The momentum of the sixties era must have endowed some of its New Wave directors with boundless energy. Half a century later they keep adding titles to their impressive filmographies. Jean-Luc Godard, Agnes Varda and Andrzej Wajda are still making films. Věra Chytilová, Alain Resnais and Miklós Jancsó, all of whom passed away in 2014, also continued working well into their eighties.These three masters of New Wave cinema left us in quick succession: Miklós Jancsó, 31 January 2014, Alain Resnais, 1 March 2014 and Věra Chytilová, 12 March 2014. Resnais’s last film Aimer, boire et chanter had its premiere three weeks before its maker died at the age of 91. One month earlier one of the leading figures of the Hungarian New Cinema, Miklós Jancsó, had left us at the age of 92. Jancsó directed his last film when he was 89. His career spans six decades, in which he realized 33 feature films, not to mention his numerous documentaries and shorts. Yet the work of the Hungarian master has largely remained under the radar, even in cinephile circles. Is it his peculiar style that is to blame? Jancsó’s films are sometimes described as cold and stylized exercises with minimalist and disturbing narratives, lacking protagonists one can engage with. Or is the reason for his obscure status to be found in his critical treatment of Hungarian history and his explicit thematization of Marxist politics? In the formation of his political thought, Jancsó was influenced by one of his compatriots, the Marxist philosopher and film buff György Lukács. Lukács believed in the social potential of cinema and was convinced that “dogmas are the archenemy of creative Marxism.”Czigany, L. (1972). Jancso Country: Miklos Jancsó and the Hungarian New Cinema. Film Quarterly, Vol. 26(1), 44-50. Cinema has to self-examine, pose questions and debate instead of offering cut-and-dried answers or corny socialist-realist happy endings. This theoretical approach is reflected in the practice of Jancsó’s open-ended films. They offer a fascinating combination of political commitment and extreme aestheticization, something Jancsó called “the middle way” and J. Hoberman aptly described as “red modernism.”Hoberman, J. (2006, September). Red Modernism. The Hungarian Master’s late-Sixties Trilogy. Retrieved from Film Comment: http://www.filmcomment.com/article/miklos-jansco All of Jancsó’s early films are embedded in Hungarian history and explicitly refer to major wars, revolutions and revolts. Red Psalm harks back to a 19th century peasant revolt. The Round-Up concerns the aftermath of the Hungarian Revolution of 1848. No less than three films refer to the Hungarian involvement in the Russian Civil War: The Red and the White (1967), Silence and Cry (1968) and Angus Dei (1971). My Way Home (1965) is situated at the end of the Second World War. The Confrontation (1969) recalls the student revolt of 1948 and its attempt to establish Marxist People’s Colleges. The Revolution of 1956 is missing from this list, probably because overtly dealing with it might have led to Russian criticism and censorship. Yet his work doesn’t require a thorough knowledge of Hungarian history or Marxism. Its appeal comes from the universality of its central themes: violence, humiliation and the abuse of power.

That Jancsó’s films have been characterized as cold or detached is understandable, given his unique style. Yet entering the universe of the Hungarian master can be a highly emotional, even devastating experience. I think a closer view of his stylistic idiosyncrasies can help to solve the paradox of this ‘cold emotionality’. Jancsó is, in Bordwell’s terms, a ‘stubborn stylist’ whose stylistic choices are consistent within each film and throughout his early oeuvre.Bordwell, D. (2007, August 11). Bergman, Antonioni, and the stubborn stylists. Retrieved from David Bordwell’s website on cinema: http://www.davidbordwell.net/blog/2007/08/11/bergman-antonioni-and-the-stubborn-stylists Here I’d like to shed some light on the mechanisms and effects of his visual style and the aesthetic and emotional delights it so generously offers. Since the auteur Jancsó uses similar stylistic features, themes, moods and motives throughout his acclaimed sixties oeuvre, the analysis of one typical scene can serve as a gateway to an understanding of early films like Cantata (1963), My Way Home, The Round-Up (1966), Silence and Cry and the later color films The Confrontation and Red Psalm (1972).For convenience sake, I will refer to My Way Home, The Round-Up, The Red and The White and Silence and Cry as ‘the tetralogy’. I will use a scene from the first Jancsó film I ever saw: The Red and The White.

First Encounter With an Intricate Style

The Soviet authorities asked Jancsó to make a film in honor of the 50th anniversary of the October Revolution. They may have had some sort of sixties version of Eisenstein’s flamboyant October in mind, but with The Red and The White Jancsó offended his patrons. Instead of presenting them with a warm-hearted tribute to Bolshevik heroes, he came up with an anti-war picture. The events take place in 1919, during the Civil War. Forces of the Workers’ and Peasants’ Red Army are fighting a fierce and chaotic battle with the anti-Bolshevik White Army. Jancsó situates the warring Hungarian and Russian Reds and the tsarist Whites in the infinite flatness of the puszta, a landscape of steppes, dunes, marches and rivers that is part of the Great Hungarian Plain. In a hospital near a river, nurses take care of wounded men according to their Hippocratic oath: “There are no Reds or Whites, only patients.” Nurse Olga is the first sign of warmth and empathy in this world of hunting and hunted men. An unexpected moment of tenderness between her and a revolutionist is interrupted by patrolling White Guards. The interaction between Olga, the rebel and several White Guards is shown in a scene that entails two long takes.

The first deep-focus long take shows the rebel’s attempt to run away along the brook (figure 1). We see him in the left-hand corner of the frame. The frontal plane shows Olga, who intently watches the guards riding away in the right-hand corner of the frame. Jancsó will regularly exploit the extremities of his preferred, widescreen format.

Notice the importance of offscreen sound: during the tracking movement to the right, we lose sight of the horsemen, but the sound of horses’ hooves returns. As such, Olga and the viewer are prepared for the reappearance of one of the White Guards (figure 2). Olga quickly decides to undress in front of him, a ploy to distract his attention and give the revolutionist a chance to escape.

In an attempt to further exploit her ploy, the naked girl runs to the river to bathe. The camera tracks to the left and picks up other guards who are searching the haystacks and riverbed for the fugitive. We see them in the foreground while in the background the distant figure of Olga reaches the treehouse near the river (figure 3). This scanning-like left/right/left tracking movement combined with the intricate staging of moving figures in the foreground and deep background is Jancsó’s stylistic signature. There is often something inconspicuous but important to behold in the distance, like the vulnerable body of Olga in the meadow at the right of the treehouse, for every guard to see.

The nurse’s diversion seems to be working: one guard’s interest shifts from the rebel to her (figure 4). The second long take – the longest in the film – starts with him eyeing Olga and asking her to turn around. As she refuses to expose herself completely, he takes his gun and orders her to swim, mockingly calling her a water sprite.

While Olga swims away, the camera tracks and pans to the right and shows – to the viewer’s surprise and disappointment – that the fugitive has been caught (figure 5). While in the case of the horses’ hooves offscreen sound was used realistically, in this instance the unlikely absence of offscreen sound, such as screams or gunfire during the arrest, has manipulated us into hoping that Olga’s short-time lover might have escaped. We suddenly realize that her self-inflicted humiliation was in vain.

Following the guards’ order to the rebel to pull Olga out of the river, Jancsó again uses left/right/left tracking and panning as a tool to continuously restage the positions of the five characters in such a way that they are always clearly visible (figure 6). In the foreground the two guards in gaudy uniforms contrast with the barechested rebel who is forced to sing, a recurring tactic of humiliation. In the background two steady figures catch our attention: a motionless guard pointing his gun and the frail nurse, her head slightly bowed. In a moment another guard will stand next to her, order his prisoner to jump into the river and finish him off with an oar. Olga collapses and squats on the wooden pier. The three guards exit the frame on the right.

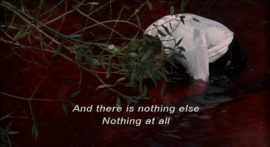

The last five seconds of this sustained long take show the tiny body of Olga (figure 7). We don’t see her face, but we realize she feels devastated. Instead of a heartbreaking scream we hear the whistling of birds, nature’s indifferent presence. Jancsó’s characters either have no emotions to show or they can’t express them. Either they don’t feel anything or they feel too much.

Jancsó’s style in his early period after Cantata is so consistent that these two long takes offer a fairly exhaustive list of themes, moods, motives and stylistic devices: the violent game of dispassionate oppressors and resigned victims, the distancing or hiding of the violent event, emotional minimalism, the manipulative use of offscreen space (which leads to a particular mood), fluid long takes with mobile framing and careful (re)staging of the figures and finally, the portrayal of a ‘morality of violence’ and the mise-en-scène of humiliation.

Rules of the Game of Violence

The opening shots or early scenes in My Way Home, The Round-Up, The Red and The White and Silence and Cry are strikingly similar. They acquaint us with the way in which violence operates in Jancsó’s universe and how he handles the viewer’s response to it. War and violence are absent in Cantata, but My Way Home, Jancsó’s third feature film, gives a first impression of the gruesome behavior of men at war. A young man tries to hide from Cossacks on horseback. He succeeds, but stumbles into three armed rebels. While they search him, we notice in the background that the horsemen have returned. The rebels are captured and brought to an ominous place, a quarry that looks like a vast arena without the cheering crowds. The three of them, together with the hapless boy, are lined up and ordered to undress. When an officer realizes the boy is Hungarian, he is set free. In the next shot only an officer and the boy are shown, but we hear the offscreen sound of three machine gun salvos: the rebels have been executed without further ado. While the line-up may have suggested that their deaths were imminent, the heedless way in which the execution is performed came as an utter surprise to me. The awkwardness of the situation is emphasized by the total lack of emotional reaction on the part of the officer and, disconcertingly, even on the part of the boy. The dead bodies of the rebels are never shown. The only dialogue their deaths evokes is chilly in its conciseness: “Done? Done.”

An early scene in Jancsó’s next film, The Round-Up, resembles the quarry scene in its unpredictability, but goes beyond it. A prisoner, accused of smuggling rebel leader Kossuth’s papers, is told he is free to go. He quickly walks away from the interrogation house, into the vast space promising freedom. His fast forward movement is emphasized by the backward tracking of the camera, then boldly stopped to a halt by a single gunshot. Again, the executioner and the sound of gunfire are located offscreen and the scene is devoid of emotion cues. In this instance, the death of the executed detainee doesn’t evoke any dialogue at all. He is immediately forgotten.

In her article ‘The Horizontal Man’, Sight and Sound critic Penelope Houston describes an analogous scene in Silence and Cry: a friendly officer asks his prisoner to get a twig from a tree up a sand dune and then urges his colleague to shoot him in the back.”Unmistakably, we are in Jancsó country,” Houston observes.Houston, P. (1969). The Horizontal Man. Sight and Sound, 38(3), 116-120. From the outset, these three introductory scenes indicate that we enter a violent universe with an internal logic that seems to be stripped of empathy and emotion. Every friendly gesture or kind invitation may result in freedom or in sudden death. There is no way to tell. Once the viewer gets the knack of this perfid system, she experiences every interaction as a potential minefield – just like the prisoners do. These introductory scenes enable Jancsó to evoke in victims and viewers alike a nearly permanent mood of apprehension and vigilance, interrupted with fierce emotional reactions caused by bursts of indifferent violence. Jancsó succeeds in creating this mood through emotional minimalism and ‘strategies of surprise’ that entail uncommunicativeness regarding offscreen space combined with the manipulative use of the long take.

Emotional Minimalism

While Eisenstein – another director with a penchant for revolutionary films – focused his art on the depiction of “aggressive moments” and the evocation of emotional shock, Jancsó prefers subdued moments and focuses on the careful construction of a particular mood. In his inspiring book Film Structure and the Emotion System, Greg Smith investigates the differences between mood and emotion. Primary emotions like fear, anger or surprise are brief states, whereas mood is a less intense but long-lasting state. A movie contains a number of emotional bursts that have a profound impact on the viewer. Yet mood is the primary emotive effect: it’s an orienting state that is usually established in the first scenes and predisposes the viewer towards experiencing intensely emotional moments. The mood is sustained during the film by reusing emotion cues (e.g. a captivating leitmotif, a gloomy set design, a specific camera movement or acting style), which prepare for and lead to the next emotional discharge. Classical Hollywood cinema tends to provide the viewer with redundant emotive cues. We not only see the chased protagonist scream in big close-ups, but the expressive lighting and suspenseful soundtrack emphasize his fear.Smith, G. M. (2003). Film Structure and the Emotion System. Cambridge University Press. Like Bresson, Jancsó is an extreme example of the opposite approach: he tempers or hides emotion cues and strives for emotional minimalism.

Blank Faces

What would Jean Epstein think of a Jancsó film? He would probably enjoy the roving camera and the minimal story line, but might regret the lack of psychologizing and the scarcity of close-ups or other emotive cues. For the French impressionist the grossissement was the soul of cinema, a direct road to photogénie. In the beginning of his career, Jancsó had no qualms about using expressive or even shocking close-ups, as the in-your-face operation sequence in Cantata demonstrates. The film tells the story of Ambrus, a young, initially somewhat arrogant surgeon who assist a genius but retired specialist during the heart surgery of a young woman. Ambrus believes the professor is too old to perform such a risky operation. During the procedure, we see close-ups of Ambrus’s concerned look and of the professor’s able hands, with gloves, without gloves, while being disinfected or palpating the throbbing heart of the woman – Bresson’s representation of the dexterous hands of ‘pickpocket’ Michel in the eponymous film came to my mind. The shots are edited with images of a heart monitor that dramatically visualize the heart rate of the patient, introducing suspense to the scene. Editing as an emotion elicitor will completely disappear in Jancsó’s next films. He has acknowledged that Cantata was influenced by Antonioni’s La Notte. Its style and narrative structure is indeed quite different from his later work. Yet, despite the presence of classical emotional sequences, the germs of his later stylistic idiosyncrasies are already present. Therefore, I feel Cantata is certainly more than, pace András Bálint Kovács, an “Antonioni replica.”Kovács, A. B. (2007). Screening Modernism. European Art Cinema, 1950-1980. The University of Chicago Press. During the operation, there are two inserts of big close-ups of the professor’s glasses and eyes. However, it is hard to decide exactly which emotion he expresses, since the inserts are stills. After the surgery the face of the exhausted professor is shown from a high angle and partly hidden behind his hand, which makes it difficult to see and interpret. In the second part of Cantata, a melancholic Ambrus leaves Budapest to visit his father in the countryside. Here, we make acquaintance with Jancsó’s fondness of white farmhouses with a courtyard in the middle of nowhere, vast open spaces, long shots and semiabstract geometrical compositions. Jancsó’s use of long shots and deep space is more prominent in his next film, My Way Home, and develops further in his ensuing masterworks. In these films emotive cues like close-ups of the human face or wild gesticulations all but disappear. Long shots with figures lingering in the background make it hard to discern facial expressions. But even if characters are clearly visible in medium shots or medium close-ups, their expression is almost always blank, irrespective of the circumstances and even of their personalities. Not only the cold-blooded characters – like most of the military men – have poker faces, but the detainees and abused women as well, the difference being that in their case emotions are expressed with other stylistic means.

Nameless Peasants

Jancsó not only avoids close-ups and intense facial gestures, but minimizes several other emotion cues as well. Many of his films lack goal oriented protagonists the viewer can engage with. The revolutionary in The Red and The White is introduced in the beginning of the film as one of the prisoners who successfully escapes a sardonic execution game, but halfway through the movie he is unheroically killed with an oar. For a while, nurse Olga seems to become the center of our emotional interest, but when the Reds overtake the hospital she too faces sudden, offscreen death. Jancsó country is too violent for protagonists to live long enough for comfortable viewer engagement. The first potential protagonist in The Round-Up is executed after less than nine minutes. When the narration shifts attention to another prisoner, he turns out to be an unsympathetic, cold-blooded murderer. Later films like The Confrontation and Red Psalm feature Eisensteinian mass protagonists with limited psychological appeal: they merely represent social classes, like the peasant, landowner, military or clergyman. Images of dancing and singing men and women dominate those of individual characters, although there is some kind of hierarchy: in Red Psalm one woman recurs regularly, even survives the bloodbath of the Whites, but remains a psychological shell typifying the oppressed peasants. Jancsó also discouraged his actors to express emotions through dialogues. Dialogues tend to be trivial or consist of repetitive military orders or incantatory rebellious slogans (“Rights for the people”) and mask rather than reveal the characters’ psyches. Jancsó’s actors often didn’t even know the names of their characters. They had a lot of leeway to improvise their lines, as long as these lines didn’t invite psychological or philosophical interpretations.

Hidden Atrocities

Although violence is a central theme, visceral violence is never shown. The viewer is not exposed to close-ups of gory battle scenes, man-to-man combat, dismembered bodies or gaping wounds. Instead, Jancsó uses three ‘masking tactics’ to represent executions or other violent confrontations: they happen offscreen (usually accompanied by the sound of gunfire); they are shown in the background (tiny figures collapsing) or they are blocked from view through intricate mise-en-scène tactics. I have described the first two tactics above, so here I will focus on the third. An example of this blocking tactic comes in The Red and The White. The Whites have a code that prohibits the assault of civilians. A Cossack who has sexually humiliated a peasant woman is ordered to give up his sword and belt, a ritual that turns out to be a preparation for his execution under martial law. Jancsó could have given us a clear view of his death, but his dropping body is partly hidden by the bodies of his executioners. We only see the dying Cossack for a fraction of a second at the bottom right of the frame.

In Silence and Cry an officer slaps a woman in the face for no apparent reason. His thrashing of a defenseless victim is blocked from view by the white wall of a farmhouse. Again, sound – the muffled screams of the victim – is the most accessible emotive cue. The continuously moving camera hides the violent event even more: next to the wall, a tree becomes a second blocking device, while the bullying officer transforms into an out of focus smear near the edge of the frame.

In Red Psalm Jancsó stretches his masking tactics to further extremes. Peasants are united in their fight against exploiting landowners, but a bailiff admonishes them for crimes against the wellbeing of the powers that be. He orders soldiers to set fire to their harvest, a pile of grain sacks. Peasant women try to convince the “cowards” of the error of their ways and ask them to throw away their guns. When the bailiff tries to avoid the soldiers’ retreat, he is caught by five peasants who shove a grain sack over his head. The subsequent action unfolds in no less than four planes: in the foreground the blazing fire dominates the frame. In a second plane behind the fire, seven dancing peasants pass by, arms linked. In the third plane we see how the bailiff is carried away, and in the background frame the retreating soldiers are still visible. While the camera moves to the right, the five peasants and the bailiff are blocked from view behind the fire, just like most of the dancing peasants.

The camera moves further to the right and shows that the five peasants who assaulted the bailiff have joined the dancers, forming a line of twelve. In a typical move the scanning camera returns to the left, to the right and again to the left. Meanwhile, the attentive viewer may have spotted the retreating soldiers near the horizon and an empty sack of grain behind the fire. Which begs the question: what happened to the unfortunate bailiff? The suggestion seems to be that he was tossed into the fire. If that is the case, it is chilling to realize that the peasants gladly join their comrades in joyful dancing immediately after they sent the bailiff to a horrific death. The now complete absence of emotive cues supportive of a violent scene thwart an adequate reaction: the murder itself is invisible, no screams of the bailiff are heard, there are no flames eating a burning body or emotional reactions of bystanders. The addition of opposite emotive cues – the gaiety of the revolutionary music of the Carmagnole – complicate an adequate viewer reaction even further. Some viewers might not even realize what has happened. The suspicion that the bailiff is dead may arise later, when it becomes clear that he doesn’t return. A similar scene halfway the film may nourish this suspicion. The priest who, like the bailiff, has condemned the people’s uprising, is locked up in his church. In the next scene, at night, the peasants set fire to the church and dance around it. Instead of the Carmagnole, we hear the crackling sound of fire. Are they celebrating not only their (temporary) victory over the church, but the death of the priest as well? Is this mood of gaiety and conviviality misleading? Do the peasants share with their oppressors a similar morality of violence? The extreme minimization of straightforward emotive cues and their replacement with contradictory ones may eventually evoke a highly emotional response in the viewer, once she realizes the rules of the game.

Strategies of Surprise

The panoramic vista of the puszta is vintage Jancsó. The endless grasslands with their racing horses and low-flying airplanes seem to hold the promise of freedom. Yet the limitless space grants no liberty, only the impossibility of hiding. The horses don’t offer the fugitives a way out of captivity, but a way back to their prisons. Even when the ‘bandits’ in The Round-Up are allowed to choose a horse to demonstrate their skills, this gesture only serves to identify rebel leader Sandor’s men. The puszta is a giant prison without bars.

Jancsó visualizes this vast landscape befittingly, through majestic widescreen long takes and lateral tracking shots. In doing so, he creates the impression of offering the viewer an all-embracing view of the characters and their surroundings. However, Jancsó doesn’t only minimize emotional information, but spatial information as well. Although the sweeping camera covers a lot of ground, it manipulatively withholds crucial story information that unfolds offscreen. While we and the prisoner think he has evaded the hunting horsemen, they have approached him offscreen behind his back. In this instance, the sound of horses’ hooves has been eliminated as well. But not only the oppressed are subject to the unpleasant surprises of the puszta. In The Red and The White, a White officer has taken control of the hospital where Olga works. He has ordered her to break her Hippocratic oath and identify the Red soldiers among the patients. His attention is caught by galloping, riderless horses across the river. At first, it is a bit of an enigma what this semi-surrealistic event signifies. When the pensive officer walks back from the river to the hospital, he suddenly drops dead. Unbeknownst to us and him, the Reds have overtaken the hospital from the other side.

In Jancso country, we constantly expect the worst. I experienced this especially during the extraordinary birch forest scene. A White Guard quietly selects a number of nurses. They have to line up and are ordered to step into a carriage, no explanation given. The women’s feeling of unease is expressed by the furtive looks they exchange, rather than by their facial expressions. The mask-like face of a White Guard watching them leave invites all kinds of interpretations. Does he know their fate? Will they be beaten, or raped, or maybe executed? It’s like a virtual Kuleshov effect: our fantasies of what gruesome happenings might unfold influence the way we read the guard’s face. But then we see the carriages and white horses riding into a fairylike birch forest, followed by a row of uniformed soldiers, black spots scattered between the white trees. A military band joins them with a happy tune. It turns out that the Whites want the ladies to perform a birch forest waltz. Our feeling of apprehension abates, while the soldiers take delight in this gracious spectacle, which is like a fata morgana in a war zone. When the officer ends the dance with the words “You are at liberty, madam, you may go home”, our sense of foreboding returns.

Jancsó’s emotional minimalism and strategies of surprise have a profound impact on our viewing experience. Violent events are difficult to predict and hard to interpret. The awkward dispassionateness of the characters in the face of life-threatening circumstances contributes to our confusion. This minimalist approach moreover enables Jancsó to forcefully express his view of the futility of life and triviality of death in an out of kilter world. People live, then die abruptly, literally disappearing from view like the lifeless body of the prisoner in Silence and Cry, rolling down the white dune and vanishing in an offscreen limbo, never to be seen again. Or like the affable Olga in The Red and The White, who tried to save a rebel but is executed by his comrades. They consider her a traitor for succumbing to the Whites’ threats and revealing the identities of Red patients. My reaction to this scene was one of shock and indignation, because of its utter unpredictability, injustice and universal sadness. The one person we could identify with simply and suddenly disappears, as if evaporated into thin air. The paradox of Jancsó’s films is that they invite or evoke strong emotions in the viewer by masking the emotions of the characters and hiding well-chosen parts of the space in which they move. His films are definitely not “coldly intellectual” or “not involved”, as Czigany would have it.Czigany, L. (1972). Jancso Country: Miklos Jancsó and the Hungarian New Cinema. Film Quarterly, Vol. 26(1), 44-50.

Posture, Figure Movement and Color

Jancsó substitutes classical ways of expressing emotions with more personal solutions. Characters who are frightened, frustrated or angry express themselves in subdued ways through the posture, position or movement of their bodies. I think of the bowed head and crouched position of Olga in The Red and The White, shocked by the rebel’s blunt execution (figures 6 and 7) or the similar posture of the deserter in The Round-Up,when he kneels in a river of blood (figure 14). Already in Cantata, emotions are expressed through the movement of the characters. When Ambrus realizes that his aging father will not join him to live in the city, the distance between them literally widens while he walks aimlessly to and fro in the open space of the courtyard.

When Jancsó started to use color film, he explored color’s potential to express emotion. It is not unusual for filmmakers to focus on the color red, because of its capacity to direct viewers’ attention. In Jancsó’s case red is an even more attractive choice, because its symbolic meanings fit his central themes of socialism and violence neatly. Indeed, the color red is regularly used in stylized and expressive ways. The most touching example comes after the massacre of the group of dancing peasants. A cadet who has deserted the army walks to the river and notices that the water is turning red. He bows forward while putting his hands on his knees, kneels down and puts his hands in the water. By now, the river surrounding him is crimson red. The cadet’s bare hands and his white shirt assimilate this color of death. His head becomes invisible, hidden behind a green-leafed branch. Loyal to his stylistic preferences, Jancsó hides facial expression to the benefit of body posture and color expressiveness. The man’s posture is reminiscent of Olga’s, after the rebel’s respectless execution.

Yet Jancsó’s alternative emotive cues are enhanced by the diegetic music performed by a guitarist who sings a mournful song to commemorate his murdered comrades. In his political-didactic color films, music is more dominant as compared to the relative silent black and white films. The combination of personal and classical stylistic elements results in a baffling scene, very involved indeed and ambiguous enough to raise the question: what exactly does the deserter feel? Does he feel guilty by proxy for the atrocities committed by his fellow-officers? Is he overcome by a universal, despairing sadness engendered by the incurable cruelty of man? Does his kneeling gesture express his solidarity with the oppressed? Or all of the above? The red river is a stylized and symbolic representation. The massacre took place in an open field without a river in sight. In Red Psalm Jancsó refuses to apply the potential of the color red for the display of realistic, gory violence. When an officer shoots a woman, her wound is shown as a bloody but painless hole in her hand, which in a next scene transforms into a red cockade. Its significance is more symbolic than emotional, as the aestheticized wound refers to Christ’s stigmata and the fascinating marriage of socialism and Catholicism. The cockade, a rosette-like emblem, refers to the French Revolution, and the peasants wearing this emblem sing socialist psalms, well-nigh forgotten texts that were found by Jancsó’s scriptwriter Gyula Hernádi.Petrie, G. (1998). Red Psalm. Még kér a nép. Flicks Books, 3.

Another impressive emotional use of color is reserved for the last sequence of the film. If there is a protagonist in Red Psalm, this label should go to the blue-dressed woman the bailiff considered to be the leader of the peasants. She recurs regularly, survives the massacre and in the end reveals herself as an avenging angel, trading her blue robe for a vindictive red dress. Her bright red garment contrasts with the dark attire of her strangely defenseless victims. These men behave like hypnotized puppets that topple over like bowling pins under the angel’s merciless volley of gunshots. In this scene, Jancsó’s use of color contrast and underexposure evokes emotions that a more classical approach could not procure.

Long Take Splendor

With his long-take aesthetics Jancsó has touched a nerve with critics, who exhaust themselves in lyrical descriptions of his graceful style. The “roaming”, “roving” camera movement is “stunning”, “convoluted” or “majestic”. Raymond Durgnat even coined the cryptical term “choreo-calligraphy”. Similar labels turn up in descriptions of the work of other long-take aficionados like Kalatozov, Tarkovsky, Tarr or Angelopoulos. But what is typical about Jancsó’s long takes? I have already pointed out their function in creating surprise and a mood of apprehension. In my analysis of the two long takes in The Red and The White, the scanning quality of the camera movement came to the fore: the camera tends to track or pan to left, lingers for a while, and then returns to or goes beyond the original position. This left/right/left-movement is usually lateral, underscores the horizontality of the puszta setting and fits with Jancsó’s predilection for the 2.35:1 widescreen format. He explored the compositional possibilities of widescreen in The Round-Up, The Red and The White, Silence and Cry and The Confrontation, for which he used Agoscope, a CinemaScope format that was developed in Sweden in 1956 and was adopted in Finland and Hungary. But Jancsó’s long-take aesthetic has more to offer.

In Silence and Cry he unleashes his stylistic creativity with beautiful long takes Béla Tarr might have cherished. The setting is again a farmhouse in the puszta, where Károly, his wife Térez, his sister Anna and his mother live. This reads like a straightforward account, but the spectator has to strain herself to determine the exact nature of the characters’ relationships. The fugitive Red soldier István is hiding with this enigmatic party of four. He has tried to escape, but as we know by now it is virtually impossible to flee the puszta. Like The Red and the White, Silence and Cry is set in the aftermath of the First World War, when the Hungarian Soviet Republic was established. After only a few months its communist leader, Béla Kun, was ousted and a period of White terror began. Kun-sympathizers like István had to run for their lives. However, this political and historical context soon shifts to the background, while a family drama unravels in the desolate farmhouse and the ‘open enclosure’ of the courtyard. In a long take of nearly five minutes, Jancsó lays the groundwork of a low-key murder plot. For this pervasively gloomy sequence, the usually freewheeling camera is pinned down to a single zone. The camera pans and tracks forward, but there is no lateral tracking. Since the camera is placed within the farmhouse, its point of view is restricted. It is capable of scanning the room and casting an eye through windows and doorways, but it can’t leave the house. In medium close-up Anna carefully adds drops of medicine to a glass of water and hands it to the old woman. We can hardly discern the old woman’s features for a number of reasons: she sits at a distance, she bows down, she is dressed in black and wears a hood, and she is backlighted and as such her face and body are underexposed. After she has sipped Anna’s glass of water, she inexplicably drops to the ground. Her already limited perceptibility diminishes further, as her collapsed body is represented as a black shape at the bottom of the frame. Later in this lengthy shot Jancsó displays a minimalist, painterly table scene of four people praying and eating. It is a fine instance of careful lateral staging, with the old and seemingly recovered woman joining the group on the right. Because of her bowed posture and the lack of contrast between her black clothes and the dark grey wall, it is as if she’s vanishing in shades of black.

To add to this dismal atmosphere, the soundtrack features diegetic farmyard sounds of chickens, dogs and birds (start worrying when you hear birds in Jancsó country). The whole scene has an abstract geometric quality, since the doorways, windows and wooden beams divide the frame in squares and triangles, used as framing devices for the characters. Only later we realize that this scene is full of signs that refer to a murder plot: Anna and Térez are not taking care of the old woman; they are poisoning her. Only when more story information seeps in, we realize how morally depraved Anna and Térez really are. In retrospect, this scene depicts a Huis Clos situation where other people are l’enfer, the characters figuratively have no exit and the camera literally can’t leave the premises. For good metaphorical reasons, Jancsó doesn’t hesitate to restrain his roving camera.

In Red Psalm the characters still move around in an unstructured space. Peasants, children, soldiers and landowners linger, run or form lines to dance or march. Racing horses crisscross the space, skillfully maneuvering between peasants, sheep and carts. The presence of dozens of characters requires a tactic to give the viewer access to such an overpopulated set. Jancsó uses a combination of long lenses, zoom shots, shallow focus and rack focus to guide viewers’ attention. His camera is as mobile as ever, but eschews long shots to the benefit of medium shots and medium close-ups of faces and folkloric objects. The long-take, long-lense tactic results in chaotic or dense compositions, because the long lense flattens the space and causes hazy foreground figures to clutter the frame. Still, Jancsó’s style brings order to the chaos by picking out points of interest – an officer, a peasant woman, a green jar, a red ribbon, a platter of food – following them for a while and shifting attention to another point of interest. Within one long take the camera temporarily follows and abandons several peasants and soldiers, a way to cinematographically express the absence of real protagonists and the importance of all the members of the different social classes. As such, he adds a ‘Marxist’ meaning to an Antonionian stylistic device and raises the bar by shifting to a new character more quickly and more often in one long take. Moreover, the extended long take in Red Psalm enables Jancsó to juxtapose these conflicting classes. While the tracking camera follows a man moving to the left, the background consecutively features the peasant-guitarist, a group of officers celebrating their victory and eventually the priests and acolytes, ringing bells and swinging censers. Every time the camera picks up a new group, the accompanying music abruptly changes to a score that fits its class.

Morality of Violence and the Mise-en-scène of Humiliation

In my analysis of Jancsó’s style and its emotional impact, his thematic interests came to the fore as well. His films deal with power imbalances on a military, social and individual level. This imbalance is usually so profound – certainly in the tetralogy – that the oppressed are completely at the mercy of their oppressors. Crucial to Jancsó’s vision of the logic of war and revolution is the idea that, once the oppressed get into power “they change and immediately try to oppress and exploit everyone else.”Petrie, G. (1998). Red Psalm. Még kér a nép. Flicks Books, 33. The Red and The White was disliked in Russia because some of the Bolsheviks were portrayed as mirror images of the merciless Whites. The peasants in Red Psalm, despite the gay atmosphere with cheerful dancing, whirling ribbons and naked girls, burn or shoot their opponents without the blink of an eye. In comparison, the revolt of the Marxist students in The Confrontation is a rather peaceful event, but it lays bare the difficulties of achieving the goal of a truly democratic leadership. At one point Jutka, the revolutionist leader, orders the burning of the books of the Catholic students. She wants to convince them of the necessity of communist People’s Colleges, oblivious of the Nazist overtones of her intervention. Jancsó’s critique of communism’s affinity with exploitation and violence resonates with Oshima’s similar exercise in self-reflection in Night and Fog in Japan (1960). In this film the Japanese director criticizes – in his own exceptional foray into long-take aesthetics – the authoritarian leadership of the Zengakuren, the communist league of Japanese students.

The violence in Jancsó country is based on an internal ethical framework in which values like patriotism and honor play a central role. In the multiple moralities approach, the ‘morality of violence’ is one of the five moral systems that people use to underpin and legitimize their moral conduct.Verplaetse distinguishes five moral systems: familial morality, morality of violence, purification morality, morality of cooperativeness and principled morality. Empathy and attachment, scarce emotions in Jancsó country, belong to familial morality. Honor and revenge are essential ingredients of the morality of violence. Verplaetse, J. (2008). Het morele instinct. Over de natuurlijke oorsprong van onze moraal. Nieuwezijds. In Silence and Cry an officer distinguishes his moral system from a ‘familial morality’ when he states: “Listen, I’d finish off my own father if I was ordered to.” In a similar vein, a peasant in Red Psalm realizes: “I know if you were ordered you would even murder your own fathers.” When war is at hand, the hierarchy of values shifts from family ties – and other moral systems, like principled morality – to honor and patriotism.

Honor is expressed in the philosophy of open warfare as opposed to trench warfare. In the concluding battle in The Red and The White, the Reds march the puszta side by side, proudly showing their camaraderie and courage in the face of an overwhelming opponent. Real men don’t hide in trenches; they boldly show themselves – and get shot. An officer in Red Psalm derides the peasants for “hiding behind their children”, for a true Hungarian is “chivalrous, open and patriotic”. Honor materializes in military uniforms, decorations, swords, plumed hats, clean shirts and polished boots. Completely dressed up, the officers look like parading peacocks. In The Round-Up, the oppressors even wear ahistoric black cloaks that seem to bestow them with Nosferatu-like malignancy. In marked contrast with this male vestimentary display, Jancsó develops the motif of the naked figure. Compulsory undressing is a recurring tactic of humiliation for both men and women. Male prisoners usually have to take off their shirts, resulting in a stark hierarchical contrast between the uniformed soldier and the barechested detainee. After a while the command to undress contributes to our apprehensive mood, because we realize it is often the harbinger of death. When women are ordered to take off their clothes, the humiliation is of a sexual nature. This difference in treatment is clearly visible in The Round-Up. Women accused of membership of rebel leader Sandor’s gang are stripped naked, while the fully dressed men suffer a humiliation of an opposite kind: they have to wear white hoods that seem to function to erase their identities and intensify their sorrow. One of the women will be subjected to a torture game, performed on the puszta stage before an unwilling audience of hooded men. When they are ordered to take off their hoods, they find themselves in the ‘royal box’ of this perverted stage play.

The men witness how their female comrade runs naked to and fro between two lines of soldiers. They whip her relentlessly until she collapses. One of the spectators – the woman may have been his lover or wife – can’t bear the sight of it and after an explicit, un-Jancsóian display of emotions commits suicide. Compared to the detached representation of violence, the mise-en-scène of humiliating nakedness is relatively explicit. Between the rows of soldiers, the whipped woman’s breasts and pubic hair are visible. In Silence and Cry a young girl is undressed and caressed by Térez, a gesture that holds the middle between humiliation and tenderness. Can we deduce that the murderous women are running a prostitution business on the side as well? Humiliation is not a prerogative of men or women, Reds or Whites; it is a tactic of whoever is in power. With the unsavory behavior of the women in Silence and Cry Jancsó already undermined the notion that questionable ethics is a strictly male territory. In The Red and The White he showed that when humiliation is in conflict with the code of honor, the humiliator himself will be humiliated and punished or executed. This tactics of humiliation stretches from 19thcentury Austria-Hungary and Nazi Germany to Abu Ghraib, where “the whole nudity thing” was “part of the military intelligence process.”Zernike, K., & Rohde, D. (2004, June 8). Forced Nudity of Iraqi Prisoners Is Seen as a Pervasive Pattern, Not Isolated Incidents. Retrieved from The New York Times on the web: http://www.nytimes.com/learning/students/pop/articles/08NAKE.html. Besides sexual humiliation, Iraqi prisoners were forced to sing ‘The Star-Spangled Banner’ and do jumping jacks. This is discouragingly similar to the obligatory singing and rabbit-jumping in Jancsó’s world. Nevertheless, Jancsó country isn’t a lawless moral wasteland, it just privileges a dubious moral system that throughout the ages has had the tendency to flourish in times of war.

Gripping ‘Anti-Cinema’

If a highly personal, stubborn style and the pre sence of recurrent themes are fundamental criteria for auteurism, Jancsó certainly qualifies. He strived for this status, distancing himself from the classical Hollywood fare, which he associated with an all too overt display of emotions, the manipulative use of realism and a hierarchical studio system that smothers creativity and “degrades fellow-artists to second-rate figures.”Bisztray, G. (1980). Auteurism in the Modern Hungarian Cinema. Canadian-American Review of Hungarian Studies, Vol. VII(2), 135-144. He found it crucial to be able to work with a team of kindred spirits for every new project. The scripts of all the films discussed here, except Cantata, were written by his friend Gyula Hernádi. The actor András Kozák plays important roles in three films of the tetralogy, despite Jancsó’s shying away from the use of real protagonists. The final image in these films supports the hypothesis that his actor-friendfunctions as his alter ego: a close-up of Kozák who looks the spectator in the eye (figures 19-21). The Japanese New Wave director Kiju Yoshida has described the films of Ozu and his own work as ‘anti-cinema’: a cinema that breaks the rules of classical montage and composition, denies the importance of an intricate storyline and “avoids the comfortable cradle of emotions.”Yoshida is unfortunately as overlooked as Jancsó, but luckily, Dick Stegewerns has edited a fine volume on Yoshida’s work, including texts of the filmmaker himself. Stegewerns, D. (2010). Master of the Modern Art Film. In D. Stegewerns, Yoshida Kiju. 50 Years of Avant-Garde Filmmaking in Postwar Japan. (pp. 5-7). Norwegian Film Institute. Yoshida, K. (2010). My Film Theory. The Logic of Self-Negation. In D. Stegewerns, Yoshida Kiju. 50 Years of Avant-Garde Filmmaking in Postwar Japan. (pp. 15-19). Norwegian Film Institute. Jancsó’s early oeuvre similarly shuns the soothing cradle of emotions, but through his method of emotional minimalism he has succeeded in creating gripping anti-cinema.