McQueen’s character still bears some resemblance to its forties counterparts, but the ambiguous ‘heroes’ of Don Siegel’s Madigan (1968) and the films by Sam Peckinpah signaled the radical changes that were ahead.

Those changes manifest themselves fully for the first time in 1971, when Dirty Harry and The French Connection—two box-office hits—introduce a new kind of ‘hero’ into the mainstream of American crime cinema and with him, a different take on the urban reality that created this new figure. These new incarnations of standard ‘crime fiction’ characters not only inhabit the urban world they are part of, but also embody its values, morals and ideas. Both The French Connection and Dirty Harry are key films in a cycle of ‘big city crime films’ that incorporate this new approach.

The French Connection was the breakthrough movie for William Friedkin, who worked for television in the late sixties and directed the controversial documentary The Thin Blue Line (1966). Friedkin was part of a group of young directors who learned the craft and métier of filmmaking either by doing television work (as e.g. Steven Spielberg did) or by making ultra low-budget movies. (Francis Ford Coppola made his feature debut with the horror flick Dementia 13 (1963) and Peter Bogdanovich’s Targets (1968) only saw the light of day because Boris Karloff still owed legendary producer Roger Corman some days of shooting.) Another factor linking these young directors—who were to become the ‘New’ and ‘New New’ Hollywood generation—was a rediscovery of the cinematic language of both the European ‘New Waves’ and of the Hollywood studio directors from the 1940s and 1950s, whose ‘author’ status had been asserted by the French critics and theorists of Les Cahiers du cinéma. Friedkin’s main source of inspiration were the films by veteran director Howard Hawks—Friedkin met Hawks through the director’s daughter Kitty—whose fluent and elegant style he studied and applied to his own films, combining this approach with the almost documentary gaze at the urban environment that characterizes The French Connection.

Early seventies New York features prominently in the film, which stars Gene Hackman in a tour de force performance as the tough-as-nails cop Popeye Doyle, an inspector working for NYPD’s narcotics section. Doyle is an idiosyncratic, non-conformist detective, whose professional demeanor and existence have been molded and nurtured by the relentlessly bleak modern city he inhabits, an environment that makes it hard to uphold the ‘classical’ divisions between good and bad, right and wrong. This grim portrayal of the ‘Big Apple’ is much more than just the backdrop for the brutal action sequences; it is woven into the very fabric of the film’s visual and narrative patterns. The city as embodiment of the age of modernity (per Walter Benjamin) is an integral part of both form and content of The French Connection. Doyle himself can be regarded as a late descendant of Benjamin’s ‘flaneur’, a prototypical city dweller born out of the new reality of the modern city, a ‘product’ of the city, who looks at his modern environment in a new way, reading its cultural and formal aspects as a new kind of ‘text’ and absorbing and incarnating its new cultural meanings (Benjamin et al. emphasize the fact that this figure could not exist before the rise of the modern city and is thus completely linked to its existence).

It is out of this new reality that this city dweller, this ‘flaneur’ is born – someone who is able to open up to this new experience. Art historian Anke Gleber points out in The Art of Taking a Walk – Flanerie, Literature and Film in Weimar Culture that “products of industrialization redefine habits of seeing that prevailed in preindustrial societies and, in doing so, change the worlds to be seen along with the spectators who see them.” This idea is echoed by Jonathan Crary in Techniques of the Observer, which describes the evolutions of the 19th century as being “a radical abstraction and complete reconstruction of the optical experience.”

Put differently: industrialization, new mechanized modes of transportThe moving landscape that comes with the transport modes ‘train’ and ‘car’ has a lot in common with the 24 passing frames of the film medium (both in appearance and in the way it alters the perception of time as Gleber points out)—this idea is also reflected artistically by some directors, as the films of e.g. Abbas Kiarostami attest to. (the train and subway being the main symbols of these) not only changed society, they also introduced new ways of ‘looking’ and changed the ‘looking subject’, thus paving the way for the new medium of film, which combined all these elements. With the advent of ‘neuro art history’ and ‘neurocinematics’ it turns out that there is empirical neurobiological evidence to support this claim, as Warren Neidich states when he talks about ‘phatic images’: some images are constructed to draw our attention, which means they have greater influence on the process that shapes our neural pathways, and change the preference for certain images/stimuli/forms. These phatic images are mainly to be found in architecture (hence, the importance of the modern urban landscape) and of course in the images the film medium providesAs if the goal was to illustrate this point (which obviously wasn’t the case) The French Connection combines these ideas in its most famous scene: an elaborate chase between a car and a subway train that fuses all these elements in the medium of the moving image, which in itself was prominent in shaping the new ‘subject’ that lived in this post-industrialized world..

The urban landscape is pivotal in this process, as it is the crystallized and materialized version of this process, shaping—as Benjamin and others quickly realized—new ways of looking and perceiving that changes the ‘subjects’ living in the modern city. In the early seventies, these subjects were criticized by a reactionary reflex that gained prominence in American pop culture. In this way these ‘big city crime thrillers’ also reflect ideas that circulated in the culture that gave birth to them, illustrating what Gleber describes as the process of being able “[…] to read the history of culture from its public spaces and products.” This conservative and reactionary reflex manifests itself for the first time in a cinematographic form at the beginning of the seventies, but its echoes would resonate throughout the decade. It took the form of the mythological and demonized ‘metropolis’, a modern ‘Sodom and Gomorra’ that does not uphold the traditional ‘American Values’ (or how they are perceived) and was a clear illustration of the so-called ‘broken window theory’: when a single broken window in a street is not attended to, it doesn’t take long before the whole street degenerates. Crime is omnipresent in these (cinematic) big cities and—according to this concept—it will quickly run rampant throughout the US, infecting the hitherto non-afflicted areas just as well. The modern big city—a boundless collection of broken windows—is populated by figures that cause this constant degeneration and need to be combatted by equally extreme opposites, born out of the same city. In the case of Popeye Doyle, this extreme opposite is still more or less connected to the permissive sixties culture, six months later those ties would be severed by a movie that incorporated the same ideas in a more radical way.

Don Siegel did not belong to the new Hollywood generation and was already a veteran director by the time he directed Dirty Harry (1971). Still, it is remarkable how his films Madigan (1968), Dirty Harry, and to a lesser extent Charley Varrick (1973) and Coogan’s Bluff (1968) were instrumental in shaping the ‘big city crime thriller’ of the seventies. In 1971 Siegel had already released The Beguiled, a film that deconstructed the heroic image of its star Clint EastwoodThe symbiosis between Eastwood’s public and cinema persona is worthy of a study in itself, not since John Wayne has there been an American actor who balanced the ideological extremes of the country through the interplay of these persona to such a degree, Eastwood being a prominent member of the GOP—serving as mayor of Carmel-by-the –Sea, CA at one point—who still went against his party’s ideological stance in e.g. Million Dollar Baby (2004)., something that would become a mainstay in his career, alternately enforcing and deflating this image. Building upon this bifurcated ‘film persona’, the character of ‘Dirty’ Harry Callahan personified the reactionary impulses present in American society at the start of the new decennium. The cinematic incarnation of modern San Francisco that serves as Harry’s urban arena is, not surprisingly, a dark mirror image of the social reality that many large American cities faced at the time.

In Dirty Harry’s opening scene an unsuspecting victim at a rooftop pool is gunned down from afar. This brilliantly staged prologue clearly introduces the fear Dirty Harry exploits: the impersonal menace of the big city and the perception of an urban world that has fallen prey to degeneration and extreme violence. The cultural permissiveness of the sixties was perceived to have gradually given way to ideological emptiness—as diagnosed by Hunter S. Thompson in his Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas: A Savage Journey to the Heart of the American Dream (1971): “From the summer of love in ‘67 onwards, the great wave of the counterculture finally broke and rolled back.” It is this movement that both The French Connection and Dirty Harry (among others, but these films were the flag bearers) translated into the new formal and topical aspects of the ‘big city crime thriller’.

If Popeye Doyle in Friedkin’s The French Connection embodied the initial steps in this movement, Harry Callahan is its complete incarnation. Harry is the avenging ‘angel of wrath’—as Travis Bickle would be five years later in Taxi Driver (Martin Scorsese, 1976)—who has to “wash the scum of the streets” by any means he deems fit. It is no coincidence that Harry is no longer an ‘outsider’ in the city (as Eastwood was three years earlier in Coogan’s Bluff): Callahan is a figure that only could’ve been created by the concept of the modern big city. San Francisco is the symbol city of the counterculture of the sixties (a fact that Philip Kaufman also exploited in his 1978 remake of Siegel’s Invasion of the Body Snatchers), so it is not surprising that it is exactly this city that Harry has to rid of a killer who is also an out of control hippie who—dixit Patrick Duynslaegher—is “a monster that bears a peace symbol, but at the same time is out to destroy all human values.” James Hoberman probably offered the best analysis of the Dirty Harry character in his book Make My Day: Movie Culture in the Age of Reagan (2019) when he stated that “Harry Callahan was the personification of political reaction, the antidote to the permissive Sixties and Lyndon Johnson’s Great Society, a walking contradiction: the authoritarian who hates authority.”

While it is certainly not too far-fetched to also find a touch of subtle criticism on American foreign policy (i.e. Vietnam) in all of this, it is still mainly the fear and paranoia surrounding decaying urban centers that these films represent I am very cautious here not the use the word ‘zeitgeist’. As David Bordwell has said numerous times, “zeitgeist never turned on a camera,” meaning one-on-one reflections are difficult to assert, yet directors and scriptwriters live in the world and they pick up ideas from that world and channel them into their work through a creative process, so it’s not a stretch to posit that contemporary debates on inner city violence and law & order are being reworked here. in cinematic form. The symbol of the ‘metropolis’ or ‘modern big city’ is thus crucial for both films, much more so than for their predecessors from the forties. In the case of Dirty Harry, the whole film is interwoven with the ‘urban organism’, literally so, when the murderer transforms the city of San Francisco into the arena for a diabolic game of cat and mouse that requires the police inspector to make it in time to answer public phones throughout the city, in order to avoid the execution of a hostage.

Both films are representative for a tendency in the American crime film of the decade that emphasizes—with an almost documentary gaze—the existing locality of the cities in which they take place. The cultural associations that come with these places are also allowed to come into play, usually being part of the very fabric of the film.

I only look at two iconic examples here, but it is not too difficult to quickly compile a list of movies that perfectly fit this mold: Michael Winner’s Death Wish (1974), the main part of Sydney Lumet’s 70s oeuvre (Serpico, Dog Day Afternoon, Prince of the City, …) films by Scorsese and Walter Hill (The Driver, The Warriors) and countless others. Ideologically there are obvious nuances to be found in these films’ approaches, but the basic concept (the modern city with its excesses that need to be dealt with in new ways) is to be found in all of them. It is the advent of a new type of crime thriller that serves as a distant cousin to the ‘city symphonies’ of the twenties, avant-garde films that reflected upon the urban reality of the modern city, celebrating its vigor and energy. The same tropes that fascinated these filmmakers from distant decades however, are reflected here ‘through a mirror darkly’. The qualities celebrated in the city symphonies have turned sour in their seventies descendants. It is interesting to note that these new archetypes also appeared in the ‘Blaxploitation’ cinema of the early and mid seventies. Ernest Tidyman, who co-wrote the script for The French Connection, penned both the novel and the script for 1971’s Shaft (Gordon Parks Jr.), injecting the films with the same elements and ideas. However, as pointed out in an earlier text for photogénie, the protagonists in such films as Super Fly (Parks, 1972) or Cleopatra Jones (Jack Starrett, 1973) are as much a condemnation as a liberation: while they are indeed figures ‘of’ the urban environment (like Doyle or Harry) and ‘heroes’ in their own world, they are situated on the other side of the perceived moral line, still representing stereotypes about crime and the Afro-American community and the excesses of the city their white counterparts are out to combat.

At the start of the eighties, the depiction of urban arenas that in the seventies were marked by a gritty ‘realistic’ approach would become more and more abstract and give way to the new cityscapes of films such as Streets of Fire (Walter Hill, 1984) and To Live and Die in L.A. (William Friedkin, 1985).

Streets of Fire and To Live and Die in L.A.: Another Time, Another Place

The trend that marked the seventies certainly persisted into the early eighties (Sydney Lumet’s Prince of the City being a prime example), but as the decade wore on, urban cityscapes were depicted in increasingly abstract ways that dematerialized them and cut the ties with any existing locality.

Genre maestro Walter Hill was one of the pioneers of this new approach: The Driver (1978) and The Warriors (1979)—although firmly anchored in the seventies tradition—already employed excessive use of abstraction as far as the urban reality is concerned. His 1982 box-office hit (one of the few) 48 Hrs. equally balances the two trends, while Streets of Fire marked a radical step into pure abstraction on a formal level, altering the cinematic representation of the modern city. (Hill would later revisit both this style and a more hybrid form in such films as Red Heat (1988), Trespass (1992) or Bullet to the Head (2012)—I kindly forget 1990’s horrendous Another 48 Hrs.)

Throughout the eighties, the ‘urban jungle’ is still looked upon as some kind of modern ‘Sodom and Gomorra’ (cheap exploitation flicks like Savage Streets (Danny Steinmann, 1984) are graphic illustrations of this idea), but that urban hell is no longer rooted in the everyday reality of the big city, completely abandoning the quasi-documentary approach of the seventies films. Instead, the metropolis in urban crime thrillers is now an abstract world, inhabited by characters that are mere archetypes, completely defined by the urban environment that is their home, but lacking any clear ties to existing places or situations. Streets of Fire’s opening title reads “Another Place, Another Time”—signaling a complete abstraction, presenting protagonists that only make sense within the self-contained universe of the crime/action city thriller that may have some vague ties to existing cities such as Los Angeles or New York, but only exist within a mythology that was created by the genre itself. While The French Connection and Dirty Harry played off the aura associated with the city at the heart of the movie, Friedkin’s To Live and Die in L.A. only sports the name of the ‘City of Angels’ but recreates it as a purely cinematic entity that no longer needs any of the references attached to its titular ‘locality’ (or very little). The (criminal) world of the big city is still essential, but the concept of the city is reduced to its bare essentials.

Streets of Fire undoubtedly belongs to the most extreme examples of this trendI limit myself again to two pivotal titles, but urban action/crime thrillers such as Die Hard, Lethal Weapon (Richard Donner, 1987) or Cobra (George P. Cosmatos, 1986) belong on the same list. One of the few exceptions is probably Beverly Hills Cop (Martin Brest, 1984), which does again center on the existing reality and associations that come with the locality at hand. One could argue though, that Beverly Hills Cop is primarily a comedy and has little to do with the genre of the urban crime thriller of the eighties.: Walter Hill did some location shooting in Chicago, Los Angeles and New York, but the footage is integrated with the imagery that was shot at a large indoor studio set, an eclectic mix of ‘film noir’, ‘science fiction’ and ‘fifties Americana’. The ties with real locations are severed and no longer have a function—contrary to e.g. San Francisco in Dirty Harry—within the purely filmic construction of this new kind of ‘big city’. What matters now, are the filmic associations the city evokes. It is no coincidence that Streets of Fire is often referred to as a ‘big city western’ (a term also used e.g. for McTiernan’s Die Hard (1988), which does not elevate the abstraction to the same levels, but adheres to the same tendency): the archetypical tropes of the ‘big city crime film’ have reached the same status of abstraction here that those of the western had in the films of Sergio Leone and Eastwood’s High Plains Drifter (1973). One could also notice the fact that a similar kind of anti-hero preceded this process: the dark figure of Ethan Edwards from John Ford’s The Searchers (1956), is the ‘Western’ counterpart to the dubious figures in Dirty Harry, The French Connection, Taxi Driver or Paul Schrader’s Hardcore (1979). Once these self-reflective anti-heroes had played their part, they had—as was the case for the Western—paved the way for a process of abstraction that continued in the same vein, but detachedObviously there are exceptions to be found, eg. Charles Bronson was still basically repeating the same scheme every few years in Death Wish II, 3, 4 and the subsequent Dirty Harry movies were toned down versions of the original. the ‘big city crime film’ completely from any existing reality.

Streets of Fire takes this approach to extremes and combines it with truly virtuosic cutting and Andrew Laszlo’s brilliant photography, creating a purely cinematic universe that still holds up. The result is a milestone in the genre of urban action/crime film that failedHill later claimed that people often state that Streets of Fire is their favorite ‘Hill’ movie, leading the director to his standard reaction: “Great, where were you in 1984?” completely at the box-office and is still underappreciated as far as film studies or criticism are concerned, being a victim of a still reigning bias against genre fare.

A film that suffered the same fate and built upon the same tendency as Streets of Fire, was William Friedkin’s 1985 To Live and die in L.A. Friedkin directed—albeit with an interval that spans more than a decade—two of the seminal films in the genre, bookending the complete evolution of the ‘big city crime thriller’ in the 70s and 80s. The director’s own position was markedly different in both eras however: in 1971 Friedkin was one of the up-and-coming young talents of the ‘movie brat generation’ and was on the verge of finding box-office gold with The ExorcistTaking into account the adjustment for inflated ticket prices as BoxOfficeMojo.com does The Exorcist is still one of the ten most successful films of all time at the box-office. (1973). In 1985 however, the director, had suffered a string of box-office failures, most notably Sorcerer (1977), a film that was only recently—and rightfully—redeemed as a one of the director’s best. To Live and Die in L.A. would bring no change to Friedkin’s bankability and he would neverAs with Walter Hill, Friedkin’s later films were unsuccessful (roughly from the late seventies onwards), a negligible entry like Rules of Engagement (2000) notwithstanding. find the public success again that marked his early career.

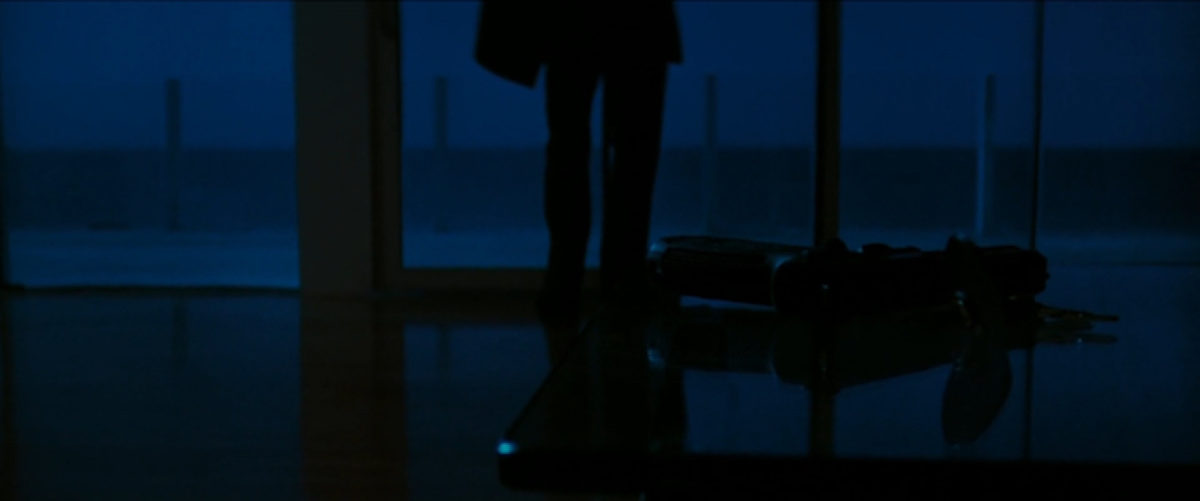

Nevertheless, To Live and Die in L.A. is a film that—to a degree no other feature matches—incorporates all the tendencies of the urban crime thriller of the eighties. It is intrinsically linked to its titular location, but that link is only superficial. As is the case with Streets of Fire, the actual locality and reality of Los Angeles have only a fleeting importance within the film. From the opening images onwards, the city is portrayed as an abstract space that is—as Duynslaegher rightly observed—reduced to patterns of light, movement and color. Strengthened by the aggressive electronic score by Wang Chung (the composers wrote the music on the basis of the script before any footage was shot, which lead Friedkin to the idea of filming and editing his images to the rhythm of the already available music) the film is a postmodern collage that fragments the concept of the ‘metropolis’ and reconstructs it as an entity that only consists of cultural references (filmic, but the web of referents is much larger, including architecture, painting and popular culture as well). The opening credits—undoubtedly among the most memorable of the decade—is an almost decadent ode to the power that money and its symbols have in the modern urban environment, which ends with the image of antagonist Eric Masters burning one of his postmodernist ‘new figurative’ paintings. (Strikingly, Masters is played by a young Willem Dafoe who also portrayed the gang leader in Streets of Fire, Dafoe at that point being known mainly for his experimental work with the Wooster theatre group that operated from a warehouse in SoHo.)

The opening combines the formalistic obsessions of a film that recycles art and film alike, appropriating elements from both figurative and avant-garde art, while acknowledging their adherence to the materialistic ideology of the eighties. Thus the limits between art, kitsch and capitalist logic are completely erased: the manufacturing of a batch of fake dollar bills has the same aesthetic quality as an art performance or the almost fetishistic gaze at objects and bodies.

The hyperstylized cinematography by DOP Robby Muller imbues the film with an almost ephemeral aura of beauty that also turns the city itself into an aesthetic object. Locality, characters and action (Friedkin tries to outdo his own car chase from The French Connection) are stripped of any referential relation to realityFriedkin opted deliberately for mostly unknown locations such as Slauson Avenue in South Central LA. and only possess meaning within the abstract universe of the film itself. The city that reflected certain social realities from the seventies films discussed above, now only derives its referential meaning from the depiction of cities in other movies—the simulacra from Baudrillard’s ‘hyperreality’ as a strictly (film) aesthetical object. The metropolis in To Live and Die in L.A. has become a purely filmic arena. Although throughout the decade some instances remain of the cinematic city’s referential relationship to reality, the shift towards the depiction of an urban environment that is informed by its previous cinematic representation is completed in the next decade, when directors will completely sever the ties with the urban arenas from the seventies.

This shift towards a more and more abstract depiction of the urban environment (and its history) put cinema in line with other visual art forms. Take for example the paintings of Gerhard Richter that recycle historic images; or the art of (street) photography, which approaches its main object of inspiration—the modern city—in a similar way from the late seventies onwards. As Steven Jacobs stated in his essay ‘Caleidoscopen met bewustzijn’, the public space that is the arena of street photography gradually eroded more and more, slowly erasing the “ideological substrate of street photography.” This resulted in the empty public and urban space that features in the street photography of the late seventies and eighties, which we can also recognize in e.g. the eerily empty streets in John Carpenter’s Halloween (1978) or Assault on Precinct Thirteen (1976) and which becomes more and more abstract in the cinema of the middle eighties. While at the start of the decade, the East Coast independent scene still adhered to depictions of New York that were firmly anchored in the previous decade (in films by Susan Seidelman, Lizzie Borden or John Sayles), in both ‘big city crime thrillers’ and other genres, the urban space becomes an abstract entity as the decade progressed.

Besides the changes in the depicted urban world, there is also an ideological shift to be found in the characters that inhabit this universe. Friedkin himself said in The Friedkin Connection: A Memoir (2013), when talking about To Live and Die in L.A., that he wanted to make a movie that was more in line with the “unisex style of Los Angeles in the 1980s” and deliberately worked with a technical team that featured more women than usual in key roles. According to Friedkin, the dazzling production design by Lilly Kilvert, who worked with Kathryn Bigelow—also an alumna of the East Coast scene—for The Loveless (1981) and Strange Days (1995), envisioned a more androgynous machismo than the one to be found in The French Connection. In this sense, the dubious anti-hero that William Petersen portrays, his nemesis Eric Masters (Willem Dafoe) and the hesitant cop played by John Pankow are all completely new incarnations of the stock characters from the seventies. These were also archetypes that ran counter to the reigning ‘heroes’ of the contemporary action film (Rambo: First Blood Part II (George Cosmatos, 1985), Commando (Mark Lester, 1985), Missing in Action (Joseph Zito, 1984), …), who embodied the politics of the Reagan era. The ‘complex’, brooding heroes of Michael Mann evolved from this mold (even John McClane in Die Hard is heir to this process) and the urban arena in which they operate would again be new and different.

As a closing remark on the decade, it is worth noting that there is also an economic process at work here. Nick Pinkerton’s text for the ‘Shady Eighties’ program at the 2019 Antwerp Summer Film School offers a perfect analysis of this extra element that fed the process discussed: “The great majority of American movies now seem to take place anywhere and nowhere, shooting in Los Angeles or New York (…) or otherwise asking an unidentified Shreveport or Toronto or suburban Atlanta to double for a better-known locale or play an unidentified Anytown USA …” Runaway productions that profited from financial benefits and the tendency to use any city as stand-in for another also contributed to this general move towards abstraction and would continue to do so—even to a greater extent—in the decade(s) to come.

Heat & Miami Vice: Mental ‘Grids’

The move towards making the urban space more abstract would intensify even further at the start of the nineties. The films directed by hyper-stylist Michael Mann illustrate this process in the most radical way. The brilliant crime thrillers Thief (1981) and Manhunter (1987) already showed signs of this approach, but in a series of ‘big city crime thrillers’ in the nineties and the new millennium, Mann truly started conceptualizing the urban arenas in a new way.

Heat (1995) is widely considered to be a milestone within the genre and had the added bonus of being the movie that paired screen legends Al Pacino and Robert De Niro for the first timeIt is widely known that although they shared top billing in Coppola’s The Godfather: Part II (1974) they do not actually share scenes in that film. in a face-to-face confrontation (this feat has been repeated a few times by now, with strongly diminishing returns). Heat is an intrinsically complex crime saga, that has more qualities on display than can be discussed in this text. Relevant to the topic at hand however, is the way in which the film built upon the tendencies from the previous decade and used them in a more radical way.

If the crime thrillers of the eighties gradually turned their urban setting into more abstract spaces, their nineties counterparts morphed these cityscapes into personal arenas, acting as a visual mirror of sorts, reflecting the mental states of the protagonists that turned from ‘flaneurs’ into seemingly aimless ‘wanderers’ (an element that is strikingly present in all of Mann’s films, most notably in the final scenes of 2004’s Collateral). The turn towards more abstract spaces continued, further erasing all links to existing cities and localities, as Mann did in Miami Vice (2006). The southern metropolis’s cityscapes are present in the visual layout of the film, but its cinematographic existence has more to do with the world of video art than with any urban reality, devoid as it is of any social or topical associations. The urban arena has turned into a purely visual object that only exists in relation to itself. If the eighties demonstrated a move towards Baudrillard’s simulacra, the next decade(s) entrenched themselves firmly into the ‘third phase’ of the French philosopher’s take on visual culture: signs and simulacra only have meaning in reference to each other and are shifting constantly—the urban arena in the ‘big city crime thriller’ has no ‘message’ or ‘meaning’ anymore in and of itself, it only exists as part of a genre and a cinematographic universe. In Heat this process of ‘dematerialization’ is on full display, as the city of Los Angeles is reduced to merely a world of abstract lines and shapes that engulf the protagonists and reflect their mental states. While To Live and Die in L.A. still allowed some ‘material’ elements into its cinematic universe—most notably the L.A. freeway—almost all of these recognizable elements have been removed from Heat (or Collateral or Miami Vice). What remains is an urban environment that only serves aesthetic purposes and contrary to the environment of the seventies no longer functions as a character in itself. In a way this is the final fulfillment of Benjamin’s idea of the modern city as an aesthetic display of modernity.

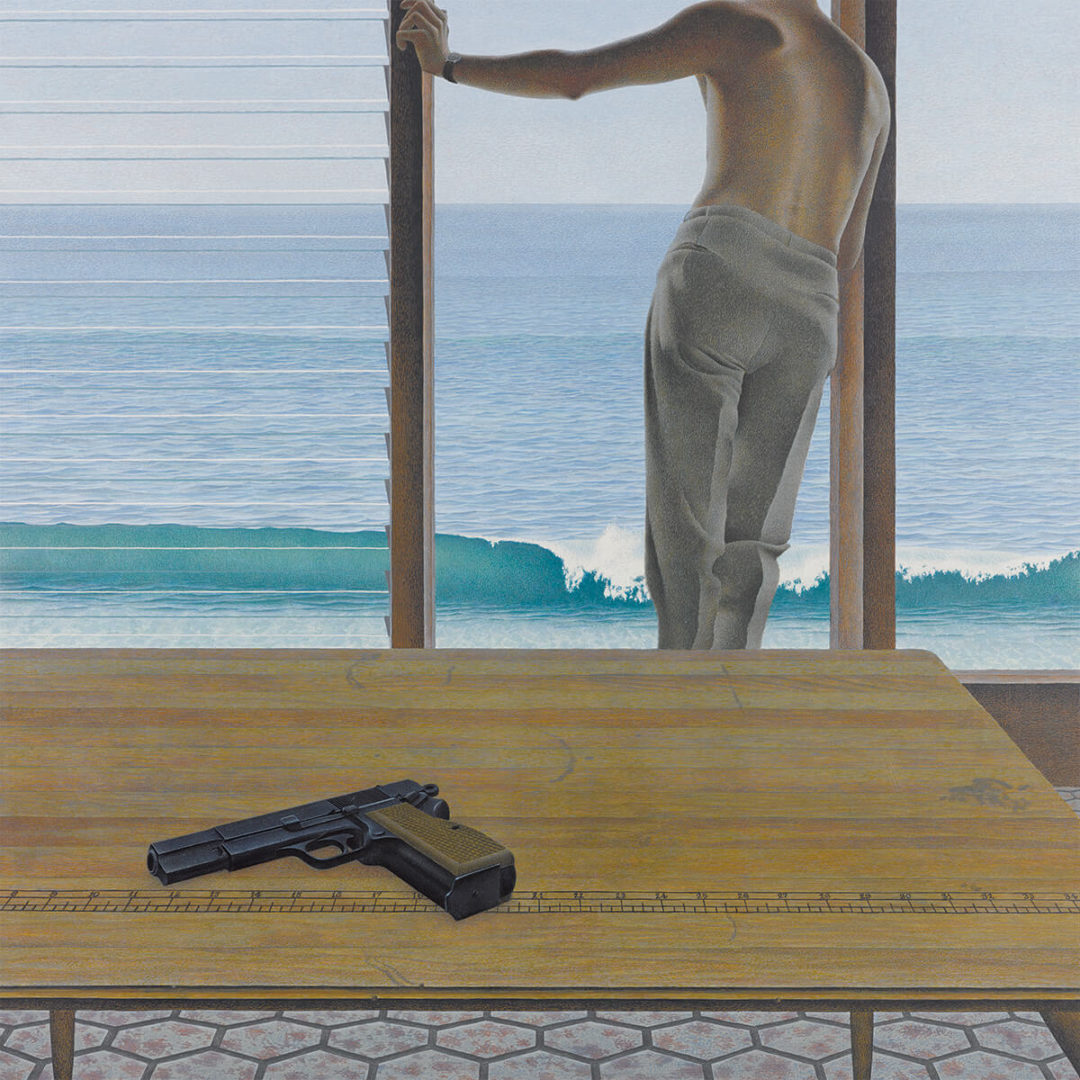

The same tendencies can be found in contemporary photography (Mann himself being a former photographer has always been attuned to this) and most strikingly in the works of Andreas Gursky, whose ephemeral images of late capitalist modernity—Times Square or Chicago Board of Trade II— are reminiscent of Mann’s work (and vice versa) both in composition and visual approach. In addition, Mann often uses direct references to other art forms as these images from Heat and the painting Pacific by Alex Cox can attest to. The films build a grid of referential meanings that merges with the imagined grid of the city.

It is no coincidence then that art scholar Rosalind Krauss, singled out ‘the grid’ as the underlying structure for all modern art (starting with the Impressionists in the late 19th century as Clement Greenberg suggested); a structure that is present in all of the works discussed above and that takes on an almost literal meaning in Mann’s underrated thriller Blackhat (2015). Blackhat is a dazzling visualization of the concept ‘grid’, as the basis for modern art, modern society and modern human relations. In Slant Magazine, film critic Jesse Cataldo called the film “a seemingly all-encompassing grid, expanding into a graceful visual motif.” Grids do indeed dominate this high tech city crime thriller (the movie opens with a visual evocation of a digital heist) that links causes and effects of seemingly random events that are actually structured by the virtual grids that connect them. Those grids are, however, virtual renditions of the human and cultural relations they represent, a fact that is rendered salient in the final confrontation, which presents the grid no longer as an immaterial entity but makes it tangible in the pattern of the local dancers at a Malaysian festival. We now experience the brutal bodily implications of the grids, a point that Mann already illustrates earlier by combining the high tech action with the corporeal brutality of inner city warfare.

Returning to Heat, it is clear that the film prefigures the urban environments of Mann’s later films in that the events are staged in an urban arena that is no longer anchored in reality in any way and only serves as a mental mirror of the protagonists and as an aesthetic cinematic object. This approach continued into the new millennium, as American ‘big city crime thrillers’ stripped their urban arenas bare and turned them into mere oblique reflections of the former grim city environments. A poignant exampleAs in the previous decades, examples that run counter to this trend can always be found, but as within any genre, there are always exceptions that diverge from the general tendencies. is S. Craig Zahler’s neo-noir Dragged Across Concrete (2019) which is set in an imaginary city that might be Los Angeles or Miami or any other filmic representation of a big city from the last two decades… The advent of full digital effects obviously has had its influence too, as real locations can be trimmed and adapted to suit any need the director or the art director have. It is the latest step in a process that started with the gritty realism of the seventies city crime thrillers—films with a clear link to the social reality of the city and to the political climate of their times—,continued with the weakening of this link in the eighties and finally arrived at total abstraction in the nineties and the new millennium.

References

Appadurai, Arjun (1996) Modernity at Large, University of Minnesota Press, Minneapolis & London

Benjamin, Walter (1992) The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction in Film Theory and Crticism, Mast, Gerald; Cohen, Marshall; Braudy, Leo (Ed.), Oxford University Press, Oxford

Bordwell, David (2017) Reinventing Holywood: How 1940’s Filmmakers Changed Movie Storytelling, The University of Chicago Press, Chicago & London

Colomina, Beatriz (1996) Privacy and Publicity – Modern Architecture as Mass Media, The MIT Press, Massachusetts

Cousins, Mark (2004) Story of Film, Pavillion Books, London

Crary, Jonathan (1990) Techniques of the Observer: On Vision and Modernity in the nineteenth Century, The MIT Press, Massachusetts

Duynslaegher, Patrick (1993) 1000 Films – Knacks Filmencyclopedie, Roularta Books, Zellik

Friedkin, William (2013) The Friedkin Connection – A Memoir, Harper, New York

Gleber, Anke (1999) The Art of Taking a Walk – Flanerie, Literature and Film in Weimar Culture, Princeton University Press, New Jersey

Jacobs, Steven (2005) Caleidoscopen met Bewustzijn in De Witte Raaf, 115, May-June 2005

Hoberman, James (2019) Make My Day: Movie Culture in the Age of Reagan, The New Press, New York

Keating, Patrick (2019) The Dynamic Frame: Camera Movement in Classical Hollywood, Columbia University Press, New York

Krauss, Rosalind (1979) Grids in October, Vol 9, Summer 1979

Neidich, Warren (2003) Blow-Up: Photography, Cinema and the Brain, Distributed Art Publishers, University of California, California

Pinkerton, Nick (2019) What’s in a Decade ? in Zomer Film College 2019 – Catalogus, Vlaamse Dienst voor Filmcultuur, Brussel