What makes a film dreamlike? Perhaps it’s the authority of a floating image whose fluidity captures one’s attention for hours, resulting in a state of mind that resembles a trance. Momentarily replacing everyday life, cinema is a collective experience, sacred at its core, able to transport audiences to different psychic or physical spaces. It is for this purpose that the Athens International Film Festival emerged for the first time on September 15th, 1995. Twenty-five years later, it keeps that dream alive by paying tribute to the transformational ability of cinema, not only with its poster’s symbolic butterfly design, but also with a strand titled “A Dream within a Dream”. The section includes 17 films, spanning from the 1950s with Albert Lewin’s Pandora and the Flying Dutchman (1951) to the late 2010s with Bi Gan’s Long Day’s Journey into Night (2018), and its mission is to “celebrate cinema and its ability to help people dream with their eyes wide open,” as the festival’s Art Director Loukas Katsikas stated.

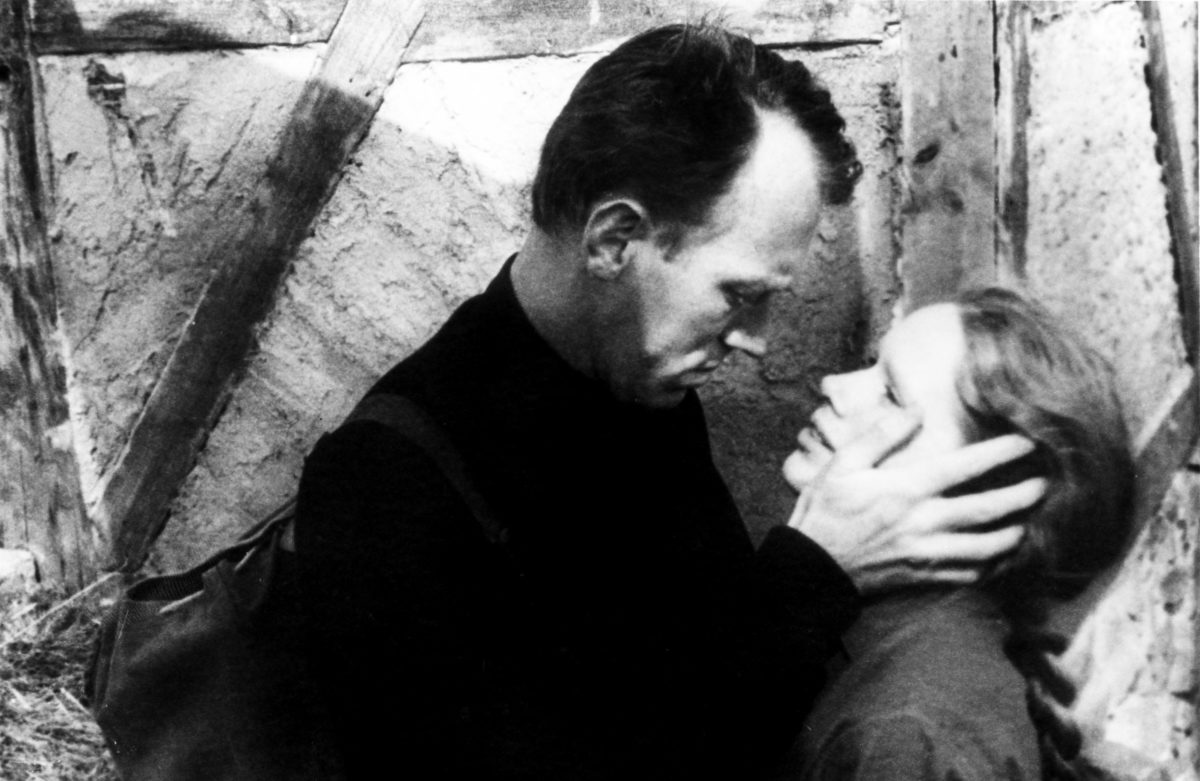

Inspired by the Edgar Alan Poe poem with the same title, the “A Dream within a Dream” strand is a dedication to an aesthetic, far from what we have learned to call real, that blurs the boundaries of the reality/illusion binary. To dream, after all, means to allow oneself a moment of liminality; an entry to another realm of lawlessness that can both enchant and terrify. The festival offers a spot to this in-between space with Ingmar Bergman’s Hour of the Wolf (1968). It comes as no surprise that the strand includes a film by Bergman; he regularly played with themes related to psychoanalysis and Sigmund Freud’s The Interpretation of Dreams (1899). Even if Wild Strawberries (1957)—and more specifically its dream sequence—is a paradigmatic example of this fascination, Hour of the Wolf, and its surreal approach to reality, seems more befitting. Almost naked in its lack of color, not only due to Bergman’s expressionist minimal style but also due to the sense of vulnerability it exudes, it never misses a chance to provoke. Unapologetically refusing to pick a side between the real and the imaginary, which was the unifying project behind the films he made in the 1960s, Bergman produces a nightmare that manifests itself on screen as a delirium with terrifying monsters and stories that are ostensibly fabricated by the tormented mind of the artist Johan Borg (Max von Sydow). Secluded on the island of Baltrum, both Johan and his pregnant wife Alma (Liv Ullmann) are haunted by his visions whose reality can neither be confirmed nor denied.

Following Persona (1966)—although its initial manuscript, titled The Cannibals, preceded it—Hour of the Wolf is considered by some a decline in the director’s artistry. Arguments vary from the film’s extreme vagueness, to Bergman’s overly close association with Johan, who is generally perceived as the director’s alter-ego. This view might be corroborated by the disclaimer in the beginning that the film is a work of fiction based on Johan’s diary, and the subsequent fuss of a filming crew getting ready to shoot a scene—only heard over the opening credits, not seen; it’s an open outing of artificiality read by many as a confession of an attempt to understand an artist’s—i.e. Bergman’s own—turmoil. This interpretation, however, discounts Hour of the Wolf’s place in Bergman’s oeuvre, near the end of his modernist phase, which would culminate in The Rite the following year. The inclusion of the film crew and Liv Ullman directly addressing the camera in the film’s first images, foremost signal the blurring of fact and fiction, reality and illusion. Nevertheless, the director’s proclivity in finding personal answers through filmmaking is no surprise by that point, as most of his projects were explorations of his own fears and anxieties: his struggle with his faith and by extension his relationship with his father who was a priest, his fear of mortality, communication in marriage, mental health and the artist. In fact, both the uncertainty and the semi-autobiographical nature of the film mold it into a successful project of radical truth. Bergman himself has stated that he’s “not trying to make it real, [he’s] trying to make it alive,” and in making it disorienting and deficient in any fundamental concrete message, but full of terror and despair, he is making it alive.

Hour of the Wolf, after all, is also a horror story; a depiction of the artistic impulse to create, and the heavy burden of self-doubt and self-loathing that at times accompany it. Trapped within the confines of the island, Johan is gradually losing grip of his sanity. Notably, Bergman had explored the theme of mental health/instability and isolation before by using the remoteness of the island of Fårö as a vehicle to reflect a character’s deteriorating mental state, with Karin (Harriet Andersson) in Through a Glass Darkly (1961) and with Alma (Bibi Andersson) and Elisabet Vogler (Liv Ullmann) in Persona. Though these films converge in a plethora of points, Hour of the Wolf takes it a step further with its closer association with the horror genre, and specifically with folk horror. Nighttime is no longer simply the hours spent with absence of sunlight; charged with the superstition of a Swedish folklore legend, the night becomes the realm of supernatural forces that lead Johan to experience sleeplessness. The insomniac spells he’s suffering from are a clear symptom of cabin fever, a disturbing claustrophobic irritability experienced due to the confinement marked by the spatial limits of the island. Johan’s inner demons are manifested symbolically in the insufferable, suffocating presence of darkness.

Essential in Bergman’s expressive minimalism of this period, are his extensive use of expressionistically lit and dramatically acted close-ups, as well as the stripping away of independent expressionistic qualities of decor and landscape, presenting only empty spaces filled with tension and drama and austere landscapes that are unchanging reflections of his characters’ inner turmoil. This becomes evident even from the very first night spent in Johan and Alma’s house. Before the break of dawn, Johan counts down a minute with his watch. By seating Alma and Johan at the table with a lamp that illuminates her while leaving Johan in the shadows, yet occupying the plane closest to the camera, the ticking sound of the clock slowing down the passage of time and emphasizing the endless darkness, Bergman and cinematographer Sven Nykvist immerse the audience in the film’s infinite abyss. Placing Ullman at the epicenter, her face giving way to her sorrow and unease, taking long and slow breaths, until the moment she doesn’t blink and doesn’t breathe, accentuates her relief when the minute has finally come full circle. Just a few minutes in, and the unsettling mood of the mise-en-scène has dominated both characters and spectators.

A very similarly staged scene not much later in the film acts as a counterweight to this nightmarish tableau bordering on the dreamlike and illusory. During the daytime, Alma and Johan are again sitting at the table, with Johan once again in the foreground and Alma more to the back but centrally framed. In this scene, she desperately tries to maintain a sense of normalcy, by trying to discuss the family budget—which also involves a rare mention of the mainland—with a clearly preoccupied and thus unresponsive Johan. As emphasized by Alma’s placement in these scenes, Johan is not the narrator of his own story. The film opens with Alma directly addressing the camera, and in fact the director of a film that may or may not be Hour of the Wolf. She starts to tell the story, recounting how she and Johan arrived on the island, a scene which is subsequently enacted on screen. Alma is the narrator, and only cedes this role to Johan—and even then only in a secondary manner—when she narrates how she found and read from his diary. We first hear Johan’s diary entries in voice-over, only to then also see them enacted, aligning the film for the first time with Johan’s point of view. What we have here is already the fourth possible layer of fiction: there’s the film we’re watching; the film being made as evidenced in the opening; Alma’s narration of the events we’re seeing; and finally, the visualization of Johan’s diary.

This aspect of mise-en-abyme also finds its way into the more outspokenly nightmarish parts of the film. Inspired by Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart’s The Magic Flute (1791), in which Prince Tamino is recruited to save Pamina with the help of a birdman named Papageno and is rendered a hero by vanquishing the Queen of Night, Hour of the Wolf frequently references the opera, whose theatricality amplifies the protagonist’s unrest. It begins as a detail with the emergence of Papageno in one of Johan’s sketches. In his inability to understand whether the man’s beak is real or a mask, Bergman hints at Johan’s mental deterioration. Following that, after a dinner inside a gothic castle whose inhabitants are morally depraved aristocrats, comes the puppet show the archivist Lindhorst (Georg Rydeberg) performs; a moment of hopelessness, mirroring Johan’s anguish, as the puppet Tamino, hands in air, asks in exasperation when the night will come to an end. It’s not about the puppet show per se, however, but about the facial expressions Bergman captures with his expressionistic use of close-up shots. Starting with Alma, who reluctantly faces the miniature performance with sad eyes, then slowly tracing the upper-class guests, whose emotions range from exhilaration and fascination to admiration, this array of faces culminates in Johan. With closed eyes and a droopy mouth, he is paralyzed by emotional pain, and desperately waits for it to be over.

For the first half-hour of the film, Bergman mostly alternates between medium shots, wide shots and a few pans. So, when the film cuts to the castle’s exterior with what appears to be a point of view shot, the viewer is taken aback. This change in style signals a change in Alma’s point of view, to a more direct experience of her and Johan’s surroundings. We’re looking through their combined eyes, seeing the new characters walk up to the screen to introduce themselves, addressing Alma and Johan by looking only ever so slightly to either side of the camera. In this first castle sequence, Alma and Johan are almost always shown in the same shot, even if sometimes only through camera movement. This is the first step in the shift from Alma’s point of view to that of Johan. Throughout the sequence, the uneasiness conjured up by the point of view shot is enhanced, most pointedly during the dinner scene. First, the camera circles around the table creating a nauseating sensation due to its fast speed. The room stops spinning, but then the camera pans from person to person in an uncharacteristically quick pace for Bergman’s standards. Voices overlapping and faces interchanging create a claustrophobic atmosphere full of disorientation. Subtly but undoubtedly Bergman is hinting that Johan is spiraling out of control, with Alma left bewildered and pushed to the sidelines. The dinner party is a turning point.

Past the point of no return, Johan and Alma run through a forest, whose mystifying atmosphere not only points back to paganism and the occult but also enhances the night’s symbolic association to Johan’s mental instability and Alma’s growing sense of impotency. Exasperated, Alma pleadingly exclaims to Johan: “They want to separate us. They want you for themselves. As long as I’m with you, it will be more difficult.” Again, Bergman hints to a shift in perspective. Subsequently the film’s title reemerges on screen; hereby, the film itself, outside of its diegesis, signifies the rise of a threshold, just before we are transported to their home. The hour of the wolf is upon them, and the room, now almost completely dark, is briefly lighted every time Johan strikes a match. Non-diegetic music is heard for the very first time. The sound of burning matches agitates Alma who, undoubtedly terrified of her husband’s delusional behavior, is ostensibly still the viewer’s main link. Johan, then, recounts a horrifying memory from his childhood in a tell-don’t-show manner reminiscent of a similar scene in Persona, and proceeds with another story that the audience is forced to witness in the form of a flashback. Another mise-en-abyme, aligning the film firmly with Johan’s point of view. What ensues is a tale of Johan and a boy, possibly his son, fishing in broad daylight. Playing out as a silent-film-like sequence accompanied by Lars Johan Werle’s eerie soundtrack, Johan’s narration is a story of filicide; man is indeed the ultimate monster since Johan, deliberately and with extreme violence, murders his son, or at least that is his version of reality. With such a compromised point of view, Johan cannot be trusted, and there’s no one who can attest to that story’s credibility, but that is beside the point. He has been walking the line between sanity and madness, reality and illusion, from the beginning, and at this point the line has been blurred to such an extent that the film becomes an embodiment of a hideous vision.

Regardless if it was a memory or fiction, Bergman moves forward with Johan’s point of view, escalating this hallucinatory experience to the extremes that the hour of the wolf frame allows him. The members of the aristocracy that reveled in Johan’s shame and agony as they continuously brought up Veronica Vogler (Ingrid Thulin), a woman with whom he once had a scandalous affair, return once again to torment him. While before their appearance was merely questionable as Nykvist’s lighting techniques combined with their makeup granted them a pale complexion and hollow-like eyes, now they enter the stage for the second time in an outright grotesque demeanor. Playing games with genre conventions—i.e. the gothic castle with dark corridors that look as if they belong in a German Expressionist film, vampire-like aristocrats, the casual reference of fangs that seems out of place, and the bizarre resemblance of Rydeberg with Bela Lugosi—Bergman builds an ominous universe, echoing Johan’s interiority nearing destruction, where no happy ending could transpire. Motivated to rejoin the aristocrats for another party when Veronica is added to the equation, a bait Johan cannot ignore as it resembles the call of a siren song luring sailors to their doom, he shoots Alma and ventures toward the castle. Taking advantage of the witching hour, Bergman portrays Johan as an artist in the sense of a creator; his art has an incantatory element seeing that the sketches he described in the beginning gave life to his worst anxieties. Here, the film passes into a new dimension, in which Baron von Merkens (Erland Josephson) walks on the ceiling, and an old woman (Naima Wifstrand) winds up removing her face as a direct consequence of taking off her hat and then promptly uses her eyeball as an ice cube.

The Magic Flute resurfaces as Lindhorst prepares Johan for his meeting with Veronica, black eyeliner and all. Johan is accompanied by flying ravens both in his entrance and his exit, implying he is the impersonation of Papageno. Veronica, in this case a stand-in for Pamina, is a corpse who is abruptly revived by Johan’s touch. Even if Johan supposedly saves Veronica, he doesn’t conquer the Queen of Night; he is defeated with a naked, cackling woman in his arms, filled with horror and shame, while Lindhorst and the rest are staring down at him. Lurking in the shadows and behind walls, they are the monsters hiding in plain sight; they gaze upon the chaos and dismay they created with extreme pleasure, or at least that is what Johan sees. Defeated, he asks, “The mirror has been shattered. But what do the shards reflect?” Hour of the Wolf ‘s pendulum then abruptly seems to swing back to reality, with Alma once again addressing the camera/director. We’re back to her point of view, when she recounts that final night with Johan, corroborating everything that happened up to his returning to the castle. In Alma’s version, she followed Johan into labyrinthine woods, taking the place of the gothic castle. What she claims to have witnessed there further conflates dream and reality, or what happens inside and outside of the characters’ heads, making even her, who started out as a seemingly objective narrator, question which is which.

Hour of the Wolf belongs to a dreamlike world where fantasy and reality are interchangeable. Clearly a project of modernism, the film keeps playing with binaries: reality/illusion, objective/subjective, simple/extravagant, expressionist/minimalist. Though he worked on this theme throughout the 1960s, adding layers of theatricality by playing with point of view and mise-en-abyme, and connecting Hour of the Wolf to The Magic Flute elevate it to a powerful amalgam of ultimate horror. Even if its nightmarish status carries Bergman’s individual fears, at its core, it poses universal questions that are left unanswered. Every scene, in all its absurdity or simplicity, breathes life to a dreadful universe rooted deep within anything that can be defined human; guilt, fear, and creeping uncertainty, but above all else, desire predicated on absence and that is why even if it’s not real per se, Hour of the Wolf is definitely alive.