“Is this a ‘positive’ image?” In Color Adjustment (1992) Marlon Riggs juxtaposed a portrait of Bill Cosby with this question, criticizing The Cosby Show (NBC, 1984-1992) for reifying dominant culture without questioning the homogenization of the black community that fed the white gaze and its stereotypical expectations. Barry Jenkins drops the question mark in his own work, thirty something years later. With his third feature If Beale Street Could Talk, following the critically acclaimed Moonlight (2016), he’s putting the representation of black masculinity and the urgency of radical and liberating black love once again on the table. These themes are as central to Riggs’ film as they were to the novel by James Baldwin that Jenkins adapted for his latest film. Unfortunately, they are also as relevant today as they were in both men’s lifetimes.

It comes as no surprise then that this year’s Sundance Film Festival, which has recently come to an end, has put forward several directors doing their bit and following Jenkins’ lead in terms of (re)imagining and challenging representation, just like Sorry to Bother You (Boots Riley, 2018) and Get Out (Jordan Peele, 2016) had set out to do at previous editions of the festival.

The Last Black Man in San Francisco, the semi-autobiographical first feature of Joe Talbot, tells the story of Jimmie Fails, his childhood friend and co-writer on the project. Jimmie plays himself against the backdrop of San Francisco’s rapidly gentrifying Fillmore District, the Harlem of the West where, through the lens of Talbot & Fails, timelessness is drenched in nostalgia. Not having a place of his own, Jimmie obsesses over the Victorian house his family once lived in. With the help of his loyal friend Mont (Jonathan Majors), he tends to the house even though an older white couple moved in years ago.

Talbot captures the tenderness of their friendship as the two men spend the night in Mont’s bedroom. With Jimmie on a makeshift bed next to Mont’s, the scene echoes sleepovers where best friends talk for hours in the intimacy of darkness after curfew. Their age is never mentioned, nor is their sexuality. Therein however lies the essence of Talbot’s choices in terms of representing these two young black men in an urban context. The conscious omission is exactly what makes it a liberated representation. The characters aren’t solely defined by their age, sexuality or color of skin. As quirky outcasts, they are multi-layered and complex characters.

They’re free of labels. But they are only as free as the socioeconomic dynamics of the brutally gentrifying urban environment of San Francisco allows them to be. The limitations of their freedom is clear from the opening scene on. In it, a black little girl looks up to a white worker in a HAZMAT suite collecting samples of toxic matter in the water; standing on a soapbox, a street preacher without an audience rails against the pollution of the Bay. Sitting at the bus stop in front of the man, our duo abandons the idea that a bus will ever pick them up (one of many references to the everyday life of San Francisco natives). We see them skating away from their neighborhood, from the empty, polluted outskirts to the predominantly white inner city, a slow-motion ride down the hills of the city, insisting on their temporary freedom to move through the different landscapes of the neighborhoods and the different populations inhabiting them.

Though they share the same oppressions, as outcasts they’re infinitely freer than their childhood friends who seem to perpetually hang out on the street-corner. A group of thug-like men, which Jimmie used to be part of before hanging out with Mont, trapped in their own tiresome performative masculinity. Mont, as an aspiring screenwriter, constantly observes them and notes down their behavior for his long-gestating first play. Seen through his eyes, the male bravado becomes a grotesquely exaggerated spectacle, a senseless cockfight in the arena of the streets. The space they occupy is hopelessly void of love or tenderness; there’s no room for the vulnerability Mont and Jimmy allow themselves. The dichotomies between those two incompatible types of masculinity are essentially the same as the ones embodied by Kevin and Chiron in Moonlight. As Kevin is more at ease with his identity and his sexuality, he’s more prone to show his vulnerabilities and his desires. Whereas Chiron, ever so slowly deconstructing the multiple layers of his armor, seems stuck. He only opens up when Kevin reaches out, not unlike Jimmie who only left the street corner by virtue of Mont’s warm and caring friendship.

Ultimately, Mont represents the liberating radical love that we also see in Jenkins’ second feature If Beale Street Could Talk. Motivated to help his best friend out of the consuming illusion of ever owning the Victorian house, he sets out to finally finish the play and uses it as a vehicle to reach out to Jimmie and convey his message. But what initially was intended to be a gentle nudge spirals into an explosive catharsis for Jimmie who shouts to Mont that “people aren’t one thing”.

Bigger Thomas in Native Son, on the other hand, doesn’t get much freedom or liberation. Even in a modern day adaption by playwright Suzan-Lori Parks and visual artist Rashid Johnson, he is still the tragic figure Richard Wright intended him to be in his controversial novel. The essence of the story, in both versions, is the very notion of entrapment. Bigger (Ashton Sanders) kills the white daughter of his white employer with the same instinct for survival fueled by fear of someone backed into a corner, much like the rat he killed in his rundown house during the opening scene. When the cops catch up with him after the murder, he’s cornered into a warehouse without exits and we see him depicted him again as he’s been throughout the story: trapped.

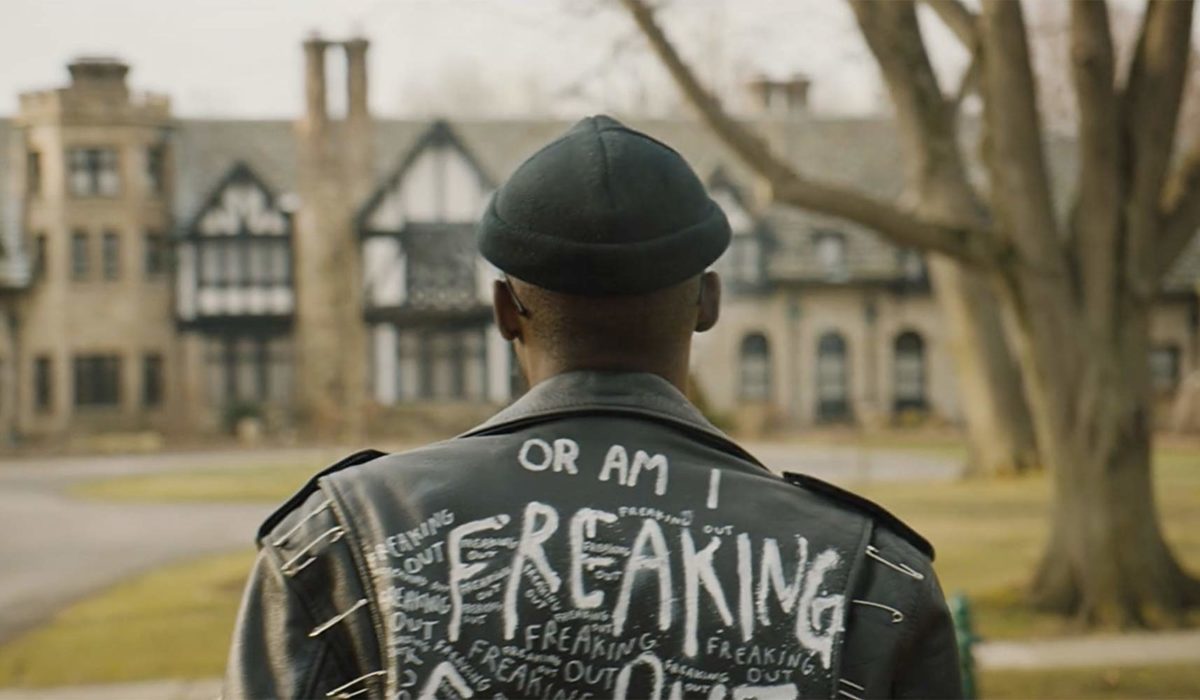

If the skateboard represented a certain freedom in Talbot’s film, a bike initially represents it in Native Son: in the film version, Bigger Thomas is a hustling bike messenger in present-day Chicago. A bird’s eye view shows him speeding down the streets of the city, wearing his studded leather jacket. That early idea of him moving and acting freely, however, quickly fades away when the bike is traded in for a car. The luxurious town car, and the fat paycheck as a live-in driver, represent a compromise, i.e. working for a white employer, Mr. Dalton, and being subject to his (and his daughters) gaze and expectations. The scene at the daunting mansion, where Bigger meets Mr. Dalton for the job interview, invokes the same disquieting dread we feel in Get Out, where entering white people’s houses feels like walking into a trap.

His so-called friend — the embodiment of the toxic male wanting to rob a neighborhood store and challenging Bigger to do it by calling him lesser than a man if he refuses — rubs salt in the open wound of Bigger’s inner struggle by concluding that he is a house-nigger for compromising. Yet, you see him relentlessly fighting against the imposed limitation to his freedom. Even physically: Ashton Sanders has managed to incorporate Bigger’s struggle in his movements with both awkwardness and elegance. Knees bent, he sort of slides and sneaks forward, ready to dodge any obstacle coming his way. Later on, as the narrative moves forward and demands a more active posture, you notice a straighter back and large, decisive strides.

Between black weirdo and black hero, Bigger expresses himself through punk-metal inspired fashion and similar musical choices. He’s resisting, or rather defying, the stereotyped expectations of blackness, up to the point that it borders assimilation, not unlike Cassius Green (Lakeith Stanfield) who looses himself using the white voice to climb up the hierarchical ladder as a call center employee in Sorry to Bother You. A brief encounter between Bigger and his extremely white-passing predecessor in the Dalton mansion feeds into that same discomforting dread mentioned earlier; the moment seems to both anticipate the horror of the tragic events to come as well as the dangers of loosing his precarious but precious identity if venturing further out on this treacherous racial divide.

Just like the sexual assault cases involving Bill Cosby add a new reading to Riggs juxtapositions in Color Adjustment, the experiences of Bigger shot through a new lens present fresh interpretations. By reiterating the literary canon and adapting Wright like Jenkins adapted Baldwin, Rashid Johnson and Suzan-Lori Parks keep the conversation flowing and the thoughts going. They opted for a lighter version of the much bleaker tragedy Wright had set out for his characters but they preserved the impossibility — or rather the difficulty — to label Bigger’s actions as right or wrong, pushing debate and reflections about structural racism forward. And since the films distribution rights have been sold in a surprising duo-deal to HBO and to A24, it will continue doing so on accessible platforms and for a broad audience.