2. Between Chance and Design: The Puzzling Hong Sang-soo

The Form Will Take You to the Truth

In an interview with Cinema Scope following the release of his highly acclaimed Right Now, Wrong Then (2015) , Hong Sang-soo drew a lovely picture of how the ‘defamiliarization’ in his work takes place:

Imagine this rectangle is real life. I try to come as close as possible to it. How? Using details of my life, things I’ve lived, things I heard from other people I know or I just met. I always mix different sources, and it’s never about myself, but it looks like something that happened, or looks like it’s about me. I want it to be like that. I realized that when I was 23 and was writing a script based on a real story. I felt too tense; I couldn’t move. I needed distance. In the same way, my films are never a parallel line to reality. What I tend to do is to follow an arrow towards reality, avoiding it at the very last second.

His most recent troika of films, On the Beach Alone at Night, Claire’s Camera and The Day After (amazingly all 2017), stories about the aftermath of an affair, about aging, regret, (in)fidelity, jealousy, hypocrisy, mixing business and the personal, breaking up with a longtime partner and the fact that photographing a person changes things (if you include Yourself and Yours from 2016, you could add ‘gossip-mongering’ to the list of self-reflective tropes), Hong has followed that arrow dangerously close to target. When Hong says, “Anything that is important for you may be important for your film,” such opening of a direct channel between art and life sends us back to Godard’s comments (inspired by Sartre) following the release of Une femme mariée (1964): “What an artist creates is inseparable from his life, from life in general.” In an interview with Cahiers from 1962 Godard had similarly noted, “Shooting and not shooting, for me, are not two different lives. Filming should be a part of life and it should be a natural and normal thing.” In Hong’s case, Existentialism came into his work via a number of literary influences that I’ll shortly come back to, the most important of which was André Gide. In Les Faux-monnayeurs/The Counterfeiters (1925), Gide lays out his vision of literary modernism through the theory of the ‘open’ novel expounded by his alter ego, the novelist Edouard X: “For more than a year now that I have been working at it, nothing happens to me that I don’t put into it — everything I see, everything I know, everything that other people’s lives and my own teach me …” Instead of the timid mimetic realism of his predecessors, Edouard decides to rely on pure contingency. When his interlocutor, the Polish psychoanalyst Mme. Sophroniska, perhaps a reader of Proust, inquires whether the ‘plan’ of such a book is made up, he proudly announces, “It’s essentially out of the question for a book of this kind to have a plan. Everything would be falsified if anything were settled beforehand. I wait for reality to dictate to me.”

From On the Occasion of Remembering the Turning Gate (2002) onwards, Hong stopped scripting his films, turning out treatments that dwindled to “a few pages of scattered notes” as his filmography expanded. Since he achieved independence in 2005 with his own small production company Jeonwonsa he basically starts from scratch, coming up with scenes and dialogue every morning before the shoot (à la Godard), drawing inspiration from his own life and that of the assembled performers or from what he finds on the location (for his latest film, The Day After, he started from a small publishing house and its proprietor who liked to come to work very early in the morning). The pleasure derived from relying on such contingency and making your film out of things that are already there, in the world, was memorably described by Noël Burch on the subject of Marcel Duchamp’s ready-mades, another important reference in Hong’s aesthetics: “Any filmmaker, in particular, can attest to the fascination experienced by a creative artist when he contemplates and ‘displays’ objects or materials that he himself has not created and that strike him as being all the more beautiful simply because they are not a product of his talent.”

On the subject of Gide, we should also note the parallel between Gide’s ambiguous relationship to his internal author and alter-ego, Edouard (“Edouard has irritated me more than once — enraged me even,” he has the omniscient narrator say), and Hong’s position towards his autobiographical artist characters. In the knowing Oki’s Movie (2010), struggling film director Nam Jin-goo talks to a student audience about his creative process in one of those cringe comedy moments the director excels at. He tells the students that his process relies on ‘finding a film’: “I just made the film. It wasn’t with any theme in mind. My film is similar to the process of meeting people … I hope my film can be similar in complexity to a living thing.” Mind you, he’s a little drunk when he’s making that speech. In an earlier moment he more soberly councils his thesis student, “Openness and truthfulness alone will get you nowhere,” as well as “sincerity needs its own form” and “form will take you to the truth,” echoing both the New Criticism belief that form is an autonomous vehicle of aesthetic significance and your typical Hollywood screenwriting manual (“Turning points! Two turning points!” Nam rages, misquoting McKee). Which position is Hong parodying here? In On the Beach at Night Alone, the director character replies to the accusation that “personal stories are boring” by stating, “It’s how you make them that’s important.” “And how are you going to make it?” his jilted lover Young-hee asks. “Just as the thought comes to me. Not to set anything in advance.”

Edouard might want to make his novel out of reality, he also dreams of creating a literary work “which should be at the same time as true and as far from reality, as particular and at the same time as general, as human and as fictitious as Athalie, or Tartuffe or Cinna.” But this inevitably involves some kind of a plan — a causal connection between actions, an ordered deployment of meanings and a controlling of affective response — even if the plan or form organically grows out of the material. In his Journals, Gide repeatedly expresses admiration for the French classicists — Corneille, Racine — and notes that even for a modern writer the rules are not there merely to be broken: “In general, insubordination with regard to the rules comes from an unintelligent subordination to realism, from a misunderstanding of the ends of art, from that specious insinuation of empiricism which aims, through a scandalous generalization, to scoff at art by attacking it only where it has become artifice, and to label as factitious all supernatural beauty.” What Edouard is after in his wanting to reconcile disparate, seemingly contradictory elements of everyday contingency and neoclassical idealism, refers back to the age-old philosophical problem of the relationship between the particular and the universal, and, in particular, to Nietzsche’s aesthetic observation that art cannot arise from Dionysian frenzy alone but requires the discipline of Apollonian form.

Edouard’s project is also not so different from Cézanne’s attempt to reconcile classical art with the conflicting data of feeling and perception. Hong has repeatedly expressed his admiration for Cézanne, for the ‘deep’ phenomenological-ontological realism, minimal and elemental, that constitutes the search after truth, for that which is hidden in ordinary, habituated perception. Mallarmé — another probable source — defined modern painting precisely as the “search after truth” of an art that has forgotten “all acquired secrets of manipulation” and possesses the ability to “see nature and reproduce her, such as she appears to just and pure eyes” (at the same time, even in Un Coup de Dés Mallarmé wanted to express his respect for “ancient technique”). Mallarmé’s incentive that “the eye should forget all it has seen, and learn anew from the lesson before it…that which it looks upon as if for the first time,” closely follows Flaubert’s belief that the most important aspect of writing is to learn to see with your own eyes, a credo echoed both by the Rossellinian filmmaker Koo in Like You Know It All (2009), who tells a student audience, “I want to see everything with a fresh eye, without preconceived idea, find something new in appreciating each moment,” and by General Lee Soon-Shin in a hilarious dream sequence in Hahaha (2010): “Don’t see with the thoughts of others. Believe in your own eyes.” But then Flaubert (who also gave his name to the hotel in Trouville where the characters make out in Night and Day (2008)), although still nominally a realist, proved the beginning of modernist aestheticism, just as Cézanne generated Cubism.

There are two common ways to view Hong Sang-soo: as a Apollonian modernist-formalist in thrall to composition, structure and serialism; and as a Dionysian postmodernist fascinated by bodies, multiplicity, chance, indeterminacy and formlessness. The latter position can be detected in Andrew Tracy’s suggestion of formal “exhaustion” in his Cinema Scope review of Oki’s Movie:

Repetition with variations, that time-tested template for artistic creation, is still very much the mode these days, but with a heightened self-consciousness as to the act of repetition — and, perhaps, an intimation of its potential sterility.

The distrust of classical narrative evidenced by many of the best contemporary filmmakers corresponds with their efforts to make their films rhyme, resonate with, or bounce off other spheres outside the film’s narrative universe, whether through multi-part works, reflexive meta-cinematics, or the Herzogian gambit of making the fiction (insofar as it is a photographic record of people performing certain actions) essentially a documentary of its own making.

Those “spheres outside the film’s narrative universe,” recall the traditional allegations lodged at modernism — formalist, autonomous and self-referential and therefore closed off from life, sterile — while the reference to Herzog points to an openness to reality (and ‘the body’) already present in Gide (Herzog’s notion of “ecstatic truth,” a poetic truth established through stylization, on the other hand, more or less corresponds to Edouard’s idea of aesthetic truth). For now, I want to draw another comparison, to an ontological realist less affected by the postmodernist nostalgia for ‘real presence,’ who moreover fully embraces the artifices of art and composition. I’m talking, of course, of Eric Rohmer.

Like Hong, Rohmer was an admirer of Lumière, whose famous quote that his films are “meteorological” fits with the importance of setting and seasonal atmosphere in Hong, whose films are a feast of umbrellas: the snow in the final scene of Right Now, Wrong Then can be considered as fortunately contingent an event as the famous snowstorm in Clermont-Ferrand in Ma nuit chez Maud (1969). (“Some people think Rohmer is in league with the devil,” cinematographer Nestor Almendros observed on his working experience on Maud. “Months before, he had scheduled the exact date for shooting the scene where it snows; that day, right on time, it snowed, and the snow lasted all day long, not just a few minutes.”) In many ways Hong is as ‘touristy’ a filmmaker as Rohmer, a maker of travelogues that alternate between the city of Seoul and picturesque islets and coastal towns or resorts.

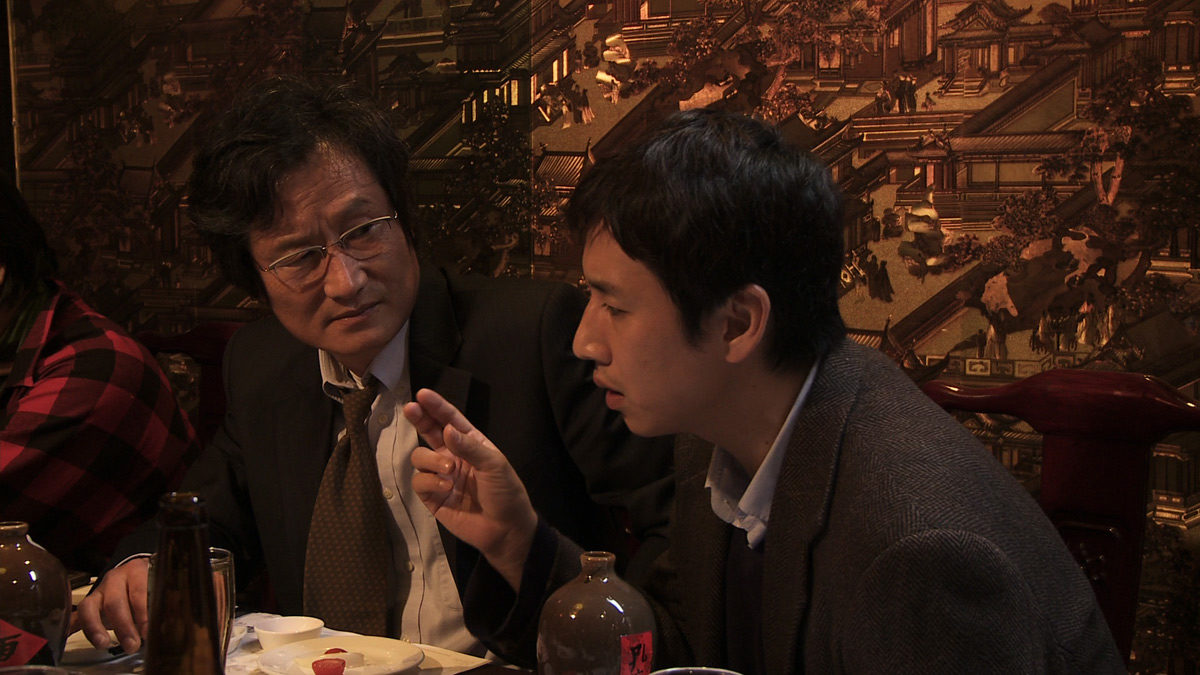

Like this most Rossellinian/Renoirian of the nouvelle vague cineastes, Hong likes the idea of quickly set-up production that, despite the beauty of the photography, gives the impression of having been ‘sketched’ rather than fully worked out (on his second most recent film, Claire’s Camera, he shot for 9 days, finishing the final edit a day after the end of the shoot), leaving things to chance and remaining open to the sudden intrusion of natural contingencies into the totally artificial world of the work of art. Hong’s films, like Rohmer’s, are punctuated by ‘documentary’ moments: the encounter with Zuppi the pony on the beach or the squid tentacle sticking to the aquarium in The Power of Kangwon Province (1998); the discussion with Korean painters working in Paris in Night and Day that has a vérité quality comparable to Gaspard and Margot’s interview with an old sailor in Conte d’été (1996); the frequent cutaway shots to families and couples enjoying an afternoon in the park that recall the walkers in the Buttes-Chaumont section of La femme de l’aviateur (1981). Although, like Rohmer, Hong isn’t really drawn to non-professionals and needs actors that can speak his lines correctly (“It happens that my line, which seems natural, is actually artificial. It has to be very precise, and amateurs cannot adapt to it. That’s why I work with professionals: they can be very precise and do what I want them to do” — a quote from Hong that might as well have come from Rohmer), he likes to keep ‘accidents’ when they ring true: in Turning Gate an actress can be seen cracking up in the background of the scene with Gyeong-soo and Seon-young’s overbearing parents, while in Claire’s Camera Huppert and Kim are almost run over on a Cannes crossing, all takes Hong decided to use, just as Rohmer kept the one of Arielle Dombasle putting her hand in front of her mouth to indicate she wants to interrupt the filming in Pauline à la plage (1983). Rohmer’s idea of the auteur film as ‘amateur’ film is flagged by the handwritten title cards and diaristic indications of date and time that Hong seems to have borrowed from Le genou de Claire (1970), Le rayon vert (1986) or Les rendez-vous de Paris (1995). Both their styles are strikingly ‘sparse,’ opting in Hong’s case for long takes with natural light and mostly static framings (like Rohmer, Hong often withholds a reverse angle during lengthy conversation scenes) that seem to hark back to the earliest days of cinema and its ambition to capture pure reality. Hong’s favorite shot is that old staple: the two-shot of a man and a woman sitting at a table talking, either profiled or at a more oblique angle (on the cinematic qualities of that sparse option see ‘Where did the two-shot go? Here.’ on David Bordwell’s blog). No dolly or crane in sight here, with movement limited to simple pans and reframings that frequently activate offscreen space, or to the optical effect of shifting lenses in the zooms he starts to use from Tale of Cinema (2005) onwards. Hong’s favorite camera movement is to tilt or pan or zoom away from a character to a tree, a move familiar from Hou Hsiao-hsien that can be given the standard Confucian interpretation as signifying that nature is impervious to human affairs (the Buddha itself seems to connote that meaning in the unassuming opening insert of a Buddha statue on a roof adjacent to the house of Hee-jeong and her mother in Right Now, Wrong Then) but that can also put us in mind of the Bressonian maxim that the actor and the tree belong to different worlds.

In casting, Hong also stays as close as possible to real life: “The person interests me above all, that’s the core: I see them as persons, and have no opinion about their work as actors. I often don’t even know what films they have done before. Based on this impression, sometimes I remember something that happened to me a long time ago, some situation, some dilemma or lost memory.” Again as in Rohmer, the line between character and performer is constantly erased, or, as Rohmer puts it, “There is no artistic transposition from actor to character” (actors lending their personality to the film also works to keep the autobiographical narrative at a distance). This is Rohmer’s ‘research’ side: having conversations with the actors beforehand and drawing from them the material for scenes that seem completely improvised (although there isn’t a lot of improvisation in his films, Le rayon vert, a completely improvised film, is one of Hong’s all-time favorites). In all Hong’s films, art is mixed with the personal lives of both director and actors: in both Nobody’s Daughter Haewon (2013) and Right Now, Wrong Then reference is made to a character’s potential/career as a model, which fits with the previous employment of actresses Jung Eun-chae and Kim Min-hee. That the latter’s English is really bad is a joke that recurs in On the Beach at Night Alone and Claire’s Camera.

Ridiculous Men

On the other hand, there’s that deviated arrow, which I want to take as Hong’s theory of defamiliarization. For Hong, ‘ostranenie’ concerns both the phenomenological principle of learning to see again with ‘fresh eyes’ and the device of narrative construction. Construction is where his modernism lies: despite the prominence of contingency — both as a thematic and dramaturgic presence —, form (in this case narrative repetition, variation, contrast) gives coherence to the presence of mundane details in Hong’s films. The fact that he starts from only the briefest of outlines or “a little bit of story,” has led his plots to have been generally dismissed as episodic and inconsequential, as a “loose accumulation of scenes.” The fact that his films have also been called ‘plotless,’ once more illustrates the confusion between ‘story’ (a string of events in a time sequence) and ‘plot’ (the arrangement of these events through various devices of causality and temporality). While it is true that Hong’s stories are minimal and situational, focused on routine actions and behavior (eating, drinking, sleeping, walking, making love), his plotting — the actual presentation and arrangement of the story actions — is complex, relying on scrambled or uncertain chronology, unmarked flashbacks or dream sequences, block construction, narrational strategies and procedures of ellipsis, delayed or absent exposition and modes of viewpoint (and voice-over narration).

There are three basic ‘situations’ in Hong’s cinema of the script-less period — all variations on the two Ur-storylines of a stranger coming to town, or a character going on a journey: a commercially unsuccessful (though sometimes critically lauded) filmmaker, actor, writer or painter, who in some cases has studied or worked abroad and often does double duty as a teacher, goes traveling to a picturesque location, by invitation from a friend, a film festival or a university; he wants to get his mind off a recent professional or amorous disappointment and, mostly after some heavy drinking in a bar, restaurant or hotel room, falls in love with a new woman, in many cases the partner or spouse of a friend or colleague. In the alternative scenario the protagonist is on the verge of leaving abroad or has already returned from an overseas stay and we gauge the difference between his/her past or present situation. The third scenario involves teacher-student relationships in which a married man with a family is suffering from a midlife crisis and has to make a choice, and a student-rival is involved. In the last three films, the latter scenario has evolved into the aftermath of a relationship. These storylines (together with key motifs like drinking and clumsy lovemaking) constitute the deep structure of Hong’s cinema, that gets transformed, varied and repeated in different films. In some cases a relationship is established between immediately succeeding films: the love triangle between a former student, her married professor and former student boyfriend in the short Lost in the Mountains (2009) seems a dry-run for Oki’s Movie. But most of the time Hong is playing according to a much broader outline, displaying an obsessive reiteration of favored structures and motifs: strong relationships exist between movies that were made years apart: Turning Gate and Like You Know It All are both two-part stories in which a Seoul film professional visits a friend in the country and ends up seducing the friend’s lover/wife who’s a ballet dancer, a trope briefly introduced in The Day a Pig Fell Into the Well (1996). Hahaha and Nobody’s Daughter Haewon feature a love relationship between a depressed married professor and his student and a divorced mother and adult child saying goodbye before either the one or the other leaves for Canada, where an aunt/brother is already living (in both cases it’s the one staying who feels sad, bursts out in tears and has to be comforted). The Day He Arrives (2011) and Hill of Freedom (2014) are two variations on the protagonist coming to town to see an old friend/lover that cannot be found. In both a young woman is sad because she has lost her dog. Sometimes a fetishistic detail reappears: Tale of Cinema and Night and Day both feature a shot of feet sticking out of a bed that’s recognizably Buñuelian (as are the shots of insects in Like You Know It All). Most obviously the titles of Hong’s films show an Ozu-like consistency: Woman on the Beach (2006) and On the Beach at Night Alone; The Day After, The Day He Arrives, and The Day a Pig Fell Into the Well; the meta-films Oki’s Movie and Tale of Cinema, and the mirroring pair of Yourself and Yours and Right Now, Wrong Then (although these particular reflections possibly arose during translation).

The repetition of certain motifs, scenes or themes is also often tied to the presence of a specific performer. The presence of Isabelle Huppert in In Another Country (2012) introduces a new perspective on the ‘international’ theme, mainly the difficulty of communication between East and West that mirrors that between the sexes, which will be developed in Claire’s Camera and On the Beach at Night Alone. Huppert’s partner in In Another Country, Yoo Joon-sang, unforgettable as the goofy love-struck lifeguard, plays a depressed man doubting between his wife and his girlfriend in Hahaha. In Hahaha and The Day He Arrives, Yoo, a multi-instrumentalist and performer in real life, plays the piano beautifully and his friend says it’s embarrassing.

In the first two of his three films with Hong (Turning Gate, Tale of Cinema, Hahaha), Kim Sang-kyung is extremely uncomfortable around families with small children, over-compliments his friend’s wife on her cooking and is insensitive to the children’s discomfort (he hardly flinches when a child’s finger gets stuck in stuck in a car door in Turning Gate and lights up in the car with a sick kid in Tale of Cinema). In Turning Gate and Hahaha he follows a woman to her house (“You’re like snake, sneaking around and following people,” she says, referencing the legend behind the Turning Gate). Most importantly, in both Turning Gate and Tale of Cinema he can’t get an erection when drunk and proposes suicide instead: “I’d like to die, end with a flourish — let’s die clean, without making love”/“What if we died together? I want to die pure and innocent, without making love.”

Kim Tae-woo plays the schlemiel whose girlfriend falls for his friend in Woman Is the Future of Man (2004) and Woman on the Beach, and who suffers humiliation when his own attempts at seduction go belly-up in Like You Know It All. Lee Sun-kyun, finally, is paired with Jung Yu-mi in Oki’s Movie and Our Sunhi (2013); in both films, and in Nobody’s Daughter Haewon, he’s a filmmaker/academic who’s madly in love with a former student/classmate. The most recent films have been built around players with contradictory qualities: blusterous, somewhat aggressive yet goofy and world-weary Kwon Hae-hyo, and most of all sensitive but resolved Kim Min-hee who turns from fragility (or “detached latency” according to Cahiers’ Vincent Malausa) to disdain in a soft heartbeat.

To get a sense of Hong’s approach to plot construction, I want to take a close look at his first three scripted films. These films were highly ‘literary’ and provided the template for the ‘looser’ films to follow, featuring chapter titles and divisions, play with point of view and character narrators. Hong’s literary inspiration is well-known and has increasingly come to the fore in scenes set in or around libraries, bookshops or publishing houses (Claire and director So from Claire’s Camera must be the only visitors in the history of the Cannes film festival to ever end up at the local library!), but has largely been neglected, probably because his characters are most often filmmakers or painters. But there have been writer characters (actual writers, not script writers) in The Day a Pig Fell Into the Well, Lost in the Mountains, Hahaha, In Another Country, The Day After and Claire’s Camera. Three films draw their titles from literature: The Day a Pig Fell Into the Well and In Another Country were inspired by short stories by John Cheever and Hemingway, while Woman Is the Future of Man and On the Beach at Night Alone reference poems by Louis Aragon and Walt Whitman.

Hong’s films are larded with references to Kafka (in Yourself and Yours, Min-jung’s double can be seen reading ‘The Metamorphosis,’ while Kafka’s is the most visible author’s name in the composer’s bookcase in On the Beach), most notably in Like You Know It All, in which filmmaker Koo is blamed both for seducing his friend’s wife (which he only dreamt?) and for the film festival programmer’s rape by director Kim. Kafka’s main influence can probably be detected in the lack of character background information. The cypher-like nature of many of Hong’s protagonists also derives from Hemingway, as does the alcoholism, self-loathing, casual misogyny and alienation, but also the social comedy and the pithy, laconic, ’behaviorist’ style full of hard-edged ellipses. (I should note here that the sexual frustration that is typical of most of Hong’s males comes from Hemingway, but also has another source, revealed by the title of his first film: the ‘bachelors’ in Duchamp’s The Large Glass are forever separated from the bride, who remains forever in the process of being stripped bare, without any actual release in sight. The voyeuristic unease experienced by viewers confronted with the explicit and lengthy sex scenes of Hong’s early films is also on a par with Duchamp’s games with spectacular eroticism.) The main storylines of visitors coming to countryside from the city, bringing romance into the lives of the inhabitants with mixed results, is typical of Chekhov (Hemingway’s main inspiration for his ‘Iceberg’ theory of literary prose) — as is the nostalgia for the halcyon days and the deep sense of regret and missed opportunities (Chekhov’s ‘About Love’ is the story read by the director in On the Beach at Night Alone). The loneliness and bitter discontent of Chekhov’s protagonists, like the taste for drink, we also find in Dostoevsky, whose fabulous short story ‘The Meek One’ (1876) informs Hong’s myopic characters, incarcerated in their own private worlds, obsessed with death and the ‘idealized’ purity of the women they want to bed: in The Day a Pig Fell Into the Well, Min-su tells Min-jae, “You are a clean woman — what will happen if purity fails to work?” while in Woman Is the Future of Man Hyeon-gon tries to restore the raped Seon-hwa’s purity by bedding her; most recently, in Claire’s Camera, director So is appalled by the thick make-up and hot pants Man-hee wears to a Cannes cocktail party. The scene in Pig in which a writer gets snubbed by old school friends during a reunion, repeated in Tale of Cinema and Oki’s Movie, is a close facsimile of the Underground Man’s humiliation at the going away dinner party with old school friends in Notes from the Underground (1864), in a chapter bearing the Hong-like title ‘Apropos of the Wet Snow.’ Hong might have gotten to Dostoevsky through Bresson or Gide (who gave a series of lectures and wrote a book on the Russian), but the (talk of) suicide attempts in Night and Day, Like You Know It All, and Tale of Cinema, and the fact that Hong tried to commit suicide in his last year of high-school, shows that there’s a close personal identification with Dostoevsky’s ‘ridiculous man’ and that the Russian holds pride of place in Hong’s pantheon of Existentialist writers.

The critic Tony Rayns has chided ‘lazy critics’ for sticking to the Hong-Rohmer comparison, seeing nothing in common between them other than that they are both preoccupied with “the vagaries of the heterosexual libido.” Much more specifically, however, in Rohmer’s ‘Moral Tales’ at least, the preoccupation is with the indiscretions and inconstancy of married men or almost-married men chasing after young girls, a scenario familiar from any Hong film. The hypocrisy of catholic seducer Jean-Louis in Maud is reflected by married Sung-nam in Night and Day, who decides after reading the bible that he should ‘overcome temptation’ and not sleep with married Min-seon. The film’s ending, in which Sung-nam returns to his wife, is also very similar to that of L’amour l’après-midi (1972), and is more cynically rehearsed in The Day After (only in Haewon and Hahaha do characters actually leave their wife and child for their mistress). Like Jean-Louis and Frédéric, Hong’s males frequently deny their Lotharian tendencies: in Turning Gate, actor Gyeong-soo responds in the negative to his writer friend’s question whether he sees himself as a seducer, while at the same time he’s ogling a young girl on the bridge; in Like You Know It All, Koo’s ex-business partner senses trouble when running into his old friend: “You want me to shout it out? Hide your daughters, he’s a skirt-chaser!” Like Rohmer’s seducers, Hong’s narcissistic men are constantly in their own head, never paying attention to the people around them (in Tale of Cinema, Dong-soo failed to notice that one of his friends has a limp): they constantly forget about past girlfriends, in Turning Gate and Night and Day, but most radically in the final act of The Day After. And we’re in theirs: the voice-over, although Bressonian in tone, is also distinctive of the highly literary ‘Moral Tales’, denoting a Jamesian ‘central consciousness’ whose reflections and emotions color the presentation of the storyline and the other characters.

What a Coincidence!

The Day a Pig Fell Into the Well, Hong’s first film and his first experiment with block construction, started as a kind of corps exquis experiment, for which he assigned four students to write a short script based on a day in the life of a character of their choice. He then took these four scripts and wove them together, with a separate chapter for each of the film’s characters. The four parts are presented sequentially, corresponding to the point of view of four people involved in different romantic triangles: failed novelist Hyo-seop, his sweet caring girlfriend Min-jae, an aspiring writer ticket-girl at a local cinema who does voice-over for erotic manga on the side, his stylish and self-possessed married lover, Bo-kyung, with whom he’s actually in love, and her estranged bacillophobic businessman husband, Dong-woo. Thrown into an already volatile mix is Min-soo, an ex-con who works at Min-jae’s theatre, who will prove the instrument of the film’s shocking finale. Because he headlines the first chapter and most closely resembles Hong’s typically narcissistic male anti-hero prone to drink, our inclination would be to take Hyo-seop to be the story’s protagonist, the center of the circle. In fact, it’s Bo-kyung who’s allotted most of the screen-time and has the most distinctive ‘arc.’ She’s also the only character whose path crosses with that of the other three. Still, the best way to characterize the film is as a multiple-protagonist or ‘thread narrative’ of a type encountered in the realist nineteenth-century novel (War and Peace is arguably the most ambitious instance of the thread or ‘network’ narrative, but the three brothers of Karamazov certainly apply). As both narratologists and screenwriting gurus have argued, multiple narratives typically create a strong sense of suspense, as audiences stay enthralled to find out the connections between characters that are slowly made apparent. In Pig, all the character’s individual choices and trajectories — the writer’s brutal rejection of his ‘nice’ girlfriend, the husband (possibly) contracting gonorrhea from a prostitute, the wife deciding to run off with the writer, the ‘nice’ girlfriend sleeping with an ex-con co-worker — directly affect the other points of the circle. The different threads converge in a final chapter attached to Bo-kyung’s point of view, in which she fruitlessly searches for the writer and finds out about the ‘ultimately determining instance.’

The Day a Pig Fell into the Well shares both its violent dénouement and rumination on chance and contingency with Gide’s The Counterfeiters. If you take away the self-conscious strategies of mise-en-abyme, you could characterize The Counterfeiters as a Tolstoyan family saga in miniature with 28 major characters whose relationships as familiars (friends, family) or strangers is interwoven according to the principle of n-degrees of separation. However, Gide criticized Tolstoy for essentially painting panoramas in which each event comes into the foreground in succession: “Their lives never mingle, as in Dickens and Dostoyevsky.” From the latter, Gide adopted the principle that the novel as a form is first and foremost free and chaotic. The Russian literary theorist Mikhail Bakhtin famously commented on Dostoevsky’s “polyphonic” novels, noting that their world “may seem a chaos, and the construction of his novels some sort of conglomerate of disparate materials and incompatible principles for shaping them.” In a passage that is highly similar to Gide’s criticism of Tolstoy, Bakhtin writes that where “Goethe stretches out events in an evolving (temporal) sequence, Dostoevsky attempted to perceive the very stages themselves in their (spatial) simultaneity, juxtaposing and counterposing them dramatically.”

The Counterfeiters was composed according to a tight plan, an almost mathematical structure that is explicitly likened to fugue composition: there are three parts, of which the middle section (the only one that doesn’t take place in Paris) serves as an interlude; the eighteen chapters and 220 pages of the first part exactly parallel the eighteen chapters and 225 pages of the third part. The different chapters alternate between omniscient narration with an over-arching point of view in the manner of Fielding (“We should have nothing to deplore of all that happened later if only Edouard’s and Olivier’s joy at meeting had been more demonstrative”) — the summary chapter titles of which seem also to have inspired a minimalist version in Turning Gate, which features capitula titles like, ‘Gyeong-soo goes to his production company and argues with the director’ — and interior monologue, dialogues, free indirect discourse, letters and journal extracts, a more ‘objective’ narration that dilutes the author’s presence. Besides the different modes of narration there are at least seven ‘focalizers’: Gide attaches us to one character, then another — in chapters with titles like ‘Bernard and Olivier’ or ‘From Bernard to Olivier’ — but also lets their paths and plot-lines intersect and converge (Bernard and Olivier are friends). When Bernard runs away from home after having learnt that he is an illegitimate child, he seeks shelter with Olivier. Olivier’s older brother Vincent has had an affair with a married woman. Vincent breaks off with Laura after he gets her pregnant, falling under the spell of the decadent novelist Passavant, Edouard’s competitor, who introduces him to Lilian Griffith, with whom he begins another affair. Bernard, who accidentally learns that the novel’s central character, the novelist Edouard, Olivier’s uncle, has been in love with Laura since his days as a boarder in the pension run by Laura’s father by reading his diary. He heroically and sentimentally decides to take charge of Laura and becomes Edouard’s secretary, just as Olivier gets reeled in by Passavant. A third family, the La Pérouses, introduce a family reunion plot that will directly lead to the tragic dénouement at the pension, involving members of all families.

The crisscrossing paths and events, achieved mainly through family connections between the Profitendieus and the Moliniers, between mutual friends and acquaintances (creating a social network or ‘web of affinities’), but also by a striking parallelism established between the threads of Bernard and Olivier or the Profitendieus and the La Pérouses, take off from the shared spatial frame of the pension, Gide’s equivalent of Balzac’s Maison Vauquer, the Parisian boarding house in Le Père Goriot (1835). The city itself is of course the prime site of intersecting paths, and in this sense Gide’s novel can be seen to stand, as the Marxist theorist Fredric Jameson has arguedAs an aside, it’s interesting to compare The Day a Pig Fell Into the Well to Edward Yang’s The Terrorizers (1986), the subject of Jameson’s essay, ‘Remapping Taipei,’ in which the point of comparison is precisely The Counterfeiters: both are slow-burning stories about linked destinies and urban alienation and anomie shared by the privileged and underprivileged alike that more or less end in execution-style murder (the synecdoche of the blood-splattered wall and the preference for carefully framed shots with static camera seem to suggest the Bresson of L’Argent (1983), another network tale in which connections are created through the circulating object of the forged banknotes). You could even find in Yang’s career-driven, narcissistic, emotionally retarded doctor figure with marriage problems, about whom it is hard to have any feelings of sympathy, a precursor to what would become the typical Hong protagonist (the compulsive hand washing of this character returns in the germaphobe businessman)., between the classical and modernist panoramic novel, or between the classical closed plot and the providential family reunion plots of the Victorian novels of Dickens, Eliot and the Bröntes, and the spatial multiplicity of the new industrial city where isolated individuals only converge by chance. Whereas in, say, Bleak House (1852-53), the structural backbone revolves around the genealogical mystery connecting Esther to Lady Dedlock, in Mrs. Dalloway (1925) the famous Regent’s park scene depicts unconnected characters from the different plot strands in random spatial contiguity.

Meetings between former lovers or old friends, or even mutual acquaintances provide the starting point for most of Hong’s films. These come about through coincidence, if not in the principal pairing (mostly one friend visiting another who has moved to the country, or one friend/lover hooking up with another after a period spent abroad), then at least in the secondary relations that split off from this pairing (one friend falls for the other’s wife or mistress who then becomes the primary mover of the action). The plot device of old friends meeting again by chance is central to Woman Is the Future of Man, Night and Day and Like you Know It All, and varied with that of the urbanite visiting a friend in the country in Pig, Turning Gate and Like You Know It All. It is in the role played by chance, both in the mise en scène of his films and in the dramaturgy of fortuitous encounters, that Hong most closely resembles Rohmer. Like Rivette in a more explicitly surrealist vein, Rohmer was in thrall to the mysterious connections that make up the everyday, especially when you’re living in the city. Richard Misek’s wonderful video essay, ‘Mapping Rohmer’ (2012, which led to his feature-length film from 2014, Rohmer in Paris) shows how Rohmer’s characters, while tracing actual paths through Paris, keeping geographic continuity, cross paths and “become a part of a larger network of lines.” Night and Day, set in Paris, in which the main character connects with friends and lovers in cafés, coffee shops, restaurants and parks, and through them meets future friends and lovers, is Hong’s film in which he most closely follows this Rohmerian template set by Ma nuit chez Maud. In Maud engineer Jean-Louis, who hardly ever goes out, runs into his philosopher friend Vidal in a bar in Clermont and proposes the probability of them running into each other again within the next two months (in an earlier scene he is seen browsing through a ‘Cours moderne de calcul des probabilités’ in a bookstore). This discussion of mathematical probability leads into a conversation about the philosopher-mathematician Blaise Pascal’s probabilistic reasoning in his famous ‘wager’ that will determine much of the rest of the plot.

The Day He Arrives (2011) — which shares its wintry setting with Rohmer’s Clermont — similarly appears as a rumination on the ‘rencontre par hasard’: the retired filmmaker Seung-jun returns to Seoul to visit a friend and runs into an actress-student of his not once but three times. His friend’s unofficial girlfriend had the same experience, running into three film people during one afternoon in the city, a feat bettered by Seung-jun when he crosses paths with four specimen in one street at the end of the film. Such crazy happenstance naturally leads into discussions on whether they are proof of final randomness or some kind of ‘Design.’ Tellingly, both positions are entertained by the same character: “No need to make up reasons for it. Just take in these marvels of life,” Seung-jun tells his actress friend when she wonders why she keeps running into him, whereas in an earlier scene he had philosophized that, “Random things happen for no reason in our lives. We choose a few and form a line of thought … made by all these dots which we call reason.” The rational explanation is contrasted to the fantastic explanation, extolling the invasion of the everyday by the marvelous. In Woman on the Beach, director Kim lays out the story for his new film, to be titled ‘About Miracles’: a man travels to a foreign beach and stays at a hotel. In his room he plays Mozart. Then he leaves the room and the same music is playing in the lift. He leaves the hotel and on the corner is a clown who’s doing his mime to the exact same music. The man doesn’t think it’s a mere coincidence. He concludes that if he can find the reason why this happened, he can unravel the secret of the world. In Claire’s Camera, Claire becomes acquainted both with Man-hee and the director and producer who fired her. “You met him by chance?” Man-hee incredulously inquires after Claire shows her the picture she took of director So. She finds this “marvelous,” but for Claire it’s just “strange.”

“Strange,” in Claire’s experience, more or less coincides with what Freud called the “uncanny” — a feeling of something being both strange and familiar. As a matter of fact, Freud’s definition of a literary uncanny comes quite close to the kind of ‘defamiliarization’ we find at work in Hong’s films: “It is true that the writer creates a kind of uncertainty in us in the beginning by not letting us know, no doubt purposely, whether he is taking us into the real world or into a purely fantastic one of his own creation.” Freud, of course, was a formative influence on the Surrealist avant-garde, and its belief in ‘objective chance’ as the projection of the subconscious upon everyday reality (a variation on the Romantic idea that the poet can read in nature the turmoil of his own mind). For Breton and Aragon, the streets of Paris were where a chance existence could lead to the disclosure of the marvelous, to new encounters with objects, places and individuals. The presence of Surrealism is flagged in Hong’s filmography by the references to Aragon and Duchamp in the titles of The Virgin Stripped Bare By Her Bachelors and Woman Is the Future of Man (a quote he found, Surrealist style, on a French postcard); in the corps exquis experiment of The Day a Pig Fell Into the Well; in the fetishistic attention to found objects (the gum wrapper on the ice in Virgin, the milk carton in Oki’s Movie); in the magical talents of characters who can fill a restaurant (Turning Gate) or conjure up a white cab (Nobody’s Daughter Haewon) at will; in the eroticism of Soluble Fish, in the (soluble?) fish that jumps from its bowl in Seoul to end up in Kangwon Province; but most of all in the deadpan and ‘black’ humor he derives from Buñuel: some of Hong’s most choice moments are Buñuelian in this sense (how many indelible images of toe sucking can you bring to mind, other than those from L’âge d’or and Virgin Stripped Bare?). From the most recent films: Young-hee carried away on the shoulders of an unidentified man in On the Beach, the same mystery man who will reappear in the film’s second part to enact a Keatonian window-cleaning dance; Man-hee wanting to take a selfie with her boss after getting fired to commemorate the occasion in Claire’s Camera.

Freud’s uncanny is exemplified by the trope of the Doppelgänger, which Hong thematically develops in Turning Gate, Tale of Cinema, Woman on the Beach, Like You Know It All, and most explicitly in The Day He Arrives and Yourself and Yours in which the male’s love interest in the film’s second part is a Hitchcockian dead ringer or spiritual substitute for the love object in part one (mostly played by the same actress). Only in Hahaha does a distinctive doubling occur amongst the male characters, mainly between film director and local poet who are both involved with the same woman: the director starts writing poems like the poet, he was in the airborne forces like the poet, and his mother wants the poet to call her ‘mom’ and gives the apartment the director doesn’t want to the poet, just like she gives the baseball cap her son gave her to the poet (in an exquisite irony, it’s the cap that reminds the woman of the poet and makes her get back in touch with him after dumping the director). Generally, in Hong films people are constantly saying they look like other people, whether it’s Mi-sun and Ji-sook who are told they look alike in Pig, or the cop in the same film who looks like a teacher one of the girls knows, or Hae-won who is told by Jane Birkin in a dream sequence that she looks like Charlotte Gainsbourg.

The Doppelgänger theme of Yourself and Yours has commonly been taken as a variation on Buñuel’s Cet obscur objet du désir (1977), but it’s Le Charme discret de la bourgeoisie (1972) that is the bigger influence, especially on the unmarked nested dream sequences that show up in Pig, Tale of Cinema, Woman on the Beach, Night and Day, Hahaha, In Another country, Nobody’s Daughter Haewon, Yourself and Yours and On the Beach at Night Alone. The first such sequence, in Pig, actually pays silly homage to Dreyer’s Ordet (1955), but by the time of In Another Country we’re very close to Buñuel-Carrière’s embedded dreams in Charme (a dinner at a French colonel’s dining room is in fact a stage set in a theatrical performance, that turns out to have been dreamt by Sénéchal. He wakes up and proceeds to the ‘real’ dinner party where Acosta is insulted by the colonel and shoots him. This also turns out to have been a dream, not dreamt by Sénéchal but by Thévenot, who explains to his wife that, “First I dreamt that Sénéchal dreamt that we went to a theatre …”). In Country’s second story Anne goes to the lighthouse where she is surprised by the lover she is waiting for. They kiss and then she is woken up by a fisherman (in On the Beach, Young-hee also falls asleep at the beach and dreams about her lover). She returns to her holiday cottage and goes to sleep and is woken up by her lover. They go out to look for her lost cell phone then go to a restaurant where the drunken lover makes a scene. This turns out also to have been a dream. The logic is Buñuel’s: First I dreamt that I dreamt that I was surprised at the lighthouse, then I dreamt that we went looking for my cell phone.

Double Helix

Hong’s second film, The Power of Kangwon Province (1998), is another experiment in presenting interlocking lives with the emphasis on comparing the reactions to a painful breakup by the two halves of a romantic couple. The film is divided in two parts, again presented seriatim, in which the male protagonist of the second part, the academic Sang-kwon, turns out to have been the married lover of Ji-sook, one of the young women who go hiking to Mount Kumgang in the film’s first part. We will only get this information quite late in the film, when Sang-kwon and his friend Jae-wan talk about his young lover. As in Pig the narration is restricted to a character’s viewpoint and delays exposition, withholding knowledge and concealing crucial relations or narrative connections. Both go back to Wonsan, the place where they had their first romantic outing. Unbeknownst to each other, they go back at the exact same time, even sharing an inbound train (the girls have standing places only) and going to the same sashimi place (framed differently in each case). The slow revelation of the romantic connection between Ji-sook and Sang-kwon — which Hong expresses diagrammatically as (2-1) + (2-1) = 2 — makes us guess about the relationship of the two halves, especially after the point when the film loops back to the opening scene in the train and has in a sense started over from the same switch-point. Such ‘replay’ of the same scene from a different character perspective is familiar from literary modernism: in Joyce’s Ulysses (1922) the beginning of part 2, ‘The Odyssey’ (focused on Bloom), loops back to the exact same time of the beginning of the first part, ‘Telemachus’ (focused on Stephen). Faulkner similarly connects the Lena-Byron story and the Joe Christmas story in Light in August (1932): in the opening scene Lena arrives in Jefferson on the very day, we will later discover, the murder committed by Joe is discovered. She notices the smoke plumes from the fire at Joanna Burden’s plantation as she rides into town on Saturday morning, a timeframe we reenter once we have found out how and why Joe committed the murder. In his recent book, Reinventing Hollywood (2017), on Hollywood’s appropriation of modernist literary ideas (via a blending with ‘well-made’ conventions, creating a ‘Middlebrow Modernism’), David Bordwell discusses the idea of the ‘replay’ in the context of flashback movies like Citizen Kane (1941) and All About Eve (1950). Our memory of the original — in this case the opening scene — is triggered when we recognize the situation: a man getting beer and dried squid from the cart. In Aspects of the Novel (1927) E.M. Forster already pointed to the importance of memory for following a plot: if we don’t remember we can’t understand.

To complicate things even further, Hong sets the fallout from the couple’s breakup against the backdrop of a local murder case in which Sang-kwon will become involved as a witness. During their hike Ji-sook and her friends cross paths with a young woman and an older man on an iron bridge crossing a stream. They later learn that the woman has fallen off a cliff and was presumably pushed. In the second part — which starts at an earlier point and ends later — we see how Sang-kwon meets the same woman, learns that she is a prostitute and sees how she gets picked up by a shady guy. The narrative’s double point of view thus creates moments of overlapping replay that makes us feel the presence of Ji-sook in the second part of this ‘double journey’ plot in which the protagonists only meet after the trip, during the film’s epilogue. The pleasure of watching the stories occasionally mesh — like when we see Sang-kwon write the message on the wall of Ji-sook’s apartment that she erased in the first part — is part of a bigger pleasure in constituting a precise temporal framework: when exactly after Sang-kwon last saw the girl did Ji-sook and her friends run into her and the shady guy? How close does that put them together? There is also the pathos of the past weighing on the present when it becomes clear Sang-kwon visits the same places in Kangwon he first visited with Ji-sook, and of narrowly missed encounters that might have changed everything: if Sang-kwon instead of his friend had gone to get the beer he would have run into Ji-sook; when his friend, sent ahead to fix a rendez-vous with the girl, lingers because he has to tie the shoelaces of the Nikes he bought especially for the trip, the girl departs, meets the shady guy and enables the fatal encounter that could have been avoided. I’ll come back to this ‘counterfactual’ aspect of Hong’s cinema in my discussion of Virgin Stripped Bare By Her Bachelors.

Many of Hong’s narratives share the same bifurcated structure with parallel protagonists, synchronized plot lines or mirroring motifs, but while Kangwon Province present its interlocking halves in sequential order, the later Hahaha presents the recollections of two old friends, film director and professor Jo Mun-kyung and his critic friend Bang Jung-sik, as intercut stories. The two friends meet in a bar in Cheonggyesan Mountain around Seoul before the director leaves to go live with his aunt in Canada. The director’s voice-over informs us that they both went to Tongyeong recently and decided to swap stories over drinks (a toast for a memory, the cutting back and forth between the different accounts announced by “Cheers!”). The basic structure of Hahaha is the classical schema of the frame narrative with recounted flashbacks of multiple characters, but Hong’s more modernist intentions become immediately apparent when we realize that the framing scene is presented as a series of black-and-white photographs with the protagonists’ recollections heard in voice-over. As in Rashomon (1950), the classic locus of multi-perspectivism, the characters’ restricted narration offers limited, biased, unreliable knowledge of the events that took place. Hong adds to the epistemological relativism of the ‘Rashomon effect’ the double helix structure of intertwined synchronized strands held together by specific bonds: it turns out that, unbeknownst to each other, they were involved with the same group of people and were at Tongyeong at the exact same time (their different stories actually neatly follow each other in time). The central bonds are two familiars, the director’s divorcee mother, who has a fish restaurant in Tongyeong, and the critic’s poet friend who has moved to the city from Seoul and is a regular at the restaurant. The poet has two girlfriends, a pretty girl who works at the restaurant and a kooky tour guide Seong-ok who works at Sebyong castle. The critic meets both women and the director will end up pursuing them. Like Sang-kwon and Ji-sook in Kangwon, the director and critic never cross paths, and talk about people the other knows but doesn’t seem to recognize from the tale. Their recollections — which combined constitute a more or less full chronology of their movements during the sojourn in Tongyeong — constitute a thematic commentary on social façade (both cheerful drinking buddies are actually depressed, self-hating and disillusioned), create suspense (we know more than the characters do) and, as David Bordwell has argued, formulate a kind of response to the rise of network narratives (the lack of awareness of their part in a larger mosaic characters in this type of narrative typically show, is here played for humor at the protagonists’ expense).

Variations sur le même t’aime (Merci, Paris-Match!)

Three of Hong’s first four films share a bifurcated structure. Virgin Stripped Bare By Her Bachelors (2000) uses this structure with the greatest degree of formalist self-consciousness. The film is actually divided into five titled parts, each introduced by a fade to black, but parts two and four, ‘Perhaps Accident’ and ‘Perhaps Design,’ constitute the bulk of the narrative and are subdivided further into seven numbered sequences. Parts one and three correspond to the frames attached to Jae-hoon and Soo-jung respectively. The first part, ‘Day’s Wait,’ is attached to Jae-hoon who waits an entire day in a hotel room for his lover Soo-jung to appear and gets a phone call saying she’s not feeling well. We then flashback to see the chain of events that led to the hotel room: Soo-jung and her boss, the filmmaker Jung-soo, meet his former classmate Jae-hoon for lunch at his art gallery; Jae-hoon runs into Soo-jung at the palace across from the gallery where he is looking for his gloves, which Soo-jung has found by accident; Jae-hoon decides to finance Jung-soo’s film and falls in love with Soo-jung, who tells him she is still a virgin; the trio meet again at a birthday party thrown by Jae-hoon’s friend; Jae-hoon looks for Soo-jung in Goyang, where she’s visiting with some friends; they try to make love in a hotel room but decide to try it again somewhere nice, like Jeju Island. At this point, we assume that the hotel in the opening scene is in Jeju. The film then returns to the present with Soo-jung’s frame, ‘Suspended cable car,’ for a second large-scale section again divided into seven sequences that resumes some of the scenes from part one (another instance of replay) but fills in bits of information skipped over in the first part, the result of Soo-jung’s point of view: Soo-jung is a writer; Jung-soo has a family; he’s in love with her; Soo-jung is sexually abused by her older brother; she’s suffering from depression.

This folding into each other of the two parts of the backstory before the outcome is finally shown in part five, has encouraged film scholar Marshall Deutelbaum to take exception to critics reading the film as merely another essay in perspectivism and the ambiguity of memory. If you cut and paste the different segments back together again, Deutelbaum argues, you will discover a fundamental linear chronology. But the play with temporality, in a way, is the whole point. Virgin set the template for unmarked flashbacks (Woman Is the Future of Man, The Day After, Claire’s Camera), uncertain timeframes (Hahaha, The Day He Arrives, Claire’s Camera) and the wacky temporality of parallel worlds in Right Now, Wrong Then and The Day He Arrives. In Hill of Freedom, in which a character reads a book called Time, the story events are shuffled in a flashback structure that mimics the scattered letters from her lover Mori that Kwon reads in the frame story. Movies like Hahaha and Oki’s Movie challenge the viewer to come up with a coherent chronology of events. In the latter, divided into four episodes, the first episode, ‘A Day for Incantation,’ marking the three protagonists as disillusioned, cynical or depressed, actually comes last in the timeline of the story, while the seemingly inconsequential poetic interlude, ‘After the Snowstorm,’ showing the freshness of initial encounters, comes first. We have to pay attention if we want to ascertain the exact amount of time that has passed between these episodes, the last of which is presented in the form of a fiction in the fiction, as in Tale of Cinema. In Claire’s Camera, the opening stutters back and forth between the time of Man-hee getting fired (the timeline that starts the movie) and a ‘present’ three days later. A scene of So and Man-hee at Cannes party that seems like another flashback is impossible to place with any certainty in the chronology.

Deutelbaum’s focus on Virgin’s chronology appears too narrow, however, when he tries to find chronological reasons for the film’s play with minute variations or tweaks, some related to content (Jae-hoon is richer in the second part, which explains destitute Soo-jung’s reaction to him; in the first section she is chosen by Jae-hoon, in the second by Jung-soo; in the second section she is drinking more heavily), some mere jokes (different men rushing to the bathroom during drunken lunches, dropping chopsticks then napkins, mirrored shots of the drunken party waiting for a taxi), others formal variations that seem to belong to the realm of what Bordwell has termed parametric narration, stylistic variation independent of plot. Bordwell’s two main examples of this style-focused form of narration, Bresson and Ozu, are two of Hong’s favorites. Bresson’s basic stylistic strategies are very close to Hong’s: sparseness, precision with limited resources, belief in setting up your film while shooting, play with onscreen/offscreen space, reflection on how to shoot and cut character interaction, ellipsis and repetition. The difficulty in determining precisely how much time elapses in the story is another narrative choice Hong shares with Bresson, as is the confined view created by the voice-over interjecting reports on the character’s actions or mental state, and the narrative frame of the diary and notebook. The playful changes recall Ozu (as do the moderate or excessive bouts of drinking and the reprise of muzak themes that signal the beginning of another episode or variation): items of setting that disappear or change position from scene to scene, teasing us to recall an earlier moment in the film. Like Ozu, Hong makes a fetish out of American commodities like bottles of Johnny Walker Red and Blue, Marlboro Red cigarettes, and baseball caps. Like Ozu and Bresson, Hong likes to limit the devices at his disposal, reducing the number and types of settings, the possible angles of view, the number of shots per scene, the type of shot transition or camera movement, so we can notice the smallest difference.

The film closest to Virgin is The Day He Arrives, another film that reflects on chance versus design and that shows us different versions of extremely similar sequences that seem to exceed narrative motivation: some of the repetitions have the exact same framing and audio, while other show subtle shifts in framing, staging, gestures, and textural detail (for a close comparison between the ‘five days’ in the film see Kevin B. Lee’s terrific video essay, ‘Viewing Between the Lines’ ). Like Virgin, The Day He Arrives was shot in black and white. In an interview on Virgin cited by Deutelbaum he explains the motivation behind that choice:

In this film I wanted viewers to be able to distinguish the very subtle differences between two identical scenes. For example, in one scene a character drops a spoon. And in another it’s a fork. I thought that by using black and white and insisting less on the distractions of color viewers would be better able to distinguish the differences.

Another film constructed around repetition and variation, Right Now, Wrong Then offers a replay of the same situations and set-ups. The film is again split in two parts, providing two counterfactual versions of the central love affair between the arthouse filmmaker Ham Cheon-soo and the painter Yoon Hee-jung. In both stories the protagonists meet at Hwaseong palace, visit the painter’s studio, end up drinking at a sushi place and drunkenly attending a party at a friend’s house, but the meaning of these scenes is completely transformed by narrative adjustments (Ham is a day early in Suwon, not to seduce an assistant, but because the organizers made a mistake), changes in dialogue and temperament (Hee-jung is less depressed and more assertive, Cheon-soo more considerate) and expressive nuances in acting (intonation, posture etc.). Even the opening credits are repeated and morphed about an hour in: “Right Then, Wrong Now” becomes “Right Now, Wrong Then.” This sets up a weirdly looping timeline between these two parallel worlds, which Hong has said should not necessarily be taken as the incarnation of two different points of view. In the Cinema Scope interview he talks about the central conceit of Right Now as “an infinite possibility of worlds”:

Just look at these two circles in the drawing as two independent worlds. If you believe there’s a clear reason for these two worlds to exist, once you find a clear meaning between them, then these worlds themselves disappear. Once we make clear sense out of these two worlds, they are just used up. It happens that it’s not easy to give them a clear meaning. So all the questions are kept alive if there’s an infinite possibility of worlds. It’s like a permanent reverberation.

The logic of infinite worlds brings to mind the principle of the ‘forking-path’ narrative that is named after Borges’ famous spy story, ‘The Garden of Forking Paths’ (1941) in which mention is made of the learned Ts’ui Pên who has constructed an infinite labyrinth and composed the ultimate Gidean ‘chaotic’ novel, a book which has the possibility of continuing indefinitely:

In all fictional works, each time a man is confronted with several alternatives, he chooses one and eliminates the others; in the fiction of Ts’ui Pên, he chooses — simultaneously — all of them. He creates, in this way, diverse futures, diverse times which themselves also proliferate and fork… He believed in an infinite series of times, in a growing, dizzying net of divergent, convergent and parallel times. This network of times which approached one another, forked, broke off, or were unaware of one another for centuries, embraces all possibilities of time.

Hong more or less illustrates the principle in In Another Country, in which a bored writer tries out three different versions of a simple script: a French woman visits a coastal town. In the first she’s a successful French director, in the second she’s a rich housewife from Seoul, in the third she has been left by her husband. In the three stories she goes looking for a lighthouse and Hong gives us three variations (different shot size, different clothes, different weather) on a shot of her standing at a fork in the road.

The idea of infinite worlds possible is mostly what has made Hong’s reputation as a postmodernist filmmaker and has drawn comparisons to films like Lola Rennt/Run Lola Run (Tom Tykwer, 1998), a film that also presents its possible futures or outcomes seriatim by returning to the same switch point. The film historian András Bálint Kovács sees Lola Rennt as a typical instance of postmodern “virtuality”:

Every event is a version of an infinite number of virtual alternatives that are plausible and necessary the same way as the one that became reality, just like in a computer game. And the reason why one of the equally possible alternatives becomes reality is pure chance.

In a perceptive piece for Reverse Shot, the critic Nick Pinkerton expresses a similar concern with the casual nature of Hong’s ‘games,’ sensing, perhaps, a lack of commitment (more moral than aesthetic), a general cynicism about (the power of art) and life:

The incremental adjustments he makes from film to film give little sense that the 56-year-old is working toward his chef d’oeuvre or building to anything in particular. In fact, the movies seem to turn away from the very idea that there is anything to build toward, in either life and in art: things happen and then more things happen. Even his ‘sliding door’ alternate narratives diminish the power of causality: things happen, but things might happen in another way, but then it wouldn’t make all that much difference if they did.

I want to add two points to this discussion, the second of which I’ll develop more in my next blog. The first is that the idea of forking paths — of (flashback) replays as story variations that do not adhere to traditional ideas of causality or primacy (in the sense that the second variation is seen as a ‘correction’ of the first) — was most influentially incarnated in cinema history by L’année dernière à Marienbad (1961), a film with close ties to Borges (screenwriter Alain Robbe-Grillet admitted that many of the ideas for the film were taken from The Invention of Morel (1940), a ‘fantastic’ story by Adolpho Bioy-Casares, a student and close friend of Borges). If Tony Rayns chides “lazy critics” for clinging to the comparison between Hong and Rohmer, he prefers the one to Alain Resnais. Rayns adduces evidence for the link to the nouveau roman by quoting Korean filmmaker Bong Joon-ho who has pointed to the similarity between Hong’s play with repetitions and variations and Jang Sun-woo’s Road to the Racetrack (1991), an adaptation of a nouveau roman by Ha Ilji, a literary enfant terrible educated in France and commonly seen as an important inspiration for the New Korean Cinema. The nouveau roman comparisons certainly draw support from a commonly cited Hong quote: “People tell me that I make films about reality. They’re wrong. I make films based on structures that I have thought up.” Hong’s ‘structures,’ the technique of repetition and variation, the slightly incompatible replays of a central event, the accumulation of narrative frames and the seemingly endless deferral of meaning in Hong’s most self-consciously modular films, certainly brings to mind the nouveau roman and the conflicting repetitions of L’année dernière à Marienbad. (Let’s remember that in The Day He Arrives the central location is a bar called “Novel”!) That film that has been seen as either post-modernist or high-modernist depending on whether you take the presented alternatives in the film as endlessly proliferating side by side or whether you take one to be ‘true’ or ‘real.’

But even if Robbe-Grillet vigorously denounces the latter option, you could still argue that, certainly for Hong, the techniques of the nouveau roman belong to the modernist legacy. Take a closer look at the chapter titles of Virgin and Oki’s Movie. At least two of those titles, ‘A Day’s Wait’ and ‘After the Storm,’ were taken from Hemingway short stories. While I’ve already referred to the importance of Hemingway at the level of characterization, mood and Hong’s ‘laconic’ style, these specific story titles — which have nothing to do with the storyline of either film — refer us to the collection in which they were included, Winner Take Nothing (1933), that also includes ‘Homage to Switzerland,’ a very Hong-like story about train stations, drinking, sex and flight from the self. ‘Homage to Switzerland’ is one of Hemingway’s most formally inventive efforts: it has a three-part structure and features three protagonists, Mr. Wheeler, Mr. Johnson and Mr. Harris, each with their own story block. All of them are expatriate Americans who are waiting for a train at a different Swiss railway station. As it turns out, they are all waiting for the same train. Each part begins in almost exactly the same way: 1 – “Inside the station café it was warm and light. The wood of the tables shone from wiping and there were baskets of pretzels in glazed paper sacks.” 2 – “Inside the station café it was warm and light; the tables were shiny from wiping and on some there were blue and white striped tablecloths on others and on all of them baskets with pretzels in glazed paper sacks.” 3 – “In the station café at Territet it was a little too warm; the lights were bright and the tables shiny from polishing. There were baskets with pretzels in glazed paper sacks on the tables and cardboard pads for beer glasses in order that the moist glasses would not make rings on the wood.” We don’t need to elucidate the minute differences between the three openings, or even pause to consider the thematic importance for Hong of three different characters being, metaphorically speaking, the same man. My point is simply that there is very little in the nouveau roman that was not taken from Hemingway, Faulkner, Joyce and Gide, in other words, from literary modernism, which is where all of Hong’s literary influences come from.

My second point takes off from David Bordwell’s enlightening chapter, ‘Film Futures’ (from Poetics of Cinema, 2007), in which he argues that there is very little evidence (or danger) of Borges’ endlessly proliferating story times showing up as actual narrative strategy in even the most playfully self-conscious of contemporary films. What is most often the case is that instead of an infinite, radically diverse set of alternatives, we have “a narrow set both in number and in core conditions.” Also: “All paths are not equal; the last one taken, or completed, presupposes the others” and “what comes earlier shapes our understanding of what went before.” The idea that, “Sometimes a film suggests that prior stories have taught the protagonist a lesson that can be applied to this one — thereby footing any sense that parallel worlds are sealed off from one another,” can also be seen to apply to Virgin and Right Now, Wrong Then. In the Cinema Scope interview Hong strongly denies that there is something like a ‘moral’ primacy between the two halves of Right Now, Wrong Then:

In comparing these two parts, if I can call them parts, some elements can be well connected, and make the audience feel that they can explain the difference between the two in terms of morals and attitudes. But some elements are not meant to be like that, and the two worlds are meant to be quite independent. If one is able to offer a clear explanation about the relationship between the two parts, then that can be a pleasant thing. But that encloses everything…You know what I mean? This way we can proceed with some pleasure of making sense, but still feel that the two parts are quite independent. Not one moralistic message.

Hong’s comments, I think, must be taken in the context of the delicate balance looked for in his work between the particular and the general, sketched at the beginning of this essay. But to say that there is no moral hierarchy between the two parts (if you can call them that) of Right Now, Wrong Then, is not very serious. Consider in this light the final section of Oki’s Movie, also titled ‘Oki’s Movie,’ that presents a young woman’s point of view on her relationship with a fellow student and with her older professor. She presents two walks — the first on December 31 with the older man, the second on January 1 with the younger man — side by side to help her make a choice, which for her is the reason for making her movie: “Things repeat themselves with differences I can’t understand. I wanted to see the two side by side.” That’s moral evaluation. If Hong is not a moralist in the classical didactic sense of wanting to instruct, or in the Christian-Catholic sense of his favorite authors, Gide, Dostoevsky, Bresson, Dreyer, Rohmer, Ford, then he is certainly a master of moral comedy, like Rohmer (who has also said that he has no moralizing intentions) and his French masters in the genre, from Pascal and Rochefoucauld to Corneille, Balzac and Renoir. In my next blog, in which I’ll take more about Hong’s romantic comedies, Lost in the Mountains, Our Sunhi and Yourself and Yours, and introduce a comparison to Hong’s friend Matias Piñeiro, I will treat moral comedy primarily as a type of storytelling. I will again make reference to Rohmer, whose practice, throughout the three series in his filmography, ‘Moral Tales,’ ‘Comedies and Proverbs’ and ‘Tales of the Four Seasons,’ of creating resemblances or different outcomes to similar psychological scenarios is primarily a way of composing a plot: “Moral Tales is simply a means of stressing the tale side, the narrative side, the story — that I used in a slightly more systematic fashion.”