Attending the wonderful lectures by Adrian Martin and Kelley Conway in the ‘Staging the Song’ program at Zomerfilmcollege 2016, I realized how the use of song in cinema stretches across the cinema spectrum, from the classical Hollywood tradition to far beyond; from Fritz Lang’s You and Me (1938) to Akerman’s Les rendez-vous d’Anna (1978) to Crazy Ex-Girlfriend (2015 – ). It was not only a journey through the musical form but also a journey across the world, to different countries and cultural traditions. Why are song and music so ubiquitous in cinema? Perhaps because they are such an essential part of the human experience? I for one am always whistling a musical tune when I’m happy. Song in its most utopian form is a way of connecting, a way of sharing the abundance of emotions our lives hold. In my observations on One from the Heart (Francis Ford Coppola, 1981) and Golden Eighties (Chantal Akerman, 1986) I have written about how this utopian sensibility is undermined and subverted. Let us look now at an example that reaffirms those values, perhaps one of the most lyrical musical ever (no, I am not talking about Singin’ in the Rain): Rouben Mamoulian’s Love me Tonight (1932). Like the musicals Minnelli would make a decade later it’s essentially a fairytale. Here too we are dealing with two situations; one real and one unreal.

The film starts within the real world. Documentary-like images show us the awakening of a Parisian street in the morning. Everyday sounds emanating from road digging, street sweeping, rug beating and knife sharpening, are played out in a very rhythmic way. Every street activity gets its own rhythm and thereby forms part of a symphony of sounds. We move through an open window into a room where Maurice Chevalier is getting dressed while singing the ‘Song of Paree’, written by legendary duo Rodgers and Hart. He then steps out on the street, greeting every passerby (everyone knows each other here).

Bonjour Dubal!

How’s my old pal?

Bonjour, Maurice!

How are you?

– How about Friday?

– Friday is my day!

– Oh, what a man!

– How are you?

– How’s your bakery?

– I need a beau.

– Where’s your husband?

– He needs the dough!

Hello, Mrs. Bendix!

How’s your appendix?

And what is more…

How are you?

Rhythm is not only present in the sounds, but also in the cutting, in the camera’s movement as it follows Chevalier, in the gestures and movements of the actors as well as in the rhyming dialogue. The film was not only pre-scored but it is also said that Mamoulian used a metronome to time the movement of the actors. The opening sequence presents us a utopia of the working class, a celebration of everyday movement. It is truly close to an audiovisual symphony where every rhythmic element has its own unique lyrical quality (contrary to for example Lang’s Metropolis which used rhythm to emphasize the mechanical qualities of the world).

As in Akerman’s Golden Eighties, there is a connection between clothing and love. Chevalier is a tailor with his own tailor shop. We are introduced to two customers. A simple neighborhood man who needs a suit because he is getting married, and the eminent Vicomte de Varese. For the working class man the suit is a luxury item that he can only afford for a special occasion. Chevalier has made one especially for him, but all the other suits in his shop are reserved for the Vicomte whom we see enter the shop wearing nothing but his underwear after a tumultuous night on the town. For the working class man, the suit and the love it represents are both something unique and important, but the Vicomte changes suits as fast as he changes lovers, without ever having to pay for any of it (he even borrows money from the naive Chevalier). While the pompous nobleman is being ridiculed and portrayed as irresponsible, the humble groom gets the most lyrical song of the film. ‘Isn’t It Romantic’ sings Chevalier as he fancies himself some sort of cupid (“my needle punctuates the rhythm of romance”). Much has already been said of the mise-en-scene of this song, how it moves the narrative further instead of stopping the action. (The assertion that Meet me in St. Louis (1944) was one of the first musicals to integrate songs in the narrative is thus incorrect.) Movement is key as the song passes from character to character: from Chevalier to the groom as they walk out the door to the rhythm of the song; from the groom to a cabdriver giving a poet a ride to the train station; from the poet to the soldiers with him on the train; from the soldiers to a gypsy who walks alongside them in the fields. The melody finally reaches the princess, standing at the balcony of her castle. The song – sung mostly by ordinary men except for the princess – expresses love for their occupations: once again a celebration of the everyday. They are enchanted by their own work, highlighting Mamoulian’s socialist politics (also evident in his other work like Applause or The Mark of Zorro). The song also connects the two worlds: the real one of the working class man and the unreal one, the fairytale world of the princess, the world of the nobility. She is also identified by her occupation, for isn’t it the job of a princess to be on the lookout for her prince Charming? But as her reprise of ‘Isn’t It Romantic’ makes clear, she’s still looking. While the working class celebrates the things it does have (the abundance of joy), the princess sings of something she doesn’t have yet (a lack of joy).

As if her prayers have been heard, a ladder is set against the balcony and a man climbs towards her with a rose between his teeth. The gestures and words of love are brought forth, but they lack any magical power. The man is old, as are all the men in this fairytale setting. The nobility is a dying breed, about to become extinct.

Princess: Count, why the ladder?

Count: Oh, it’s more romantic. I’ve brought along my flute, hoping to entertain.

Princess: No Count, not tonight.

Count: Oh, before I go. Remember what I said to you down by the horse though?

Princess: Quite well.

Count: What was it? I simply wish to see if it made any impression.

Princess: You said “I love you”. Made no impression whatever.

Count: There is probably no use of repeating the sentiment at this time.

Princess: None at all.

Count: Oh Princess, I trust you don’t find my wooing too ardent.

Princess: I was just admiring your restraint. Good night, Count.

Count: On with the dreams, Princess.

He leans back and accidentally falls down the ladder.

Count: I’ll never be able to use it again!

Princess: Oh Count, did you break your leg?

Count: No, I fell flat on my flute!

Surely that last bit of dialogue hints at impotence. Characters use words as if it is a game or some crossword puzzle. The one who finds the most elegant way of saying things, whose gestures seems the most effortless, wins the woman’s heart.

In classical Hollywood cinema, sometimes we, the viewers, are given opportunities to participate in the game of love. Take for instance the opening scene of Ernst Lubitsch’ The Love Parade (1929), a musical made three years before Love me Tonight and the first pairing of Maurice Chevalier and Jeanette MacDonald.

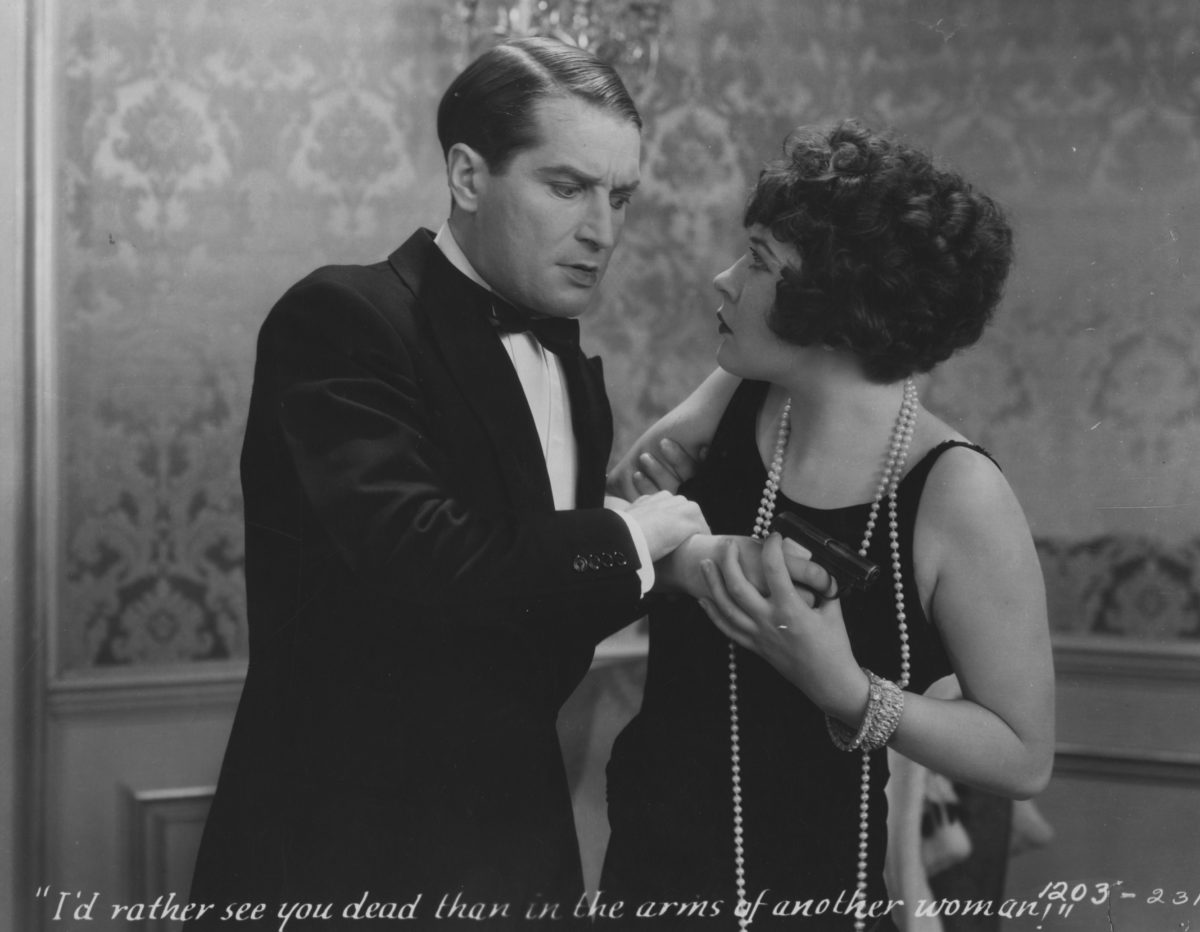

A room is shown. A servant sings a song expressing the joy of dressing the table while doing so. He exits through the door on the left. On the other side of the room there is another door. Coming from behind this closed door we hear a heated argument between a man and a woman. We are not supposed to be able to understand what they say because they speak French. Suddenly the door opens and Maurice Chevalier steps into the frame. He looks directly into the camera and explains that the woman he was arguing with is very jealous, at which point she also enters the room. She shows him a girdle and then lifts her dress to show her girdles are still there, implying that the object she found must belong to another woman. She takes a gun from her handbag and points it at Chevalier. They struggle for the gun, only to be interrupted by someone trying to force the door. It’s the woman’s husband, as Chevalier explains to us. The husband enters and for a frightening moment the couple and the husband stare at each other. All of a sudden the woman shoots herself. The husband runs to her, he picks up the gun, walks over to Chevalier and shoots him. Nothing happens. Chevalier pats his body, moves his shoulders and then shakes his head. They study the gun, unload it and find out it was loaded with blanks. The woman opens her eyes. The husband runs towards her, happy she is still alive. Chevalier smiles as he puts the pistol in a drawer filled with other fake pistols. The husband is struggling trying to button up the woman’s dress while he angrily stares at Chevalier, who in reply winks at him. The woman gets impatient and walks over to Chevalier who buttons up her dress in one elegant small gesture. He smiles at the couple while they leave the room arguing.

In these old classical Hollywood films there is always something behind the image; behind these loaded objects (the door, the gun, the girdle, the dress) and gestures. They provide us with openings in the film and allow us to complete the image ourselves.

Perhaps more explicitly than in other films the opening scene of The Love Parade initiates us in the rules of the game (or the rituals of love) when Chevalier talks directly to the audience. A tradition carried over from the theatre that subsequently grew out of fashion, but was reintroduced in the sixties by the French Nouvelle Vague.

It is truly insane how fast, elegant and effortless these shifts in relations between these three characters are played out, in only two minutes. How cleverly Chevalier’s character and the woman know how to turn this compromising situation around. The film is very much about roleplaying as he marries a Queen but has to remain in the subservient role of husband of the queen. When he courts her, the Queen teasingly asks him how she should punish him for his impudent behavior. Meanwhile the royal staff and servants are peeping through the window. Fifty shades of Grey is very tame compared to the sexual politics of this film! But things get less playful as his male anxiety grows and with it the relationship goes sour. In the last part the film is not a comedy at all but rather a sharp and dark study in human relationships. Fortunately for the (male) viewer a (false) exit is provided, the happy ending. The roles are switched and the subservient position of the woman is re-affirmed. They are happy again with each other and the curtains of their bedroom window are closed.

There are still many similarities between these early classical musicals and a film like Golden Eighties, which is also a film about the flirtation game and one that emphasizes the choreography of movement, even though the utopic ideal is lost. In Sylvie’s letters, nothing is hidden that we haven’t already seen or heard. It becomes a disposable object folded into a paper plane that eventually finds it way to the ground. Objects have become superficial and hold no value anymore. The same goes for the romantic gestures that hold no magic for the young ones and aren’t sufficient anymore for the older generation.

In One from the Heart the characters don’t even know anymore how to perform the gestures of love. I still can’t figure out what’s worse. In the days of old classical Hollywood the world is a stage, but the stage is also a world, a harmonious world. In the postmodernist world of Golden Eighties and One from the Heart the stage is a stage. The depth in the image or the illusion of depth has long been gone, a lost art.