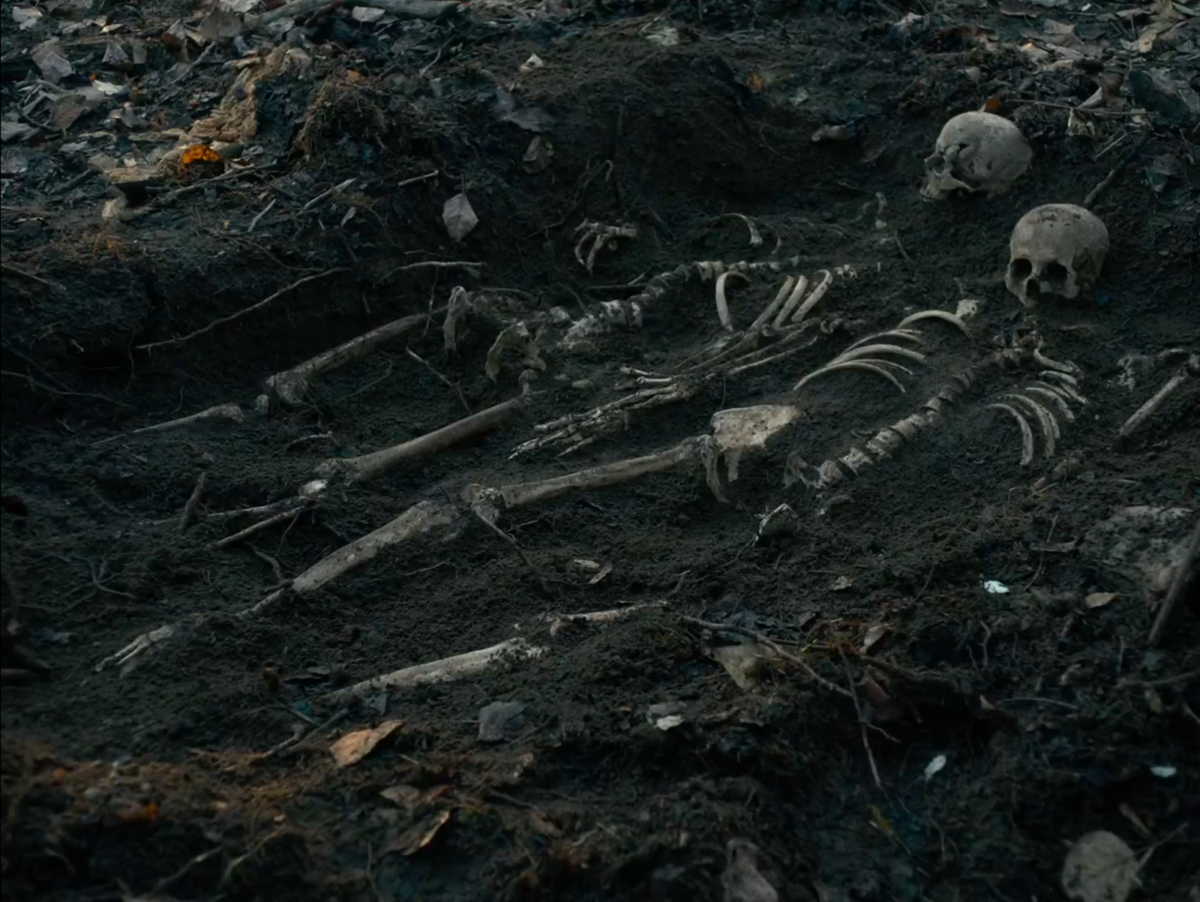

Rather mystifyingly, Kelly Reichardt opens her period-piece First Cow (2019) in what seems to be present-day Portland. An ostensibly modern ship drifts slowly into view, sailing down the Columbia river—a once key trading route used by settlers arriving in Oregon. The mundanely dreary grandeur of this obvious offspring of industry is undermined when the film cuts to a more low-key sequence of shots of a dog and its owner—a woman wearing a nylon jacket which is cleverly juxtaposed with all the fur coats we’ll see men in 1820 wear. This lively duo, while serving as a nice little wink to Reichardt’s canine-centric Wendy and Lucy (2008), also jump-starts the narrative by giving the viewer the requisite material minimum for an act of storytelling to take place. They find and dig up two skeletons, while a seemingly old ferryboat, a more communal and outmoded piece of fluvial hardware, floats calmly by, thus subtly introducing the thematic framework of a film that’s going to deal diachronically with companionship and the strange products (and machinations) of history.

After the unnamed woman looks pensively up at a naked tree top and we get a clear shot of the dried-up bones of the protagonists, the film jumps back in time to a forest in 1820, where one of them, Cookie (John Magaro), is foraging for his group of rugged trappers. This transition subtly conveys that First Cow is more of a leisurely made up tale based on a mundanely framed archeological find, rather than a historically driven narrative built around the illusion of facticity. The woman is seemingly telling a story to herself; she’s weaving a speculative account of a male dominated time when dreams of riches and utopia drove men to the Americas where they saw themselves as the subjects of history. In its wake, her unassuming act of storytelling will surprisingly deconstruct this grand historical narrative the settlers naively believed in, not realizing that the New World is neither as new nor as otherworldly as they expected. The traumatic truth that the frontier was not a manifestation of destiny but rather the ever-expanding outer limit of colonization will come to the fore, and the West’s (now debunked) idea of history as a progressive process that ends in utopia will be revealed to be an ideological device employed in the name of conquest and exploitation.

First Cow achieves all of this by exposing the fact that the Western concept of history has more to do with (the acquisition of) space and language than with the actual flow of time. Reichardt makes this abundantly clear when Cookie meets his future friend and business partner King-Lu (Orion Lee), a Chinese man whom he mistakes for an indigenous person who “speaks good English for an Indian.” Taken aback by this misconstrual, the naked Lu—who looks like Adam just after being thrown out of the garden of Eden—is quick to point out his actual ethnic background even though it matters only insofar as it betrays how absurd the grounds for othering indigenous people are. It turns out that the Other of the white man is not defined by any objective (visual) traits but by his place of birth and his relationship with the language of imperialism. In this regard King-Lu is an already integrated minority. He has bought into the colonizers’ dreams and illusions and is ready to try his hand at being one of the first rags-to-riches capitalist subjects; he just needs to endure a bit of racism. This becomes apparent when during a conversation between him and the Maryland-born Cookie, he comes off as paradoxically more in tune with the ideological narrative surrounding the New World than his friend. He off-handedly remarks that everything in America is still new, before adding that this aura of novelty apparently surrounds the things (creatures, plants, landmarks etc.) left still unnamed; a typically Western line of thought which again harkens back to a biblical motif: Adam naming the animals in the garden.

His remark however is undermined visually throughout the film, which features mostly (domesticated) animals and plants that are well-known in the Old World. There are cats, dogs, horses and of course a singular cow, while the clearest shots of plants are close-ups of berries and nuts. The story even begins with Cookie picking up a spectacular yellow chanterelle (a mushroom also native to Europe) while a sweet piano melody conveys a paradoxically homey feeling even though he is in the woods. On the other hand, we don’t even get to see the main economic exploit of the region, the American beaver. (The Eurasian beaver was already getting hunted down to near extinction at that time in Europe.) There are only shots of the beaver’s fur covering the heads of the uncouth, scruffy-looking trappers, which signals that the beaver is disappearing because of them—when Cookie and Lu set up traps they only manage to trap a couple of squirrels—but also functions as a subtle joke because at one point we find out that the beaver hat is “on its way out [of fashion] in France.” It seems that the trappers were (up to this point) unknowingly participating in the latest of bourgeois fashion without any of the benefits of actually being rich. This only goes to show how a commodity’s fashionability and worth are spatially determined and have little to do with its novelty or scarcity.

At the same time, there are animals and plants that are actually native only to that region of North America, but for the most part they appear as pieces of the larger mise-en-scène and they never come into sharp focus. For example, the lush forests surrounding the characters are to a large extent made up of trees and bushes native specifically to the Pacific Northwest, but the film never puts them front and center. Instead the forest comes across as an opaque and confusing place where the characters (and the viewers) can get disoriented and even lost because there aren’t any spatial indices which contextualize it. Furthermore, on the level of the sound design, Reichardt has said in interviews that extra effort has been put into mixing in only sounds of birds (and even crickets) endemic to the region. The opaqueness of these little details, which spring forth only if the viewer is especially attentive, conveys the colonizer’s point of view, which is focused more on what’s commodifiable and not on what’s actually “new” and unique in the space he occupies—that’s why later on in the film Cookie’s pastries will garner so much attention from the camera. In this way both foreground and background are already deconstructing the ideological premises of Lu’s statement about the namelessness of things being tied to their novelty and potential utility. In fact, it seems like the things that already have a name—i.e. are already a part of the network of objects deemed worthy of attention by the history of capital—are the ones perceived as most valuable in the New World.

Cookie in his own right offers a rather meek common-sense rebuttal of King-Lu logocentric formulation by pointing out that to him the continent seems in reality really old. Like the film itself, he subtly challenges the ideological framework of colonization and the way its ideological fixation on the written word eschews the factual truth of indigenous people’s thousand-year-old “prehistoric” oral tradition. Lu however disregards this remark and naively concludes that history still hasn’t arrived in the Americas, which gives him and Cookie the opportunity to be ready when it does, to have accumulated enough wealth before the realities of class struggle set in. The problem with this train of thought and with Lu and Cookie’s subsequent scheme to get a business running by stealing milk from the eponymous first cow in the region, is that theirs is a paradise always already lost. Their crime, albeit justifiable, exposes the fact that history (class, wealth and power) has already arrived. After all, they’re robbing the Chief Factor (Toby Jones), an affluent Englishman with his own personal guard and a capitalistic penchant for calculating everything including grim abstracts such as how much worth one can extract from a slave who has misbehaved and needs to be punished: should he be killed so the others are scared into working harder, or maybe beaten just enough so he can continue to toil for his master afterwards? Even the house of this villainous figure reveals the ‘already-here’ of class in that its unassuming white facade hides a neatly furnished interior, which totally breaks with the spatial and aesthetic homogeneity of the surrounding area where people like Lu and Cookie live in dingy wooden shacks.

It’s important to note that the Chief Factor also espouses a belief similar to Lu’s, that history hasn’t reached America, although for him that is due to the fact that it has started moving too quickly on the old continent. When talking about the rapidly changing fashion trends in Paris, which are pertinent to the trade of “soft gold” (beaver fur), he observes that history has accelerated so much in Europe that it paradoxically doesn’t have the time to manifest itself in any meaningful way across the Atlantic. Here again an ideological prejudice reifies the New World as something wholly other while obfuscating the reality that it has already been plugged into the network of production that lets the flow of capital go round. The film hints that this is done primarily in the name of the senseless exploitation of natural resources. When the Chief Factor is faced with the matter of the dwindling beaver population in Oregon he can only scoff and reassure himself that the soft gold is boundless and that the demand for it will never diminish. While being a caricature of every entrepreneur’s dream of a perfect commodity, this strange refusal to accept reality is also indicative of the ways the ideology of Capital refuses ‘less developed’ civilizations the privilege of being a part of history. This consigns the New World to a sort of pseudo-utopian stasis, which props up the illusion that the resources needed for the ever-accelerating flux of history in the Old World to continue will never run out. The film flips this assumption and shows how the material basis of Western historicism has everything to do with the rapid acquisition and exploitation of new spaces, while the production of time (of trends, events and dates) is an ideological by-product acting as the veneer of progress and change. From this point of view the concept of history isn’t really dealing with Chronos but with the search for vestal topoi where the powers of innovation can run amok, profiting from a delusory endless supply of resources.

Lu, coming from the outside of this ideologically propped up status quo, seems more aware of the realities of scarcity, but he falls back on this clarity, which is a sort of bitter class consciousness, only when it helps him game the system and propel him upwards in the same hierarchy guilty of marginalizing him. (In one scene he points out quite resentful that the cow is of better breed than he is.) He is the one who points out to the Chief Factor that there used to be “whole cities of beaver living in row houses like people in New York,” which are now disappearing, and on several occasions he seems wary of adopting a business plan that someone might have already exhausted. He even seems somewhat conscious of how capital, history and space are intertwined, when he tells Cookie that in “different places” he believes “different things” and that he would open a farm for almonds but growing a tree takes too much time so it’s antithetical to profit. In comes the ‘first cow’, the conceptual focal point of the film, which fully expresses the tensions between old and new, space and time, friendship and business etc. The paradoxical primacy of the bovine in the New World is a function of its location not of its actual novelty. Exactly this fact turns it into the perfect device for accumulating capital although it’s something as old as European culture itself. In the same way that women were scarce—leading to high demand and prostitution being a big part of frontier culture—it’s a playful absurdity that in the “land of plenty” something otherwise as common as a cow gets commodified in a way which gives it an aura of newness. This sudden appropriation and exploitation of what has always been there is what usually gets called innovation and that’s what drives ‘history’ forward. The film critiques and exposes this mechanism in all sorts of funny little ways when Cookie and King-Lu start using the cow’s milk (stolen in the dead of night) to make deep-fried oily cakes for the trappers, who are tired of eating “flower-and-water bread.” When the protagonists get asked what their pastries are made of, Lu, being the clever outsider that he is, says that they used a secret ingredient and that it’s an ancient Chinese recipe. He is a true entrepreneur selling back to the ignorant white man his own culture under the guise of something exotic and foreign of which he has no knowledge.

Cookie, on the other hand, brings a certain innocence to the whole criminal endeavor and seems to be enjoying the beauty of his craft—the simple act of cooking—even though he himself has dreams of opening a bakery or a hotel and becoming a self-made man. What separates him from the Chief Factor and King-Lu is the tenderness he has for the cow and the people around him. He is portrayed as a genuinely empathetic person who is eager to give a helping hand to whoever needs it. (That’s probably why he saves Lu’s life in the beginning of the film.) This affectionate disposition hinders his ability to see the world through a profit-driven ideological lens; his bouts of common-sense offer a real alternative to the way the people around him tend to overestimate their prospects of getting ahead in life. It shouldn’t be a surprise then that the one time Lu, driven by greed and resentment, decides to disregard Cookie’s advice to lay off stealing milk for a while, this ultimately gets them both killed.

Even though their story ends tragically, the relationships Cookie fosters with his friend and the cow, to which he talks lovingly as though she were a person—again creating the feeling that they are in some sort of Edenic place—challenge the prevailing ideological framework of his time and offer a peak of what lays beyond the history of Capital. When they finally get caught, King-Lu has the opportunity to just run away with the money from their little business venture and set up shop somewhere else, thus reinforcing the idea that the good entrepreneur/innovator is always heading towards the next utopianly reified place where he can thrive. His bond with Cookie is too strong however, and he decides to remain with his friend to the bitter end; a radical gesture, which not only sees friendship triumph over business, but also shows Lu choosing to side with a boundless hereafter that spans over and beyond the concepts of history and success that he has adopted from the white man. This choice will paradoxically immortalize the two men in a way they couldn’t have expected—or gained anything from—because without Lu’s sacrifice in the name of true companionship there wouldn’t be a story for the girl in the beginning of the film to tell. So not only in its content but in the act of storytelling itself, First Cow offers a true alternative to the ideologically induced flux of capitalist history by showing how truth can emerge when telling a good (genuine and honest) story, which, like growing a tree, takes time.