Authorship in both the cinemas of Marguerite Duras and Jacques Rivette is a richly volatile notion. First delved during years they put in as public, printed intellectuals, but especially alive when hashed out through their film work itself. It’s not only that both were critical of any received ways of making movies, but that they used their scepticism as a springboard for strange and vital new feints and forms.

This process is especially detectable with two films, each from relatively near the end of their careers: Le Camion (1977), directed by Duras, and Histoire de Marie et Julien (2003), directed by Rivette. Two mutated Kammerspiele—the latter also a tragic romance, while for the other, love is just one will-o’-wisp among many—that hold the unique distinction of being new attempts at unrealized projects, previously raised, or even began, by the same artists. In Duras’s case, Le Camion is not only a refashion, but a commentary and a proposed new ontology of cinema, as her film both imbibes yet distances itself from the film that it very nearly became. While for Rivette, the turnover was less expeditious. Histoire de Marie et Julien was a chance to dredge up, and actually bring to the finish line, a movie that he tried to make decades prior. Its failure dogged him ever since, with its remnants not only giving the revival its raison d’être and skeleton, but taking new shapes with the passage of time.

Le Camion

Le Camion was originally envisioned as a relatively simple two-hander. A lorry driver, to be played by Gérard Depardieu, ploughing his trade and his way through wintry Beauce climes, would have come across a hitchhiker. A woman, “déclassé” and “of a certain age”, to be played, possibly, by Simone Signoret. He would have stopped to give her a lift, the film from there lasting the length of their company with the drive as its frame and as its matter—the landscape, their conversation and the weak but persistent flame of a connection between these two very different personalities, constantly on the verge of flaring but never doing so.

The woman has possibly just escaped from Gouchy asylum, maybe not. She is talkative, telling the driver her own story but also what she thinks of other subjects, including, most significantly, the state of politics. Her own point of view seems to land on the left, but in an unorthodox sense, for she’s in agitation against any party dogma and denies a straightforward, proletarian allegiance or advocacy. He calls her reactionary, though it is not clear if this is meant a jab or a neutral statement. In his vast, silent listening and sparse, tentative questioning, he remains just as inscrutable as she, with her cloud of words.

The sudden restructuring of Le Camion came about for a number of reasons that could be variously called practical and personal; longstanding and ideological. Delays in casting the part of the woman—Signoret was unavailable—encouraged Duras’s already close identification with the character. The woman’s thorny stance was rooted in Duras’s own political development over the preceding decade. Since the ‘failure’ of ’68, her concept of a revolutionary victory was no longer bound up with the overturning of the capitalist status quo, and her disenchantment with the French Communist Party, and its increasingly dogmatic codes and demands, pushed her down towards a more individualist stance.This political underpinning puts the film into a possible communication, outside the remit of this piece, with the similarly Beauce-set Zola novel, La Terre. The bitter, post-revolutionary, realist novel on peasant life to Duras’ bitter, post-68, modernist film of an outcast.

She considered filling in the role herself. However, she doubted her own acting abilities, and this change in her political beliefs overlapped with a deep aesthetic quagmire that she had been wrestling with for many years. Before she took up the mantle of director, Duras was already an artist in her own right, with a significant critical reputation based on reams of novels, short fiction, non-fiction, plays and then screenplays, before she finally arrived at her screen-directing debut, La Musica (1967). By this time, she had thought long and hard about the limits of her control as ‘author’ or collaborator, and how that varied depending on the conditions of the different media she worked in, and additionally the different roles she was occupying within those forms.

The widely different capabilities and functions of the word versus the image also troubled her. Duras harboured a deep suspicion of the image, of a reverse Flusserian character.

I don’t think the image can ever replace what I’ve called ‘the indefinite proliferation’ of the word.https://www.theparisreview.org/blog/2020/10/27/cinema-hardly-exists-duras-and-godard-in-conversation/

She stated this in dialogue with Godard, who would seem to be her perfect opposite, as an artist who “hates the text”, enraptured by images, and has taken them as his life-long métier and preoccupation. Throughout the 1970s he was the militant, fronting a collective, while she was turning in on herself. And yet there is common ground, as two of cinema’s greatest sound artists and reconcilers of different tendencies.

While armed with her reservations, Duras was still drawn to cinema, not repulsed. Unlike Bertolt Brecht, when he first began to engender his ‘non-Aristotelian theatre’, she was not an artist endowed with a radical’s purity, or as Raymond Durgnat would frame Brecht’s case, less kindly, a radical’s secret snobbery about ‘bourgeois’ forms and his oversight over their hidden depths and flexibility.

Though you could accuse Duras of the same blind spot with her sweeping reduction of most of narrative cinema, she does not entirely fit Brecht’s bill when it comes to her own artmaking. Like how her rejection of the classical novel did not lead to her refusal of the written word, or even the ‘bourgeois’ form of melodrama. Instead, she ran the form and genre through an aesthetic opposite to the classical and its successors’ “over-describing”—in other words, ‘representation’—which she saw as an unwillingness to leave to the imagination. By pinning down and explaining people and places according to no uncertain terms, it put the reader in a stranglehold of stunted meaning. A criminal state of affairs for an artist who unrelentingly investigated the persistent, often traumatic, instability of direct experience and memory. And so, she opted for obsessively elusive, diffusive, and permuting descriptions. Constant revision over setting in stone. This is most evident in the two major cycles which overarch her career: India Song and L’Amant, in which one scenario or one cluster of characters and images is repeatedly revisited and altered, transmedia.

For Duras to continue to make movies, she needed to throw off the primacy of the cinematic image, which she saw as the standard bearer of representation in the 20th century. This hinged less on its utter renege through flight into abstraction, than on the obliteration of the actor as its keeper and a re-ordering of cinema’s relations. Conventionally conceived with the image on top and underneath it, sound is still to this day the least utilized of cinema’s senses. She instead flipped this order. As the critic, professor and close friend of Duras, Annette Michelson, once stated, Duras’s ingenious conception was that if you “change the relations between sound and image, you have something new.”

This came to its first, full fruition with her film India Song (1975) with its ‘sound-off’ aspect. The actors move little or not at all, and do not speak on-screen, but we hear their voices on the soundtrack engaging in dialogue that corresponds to the scene. There is a further splintering of the image’s temporality and spatial dimensions, because the characters also speak about the scene, not just within it, but in reflection from a future point, while also contending with other viewpoints as additional characters, not present in the image, chime in. Duras was so flush with her re-discovery of ‘proliferation’, through soundtrack and screenplay both straying from and expanding the ‘definite’ image, making it soluble, that it inspired her to craft a sequel or companion film. She took India Song’s soundtrack and aligned it to a whole new set of images, with Son nom de Venise dans Calcutta desert (1976).

Le Camion is the next step in this progression. As a film of two, interweaving halves, it is a cinematic analogy to what Duras once said about writing, that it is like the parallel between the reflection in the mirror and the object reflected. The object, the old film, remains but stripped to recurring scenes of the lorry. This elemental, documentary mass, with its occupants obscured, drives through real countryside and towns, down back lanes and round roundabouts. Its journey is accompanied by diegetic sound, like that of traffic and of the landscape it’s traversing, as well as the non-diegetic and commentative, such as music—specifically a jaunty excerpt from Beethoven’s Diabelli Theme—and snatches of Duras in voiceover; Beethoven and Duras being the only two elements that explicitly straddle the divide.

The other, interspersed part of the film, the reflection, or the film made new and annotated, takes place in the reading room, or ‘the darkroom’, of Duras’s home. Seated at a table across from each other, each with a stack of papers that we gather is the outline of Le Camion, Duras and Depardieu proceed to read through and around the film. They give a description of the lorry and its itinerary, describe the outcast woman, the driver and the conversation and air between them. Like the supposed ‘on-screen’ conversation, they veer into abstraction and politics, and occasionally trade lines of dialogue. Duras does the vast majority of the reading/talking, with Depardieu, less familiar with the text, serving as a kind of auditor, querying her about the impulses and personalities at play.

What makes the film so complex, as it performs this curious dance, is the many ways each of the two sections mirror and interact with each other, rather than enacting a one-way, single functioned relationship where the dearth of plot and identifiable human figures in the lorry scenes are blanks to be filled by the chatter of the reading room scenes.

Duras and Depardieu’s discursion is not a close, sequential readthrough of a shooting script, but an amorphous dialogue caught up more with the themes and sensations that could encompass or surround the film, and therefore actually incorporates all these possibilities. This curated inconsistency is performed verbally in a constant, nimble switching of tenses, between the present and the predictive. Many times Duras clarifies in clear, hard terms, and asserts the desire to be received and understood, asking Depardieu, whether he can “regarde?” after a recitation. She also could be construed as the double, the origin and the expansion, of the woman she has written, not because she reads her lines exclusively, or the shared political alignment that is alluded to but never explicit. Rather, the dynamic between the two on-screen is measured out, in both how the verbiage is divided and the tension-drawing rhythm to their speech, to the ambiguous tension between the pair that exist only in their recount and in our heads. Any exact comparison is discouraged, however, in how the dialogue is as tentative as it is declarative. There are plenty of “peut-êtres”, abruptly brief descriptions, and instances where Duras admits no knowledge of what she has ostensibly conceived.

These misalignments and alignments are represented visually. The former in the distinct nature of these spaces, and the latter in a constant, shared kinesis. A sense that the whole film, even in its sedentary scenes, is travelling. The lorry trundles on and on, while Duras and Depardieu’s reading progresses from night to day and then to night again. Little to large shifts in angle, lighting and the props that litter the room and table are enacted with every cut-back, in tandem with the perambulations of their articulated subject.

This experimental intertextuality renders both strands as intensively speculative zones and objects, elegantly mashed together and feeding off each other in order to not just make one unified film, but to pluck and raise the twisted stems of a multitude of alternatives. Duras herself, in an interview accompanying the published screenplay, The Darkroom, compared this result to a folk form like storytelling. A reminder that though these ancient, popular forms are often labelled as traditions, this is a misnomer. That mouldy old term suggests the folk aesthetic is an unyielding catechism, rather than a collective, popular and populous play of creation using open models. Duras reignites this freedom and ambiguity, for herself and beyond herself, in a realm of more definite authorship, as well as for an age of powerfully indeterminable images.

Histoire de Marie et Julien

While Duras sought the excision of actors and acting—achieved to a level beyond even Le Camion with her follow-up, shorter works, Cesarée (1978), Les Mains négatives (1978) and the Aurélia Steiner diptych (1979)—Rivette doubled down on the primacy of acting, while seeking for it a new stage.

Histoire de Marie et Julien has its origin in the most turbulent and experimental time in Rivette’s career. By 1968, this former, bellicose pointsman for classical auteurism, who had only recently made La Réligieuse (1966)—where his presence as a director was a controlling one, out to craft a closed circuit formalism, precise within an inch—had changed his tune. Inspired by a wide of range of influences that were extra-cinematic—psychoanalysis, underground theatre, his editorship at Cahiers (1963-65) where he grandfathered its successive, most militant era by commissioning articles that were explicitly Marxist or of a semiotician’s bent—to the cinematic, with independents such as Jean Rouch, John Cassavetes and Shirley Clarke. All of this pushed Rivette at the end of the 1960s to invigorate his cinema. His new, multipronged aim was to combine non-fiction and fiction, set frameworks and chance, to discover a new cinema, where the sign and aegis of the director would mingle and even be superseded by the communal ethos of improvisation and a greater agency placed on other collaborators in general, but on the part of the actors especially.

In 1975, Rivette reached for an apex when he conceived of a series of films, initially called Les Filles du feu and then Scènes de la vie parallèle, that would utilize a more rigid narrative construction and recognisable genre elements compared to the near-totally improvised behemoth, Out 1 (1971). Regardless of the more stable base, this represented a venture into unknown territory. He sought “to discover a new approach to acting in the cinema, where speech, reduced to essential phrases, to precise formulas, would play a role of ‘poetic’ punctuation. Not a return to the silent cinema, neither pantomime nor choreography: something else, where the movement of bodies, their counterpoint, their inscription within the screen space, would be the basis of the mise-en-scène.”http://www.dvdbeaver.com/rivette/ok/lesfillesdufeu.html

Into this miasma he also threw an element of live and exploratory musicality, with each film featuring live performers who would be playing in almost every scene, off-the-cuff, in reaction to the movements and mood of the actors. The formal construction of the film would then be like a three-way dance of live and lithe elements, of William Lubchantsky’s camera, whatever musician, or musicians, playing and the actors’ bodies, with the latter given the most authority out of the three. Underpinning this arrangement was the scaffolding and safeguard of Eduardo de Gregorio, Marilù Parolini and Rivette’s scenario, with Rivette’s mise-en-scène and Nicole Lubtchansky’s cutting providing the silent arbitration and intervention.

Each film would be narratively self-contained and correspond to different genres; the ostensible first film, Marie et Julien, would have been a tale of star-crossed and doomed lovers, “where [the mise-en-scène] will function as an element of dislocation and strangeness within a dramatic construct still following the rules of romantic fiction, by way of the fantasy/horror film and the musical.” While the 2nd and 3rd, and only completed films in the series, Duelle (1976) and Noroît (1976), are a crime story and a swashbuckler, respectively. The last film, also never made, would have been a full-blown musical, starring Anna Karina. Additionally, the other carry-over element, other than this overarching stab at a new form, would be fantastical. The mercenary presences of celestial goddesses, or phantoms, inspired by Celtic myths.

Due to scheduling necessities, Duelle and Noroît were filmed first, with Rivette then leaping back to Marie et Julien, which was to star Leslie Caron and Albert Finney in the title roles. However, the enormous amount of energy and pressure required to pull off two of these complex gambles within “a short burst of time”, never mind all four, was too much wear and tear on Rivette’s part. Due to reasons of “nervous exhaustion”, the film, and the remainder of the series, was cancelled after just two days of production.

While convalescing, Rivette would edit and release the two films he wrapped, and once recuperated, attempt to put the series to bed with an epilogue of sorts. Merry-Go-Round (filmed in 1977 but released in 1981), another blighted production, is a captivating experiment but it gave Rivette neither the closure he sought, or a way out to new artistic pastures. The sublimely fiddle-footed yet melancholic La Pont du Nord (1981) would be the film that would round off this twelve-year period, while utilizing the Marie and Julien names and dynamic, though not the exact characters and story per se.

The part-failure of Scènes de la vie parallèle and in particular, the abandonment of Marie et Julien, would be what Rivette would deem his “one true remorse” as an artist. It haunted the filmmaker, who repeatedly tried to revive it, with Caron and Finney again and then Caron with Michel Piccoli, Maurice Pialat, or even himself. All intriguing prospects but none came to fruition.http://www.lolajournal.com/6/rivette.html

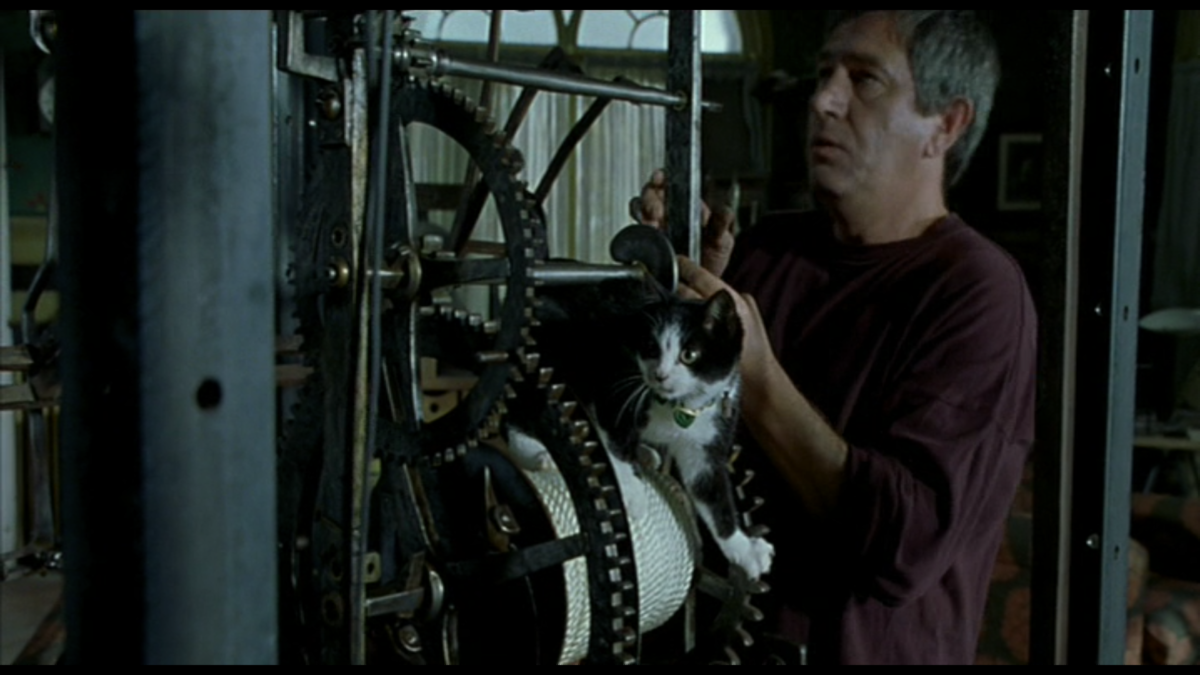

His luck came through in the new century, when Histoire de Marie et Julien finally emerged. It stars Jerzy Radziwilowicz as Julien, a freshly wounded bachelor, and a professional repairer of old church clocks. Julien has decided to spice up his trade and loneliness with a side gig as a blackmailer. He is in possession of various documents which he thinks might intrigue Madame X (Anne Brochet), for they include evidence of her crooked dealings as a silk trader. Though the more profound and disturbing artefacts relate to the suspicious circumstances surrounding the death of her sister, Adrienne (Bettina Kee). This situation is complicated with the arrival of Marie (Emmanuelle Béart) into Julien’s life, first as a literal dream, then in ‘reality’. They soon become lovers, with Marie moving into Julien’s creaky, old house, where they live with his cat, Nevermore. She too is burdened with the past, which is steadily revealed by her involvement in the blackmail and her strange fascination with an empty room upstairs. Both Marie and Julien begin to face the improbable facts, that the spectre of her tortured history might make their life together a painful impossibility.

If this film is watched while mindful of its origins and the other productions with which it was originally intended to link hands, the transposition of Rivette’s cinema, from a highly collaborative, free-wheeling affair to a more circumscribed object, is stark. The 35mm cinematography is often classically composed and the camera’s movement more deliberate, with the steady and tensile pans and tracking in and out carving a very different rhythm than what drives Duelle and Noroît, where the camera is reactive, skirting and loping. An active participant to its descendant’s patient and distant observer. Noroît also contains a brief but powerful burst of format experimentation, during its climatic sequence, or final “paroxysm”, with the periodic implementation of silent, black and white 16mm and crimson-filtered footage.

Music is a very prominent and expressive aspect for the series’ thesis and its surviving duo, and yet it is almost completely absent in the newer film. In its place, and instead of the daring use of direct sound that was another now bygone method, there is a minimal but minutely constructed ambience. These murmuring patinas of ticking clocks, birdsong and children playing have a naturalist base, as most of the film takes place in this clock-fixer’s suburban abode, and yet exude an eerie affect. They encase proceedings in an aura of stalled time, of happiness and vivacity being distant entities that still tug at these characters as they meander through a very depopulated, sluggish and hushed-up world. From the echoing, creakiness of Julien’s home to the supernatural realm, contained and decorated like a cross between the interdimensional, halfway houses of Twin Peaks (1990-92) and Fra Angelico’s sacrosanct compositions. It is an atmosphere that is very different from the often hypnotizingly paced but far more flamboyant, even hysteric, air of Duelle and Noroît.

Marie, Julien and company instead seem to be living in a purgatory. In the psychological sense, expressed in Julien’s distracted manner and his bookended admissions that life offers him little, nevertheless he lives on because what choice does he have. And literally too, with Marie’s half-way existence and deep trances, where behind her frozen façade and suddenly mannered movements and diction, there is the unexpressed rendering, and rending, of unresolved agony. Both characters, throughout the film, get caught up with a specific task that is productive in a perverse way, since it involves them both toiling, half-knowingly, towards oblivion, or at least the maintenance of their rut. For Marie, this task is the recreation the room of her trauma, for Julien it is working away at his clocks, making sure they don’t ‘limp’ while he limps away himself.

Suiting this deep melancholy, the performances in Marie et Julien are naturalistically minimal. Radziwilowicz is wonderful with his shrugging, shambling body language, playing the macho hangdog too easily given to defensive shows of apathy or annoyance. When he is blindsided, he breaks, revealing a frank awkwardness and vulnerability that is deeply moving. Béart is equally good at making her enigmatic presence, the phantom lover à la Kim Novak in Vertigo, both stylized and soulful. There is a kinship in how she moves and her pentameter in scenes where she is possessed, a conduit for an incantation in Irish, or a premonition in French, and the intimate moment where she recounts the aftermath of her previous lover’s death.

They are two very introverted performances. Their choices localized to, generally speaking, much less overt gestures and patterns, compared to the wild, unpredictable physicality of their antecedents. This is where it is disingenuous to pin every change solely on Rivette’s trajectory, to not consider the generic expectations of a tragic romance and the particularities of Radziwilowicz and Béart and their performance styles, circa 2002, versus what Caron and Finney would have brought to the project in the mid-1970s. Though other artists on the production, like the Lubtchanskys, may have been returning, writers Pascal Bonitzer and Christine Laurent were new to the material. They wrote the screenplay in a previously established method of writing during the shooting, scene by scene, day by day, with no significant pre-meditation. And yet a key difference is that actors were expected to learn and say their lines as written, with no involvement in the writing process unless they had a significant objection or suggestion.

This method—in part—attests for the low-key but still loose performances, and would suggest a more controlled state of creation, and yet this remit, for the actors to intercede when they really feel they need to, is more than just an ethical safety net that affected a handful of lines. In an interview, Béart stated that the sex scenes were a component that Rivette initially wanted to elide altogether—sexualized nudity being a rarity in his work—but she and her on-screen lover demanded their inclusion.Porton, Richard & Béart, Emmanuelle. ‘Acting as the Joy of Discovery: An Interview with Emmanuelle Béart’. Cinéaste Vol. 29, No. 1. Winter 2003.

This decision was fundamental and would not have been conceivable if the increased authority of the director that marks Rivette’s late period was a Langian absolute, rather than a flexible arrangement. The carnality of these scenes both relieves us from the sombreness that flows throughout the rest of the film, and accentuates the slow-burning heartache. Sex for them needs to be very orchestrated, like a miniature play, to suggest a concerted effort to pierce the veil of grief and depression and erase it with full-bodied fiction. As they fuck, they recite, duet, intense fantasies of a BDSM, earthy and mythological nature, combining physical closeness, logos and make-believe in an attempt to propel themselves out of the pit into a new liberated space, defined by assertive, not dulled, action and emotion.

There was an additional avenue of chance, stemming this time from within, rather than against, the writing process. Though there was no old screenplay to repurpose, Bonitzer, Laurent and Rivette could use the original project’s notes which had become gnomic out of context, and therefore newly inspiring. This is where the integral narrative device, and towering symbol in a film riven with powerful gestures and acts of rehearsal, ‘the forbidden sign’, comes from. Written down in the margins, in 1975, by Rivette’s then assistant, a young Claire Denis, with the annotation, “not to forget”. Ironically both her and Rivette had indeed forgotten its original meaning, so it had to be reinvented with its new meaning the inverse of Denis’s command.

There was also scribbled mention of a ‘talking cat’, which led to the ‘character’ of Nevermore, who is very much a non-verbalizing, flesh and blood feline, and yet he is denoted as a púca, or a zipped mouth Cheshire Cat. A mischievous creature that can transcend the planes of existence, and so pushes the narrative forward through his separate interactions with and leading of Julien and Marie. He is also the aleatoric ghost of this more pre-determined machine, as a creature who, naturally, will not pay any mind to what wall he is breaking, 4th or otherwise. The moment during his introduction when Nevermore looks right at the lens, visibly startled as this hulking 35mm apparatus has just lunged forward in order to pull off a tracking shot, recalls a moment in Duelle when the late Hermine Karagheuz jolts briefly out of the action and her character, as she is suddenly aware that scene travelling and transcending pianist Jean Wiener is in the room and has struck his first key. She immediately snaps back into focus in order to play the scene at hand, but still, it is a noticeable and exciting interruption. Nevermore is that rupture made fresh and embodied, a formidable member of Rivette’s “beautiful animals”, as he once called his actors, and just one of many elements in the film that, like in Le Camion, are in conversation across various chasms and limits. Between media, word and the image, concrete reality and imagination, and across the wilderness of time and diverging impulses.