As we approached the gathering crowd, it seemed we must be mere moments away from a celebrity exiting a car with darkened windows. With no car in sight, we waited a while. The last time I had walked through this area of the Berlinale together with Ben (one year prior), we happened to pass Machine Gun Kelly, a person I would not have recognized had I been walking alone. We glanced at the gawkers’ paraphernalia to see if we could figure out who they were waiting for and soon noticed prints from E.T. and Jaws. We could hardly believe it, but they were indeed waiting for Mr. Spielberg, certainly a figure of interest during my childhood, but the bane of my existence by adolescence. For years, anytime it was first mentioned to a family friend that I had developed an interest in filmmaking (and later, that I was studying film at university), the same response always came back: I would be ‘the next Steven Spielberg.’ ‘No’, I would think to myself, ‘why can’t I be the next Kubrick?’ But now, to happen to see one of the most famous household names in Hollywood directing completely by accident would have felt almost as funny as running into a rapper whose music I have never heard. We stood around for a while and eventually left without seeing Mr. S. Standing in the crowd, I wondered if this was a film festival. I don’t think it’s productive to pontificate on whether or not those individuals went to see any of the ‘homage’ screenings of Spielberg’s films during the Berlinale—but then again why should they? They were all being screened from DCPs, untouchable data.

Ben and I made our way into the Grand Hyatt and up to the press area, where we found vested and armed police officers waiting in line for coffee. As we got our free coffees I imagined what it was like working the espresso machine in the press area of the Berlinale (since I had the day off from my own barista job) and asked myself if this was a film festival. As we parted ways after coffee (and after perusing the impromptu shop outside Arsenal), I reflected on our morning at Silent Green, taking in this year’s Forum Expanded offerings. Tenzin Phuntsog’s nearly still-life portraits of his parents on gorgeous 35mm (presented as a video loop) was reassurance that cinema continues, despite its death. Walking back to the S-bahn, I ran into Matt Johnson. I couldn’t help myself and stopped to say hello and tell him I’m a fan of Nirvanna the Band the Show, and asked for a selfie because I knew my friend who also likes the show would never believe me without proof. I had no plans to see Blackberry, having already missed the screening that would have fit with my day job schedule. I spent most of my time over those ten days meeting with people who were in town rather than seeing movies. Is a festival the film it shows, the audience it draws, or just the reputation that pulls in both?

The modern film festival seems forever stuck in a loop of self-diminishing returns. Big money constantly weasels its way in among quality works, yet it’s the more sincere films which have to fight for space alongside the products in a festival lineup. In a utopian vision of a festival, the high-concentration of more personal and interesting off-the-beaten-track films would unfurl slowly over a full calendar year instead of playing across 10 manic days. Instead, they all run the risk of falling off into obscurity after their premiere. The fact that no one watching these films in the festival setting has time to fully process anything they are seeing only exacerbates things. The modern film festival demands so much of its attendees who seek the light in earnest, while seemingly offering so little in return, apart from the promise of finding the films that make it worth the time spent braving the muck. In 2015 I approached the Berlinale in total naivete, thinking ‘if a film has made it all the way to the Berlinale, it must be good’. Over the years, after seeing terrible productions in the festival’s competition category (Alone in Berlin (2016) being one of the worst offenders) not only here but in other revered festivals (Brimstone in Venice of that same year remains one of the 20 worst films I have ever seen in my life), I finally learned the hard way that playing in a prestigious festival is not a guarantee of quality—which in retrospect is of course glaringly obvious.

In the specific case of the Berlinale, a change in leadership marked a noticeable uptick in quality for the festival’s program in 2020. My hat’s off to the new team, but even so, a program must always make consolations for money and create a selection based on what is actually available timing-wise.

As I work on this essay, I am witnessing the same routine repeat itself in Cannes. Even in the very midst of writing this paragraph I came across another example of prioritizing money and prestige over artistry (or even human connection between a festival and the artists involved in the films they show): a news story about the festival, an open letter from Víctor Erice about his decision not to attend Cannes this year, despite premiering his first new film in 30 years (Close Your Eyes), and having served on a jury at the 2010 edition of the festival.

Between March and April, pending what the Official Selection Committee decided, I received from the prestigious Quinzaine des Cinéastes section, through its general delegate, Julien Rejl, and Jean Narboni, doyen of specialized French criticism, the proposal to open the Quinzaine in Cannes with my film, in a special session. An event that in previous editions has been offered to established directors, such as Francis Ford Coppola . I immediately wrote to Thierry Frémaux to tell him that if Close Your Eyes was not going to be selected, he would notify me in good time (it is something that is customary), so that I could consider the other options that were offered to the film. In Cannes (Quinzaine des Cinéastes ), and outside of Cannes (Locarno Festival or Venice Mostra). But in that waiting time, Frémaux never gave signs of life. The Quinzaine committee kept offering him for weeks, until the time of their protocols ran out.

Despite the posturing of human connection on Frémaux’s part, even relatively direct communication between individuals is desecrated within the major festival model: human needs are simply less important than capital and status.

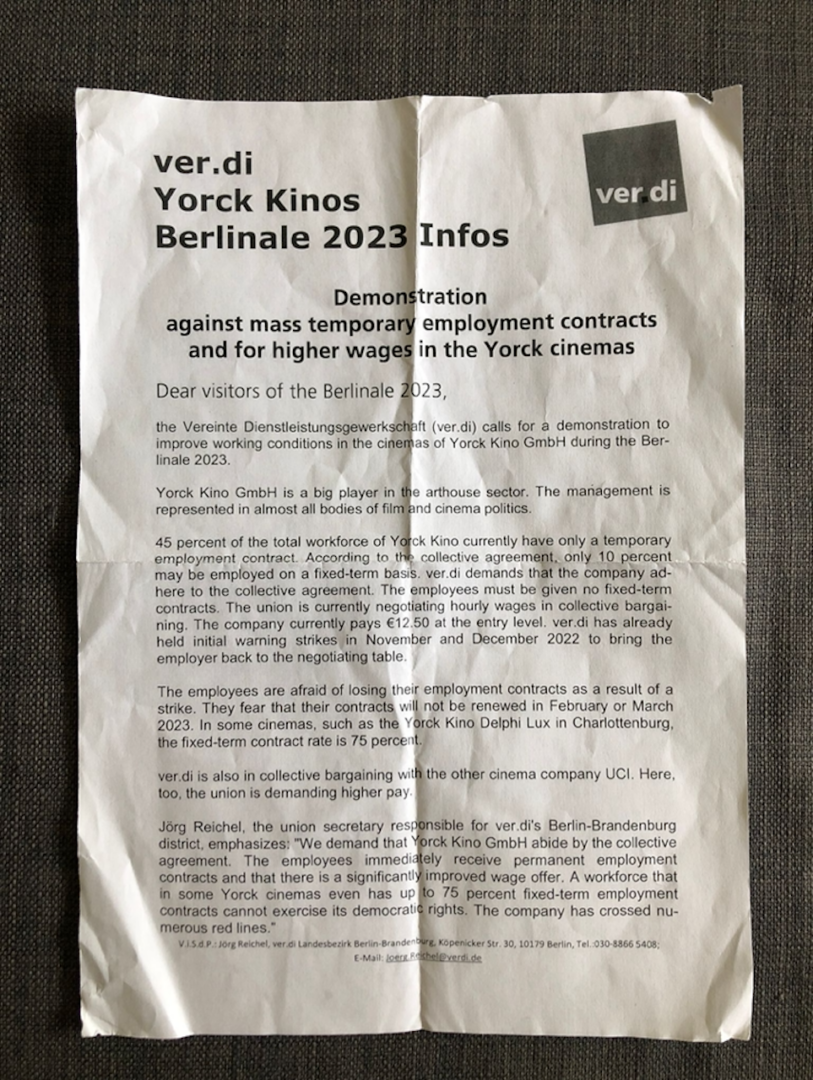

The fact of Cannes’ favor of money is nothing new. But the reality of such an insulting (in)action on the part of Frémaux, alongside an already contentious edition for keeping protests from getting too close to their precious Croisette truly drives home an outrageous self-centeredness. During the Berlinale they managed to at least get information directly into the hands of passersby in Potsdamer Platz:

Seated for Hong Sang-soo’s in water, I opted for the very first row. Since 2020, I still prefer not to be in large crowds if I can help it, and sitting in the very front (when it’s not neck-craningly impossible because they’ve actually allowed for enough empty space between the seats and the screen) helps. I don’t see the crowd during the film. I practiced taking off my glasses during out of focus scenes. Since I caught wind of Hong himself motivating this decision with something as simple as to reflect his own failing eyesight, I thought it might be an interesting experience to compare my own vision to what I could see with my glasses on. They were fairly similar, except that I struggled slightly to read the subtitles without my visual aid. It was the only film I saw in the cinema during the actual festival, and I didn’t care for it. Hong has been one of a handful of directors that have been reliable mile markers in my Berlinale journey. I first started attending the festival in 2015, and over the years certain names would keep coming back. In 2017 Hong first entered my radar with On the Beach at Night Alone, then premiered new titles at the festival again in 2020 (The Woman Who Ran), 2021 (Introduction), 2022 (The Novelist’s Film), and 2023 (in water). In 2018 I was excited about James Benning, who showed new work at the festival in 2017 (Untitled Fragments), 2018 (L. COHEN, alongside a restoration of his 1977 film 11×14), 2019 (glory), 2020 (Maggie’s Farm), 2022 (The United States of America), and 2023 (ALLENSWORTH). In this nearly seven-year run, the only missing year (2021) is the one in which he presented his new film, PLACE, in an installation at his Berlin gallery representative: neugerriemschneider. I did manage to see ALLENSWORTH on the big screen at an early press screening before the festival began. That day at Silent Green, Mr. Benning entered the Forum Expanded exhibit and sat down on a beanbag chair next to Ben and I. He liked Tenzin’s films. I thought he might. Both filmmakers recall the cinematic work of Warhol, the Godfather of slow cinema, idle cinema, working independently, and yet also working constantly.

I saw one other film during the festival, albeit at home, on a screener. It was Samsara, by Lois Patiño. My last encounter with Patiño’s cinema was a 2020 Berlinale screening of Red Moon Tide, which I strongly disliked, largely for its outrageous ending. Samsara, however, is an entirely different beast, in which the slowness feels far more appropriate, as it focuses on Buddhism and reincarnation. There is a sequence in this film in which the audience is asked to close their eyes for a significant period of time. I had had this surprise already spoiled for me (which was also a point of intrigue that pushed me to watch the film) and so fully shuttered all the blinds and turned off the lights, so the light from my television screen would be strong enough. The effect was phenomenal. A series of flashing colors populate the screen, projecting directly onto the viewers’ eyelids.

My favorite films are ones that put me in a flow state. The flow state is one of concentration, full engagement, and feels highly rewarding, motivating, inspiring. Over the last couple of years I have had a great deal of difficulty achieving this state in the cinema—a space which once summoned it reliably. Careful readers might remember my last Berlinale report from two years ago, in which I complained at length about the ‘at-home’ streaming model the festival took on in 2021. Last year’s MLP festival report, in fact, came in the form of its own absence; musical notation for a nap I tried to take after finally giving in to sheer exhaustion. And thinking in terms of music, there was one particular film at this year’s edition that I really wanted to see: Angela Schanelec’s enticingly titled Music. The only screening that gelled well with my work schedule was an early morning press screening. I planned to go but when my alarm went off that morning a choice appeared. I chose to give my body the rest it deserved, and subsequently missed the film. And subsequently regretted it. Nevertheless, I knew it couldn’t be too long before the film opened in Germany, and I was right. On the 4th of May, it opened through reliable arthouse distributor Grand Film, but to the tune of a scandal. As per Dunja Bialas’ report for artechock, aptly titled “No Music”, it seems that the BKM (die Beauftragte der Bundesregierung für Kultur und Medien), a German government organization dedicated to supporting the arts—and which financially supported the making of Music in the first place—decided against offering any distribution support for the film, despite it winning a Silver Bear for Best Screenplay at the Berlinale.

Most alarmingly, Bialas notes:

…a six-member committee with equal representation decides on the allocation of funds. According to insiders, the vote should be 5:1 in favor; if there are four votes in favor and two in opposition, the project is rejected. It’s a shame that, with such strict voting ratios, one member of the BKM board sits on two committees: Andreas Fink, film buyer at Cineplex Germany, decides on both the BKM distribution subsidy, whose aim is “to bring artistically demanding German films into cinemas”, and the distribution and operating subsidy of the German Federal Film Board (FFA), which also has crowd-pleasers like Manta, Manta – Zwoter Teil [an action-comedy directed by German superstar Til Schweiger] in its 2023 portfolio. Does the man wear two hats without having to make a clear distinction between artistic and commercial films?

Or rather, shouldn’t an exclusion rule apply here, to be allowed to belong to either one or the other panel?

Disgraceful.

Music is not the type of film expected to turn much of a profit, which, as Bialas also points out, is exactly why organizations such as BKM exist. And if winning a major prize at one of the biggest (read: most expensive) film festivals in the world—itself already a parade which has as much if not more to do with keeping up appearances and glamor than the films themselves—is not enough of a qualifier to earn state support for an ‘art’ film, then, excuse me but, what is the point of a film festival?

Music moves slowly, with intention. A hint of Straub-Huillet’s materialism and a heaping portion of Bresson. But Schanelec has by now moved into her own plane. Despite my having just done so, a shorthand comparison to older directors is rather pointless. It’s not that her films are Bressonian as much as the fact that she is one of very few filmmakers so interested in working within that particular register—long, quiet, close-ups, unaffected actors, a specific engagement with hands as tools of greater, ethereal forces. Because it is out of step with larger trends in- and outside of arthouse film, one impulsively seeks historical examples to which her work corresponds. Yet her style seems highly instinct driven; one gets the sense while watching Music that events unfold in the way they do simply because it must be this way—and not only because it takes an ancient myth (Oedipus) as a loose structuring element. There is a fatalistic air about Music, which features no dialog until about twenty or thirty minutes in, and even then remains largely mute for the rest of its 108-minute runtime, preferring the ‘music’ of the natural world to that of the spoken word. Events transpire as they were always destined to, which is not unrelated to social fabric of German society and its importance put upon rules.

In Tenzin Phuntsog’s two portraits of his parents, Dreams and Pala Amala [Father Mother], things simply ‘are’ in a similar way to Schanelec’s cinema, though there is less feeling of determinism in such a short space in which so little change appears. Yet, as with Warhol, there is a strength to the material observations being made via an analog format (in this case, 35mm cinefilm). The filmstrip as a physical vessel, transmitting an image of living, breathing people in a specific space across time to the present day. A time capsule, sure, but it’s the physical substance (still present though diluted after transferred to the digital information of a video file) as the means of transport which lends otherwise simple material an elusive specificity.

For another example of existence as song at the Berlinale, take if you don’t watch the way you move, the latest from Kevin Jerome Everson. Watch 12 minutes unfold in real-time, captured on a tangible object. These precious gems are nested within a larger machine, one which I am no doubt privileged and grateful to have access to. Yet every year is a new opportunity to ask again what a festival is and how it serves the moving image. When I roam the streets around Potsdamer Platz I am overwhelmed, reminded that I am merely another human being ensnared by the massive festival apparatus. When I sit with a film by Phuntsog, or Everson, or Warhol, or Schanelec, I am reminded that I am a human, being.