Patrice Toye’s most recent film, Muidhond (2019), opens on a dreary yet sometimes sunny, industrial yet natural setting in Zeelandic Flanders, the backdrop of the equally conflicting inner life of twenty-five-year old Jonathan. As if an attempt to look into a troubled soul, the first peek inside Jonathan’s plain house is shot through blinds, evoking a sense of spying on something kept out of the public eye, something shameful, a taboo. Taboos are exactly what Toye addresses in her films. Hoping to break them, she confronts her audience with controversial subjects. She made this explicit in the Q&A following the Film Fest Ghent premiere of Muidhond (Tench), her adaptation of Inge Schilperoord’s homonymous novel that daringly revolves around paedophilia. Walking a fine line between sympathy and abhorrence, Muidhond tells the story of young fish factory worker Jonathan (magnificently portrayed by Tijmen Govaerts) who has just been released from prison due to a lack of evidence for the charge of a sexual offence against a child. When his curious nine-year-old neighbour girl Elke (Julia Brown) wants to play with him, he immediately finds himself on the brink of a possible relapse. The two meet and become friends, and even though Jonathan desperately tries to fight his feelings, the tension rises to the beat of John Parish’s edgy score.

Patrice Toye (1967) is born in Ghent and graduated at the University College Sint-Lukas in Brussels. Today, she’s one of Flanders’ preeminent filmmakers and teaches at her alma mater, now called LUCA School of Arts. One year after her graduation, she realised her first short film, Tout ce qu’elle veut (1990). Since then she has completed two more shorts, three television films and four features. Giving her work process an air of small-scale ‘family’ affairs, Toye prefers a modest cast of reappearing actors across films and a limited, habitual crew consisting of composer John Parish and director of photography Richard van Oosterhout who’s also her husband. Family dynamics are not only important behind the scenes, they also thematically dominate her work.

Toye’s feature debut, Rosie (1998), focuses on thirteen-year-old Rosie’s troubled relationship with her mother and uncle Michel, who turns out to be her father and whom she tries to kill. The whole film is narrated in a flashback structure bookended by Rosie being detained in a bleak juvenile detention centre. Ten years after the first film, actors Frank Vercruyssen and Sara de Roo reappear as husband and wife in Nowhere Man (2008). Tomas, a married official in his forties, feels trapped in his so-called successful but conventional way of living. His unkempt, weed-infested garden complements his lack of joie de vivre. Tomas leaves his wife, stages his own death and sets off for an island under a new identity, only to decide he wants his former life back and to return after five years. In a new relationship but only slowly getting over Tomas’ death, his wife locks him into a flat, hoping that Tomas’ sudden resurrection won’t mess up their lives. The protagonists of Toye’s third feature are similarly hidden away and cut off from the world. Little Black Spiders (2013), set in 1978, is an adaptation of Ina Vandewijer’s homonymous novel and focuses on a group of teens who have been sent to a secluded nunnery to cover up their pregnancies. Living together and supporting each other, the girls become an ad hoc family. Only gradually they find out that their babies will be taken away for adoption after birth. Family issues surface here in multiple ways. Do the girls want to start a family of their own? Do they still love their families who have sent them away?

Toye has juggled her artistic career with raising two daughters, and motherhood more specifically holds a central place within her work. She particularly portrays mothers coping with difficulties in taking care of their children. In Rosie, the mother doesn’t care too much for her daughter and finds her own love life more important. When Rosie asks her mother’s attention after she’s been hit by a car, her self-consumed mother not even turns her head to see what happened. We learn that Rosie’s mother got pregnant as a teenager and obliges Rosie to call her “sister” instead of “mama” to conceal this truth. The theme of teenage pregnancy moved to the very heart of Little Black Spiders. Schoolgirl Katja (Line Pillet) is pregnant with a child by her Latin teacher (Wim Helsen). While she has never known her own parents, she feels a strong urge to become a mother herself and desires to keep the baby. Her chain-smoking friend Roxanne (Charlotte De Bruyne), on the other hand, loathes the baby that’s growing inside her.

With teenage pregnancy, both Rosie and Little Black Spiders tackle one of the many taboo topics that are at the heart of Toye’s films. Rosie also deals with poverty, incest, murder and psychological problems. Next to teen pregnancy, Little Black Spiders addresses abortion and rape. In Nowhere man, Toye approaches the issues of depression and suicide. Toye doesn’t shy away from these social problems. She digs into taboos and makes the viewer look at them, intensely, by putting them at the core of her work. Rosie and Little Black Spiders were shot on 35mm, which Toye believes to bring the viewer closer to her characters as well as to represent their vulnerability and intimacy, as the intrinsic brittleness of the film stock embodies their frailty.

The taboos inherent in Toye’s repertoire all tie in with her characters’ states of confinement. Rosie is kept in check by her mother’s brother/her father. His meddlesomeness makes her feel so sick that, dry-eyed, she sets out to cause his death. Rosie is also confined to herself, to the body of a thirteen-year-old, while she desperately wants to be older. Trying to emulate an adult, she starts drinking, smoking and even kidnaps a baby (another problematic mother-child relationship comes up here). Nowhere Man’s Tomas is imprisoned in his dreadful life, locked in a depression. After having run away from it all, he finds out that the island, of which its borders literally restrict him, depresses him even more. Fences marking the boundaries of their domain, the girls in Little Black Spiders are confined to the hidden institution where they ended up because of the taboo that surrounds their pregnancy.

It’s not only a stigma or taboo that confines Toye’s characters, but also their own personalities, which they fruitlessly try to escape by fleeing into the mythical, the surreal, or the own imagination. Rosie struggles to be a thirteen-year-old and tries to escape from her difficult family situation in an imaginary world by impersonating a fictional tsarina from an obscene novel. She changes her hairstyle, puts on blue eye shadow and red lipstick, and steals heels to look like a lady. She finds the desperately desired love and freedom in an imaginary boyfriend. Ultimately, she swaps her lady-like shoes for her roller skates again—an act that represents her inability to escape childhood. Tomas, the nowhere man, is also bound to his identity as an ordinary, middle-aged man living a settled and monotonous life. The island that was supposed to be his refuge did not turn out to be as magical and mythically perfect as he imagined. Eventually, he returns to his old city-life, as he realises that he cannot escape who he really is. In the apartment where his wife locks him up, he’s seen sitting in a room full of sand. This surrealistic scene seems to suggest that he can’t let go of his experiences on the sand-covered island, leading us to the essence of his character, his inability to set himself free. The girls in Little Black Spiders try to escape reality by performing a mythical play in a candle-lit attic, all completely losing themselves. A magical atmosphere veils the scenes in which the girls try to forget about their tragic fates. Yet, time after time, fierce daylight forces them back into reality.

John Parish’s liberating rock music adds to the transcendental aura of the short-lived scenes that burst with a sense of freedom. The energetic electronic guitar chords that underscore Rosie and her boyfriend running through the streets of the Antwerpian Polder town after their mischievous behaviour, powerfully highlight their sense of release. Dressed in sweaty plastic costumes, the Little Black Spiders-girls go crazy during their sensual, ritual-like performance of the Greek Minotaur myth. When they try to transcend the music that becomes more and more intense and reach an almost orgasmic climax, they can imagine being free, as if in a liminal moment.

The recurrent theme of liminality in Toye’s repertoire is inseparable from her characters’ identities. Rosie portrays the liminal phase from child to woman. We see her half-naked in the detention centre bathroom, wearing a mini-bra, which draws our attention to her developing breasts. The idea of a border also resonates with her place in society. She and her mother live in a worn-out working class apartment block that is clearly located at the margins. Also situated on the border of society, the institution in Little Black Spiders is an in-between space from being pregnant to giving birth. The girls’ stay in the institution is only temporary. “Away from the rest of the world for a while. Afterwards, it will seem as if this never happened. You’ll very soon forget about this,” Soeur Simone (Ineke Nijssen) tells them. For the duration of their pregnancy, they are excluded from society, fences forming the border between their domain and the outside world. ‘Nowhere man’ Tomas resides in a typically Flemish, family-friendly but dull suburban neighbourhood, complete with driveways and front yards. His journey from city-life to island-life and back to city-life corresponds with his transition from being alive, dead and alive again.

Death plays an important role in Nowhere Man, often reflected in the presence of insects: a bug drowning in beer, a fly zooming over a dead horse etc. A focus on insects notably returns in every one of Toye’s features, carrying metaphorical meanings. A solitary woodlouse endlessly creeping over Michel’s face after Rosie makes him fall of a dilapidated industrial construction in an attempt to kill him, makes us see him as the dead wood these bugs mostly resort to. The insects in Little Black Spiders also metaphorically represent taboo as the crawling of the little black spiders on one of the girls’ loins is not only a surrealistic signpost ever since Buñuel’s Un Chien Andalou (1929), but also alludes to an unwanted intrusion of the girl’s intimate area.

These features, characteristic for Toye’s repertoire, all re-join in her latest picture Muidhond. A problematic mother-daughter relationship returns in Jonathan’s neighbours, with Elke being neglected by her indifferent mother. Elke’s mother leaves her nine-year-old home alone with no-one to look after her. When she falls on the asphalt drive way while (mirroring Rosie) roller skating, Jonathan hesitates. Should he come near her to help? Red traffic lights in the back ironically signal that this is where he should stop, but really caring for frolicsome Elke, he decides to cross the line and help. Later on, he teaches her how to swim, gives her food and brings her to bed. It’s as if he becomes an ersatz parent for Elke. Toye portrays Jonathan as a human being and not as the monster that a paedophile is generally seen as.

The viewer’s indecisiveness between affinity and aversion for Jonathan and his behaviour is reflected in Muidhond’s photography, which is heavily influenced by American contemporary artist and photographer Todd Hido (who was present during the shoot). Balancing close-ups and wider shots, Toye juggles proximity and distance, recalling Hido’s Intimate Distance, a prominent source of inspiration for Toye and her DOP Richard van Oosterhout. In Hido’s photographical work, the rigidity of clean-cut architecture contrasts with the haziness of light seen through fog. This visual style returns in Muidhond’s similar choice for a rigid and cold setting and penchant for the use of anamorphic lenses and soft focus. The overall feel of desolateness Hido’s work emanates, reappears in Muidhond’s minimalistic setting.

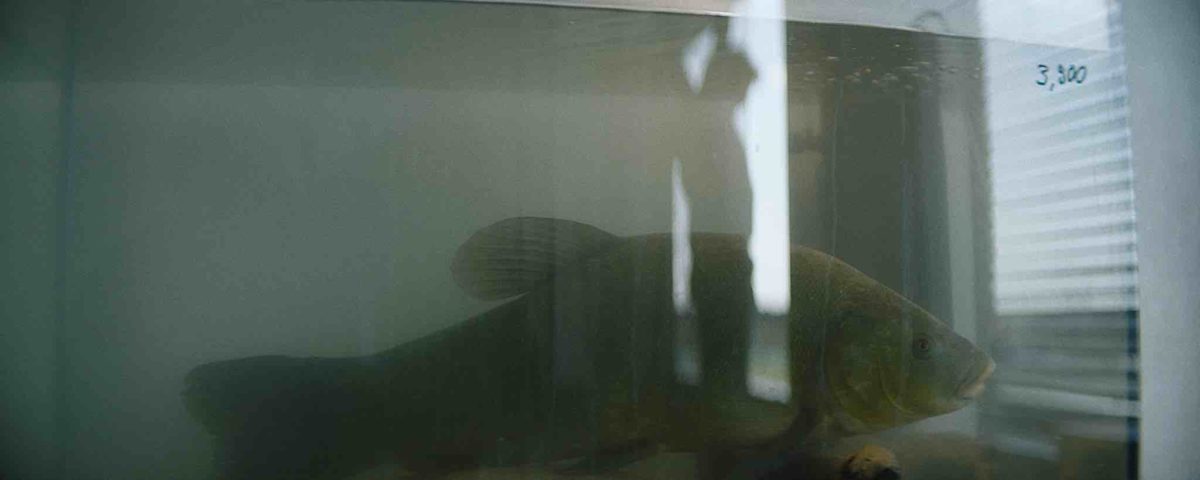

The dreary environment where Jonathan lives is situated in between society and nature, an element that also recurs in Todd Hido’s work. Literally, as much as figuratively, Jonathan is situated on the border of society. This is only one of the many metaphors Muidhond bristles with. Just as the lonely tench in his undersized aquarium, Jonathan cannot escape. He cannot break free from his own being, his temptations. “I’m scared, scared of myself, scared of my thoughts,” he reveals to his psychologist. Similar to the characters in Toye’s other three feature films, Jonathan attempts to escape his own identity by tapping into the mythical. The tench is believed to have the magical power to heal wounds. Jonathan’s special care for this fish he adopted, suggests that he might silently hope to be healed by it. The state of transition from Jonathan’s release from jail to reintegration in society is metaphorically underlined by the fact that he and his mother will move into a new flat. Their apartment getting emptier adds to an atmosphere of bareness that dominates the film. Lastly, echoing Jonathan’s desperate endeavour to wash away his stigma, the motive of water shows up regularly throughout the film: Jonathan washing his face, swimming or taking a bath.

With Muidhond’s focus on the controversial issue of paedophilia, Toye continues her tradition of depicting deep-seated taboos. Her choice of topic and her goal seamlessly blended with Film Fest Ghent 2019’s theme of taboo breaking. “What taboos are actually broken by adding another entry into the canon of films that deal with pedophilia?” my fellow young critic Ben Flanagan wondered in his review of Muidhond. By focusing the camera on Jonathan, scrutinizing his every emotion and sometimes even slightest muscle movements in close-up, Toye opens the blinds and makes us really look at him. Without decriminalising paedophiliac practices, she moves away from demonising perspectives on paedophilia by exploring Jonathan as a sensitive, good-hearted human of flesh and bones. But is Belgium, marked by the severe national trauma of the Dutroux case that closed in 2004, ready to see a homegrown paedophile as protagonist on the big screen? Muidhond winning the FFG 2019 Audience Award seems to indicate that the nation has bounced back —although Tijmen Govaerts’ youthful, good-looking and not-your-stereotypical-paedophile appearance might have helped to open some eyes.