“For I shall be the first, if I live, to bring the muse into my country.” — Virgil, Georgics.

It was in and around Manchester, England, where the “frock-coated Communist” Friedrich Engels conducted his seminal study of the working-class in 1844. He remarked: “Only in England can the proletariat be studied in all its relations and from all sides.” Quite right he was. For England, and the United Kingdom she belongs to, is forged in the fire of class conflict, where aristocracy is most acute and European socialism found its voice. So when we talk about UK cinema, it’s no surprise that a country obsessed by class excels in depicting a tale of two nations. There are prestige pictures that emphasise heritage, monarchy, and the dynastic gallivanting of the land-owning class, commonly known as “costume drama”, and there are social realist pictures designed to emphasise the hardships of the labour class, historically referred to as “kitchen sink drama”. Taken together, the contrasting aesthetic prerogatives appear to reflect a cultural output of opposing class interests—the former designed to solidify and romanticise the lifestyle of the upper-classes and the latter to lift up the disempowered lumpenproletariat. At least, that’s how it’s often framed in academic and journalist circles.

But the truth is that these genres are enjoyed conspicuously across social class. More than that, they’re more likely to be enjoyed by members of the class not depicted. Let’s just say that Ken Loach will always be more popular on the beaches of Cannes than the streets of Newcastle, for example. Likewise, the aristocracy don’t jump on the sofa to catch the latest instalment of Downton Abbey (2010-2015). This imaginary class conflict exists based on a premise, inspired by an assumption, that films do and should perform social work. If you’re the sort of person who believes that films maintain the interest of the “hegemony” by instilling within unsuspecting viewers a “false consciousness” that goes against their interest—an extremely popular view amongst the tastemakers and critical commentariat—it’s natural you’d think that films have, at their core, an ideological function. Perhaps they do. But if so, we should acknowledge the limitations of this and accept that an opulent costume drama is about as likely to perform a brain-washing function as a gritty streetside docudrama is to loosen the chains of the proletariat.

Let’s be frank: cinema isn’t that important. We cinephiles tend to validate the usefulness of our hobby in the belief that cinema will either be at the vanguard of the progressive revolution or, on the opposite spectrum, serve the propagandistic needs of the power structure, or some emergent Fascist state. From this perspective, the job—no, the responsibility!—of the critic is to perform the crucially important task of cultural seismologist, trained to detect the underlying threats and, through passive aggressive prose, monitor and hopefully nudge the art in a favourable direction. But what is cinema responsible for, really? For better or worse, about the only thing we can hold it accountable for are the temporary to long-lasting impressions reported to us by the anecdotes of individuals. That’s it. At its best, cinema reflects our experiences back to us, crystallises them as a sense-making tool, but it’s a slippery medium that evades all attempts to fanciful grand theory or being, as the hack nomenclature goes, “Explained!”.

Cinema’s sinew as an art comes from a uselessness which permits irresponsibility, and therefore liberates us from the oppressive demands of usefulness and productivity. Indeed, today à la mode “socially aware” feature films seem only to conclude on a dispiriting command to “get involved”, “do something”, or quite literally “visit this website”. When almost every decision in life, however menial, is impregnated with stupendous political significance and socially-conscious responsibility, these utilitarian instructions are surely destined to fall on deaf ears to the zero-hours labourer coming home and looking to put their feet up to a motion picture show. At the time of writing this, two of the most popular films on Netflix are Mission Impossible – Fallout (Christopher McQuarrie, 2018) and The Equalizer 2 (Antoine Fuqua, 2018). Is this evidence of a false consciousness? Or are the damned mass showing great taste in their appreciation of two of Hollywood’s most dependable populist movie stars? I know on which side I fall, and I continue to doubt that we are only one or two depictions of urban despair away from political liberation. And that’s fine. Speaking for myself, I’m happy with my useless and irresponsible hobby, and regard one of art’s finest attributes to be the excitation of the senses and the elicitation of pleasure. In many ways, the UK is a pleasure-averse nation, and our national cinema reflects it by being defined almost entirely by social relations and abstract conceptions of who or what people are and what is considered a “worthy” subject for art-making. So who, in this country, do we turn to for the noble service of uselessness? Who is it who embodies the root word of ‘art’ that means ‘skill’? Tom Cruise has skill, and so does Denzel, but who in England?

He comes from Birmingham. More specifically Sutton Coldfield, a blue-collar town on the edge of the city in the Midlands. Scott Edward Adkins is the son of several generations of butchers who attended the state-funded Bishop Vesey Grammar School. He began learning martial-arts aged ten but pursued it with extra rigour when, at 13 years-old, he got mugged on the streets. Inspired by American popular culture, he soon set his sights on action hero status. Adkins has since become an unlikely success story—a local lad done good, highly respected in his field as an actor martial-artist well-known for his virtuoso performances. Growing up on a diet of Jean-Claude Van Damme, Jackie Chan, and Bruce Lee movies, Adkins is a movie star who has felt, and seeks to continue, a tradition of cinematic pleasure. As such, he sits outside agitprop assumptions that favour concepts over feelings, his ambition lacking in sociological or intellectual pretension, which makes his project refreshing even as it has relegated him to the non-theatrical “direct-to-video” scene.

Yet he reigns supreme in his niche thanks to a blue-collar ethic: make a thing and make it well. More than any other English screen presence working today, Adkins believes in art as craft, as a discipline to be honed. By all evidence this is a humble man dedicated to his work, lacking all sense of grandiose self-importance that besmirches so many of his actor colleagues. I’ve seen Adkins interrupt his Q&As to ask an audience member, in his own regional accent, “Are you from the Midlands?”, or shout out to friends from home at public events. I’ve seen footage of Adkins bemoaning an inability to get “Tetley or PG Tips” on a Romanian set, and noticed that the highest compliment he can bestow on the myriad stars he’s worked with is “Down to Earth.” All of which is to say there’s something very ordinary about Scott Adkins, even as he rubs shoulders with the best on the international scene and forges a bespoke, idiosyncratic career usually reserved for American, Asian, or Indian stars. And that’s because there’s something extra-ordinary about him too, evident in his superlative talent and dedication as an action performer in films such as Undisputed II: Last Man Standing (Isaac Florentine, 2006), Universal Soldier: Day of Reckoning (John Hyams, 2012), Ninja: Shadow of a Tear (Isaac Florentine, 2013), Hard Target 2 (Roel Reiné, 2016), Triple Threat (Jesse V. Johnson, 2019), and Avengement (ibid., 2019) to name but a few. In these films, Adkins manages, through what appears to be sheer force of Apollonian will, to transcend the limited budgets and truncated shooting schedules offered him and often besting that coming out of a well-resourced Hollywood. Adkins personifies the archetypal action hero as the underdog who overcomes, both on-screen and in the industry, something that only increases loyalty amongst his passionate fanbase. To his followers and advocates, seen in the pages of websites like The Action Elite and Budomate, and the pages of a book like Life of Action by Mike Fury, Adkins remains a beautiful secret, even while they campaign for his talents to be more widely known.

Adkins got his first acting gig while teaching kickboxing in Milton Keynes. Noticing his talent, a producer father of some students offered him a spot on the local TV soap opera, City Central, which aired on BBC One between 1998-2000. In his very first on-screen appearance, like Athena from Zeus’ forehead, Adkins bursts onto the scene performing an inchoate, and somewhat bizarre, version of what his fans have come to appreciate him for: leaping and kicking his way out of a spot of bother. Only it’s not exotic Hong Kong or Los Angeles. Rather, he’s a track-suited felon slipping the Lancashire constabulary in what looks like, based on my local knowledge, the Arndale Shopping Centre in Manchester. From here, Adkins would appear in a roster of the UK’s most popular TV soaps, usually in a heartthrob role, including EastEnders (in which he plays a shirtless bartender), Holby City, Hollyoaks, Doctors, and Mile High—innovative serial stories about the everyday lives of the British working-class. Soap operas are a British pastime, and a reliable way for working-class actors to secure employment—long-term enough that an actor’s death by natural causes seeps into the fictional storytelling. Episodes of these programmes typically run five to six days a week in an intense production-line system that makes each actor no stranger to hard-work. With his regional accent and everyman charisma, these gigs came natural to Adkins, but from thousands of candidates only a handful of soap actors have managed to break into the big leagues, such as Ben Kingsley, James McAvoy, Keira Knightley, and Nathalie Emmanuel. When John Boyega got a role in the Star Wars franchise, he was told to lose his South London accent because “They don’t sound like they’re from Peckham in Star Wars.” Like in a galaxy far far away it’s hard to think of any regional-sounding English kung fu stars. You can make a case for Gary Daniels, but his career has never really taken off. Likewise, from Stockport, Darren Shavali’s promising talent, as seen in Ip Man 2 (Wilson Yip, 2010), was cut unfortunately short due to premature death.

Adkins seems to be aware of these hindrances, joking to journalists “Scott isn’t the best name for an action hero”, and, in another instance, bemoaning, with characteristic and humorous honesty, “These Hollywood executives—they always ignore me. I couldn’t even get on the poster for The Expendables 2. What the ‘ell was that about?” It’s telling that his breakout role, which he remains most known for, was performed in a Russian accent. In a DVD sequel to an otherwise unremarkable Walter Hill movie about prison brawling, Undisputed II: Last Man Standing, shot in Vratsa Prison in Bulgaria, allowed Adkins to rejuvenate the franchise through the hot-headed, monosyllabic Yuri Boyka, the imprisoned MMA fighter taking on an American heavyweight champion played by Michael Jai White. Since then, Adkins has stepped up his character-actor work, often adding a level of eccentricity to his hero roles and building characters that are far removed from himself, such as the IRA refugee Martin Tillman in Savage Dog (Jesse V. Johnson, 2017) and, most fun of all, the semi-psychotic Cain Burgess in Avengement. It’s fair to say that Adkins career trajectory has been filled with diversity of experience, acquiring small roles in blockbusters like The Bourne Ultimatum (Paul Greengrass, 2007), X-Men Origins: Wolverine (Gavin Hood, 2009), Zero Dark Thirty (Kathryn Bigelow, 2012), Doctor Strange (Scott Derrickson, 2016) and American Assassin (Michael Cuesta, 2017).

One gets the feeling that Adkins is deeply frustrated by his inability to break into the mainstream Hollywood circuit as an action star. Not so much a reflection of his talent, it’s a reflection of the times we find ourselves in: when the disciplined “hard-man” is considered retrograde, perhaps even politically incorrect, and so must play second-fiddle to sophisticate Benedict Cumberbatch CBE in a film about a mystic mage who summons CGI circles. There’s an element of class phobia in this—effete intellectual types looking down on working-class gym-goers. And, even with great titles behind him, it’s not clear that Adkins has managed to fulfil his fullest potential or, indeed, whether he has painted his masterpiece. Hollywood’s resources could go a long way towards doing that. While many Adkins fans yearn for the day he is given such a blank cheque, I have no such hankering. Firstly, in almost every instance Adkins has been criminally wasted when appearing in well-resourced projects. But secondly and more crucially, there’s something about the virtue of limitation and constraint that brings the best in him. This is a case of art theorist John Elster’s suggestion that: “The creation of a work of art can be envisaged as a two-step process: choice of constraints followed by choice within constraints.” We too often fetishise unbounded individual expression as the source of art, and we love to imagine what Andrew Sarris called “Faustian conflicts between high-minded artists and pot-bellied financiers”. Yet, while Adkins is restrained all over—by the expectations of genre, the prejudices of the industry, underfunded budgets, short shooting schedules, and straight-up physical exhaustion—his work is almost always better in the impecunious independent market. Here he can influence the action filmmaking and choreography, be freer to speak in his manner because of the restrictions imposed upon him. When Adkins achieves something in his field, it’s usually in spite of everything, and due to his motivational self-sacrificing passion for the form which, in turn, brings immense pleasure to his viewers and cultivates community.

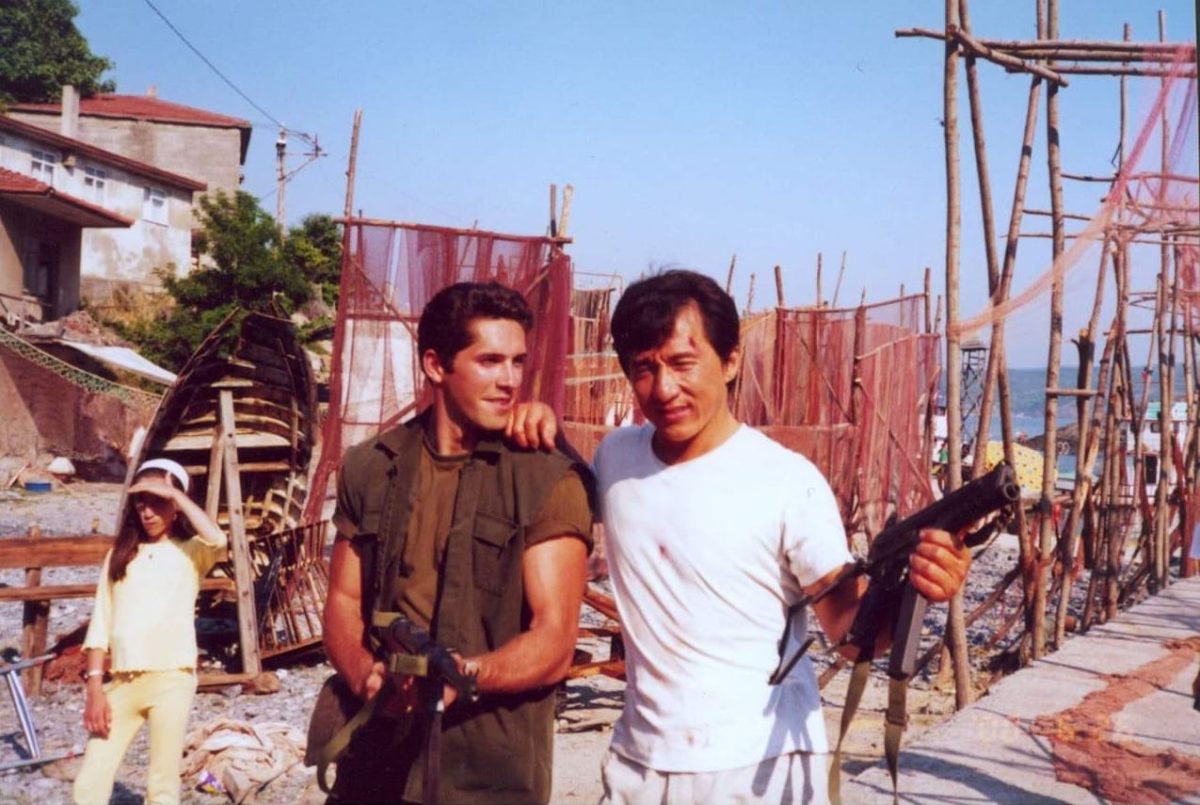

When Adkins is given more power, the action is almost always more satisfying. It makes one think he’d make the ideal action director. This is because, between his appearances on British TV, Adkins went to Hong Kong and worked under Jackie Chan and Tsui Hark, appearing in films such as The Accidental Spy (Chan, 2001) and Black Mask 2: City of Masks (Hark, 2002). The roles were minor, falling under credits like ‘Henchmen’ and ‘Bodyguard’—bad white guys, what Hong Kongers call “Gweilo”. But it gave Adkins the chance to learn action the Hong Kong way, which is one of on-the-day improvisation, complex choreography, endurance (“get used to abuse”, he describes it) and principles of on-screen movement and camera positioning that forefront the action and accentuate the physical performance. With his British everyman-ness, American imagination, and Hong Kong training, Adkins did, in many ways, uniquely shape himself into what his character Boyka describes as ‘The most complete fighter in the world’.

This became obvious almost as soon as Adkins was getting more substantial supporting roles in direct-to-video features, in large part helped by the director Isaac Florentine who knows how to shoot his favourite leading man. Following their collaboration on Special Forces (2003), in which Adkins was let loose more than any other feature prior, Florentine hired him as Boyka and, then, placed him opposite childhood hero Jean-Claude Van Damme in The Shepherd: Border Patrol (2008). Watching the film, it’s clear to see that Florentine’s camera was more attracted to the agile and energised Adkins, who’s holding back the punches in a concluding fight that has a rather dour and sad-eyed JCVD choking him out based solely on his headliner status. Adkins went on to work with Van Damme three more times, including a horribly-shot thriller called Assassination Games (Ernie Barbarash, 2011), then as his henchmen in The Expendables 2 (Simon West, 2012), and finally in Universal Soldier: Day of Reckoning , in which Adkins fully assumed the mantle as leading-man. Naturally the comparisons between the two kicking actors are easy to make, but it’s clear that Adkins always intended to break free of his hero’s shadow, which he soon began doing by taking old franchises into new directions, including with another, better Undisputed film, subtitled Redemption (Florentine, 2010), a sequel to Van Damme’s Hard Target (John Woo, 1995) called Hard Target 2 (2016), and even building his own franchise as nice-guy American ninja Casey Bowman in Ninja (Florentine, 2009) and the superior Ninja: Shadow of a Tear. Likewise, Adkins is more experimental, crossing borders as the main villain in Chinese blockbuster Wolf Warrior (2015) opposite Wu Jing and again against Donnie Yen for Ip Man 4 (Wilson Yip, 2019). He’s even appeared in Egyptian action films. What becomes clear is that Adkins, for all his experimentation, does his best work with people he collaborates with frequently, who know and see his quality. This includes Florentine, action choreographers J.J. Perry and Larnell Stovall, but also Jesse V. Johnson, the no-bullshit English director behind Savage Dog, Accident Man (2018), The Debt Collector (2018) and Triple Threat. In other words, Adkins is at his best in a trusting and well-fostered community of like-minded folk.

In recent months, as the world has gone into lockdown, Adkins has been generous to the online world by appearing in multiple interviews for GQ, Wired, and Vanity Fair, offering his professional opinion, and anecdotes, on the art of action filmmaking. As one of the industry’s hardest working men (it isn’t easy making action movies and at the frequency he does, which, in true British style, he is often complaining about), perhaps this is simply the result of Adkins trying to keep busy, but he’s also established his own show dedicated to “The Art of Action” in which he interviews his friends and colleagues about the travails and joys of action filmmaking, with guests including Tony Jaa, Michael Jai White, and Gareth Evans. Together, they form a collective of craftsmen, stunt performers, and artists all striving to add something worthy to a rich tradition which they are the inheritors of and that goes back to body-builder pioneer Eugene Sandow and the creation of cinema itself. This is a tradition they all respect and adhere to, with shared principles around the honour of physical stunt-work, minimal stunt-doubles and CGI, awareness of the canon, and reverence for the masters. Not just apparent in the direct-to-video scene, this community expands into Asian markets, where Adkins is more appreciated than at home, and in Hollywood through the go-to action design studio 87Eleven founded by John Wick (2014) directors David Leitch and Chad Stahelski, and with luminaries that include Daniel Bernhardt, Justin Wu, and Sam Hargrave, who recently took on Netflix’s Extraction (2020). It’s clear to see a continual conversation taking place between the action works—sometimes direct copying—which equates to a formal finessing in search of the next frisson.

This, it should be emphasised, is an international community and joint endeavour. In almost any other context, a film such as Triple Threat, which features a joint Indonesian, Chinese, Thai, UK and US star cast, would be praised for its representational value. But true of this community’s values, in which cultural exchange is a given and diversity is the default (they’re all martial-artists, after all), it is simply a means to an end: better work. Make no mistake: the action genre is a progressive vision of equality and cross-cultural meritocracy. It’s also pure folk-art: impassioned, ground-up expressions united under one goal, in which traditions are inherited and added to with each new generation. Adkins and his colleagues know they sit on the shoulders of giants, and he’s dedicated his career to being worthy of an ideal that can be traced to his childhood impressions. Aesthetic philosopher Friedrich Schiller said that artists are naively connected to nature in this way, and their work becomes:

“…a representation of our lost childhood, which remains eternally most dear to us […] they are representations of our highest perfection in the ideal, hence they transpose us into sublime emotion.”

In almost any interview you’ll see Adkins communicate in boyish limerence his love of craft and humbly point to the influence of the masters. I’m reminded of V.F. Perkins formulation: “To recapture the naive response of the film-fan is the first-step towards intelligent appreciation of most pictures.” At a time of generational solidarity, Adkins’ attitude to his medium’s precursors and trailblazers is one of respect, awe, and deference. Today people often take the canon as a conspiracy, forgetting that what’s elected to last is determined by artists and not ineffectual commentators. For the artist knows they are only as good as their tutor, which, in the action community, is the mall brawl in Police Story (Jackie Chan, 1985), or the Bruce Lee vs Chuck Norris fight in Way of the Dragon (Lee, 1972). This has been the spirit of art-making for millennia, a fact getting lost in fanciful Year Zero ambitions. Inscribed on the Nobel Prize for Literature are the words: Inventas vitam iuvat excoluisse per artes, which means “and they who bettered life on Earth by their newfound mastery”. It comes from Virgil’s Aeneid, when Aeneas looks upon the spirits of his forefathers in the underworld, those who contributed to the betterment of humankind through artes et scientiae. Adkins is a modern-day Aeneas (he certainly embodies the Greek value of arete, or excellence): looking back to the spirit of those whom he follows in order to continue and excel in the task they began—betterment to the world in a small but meaningful way.

In our time of lockdown, there’s been a concerted effort to encourage people to get through, say, Tolstoy’s War and Peace, or Gibbons three volumes on The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire as a matter of self-cultivation. Without sounding too philistine, for one should never discourage anyone from reading those excellent books, perhaps if we were all watching Adkins movies, which I can attest do very little for your brand, we’d be feeling less pressured to self-improve, and less worthless or guilty when we fail to meet those expectations. The action cinema community has no qualms about not abiding by the standards of the moralistic literary intelligentsia: a good script, “character development”, and bourgeois notions of symbolic meaning or virtuous messaging. In The Intellectuals and the Masses, John Carey makes the point that developments in 20th century modernist art, and its corresponding nomenclature, were partly intended to distinguish the respectable cultural elite from the newly literate masses and their popular culture. To Adkins, art continues to work as a certain type of democratic service to the community that he himself belongs to and the culture he was empowered by, and not the individual ego. And when the ego does get involved, the community is malserved and the art suffers (of which there are many cases in the genre, with Steven Seagal being the strangest example of someone exploiting his fanbase). It’s a service that has certainly helped me during these isolationist times.

So when we talk about the career of Scott Adkins, we’re not talking about lofty concepts or self-abnegation, we’re talking about love, strength, community, grace, sacrifice, imagination, passion—an ethical tradition that John Casey would call “pagan virtue”. Adkins is a civically-minded artist, often hosting martial-arts tutorials for young people in places like Newport, but also in another respect: he’s bringing his art back home. Having developed enough cache to help develop projects, Adkins has made it a point to make UK-based action films, or at least make his characters more home-inflected. While a film like Eliminators (James Nunn, 2016) is novel for framing the action in London (a fight takes place on the Thames Cable Car) and Green Street 3: Never Back Down (James Nunn & Jesse V. Johnson, 2009), shot in Newham, has Adkins paying homage to his favourite actor Gary Oldman of The Firm (Alan Clarke, 1988), it’s with Jesse V. Johnson that this patriotic ambition has picked up pace. In The Debt Collector Adkins plays a smart-mouthed English kung fu teacher struggling in LA (autobiographical?), and in Accident Man we really see Adkins’ vision come to life. Co-written and produced by the star, it’s set in a world of kung fu, underground assassins, and cockney witticism, a strange melange that’s both riotous and charming. Avengement, however, may be the pinnacle achievement (is this his masterpiece?)—as English as it gets, set almost entirely in a dingy Dagenham pub, and yet excelling as a kung fu comedy brawl picture. Representing Adkins’ working-class roots, it recalls prison films like Scum (Alan Clarke, 1979), but also his early soap work. For example, Adkins stars opposite Craig Fairbrass, who has likewise cultivated a career in the direct-to-video action market. However, to many, he still remains known for his appearances in EastEnders. When Fairbrass delivers dialogue beside a bust of Queen Victoria, a famous prop from the soap that gives the local pub “The Vic” its name, it’s hard not to see it as a highly specific reference known chiefly amongst working-class Brits. But Avengement has also got gung-ho American bravado, sardonic British humour, and award-winning Hong Kong choreography. It’s supreme populist entertainment and it comes as no surprise to know that this is Adkins’ personal favourite film, for it expresses his creative mien.

When we talk about national cinema, I suppose we’re talking about a representation of the country. I nominate Mr Adkins as the best of us: an everyman who’s also a superman, representing his country as a hard-working performer operating at the highest level of the world-stage and yet keeping it close to home. Adkins’ tale is one about the empowerment possible through genuine appreciation of popular culture and cultural forebears, and a vision of cinema that sits outside the classist, browbeating, and often dour assumptions of the British cinema and its intellectual class. Neither aristocratic or social realist, Adkins is quite literally a working-class hero whose career sits outside the binary axis of what British cinema is assumed to be. It’s no less than the expression of a good-humoured, multicultural country respectful of the past but ambitious for the future—a vision of the UK, its spirit and its working-people, as I know it and Scott Adkins embodies.